Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to compare the engagement in moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA in axSpA patients with and without current physical therapy (PT).

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, a survey, including current PT treatment (yes/no) and PA, using the ‘Short QUestionnaire to ASsess Health-enhancing PA’ (SQUASH), was sent to 458 axSpA patients from three Dutch hospitals. From the SQUASH, the proportions meeting aerobic PA recommendations (≥ 150 min/week moderate-, ≥ 75 min/week vigorous-intensity PA or equivalent combination; yes/no) were calculated. To investigate the association between PT treatment and meeting the PA recommendations, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using logistic regression models, adjusting for sex, age, health status and hospital.

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 200 patients, of whom 68%, 50% and 82% met the moderate-, vigorous- or combined-intensity PA recommendations, respectively. Ninety-nine patients (50%) had PT treatment, and those patients were more likely to meet the moderate- (OR 2.09 [95% CI 1.09–3.99]) or combined-intensity (OR 3.35 [95% CI 1.38–8.13]) PA recommendations, but not the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation (OR 1.53 [95% CI 0.80–2.93]). Aerobic exercise was executed in 19% of individual PT programs.

Conclusion

AxSpA patients with PT were more likely to meet the moderate- and combined-intensity PA recommendations, whereas there was no difference in meeting the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation. Irrespective of having PT treatment, recommendations for vigorous-intensity PA are met by only half of the patients. Implementation should thus focus on aerobic PA in patients without PT and on vigorous-intensity PA in PT programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease, with back pain and stiffness as main symptoms and encompassing both non-radiographic and radiographic axSpA (ankylosing spondylitis) [1, 2]. The literature shows that axSpA is associated with both decreased cardiorespiratory fitness [3,4,5,6] and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [7, 8], which are interrelated [9,10,11,12]. Adequately dosed aerobic physical activity (PA) according to public health recommendations improves cardiorespiratory fitness in people with axSpA [13, 14] and might reduce the cardiovascular risk. For this reason, it is advocated in international recommendations on PA in people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal conditions [15]. Aerobic PA concerns PA executed with moderate or vigorous intensity. Recent studies suggest that vigorous-intensity PA is most effective in improving cardiorespiratory fitness and reducing cardiovascular risk [10, 16,17,18] and it shows to be both beneficial and safe for people with axSpA [19, 20]. Therefore, especially vigorous-intensity PA should be pursued by people with axSpA, at least by those without an increased risk of cardiovascular complications during exercise.

This raises the question to what extent people with axSpA are actually engaged in aerobic PA, either or not with vigorous intensity. A previous study reported that evidence on PA engagement of people with axSpA is limited and heterogeneous in nature [3]. Nevertheless, it appears that the engagement in adequately dosed aerobic PA is insufficient, in particular in vigorous-intensity aerobic PA [21,22,23,24]. Three studies, all using accelerometers, showed that people with axSpA engaged less in vigorous-intensity PA than population controls, while the total amount of PA was comparable [21,22,23]. Another study found that more people with axSpA comply with the moderate-intensity PA recommendation (57%) than with the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation (32%), using a non-validated PA questionnaire [24]. That study used the PA recommendation prescribing moderate-intensity PA for ≥ 30 min on ≥ 5 days per week or vigorous-intensity PA for ≥ 20 min on ≥ 3 days. Other studies on aerobic PA in people with axSpA [3, 21, 23, 25] were based on the recommendation by the World Health Organization (WHO) [26], which does not state a required minimum frequency, but prescribes ≥ 150 min of moderate-intensity PA, ≥ 75 min of vigorous-intensity PA per week or an equivalent combination of this. It was reported that this recommendation was met by approximately half of patients [21, 23, 25], but no distinction was made between the proportions of people meeting the moderate- or vigorous-intensity PA recommendations. None of the studies distinguished between leisure time and work-related aerobic PA either, whereas leisure time PA appears to have greater health benefits [27,28,29,30,31] and is probably more easily modifiable than work-related PA. This superiority of leisure time PA could probably be caused by the difference in the nature of activities or by more opportunities to rest when desired and recover between sessions [27, 29].

Another limitation of previous studies on aerobic PA among people with axSpA, besides not distinguishing between moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA and between leisure time and work-related aerobic PA, is that none of the studies so far took the role of physical therapy (PT) into account. This is striking as relatively many axSpA patients have PT treatment [32] and it is generally acknowledged that apart from other health professionals, physical therapists play an important role in the promotion of PA [15]. However, it appears that aerobic PA may not be included in PT treatments often [32] and that the aerobic PA employed in exercise programs for people with axSpA is often inadequately dosed [20, 33,34,35].

To implement aerobic PA recommendations in people with axSpA, it is important to know what the focus of implementation activities should be, both in patients with and without PT treatment. Due to the physical limitations for which axSpA patients seek PT treatment, it is not necessarily expected that patients with PT are more inclined to meet the aerobic PA recommendations. Moreover, PT programs may not include (advice on) aerobic PA [32]. Given the lack of knowledge on the association between having PT treatment and meeting aerobic PA recommendations among people with axSpA, the aim of the present study was to compare the engagement in moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA (during work and leisure time) in axSpA patients with and without PT treatment.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional, multicenter study consisted of a once-only survey among people with axSpA living in the southwestern region of the Netherlands. In this survey, participants were asked whether they had either individual or group PT treatment, to compare PA of patients with and without any guidance from a physical therapist. In the Netherlands, PT for people with axSpA can both be offered on an individual basis or by means of axSpA-specific supervised group exercise. This group exercise usually consists of weekly land- and water based exercises supervised by a physical therapist and is organized by local patient associations for people with a rheumatic disease [34]. The study obtained ethical approval from the Leiden University Hospital Ethical committee (P14.326). The reporting of this study was done in accordance with the checklist for cross-sectional studies from the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement’.

Patients

In 2015, registers of three hospitals in the southwestern region of the Netherlands (Leiden University Medical Center in Leiden, Haga Hospital in The Hague and Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis in Delft) were screened for patients with a confirmed diagnosis of axSpA who had ever visited the rheumatology outpatient clinic. The survey was sent by postal mail to eligible patients, including an invitation letter on behalf of their treating rheumatologist, an information leaflet, an informed consent form and a pre-stamped envelope. No reminders were sent.

Assessments

The survey was self-developed and first pilot-tested by patient representatives affiliated with the Dutch Arthritis Society. It measured the following variables:

-

a.

Demographic and clinical characteristics: sex, age, year of diagnosis and use of medication related to axSpA (painkillers (acetaminophen or opioid painkillers); Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), biological Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs); synthetic DMARDs; no medication related to axSpA).

-

b.

Health status, using the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society Health Index (ASASHI), which is a valid, reliable and responsive questionnaire measuring functioning, health and disease impact in people with axSpA [36, 37]. The ASAS HI includes 17 questions and results in a score between 0 and 17, with a lower score indicating a better health status.

-

c.

PT treatment, by asking whether they had PT treatment, either at the time the study was conducted (current PT; yes/no) or ever in the past (yes/no). Moreover, it was asked whether they were or had been treated individually in a practice (yes/no) and/or in a group with axSpA-specific group exercise therapy (yes/no). Furthermore, for individual PT, the duration (> 5 years, > 3 years, > 1 year, > 6 months or < 6 months), frequency (less than weekly, weekly, twice weekly, more than twice weekly) and contents (15 treatment options) of PT treatment were recorded. These 15 treatment options were clustered according to the four groups of treatment modalities as described in the national physical therapists’ professional profile developed by the Royal Dutch Society of Physical Therapy [38]: Counseling (including education on home exercise; coping; and PA and sports); Exercise (including active joint range of motion exercises; muscle strengthening exercises; aerobic exercises; balance exercises; and relaxation exercises); Manual treatment (including passive mobilization; and massage); and Applying physical modalities (including thermotherapy; kinesiotaping; electrotherapy; ultrasound; and dry needling).

-

d.

Aerobic physical activity, using the validated Dutch version of the ‘Short QUestionnaire to ASsess Health-enhancing PA’ (SQUASH) [39, 40]. The SQUASH consists of 17 items asking respondents to recall PA as performed during a regular week in the past 12 months, yielding the time duration per PA intensity and the type of aerobic PA. The SQUASH categorizes PA into PA during commuting, (light and heavy) work, (light and heavy) household, walking, cycling, gardening, odd jobs and sports. For the purpose of this study, these categories were dichotomized into leisure time PA, including recreational walking, recreational cycling, exercise and sports, and non-leisure time PA, which includes PA during commuting, work, household, gardening and odd jobs. Using the compendium of Ainsworth [41], a research assistant (JP) assigned the correct MET-values to the corresponding activities. The SQUASH uses a syntax to categorize the activities into light-, moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA, by combining activities’ MET-values with both participants’ age and a subjective effort-score (slow, average, fast) that participants assigned to each activity. Aerobic PA includes all PA performed with at least moderate-intensity. The SQUASH data were used to calculate whether patients met the moderate- (≥ 150 min/week), vigorous- (≥ 75 min/week) and/or combined-intensity (≥ 75 min/week vigorous- and/or ≥ 150 min/week moderate- or vigorous-intensity PA) aerobic PA recommendations by the WHO [26]. This was examined both for PA during all daily activities and during leisure time specifically.

Statistical analyzes

The returned questionnaires were scanned and analyzed by Cardiff® Software (California, United States) and manually checked and corrected afterwards. Descriptive statistics were used to describe patient characteristics, the proportions meeting the aerobic PA recommendations and the engaged types of leisure time and non-leisure time aerobic PA. This was done for the total group of participants and for patients with and without PT guidance separately. Results were reported as percentages or medians with minimum (Min) and maximum (Max) values, where appropriate.

To investigate the differences in characteristics between patients with and without PT, the median test for independent samples was used for continuous data and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical data. In addition, six logistic regression models were estimated with meeting the moderate, vigorous or combined-intensity PA recommendations, both during all daily activities and during leisure time, as the dependent variables and current PT treatment (individual and/or group) as independent variable. To control for confounding, sex, age, health status and hospitals were included in the models as independent variables. All statistical analyzes were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

Patients

The questionnaire was sent to 458 axSpA patients of whom 206 returned it (response rate 45%). Six of them were excluded because the SQUASH data were either missing (n = 3) or invalid (n = 3).

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1, for the total group and for patients with and without PT separately. The majority of patients was male (69%), the median age 57 years and the median disease duration 23 years. The median ASAS HI score was 5.3, indicating moderate health status [37]. Ninety-nine patients had PT treatment at the time the study was conducted: 77 had individual PT treatment in a private practice only, 11 participated in axSpA-specific group exercise therapy only and 11 had both individual PT treatment in a private practice and group exercise therapy (on two different days). The group exercise therapy consisted of a standardized program comprising weekly land- and water based mobility and strengthening exercises and sports (mostly volleyball) in most patients [34]. Table 2 shows the duration, frequency and contents of current individual PT treatment. Among the 88 participants who were receiving individual PT at the time the study was conducted, the duration of treatment was more than five years in 66 patients (75%) and the treatment took place less than once a week in 44 patients (50%). Furthermore, the individual PT treatment included counseling in 67 (76%), exercise in 47 (53%), manual treatment in 80 (91%) and the application of physical modalities in 24 (27%). Regarding contents with a direct link to aerobic PA recommendations, education on PA and sports was reported by 37 patients (42%) and aerobic exercise during PT treatment by 17 (19%). Among the 101 participants without current PT, 84 had PT treatment ever in the past. No statistically significant differences regarding sex, age, disease duration, medication use, ASAS HI score and being employed were found between patients with and without PT.

Aerobic PA recommendations

Table 3 presents the proportions of participants meeting the aerobic PA recommendations during all daily activities and during leisure time. This table shows that for all daily PA, the moderate, vigorous- and combined-intensity PA recommendations were met by 68%, 50% and 82% of the participants, respectively. With respect to meeting the aerobic PA recommendations by taking only leisure time PA into account, the proportions of participants meeting the moderate-, vigorous- and combined-intensity PA recommendations were 48%, 42% and 67%, respectively. Moreover, 68% of the participants engaged in any moderate-intensity leisure time activities, whereas 50% of participants engaged in any vigorous-intensity leisure time activities.

PT and aerobic PA recommendations

To study the association between PT treatment and aerobic PA, only current PT treatment was considered, since almost all participants (92%) had ever had PT. The differences between patients with and without current PT regarding the meeting of aerobic PA recommendations are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 3. Table 3 shows that, considering all daily PA, patients with PT are significantly more likely to meet the moderate- (OR 2.09 [95% CI 1.09–3.99]) and combined-intensity (OR 3.35 [95% CI 1.38–8.13]) PA recommendations than patients without current PT after adjusting for sex, age, health status and hospital. When only including leisure time PA, patients with PT are more likely to meet the moderate-intensity PA recommendation (OR 1.86 [95% CI 1.03–3.36]) than patients without PT, with no differences for the vigorous- or combined-intensity PA recommendations.

Types of aerobic activities

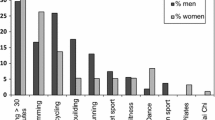

Figure 2 presents the proportions of axSpA patients with and without PT engaging weekly in different forms of leisure or non-leisure time aerobic PA. There were no statistically significant differences between the proportions of participants with and without PT engaging in the different types of aerobic activities, besides engagement in group exercise and aqua-aerobics; these types of aerobic PA were executed by significantly more patients with PT. This difference is likely to be due to participants with group PT, which often consists of group exercise and hydrotherapy in the Netherlands [34]. In both groups, it appeared that walking (69%) and cycling (57%) were the most frequently performed aerobic activities.

Discussion

This study found that people with axSpA who were having PT treatment were more likely to meet the moderate- and combined-intensity aerobic PA recommendations than those without PT, whereas there were no differences in meeting the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation. Irrespective of current PT treatment, the proportion of participants meeting the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation was relatively low and often not attained with leisure time activities.

The finding that having PT treatment was associated with meeting aerobic PA recommendations was not necessarily expected, because PT programs may not include aerobic PA and those who need PT treatment are expected to have more physical limitations and may thus be less physically active. In our study, PT treatment was related to more aerobic PA, but this did not pertain to vigorous-intensity PA. Given the cross-sectional design of the study, it remains unclear whether the association between PT and aerobic PA is a result of PT treatment or that axSpA patients who are already relatively active are more inclined to seek PT treatment. Either way, the findings show that specifically axSpA patients without PT should be better educated on the benefits of aerobic PA. It is recently recommended that all health professionals in rheumatology should promote aerobic PA [15], but especially physical therapists could play an important role in such education, in particular since most individuals with axSpA have PT treatment at some point during their disease course, as confirmed in the present study. However, there is room for improvement in those with PT as well. Our study showed that education on PA is currently only provided in 42% of axSpA patients with individual PT in the Netherlands. In addition, aerobic exercise was only executed during PT in 19% of individual PT programs. This is unfavorable, as guided practice is one of the most important intervention components to optimize exercise behavior of axSpA patients [42]. Ideally, axSpA patients could experience and practice vigorous-intensity PA under supervision of a physical therapist. Therefore, aerobic PA should be included more often in individual PT programs, in particular with vigorous intensity.

The finding that particularly vigorous-intensity PA was performed insufficiently by relatively many axSpA patients is consistent with previous findings [21,22,23,24]. Similar to patients without PT, only half of those with PT met the vigorous-intensity PA recommendation. This finding could be related to results from previous studies, showing that appropriately dosed aerobic PA is often not included in (PT) exercise programs [33, 34]. A recent study on content of PT in axSpA patients found that in the Netherlands, aerobic exercises are only performed during individual PT in 22% of patients [32]. Hence, when implementing vigorous-intensity PA among people with axSpA, barriers and facilitators of both patients and therapists should be accounted for. A cross-sectional study examining these barriers and facilitators [19] found that motivation, disease symptoms and group heterogeneity could act as both barriers and facilitators according to patients and physical therapists. An implementation strategy could include education for therapists on how to motivate patients for vigorous-intensity PA and how to tailor and adjust it to varying symptoms, individual preferences and other potential variances among individual patients, such as the presence of comorbidity.

An important note when implementing vigorous-intensity PA is that caution is needed with sedentary individuals and people with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications during exercise [17, 43, 44]. Still, for most axSpA patients, vigorous-intensity PA should ultimately be aimed for, since this appears to have more health benefits [10, 16,17,18] and is more time-efficient [45], while time is an important exercise barrier in axSpA [19, 46, 47].

Regarding the types of actual activities, about half of the participants did not engage in any vigorous-intensity PA during leisure time at all. Studies reporting on the superiority of leisure time PA suggest that possible explanations for the greater benefits of leisure time PA are the difference in nature of activities and the presence of more opportunities to rest and recover when needed [27, 29]. The observation that recreational walking and cycling were the most popular forms of aerobic PA in our study could guide physical therapists in their advice and guidance on specific activities that are likely to be maintained in daily life. It is nevertheless conceivable that preferences for recreational activities may vary not only among individuals but among countries as well.

Overall, the proportion of patients meeting the WHO PA recommendation in the current study was much higher than in previous studies, namely 82% as opposed to around 50% in previous studies [21, 23, 25]. It is conceivable that the discrepancy might be due to the use of the SQUASH questionnaire. Another recent Dutch study using the SQUASH questionnaire among the general population and people with osteoarthritis found even slightly higher proportions of participants meeting the combined-intensity PA recommendation [48]. Nevertheless, despite the probable overestimation of the amount of aerobic PA, the current results are useful to compare subgroups within a population; the SQUASH has indeed shown to be fairly valid and reliable for within group comparisons [39, 40, 49]. Therefore, the SQUASH can be regarded as a valid measure to investigate the main objective of this study; to compare moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA between axSpA patients with and without PT. This comparison appears to not have been studied before and is important information to account for when implementing the aerobic PA recommendation.

This study has a number of limitations. First, because of the cross-sectional study design, no conclusions can be drawn about any causal relationships between having PT and aerobic PA. Second, and as already addressed, using a self-report questionnaire the amount of PA might have been overestimated [49]. Another limitation of the SQUASH is that it does not measure sedentary time. Moreover, it asks participants to recall their PA during a regular week in the past twelve months, whereas the groups compared in this study are based on having PT treatment at the time the study was conducted. As 89% of participants with individual PT were treated for more than 12 months, possibly not in all patients with PT, but at least in most of them, the actual influence of PT treatment on PA have been measured. Finally, the generalizability of our study is limited because the response rate was moderate (45%) and patients were recruited from only three hospitals in one region of the Netherlands. Although the participants of this study were relatively old [3], their sex ratio [3] and the proportion with PT [50] were comparable to other studies.

In conclusion, axSpA patients with PT were more likely to meet the moderate- and combined-intensity but not the vigorous-intensity aerobic PA recommendations than those without PT. These findings imply first of all that in axSpA patients without PT, aerobic PA must be promoted. Second, as vigorous-intensity PA appears insufficiently implemented among those with PT, additional education of physical therapists regarding the importance of and requirements for vigorous-intensity exercise as an essential element of PT programs for axSpA patients seems warranted. With the education of physical therapists, it should be noted that only 19% of patients with PT reported executing aerobic exercise as part of their PT treatment. This may indicate that there is a window of opportunity for physical therapists to increase patients’ engagement with vigorous-intensity PA. Future research should thus focus on interventions to optimize aerobic PA in axSpA patients without PT and on the implementation of vigorous-intensity exercise in PT programs.

References

Sieper J, Poddubnyy D (2017) Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet (London, England) 390(10089):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4

Van Der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, Van Den Bosch F, Sepriano A, Regel A, Ciurea A, Dagfinrud H, Dougados M, Van Gaalen F, Géher P, Van Der Horst-Bruinsma I, Inman RD, Jongkees M, Kiltz U, Kvien TK, Machado PM, Marzo-Ortega H, Molto A, Navarro-Compàn V, Ozgocmen S, Pimentel-Santos FM, Reveille J, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Sampaio-Barros P, Wiek D, Braun J (2017) 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 76:978–991. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770

O’Dwyer T, O’Shea F, Wilson F (2015) Physical activity in spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 35:393–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-3141-9

O'Dwyer T, O'Shea F, Wilson F (2016) Decreased health-related physical fitness in adults with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional controlled study. Physiotherapy 102(2):202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.05.003

Halvorsen S, Vollestad NK, Fongen C, Provan SA, Semb AG, Hagen KB, Dagfinrud H (2012) Physical fitness in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: comparison with population controls. Phys Ther 92(2):298–309. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110137

Hsieh LF, Wei JC, Lee HY, Chuang CC, Jiang JS, Chang KC (2016) Aerobic capacity and its correlates in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheum Dis 19(5):490–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.12347

Mathieu S, Soubrier M (2018) Cardiovascular events in ankylosing spondylitis: a 2018 meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 78(6):e57. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213317

Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, Kvien TK, Dougados M, Radner H, Atzeni F, Primdahl J, Sodergren A, Wallberg Jonsson S, van Rompay J, Zabalan C, Pedersen TR, Jacobsson L, de Vlam K, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Semb AG, Kitas GD, Smulders YM, Szekanecz Z, Sattar N, Symmons DP, Nurmohamed MT (2017) EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 76(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209775

Al-Mallah MH, Sakr S, Al-Qunaibet A (2018) Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular disease prevention: an update. Curr Atheroscler Rep 20(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-018-0711-4

Sassen B, Cornelissen VA, Kiers H, Wittink H, Kok G, Vanhees L (2009) Physical fitness matters more than physical activity in controlling cardiovascular disease risk factors. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 16(6):677–683. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283312e94

Halvorsen S, Vollestad NK, Provan SA, Semb AG, van der Heijde D, Hagen KB, Dagfinrud H (2013) Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular risk in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional comparative study. Arthritis Care Res 65(6):969–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21926

Berg IJ, Semb AG, Sveaas SH, Fongen C, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK, Dagfinrud H, Provan SA (2018) Associations Between Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Arterial Stiffness in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Cross-sectional Study. J Rheumatol 45(11):1522–1525. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170726

Rausch Osthoff A-K, Juhl CB, Knittle K, Dagfinrud H, Hurkmans EJ, Braun J, Schoones J, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Niedermann K (2018) Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis. RMD Open 4:e000713. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000713

Niedermann K, Sidelnikov E, Muggli C, Dagfinrud H, Hermann M, Tamborrini G, Ciurea A, Bischoff-Ferrari H (2013) Effect of cardiovascular training on fitness and perceived disease activity in people with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res 65(11):1844–1852. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22062

Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, Duruoz T, Esbensen BA, Gunther KP, Hurkmans E, Juhl CB, Kennedy N, Kiltz U, Knittle K, Nurmohamed M, Pais S, Severijns G, Swinnen TW, Pitsillidou IA, Warburton L, Yankov Z, Vliet Vlieland TPM (2018) 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77(9):1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

Hannan AL, Hing W, Simas V, Climstein M, Coombes JS, Jayasinghe R, Byrnes J, Furness J (2018) High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training within cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sports Med 9:1–17. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajsm.S150596

Swain DP (2005) Moderate or Vigorous Intensity Exercise: Which Is Better for Improving Aerobic Fitness? Preventive Cardiol 8:55–58

Swain DP, Franklin BA (2006) Comparison of cardioprotective benefits of vigorous versus moderate intensity aerobic exercise. Am J Cardiol 97(1):141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.130

Niedermann K, Nast I, Ciurea A, Vliet Vlieland T, van Bodegom-Vos L (2018) Barriers and facilitators of vigorous cardiorespiratory training in axial Spondyloarthritis: Surveys among patients, physiotherapists, rheumatologists. Arthritis Care Res 71:839–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23705

Sveaas SH, Bilberg A, Berg IJ, Provan SA, Rollefstad S, Semb AG, Hagen KB, Johansen MW, Pedersen E, Dagfinrud H (2020) High intensity exercise for 3 months reduces disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA): a multicentre randomised trial of 100 patients. Br J Sports Med 54(5):292–297. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099943

van Genderen S, Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Heuft L, Luime J, Spoorenberg A, Arends S, Landewe R, Plasqui G (2015) Accelerometer quantification of physical activity and activity patterns in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and population controls. J Rheumatol 42(12):2369–2375. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.150015

Swinnen TW, Scheers T, Lefevre J, Dankaerts W, Westhovens R, de Vlam K (2014) Physical activity assessment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis compared to healthy controls: a technology-based approach. PLoS ONE 9(2):e85309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085309

O'Dwyer T, O'Shea F, Wilson F (2015) Decreased physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional controlled study. Rheumatol Int 35(11):1863–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3339-5

Haglund E, Bergman S, Petersson IF, Jacobsson LT, Strombeck B, Bremander A (2012) Differences in physical activity patterns in patients with spondylarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64(12):1886–1894. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21780

Fabre S, Molto A, Dadoun S, Rein C, Hudry C, Kreis S, Fautrel B, Pertuiset E, Gossec L (2016) Physical activity in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 203 patients. Rheumatol Int 36(12):1711–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3565-5

WHO (2010) Global recommendations on physical activity for health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Fimland MS, Vie G, Holtermann A, Krokstad S, Nilsen TIL (2018) Occupational and leisure-time physical activity and risk of disability pension: prospective data from the HUNT Study. Norway Occupat Environmental Med 75(1):23–28. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104320

Hall C, Heck JE, Sandler DP, Ritz B, Chen H, Krause N (2019) Occupational and leisure-time physical activity differentially predict 6-year incidence of stroke and transient ischemic attack in women. Scand J Work Environ Health 45(3):267–279. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3787

Holtermann A, Krause N, van der Beek AJ, Straker L (2018) The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. Br J Sports Med 52(3):149–150. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097965

Mundwiler J, Schupbach U, Dieterle T, Leuppi JD, Schmidt-Trucksass A, Wolfer DP, Miedinger D, Brighenti-Zogg S (2017) Association of occupational and leisure-time physical activity with aerobic capacity in a working population. PLoS ONE 12(1):e0168683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168683

Tsenkova VK (2017) Leisure-time, occupational, household physical activity and insulin resistance (HOMAIR) in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) national study of adults. Preventive Med Rep 5:224–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.12.025

Rausch Osthoff A-K, van der Giesen F, Meichtry A, Walker B, van Gaalen FA, Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, Peeters AJ, Niedermann K, Vliet Vlieland TPM (2019) The perspective of people with axial spondyloarthritis regarding physiotherapy: room for the implementation of a more active approach. Rheumatol Adv Practice. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkz043

Dagfinrud H, Halvorsen S, Vøllestad NK, Niedermann K, Kvien TK, Hagen KB (2011) Exercise programs in trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Do they really have the potential for effectiveness? Arthritis Care Res 63:597–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20415

Hilberdink B, van der Giesen F, Vliet Vlieland T, van Gaalen F, van Weely S (2019) Supervised group exercise in axial spondyloarthritis: patients' satisfaction and perspective on evidence-based enhancements. Arthritis Care Res 72:829–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23892

Hoogeboom TJ, Dopp CM, Boonen A, de Jong S, van Meeteren NL, Chorus AM (2014) THU0568 the effectiveness of exercise therapy in people with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 73:379–379

Di Carlo M, Lato V, Carotti M, Salaffi F (2016) Clinimetric properties of the ASAS health index in a cohort of Italian patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Health Quality Life Outcomes 14:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0463-1

Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, Akkoc N, Bautista-Molano W, Burgos-Vargas R, Wei JC, Chiowchanwisawakit P, Dougados M, Duruoz MT, Elzorkany BK, Gaydukova I, Gensler LS, Gilio M, Grazio S, Gu J, Inman RD, Kim TJ, Navarro-Compan V, Marzo-Ortega H, Ozgocmen S, Pimentel Dos Santos F, Schirmer M, Stebbings S, Van den Bosch FE, van Tubergen A, Braun J (2018) Measurement properties of the ASAS Health Index: results of a global study in patients with axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77(9):1311–1317. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212076

De Vries C, Hagenaars L, Kiers H, Schmitt M (2014) The physical therapist: a professional profile. KNGF. https://www.kngf.nl/binaries/content/assets/kngf/onbeveiligd/vakgebied/vakinhoud/beroepsprofielen/beroepsprofiel_eng_170314.pdf. Accessed May 11th 2020

Wagenmakers R, van den Akker-Scheek I, Groothoff JW, Zijlstra W, Bulstra SK, Kootstra JW, Wendel-Vos GC, van Raaij JJ, Stevens M (2008) Reliability and validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH) in patients after total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 9:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-9-141

Wendel-Vos G (2003) Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol 56(12):1163–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00220-8

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt-Glover MC, Leon AS (2011) 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(8):1575–1581. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12

Hilberdink B, van der Giesen F, Vliet Vlieland T, Nijkamp M, van Weely S (2020) How to optimize exercise behavior in axial spondyloarthritis? Results of an intervention mapping study. Patient Educ Couns 103(5):952–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.017

Corrado D, Migliore F, Basso C, Thiene G (2006) Exercise and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Herz 31(6):553–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-006-2885-8

Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, Blair SN, Corrado D, Estes NA 3rd, Fulton JE, Gordon NF, Haskell WL, Link MS, Maron BJ, Mittleman MA, Pelliccia A, Wenger NK, Willich SN, Costa F (2007) Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation 115(17):2358–2368. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.181485

Foster C, Farland CV, Guidotti F, Harbin M, Roberts B, Schuette J, Tuuri A, Doberstein ST, Porcari JP (2015) The Effects of high intensity interval training vs steady state training on aerobic and anaerobic capacity. J Sports Sci Med 14(4):747–755

Passalent LA, Soever LJ, O'Shea FD, Inman RD (2010) Exercise in ankylosing spondylitis: discrepancies between recommendations and reality. J Rheumatol 37(4):835–841. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.090655

Fongen C, Sveaas SH, Dagfinrud H (2015) Barriers and Facilitators for Being Physically Active in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Cross-sectional Comparative Study. Musculoskeletal Care 13(2):76–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1088

Pelle T, Claassen A, Meessen J, Peter WF, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Bevers K, van der Palen J, van den Hoogen FHJ, van den Ende CHM (2020) Comparison of physical activity among different subsets of patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis and the general population. Rheumatol Int 40(3):383–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04507-1

Arends S, Hofman M, Kamsma YP, van der Veer E, Houtman PM, Kallenberg CG, Spoorenberg A, Brouwer E (2013) Daily physical activity in ankylosing spondylitis: validity and reliability of the IPAQ and SQUASH and the relation with clinical assessments. Arthritis Res Ther 15(4):R99. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4279

Tyrrell JS, Redshaw CH (2016) Physical Activity in Ankylosing Spondylitis: evaluation and analysis of an eHealth tool. J Innov Health Inform 23(2):169. https://doi.org/10.14236/jhi.v23i2.169

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank all participants from the three participating hospitals. The authors also thank the Dutch Arthritis Society for funding this study (grant number: BP 14-1-161) and their patient representatives for pilot-testing the survey. Finally, the authors wish to thank Joséphine Peeters for her assistance in processing the data from the SQUASH questionnaire in SPSS.

Funding

Dutch Arthritis Society (ReumaNederland), grant number: BP 14-1-161.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors Bas Hilberdink, Thea Vliet Vlieland, Florus van der Giesen, Floris van Gaalen, Robbert Goekoop, Andreas Peeters, Marta Fiocco and Salima van Weely declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Related congress abstract publication:

We presented the data as a poster at the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR 2019) and an abstract has therefore been published: Hilberdink, B., Van der Giesen, F., Vliet Vlieland, T., Van Gaalen, F., Ronday, K., Peeters, A., Van Weely, S. (2019). FRI0376 Differences in physical activity between axial spondyloarthritis patients with and without physical therapy. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 78, 870–871.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hilberdink, B., Vlieland, T.V., van der Giesen, F. et al. Adequately dosed aerobic physical activity in people with axial spondyloarthritis: associations with physical therapy. Rheumatol Int 40, 1519–1528 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04637-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04637-x