Abstract

To compare the amount of physical activity (PA) among patients with different subsets of knee or hip osteoarthritis (OA) and the general population. Secondary analyses of data of subjects ≥ 50 years from four studies: a study on the effectiveness of an educational program for OA patients in primary care (n = 110), a RCT on the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary self-management program for patients with generalized OA in secondary care (n = 131), a survey among patients who underwent total joint arthroplasty (TJA) for end-stage OA (n = 510), and a survey among the general population in the Netherlands (n = 3374). The Short QUestionnaire to ASssess Health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH) was used to assess PA in all 4 studies. Differences in PA were analysed by multivariable linear regression analyses, adjusted for age, body mass index and sex. In all groups, at least one-third of total time spent on PA was of at least moderate-intensity. Unadjusted mean duration (hours/week) of at least moderate-intensity PA was 15.3, 12.3, 18.1 and 17.8 for patients in primary, secondary care, post TJA, and the general population, respectively. Adjusted analyses showed that patients post TJA spent 5.6 h [95% CI: 1.5; 9.7] more time on PA of at least moderate-intensity than patients in secondary care. The reported amount of PA of at least moderate-intensity was high in different subsets of OA and the general population. Regarding the amount of PA in patients with different subsets of OA, there was a substantial difference between patients in secondary care and post TJA patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) are among the most common joint conditions, with treatment being predominantly symptomatic and focused on controlling pain, improving function, and health-related quality of life. In all stages of knee or hip OA, promotion of general physical activity (PA) is, in parallel with joint-specific exercises, considered to be a key component in the conservative management, including the trajectory after total joint arthroplasty (TJA) [1,2,3,4,5,6]. PA is defined by the World Health Organization as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” [7, 8]. According to this definition, PA is not only restricted to exercise but also comprises any activity in any domain of daily life, e.g. commuting, work activities, cycling, gardening, household activities and sports [9].

PA has multiple potential benefits in patients with knee or hip OA, as it has proven to play a role in improvement of pain, physical function, mobility, and weight management [1, 6, 10,11,12,13]. In addition, PA is considered an important preventive measure for other chronic diseases (e.g. cardiovascular disease) associated with OA [11, 14,15,16].

The proportion of OA patients meeting public health recommendations for health-enhancing PA varies largely in the literature, from 13 to 60% [14, 17,18,19]. This variation could probably be due to heterogeneity in participants, settings, monitoring devices and methods across studies [17]. Currently, studies that compare the amount of PA between early and advanced stages of knee and or hip OA, including TJA, and the general population are scarce [17, 19, 20]. Regarding the comparison of PA in patients before and after TJA, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that PA does not change 6 months post-TJA compared with preoperative levels [20, 21]. Moreover, these studies concluded that PA after TJA was less compared to that of healthy controls [20,21,22]. On the other hand, Meessen et al. found that patients following TJA were more physically active compared to the general population [23]. In none of the aforementioned studies, the nature of performed activities in different stages of the disease was presented.

It is conceivable that pain is a barrier for performing PA, and pain increases in more advanced stages of OA. Therefore, one would expect that PA decreases over the course of knee or hip OA [24, 25] and that the amount of PA of patients with OA is lower than that of the general population. On the other hand, we expect that patients after total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perform more PA than patients with advanced OA but without indication for surgery, since TJA results in less pain and improved function [14, 17].

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to deepen the insight in terms of amount and nature of self-reported PA levels in different stages of the disease (i.e. patients in primary and secondary care and post-TJA) and to compare PA characteristics of patients with knee or hip OA with those of the general Dutch population.

Methods

Study design

This study has an observational cross-sectional design; research questions were answered by secondary analyses of data from four studies performed in the Netherlands in four different populations: (1) patients with knee or hip OA in primary care [26], (2) patients with generalized OA in secondary care [27], (3) patients with knee or hip OA who underwent TJA [23, 28], and (4) the general population [29]. Only data of subjects ≥ 50 years were included in this study.

Participants

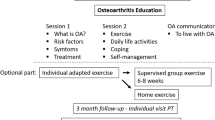

Patients in primary care

Baseline data of an observational study to determine (preliminary) effects of an OA educational, community-based programme on healthcare utilization and clinical outcomes were used [26]. This educational programme consisted of two 1.5-h meetings, led by a physiotherapist and a GP, with information on OA and its disease course, conservative treatment modalities using a stepped-care approach, and surgical treatment options. Patients were recruited through searching general practitioners (GPs) electronic patient records and advertisements in local newspapers. In total, 148 patients with a clinical diagnosis of knee or hip OA were included from the region of Nijmegen between October 2015 and March 2016 [26]. Main inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in the supplementary material.

Patients in secondary care

We used baseline data of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of two non-pharmacological multidisciplinary self-management programmes for generalized OA in secondary care (i.e. face-to-face versus a telephone-based). Patients who visited the outpatient department of the Sint Maartenskliniek at Nijmegen in 2010 were included if they were clinically diagnosed with generalized OA and referred by their rheumatologist for multidisciplinary treatment. A total of 147 patients completed baseline assessments [27].

Total joint arthroplasty (total knee and hip arthroplasty)

For the post-TJA stage, we used data from a cross-sectional study on patients who underwent total knee or hip joint arthroplasty due to end-stage OA. The original study was conducted to make an inventory of the use of physical therapy and the presence of comorbidities after TJA. Orthopaedic surgeons of four different hospitals invited by mail all patients who underwent TJA in the preceding 7–22 months to participate in this study. In total, 522 patients responded [23, 28]. Results on the comparison of the amount of PA between TJA patients and the general population were previously published [23], and will thus not be highlighted in this study.

General population

Data from the general Dutch population were obtained from a nationwide survey on general health (Gezondheidsmonitor 2012). Annually this survey is distributed (randomly) amongst more than 14,000 residents in the Netherlands, collected by the Dutch National Bureau of Statistics [29]. First, the survey on basic characteristics was sent to people living in private households, with a response rate of 60–65%. Subsequently, responders aged ≥ 12 years received a questionnaire regarding PA among other health-related subjects. Response rate of the health-related questionnaire was 55% [29]. This survey yielded individual participant data and was obtained from the CBS [29].

Ethical approval for this study was asked for and waived by the local Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre, Leiden (Protocol Number: G17.113, Date: 2 November 2017). The study fell outside the remit of the law for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, and was approved by the local ethical committee.

Assessments

Sociodemographic characteristics

All databases included the following demographic characteristics: sex (male / female), age, body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and included information about marital status.

Physical activity

In all databases, PA was assessed with the validated Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (SQUASH) [9, 30]. The SQUASH is a structured questionnaire consisting of activities at work, commuting, household activities, leisure time, and sport activities. Additionally, persons who filled out the SQUASH were asked to report the nature of (up to) four sports activities they actually perform. From this questionnaire, we calculated the mean duration of PA at low intensity (< 4 metabolic equivalent of task (MET) for persons < 55 years and < 3 for persons ≥ 55 years), mean duration of PA at moderate intensity (≥ 4 and < 6.5 MET for persons < 55 years and activities ≥ 3 and < 5.0 MET for persons ≥ 55 years) and mean duration of PA at vigorous intensity (≥ 6.5 MET for people < 55 years and ≥ 5 MET for ≥ 55 years). We combined the latter two categories into PA of at least moderate intensity. The MET for an activity was derived from the Ainsworth compendium [31].

Statistical analysis

Baseline descriptive statistics for each group were provided as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and numbers (N) with percentages (%) for nominal variables. We performed a mean centering operation for the variables age and BMI.

To compare mean amount (hours/week) of total PA and PA of at least moderate intensity between three stages of OA and the general population, we performed multivariable linear regression analyses. All regression analyses were performed on complete cases adjusted for (mean centered) age, (mean centered) BMI and sex. Subsequently, the residuals of the linear regression analyses were plotted to inspect normality assumptions. On the basis of the residual plots, we concluded that transformation of the continuous data would not improve the accuracy of the models.

The seven most frequently reported sport activities are presented per subgroup separately. We refrained from statistical testing, because a type I error could occur due to multiple testing.

Sensitivity analyses

As OA is a prevalent disease, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients with a possible diagnosis of OA from the general population. Therefore, we repeated all analyses excluding participants from the general population with a positive answer on the question whether they suffered from “wear and tear of the joints” (yes/no) in the preceding 12 months.

A p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 [32].

Results

Participants

In total, the present study used data of 4125 patients with hip or knee OA or from the general population aged ≥ 50 years who completed the SQUASH questionnaire. Datasets representing the primary and secondary care patients comprised 110 and 131 participants, respectively. The dataset representing patients after TJA consisted of 510 participants. The database from the general (Dutch) population of 14,374 persons contained 3,374 persons who filled out the SQUASH and were ≥ 50 years of age and thus met inclusion criteria for the present study. Of these latter 3374 persons, 853 (25.3%) reported that they suffered from “wear and tear of the joints” in the previous 12 months.

Patients’ demographics and characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the patients selected for the present analysis in all four study populations. The mean age was highest in patients after TJA [70.5 years (SD 8.5)] and lowest [61.1 (SD 6.7)] in the secondary care group. The proportion of males was lowest in the secondary care subgroup (15.3%) and highest in the general population (50.5%). The lowest mean BMI was found in the general population [26.1 kg/m2 (SD 4.1)] and the highest [27.8 kg/m2 (SD 4.5)] was found in both secondary care patients and in patients post-TJA.

Symptoms in both knee(s) and hip(s) were perceived by almost 25% in primary care patients and 50% in secondary care patients. In the TJA group, 273 (53.5%) patients received TKP and 237 (46.5%) THP, Table 1.

Physical activity

The percentage of missing data on the primary outcomes was approximately 3% for total duration. Table 2 shows the mean duration of PA (unadjusted for age, BMI and sex) for the different subgroups.

Regarding the total amount of PA (light, moderate, and vigorous intensity), the mean duration (unadjusted for age, BMI and sex) in the different subgroups ranged from 36.0 (19.5) hours/week for primary care patients to 40.1 (26.9) hours/week for the general population. Results of multiple linear regression analyses, adjusted for (mean centered) age, (mean centered) BMI and sex, shows that patients post-TJA were on average 10.9 [95% CI: 5.7; 16.1] (p = 0.000) hours/week more active than secondary care patients and 6.1 [95% CI: 3.5; 8.7] (p = 0.000) hours/week more active than the general population (Table 3). Adjusted analyses also showed that patients in secondary care were on average 4.7 [95% CI: − 9.4; − 0.1] (p = 0.046) hours/week less active than the general population.

The mean duration of PA of at least moderate intensity (unadjusted) ranged from 12.3 (12.0) hours/week for secondary care patients to 18.1 (17.8) hours/week for patients post-TJA, Table 2. Adjusted analyses revealed that patients post-TJA were on average 5.6 [CI 1.5; 9.7] (p = 0.007) hours/week more active on PA of at least moderate intensity than patients in secondary care and 2.4 [CI 0.3; 4.5] (p = 0.022) hours/week more active than the general population (Table 4).

We found comparable patterns in differences between groups in PA of light, moderate or vigorous intensity (see supplement 2, 3 and 4).

The proportions of people spending a certain amount of time on total PA and PA of at least moderate intensity for each subgroup are displayed in Fig. 1. The proportion of people at least spending 150 min per week on PA of at least moderate intensity ranged from 84.7% to 92.1%. The proportion of people at least spending 300 min per week on PA of at moderate intensity ranged from 73.7% to 81.5% (Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses, excluding persons reporting “wear and tear” of the joints in the general population yielded similar results for all performed analyses. Additional sensitivity analyses, separating the TJA group in TKP and THP, showed that the mean duration of PA in patients with TKP was 3.0 [0.1; 6.0] hours/week higher than the general population, whereas no significant difference was found between patients after THP and the general population (2.0 [− 0.8; 4.7]).

Nature of physical activities

Table 5 shows the seven most frequently reported sports activities, presented per subgroup. Patients after TJA least frequently reported fitness as performed activity, whereas they reported cycling most often. General exercise at moderate intensity is reported more often by OA patients than the general population. Yoga is more often reported by primary and secondary care patients. Patients in secondary care reported swimming most often. We visually inspected differences in proportions between groups, thus no statistical testing was performed.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to document the amount and nature of PA among patients with OA in different stages of their disease and to compare PA characteristics of patients with knee or hip OA with those of the general population. On average, patients reported to be physically active for at least 5.1 h per day, and to spend about one-third of PA in at least moderate-intensity PA. We found that OA patients after TJA are on average more physically active than patients in secondary care. No other relevant differences across different stages of osteoarthritis (OA) and the general population were found.

We found differences in the nature of PA that patients perform in different stages of OA and the general population: patients after TJA report more often low-impact activities (e.g. aerobic exercise (general exercises at moderate-intensity) and cycling) than other OA patients and the general population. On the other hand, swimming, also considered a low-impact activity, is most often reported by patients in secondary care. A possible explanation for the differences in the nature of PA is that high-impact sports such as running and contact sports are discouraged for patients after TJA [33,34,35]. Our findings are in line with a meta-analysis concluding that patients after TJA return more often to low-impact activities than high-impact activities [36]. This may indicate that patients after TJA follow rehabilitation advice.

International guidelines recommend to perform at least 150 min per week of PA on at least moderate intensity for general health benefits [8, 37]. The WHO states that there is evidence for additional health benefits up to 300 min per week [8]. However, recommendations about the optimal amount and intensity of PA for OA patients are lacking. Apart from general health benefits, it is well known that increasing PA has positive effects on pain in OA patients [1, 10], suggesting a dose–response relationship. Currently, there is debate about the exact shape of the dose–response relationship between performed PA and health benefits [38,39,40]. Some research groups assume a (curvi)linear relationship implying the more PA the better [37, 41, 42], whereas other research groups assume an optimal range beyond which health benefits may be partially lost [38,39,40]. Epidemiologic studies on the optimal dose of PA are, however, mainly performed in cardiovascular patients and physically active volunteers rather than in OA patients. Therefore, future studies should assess the exact relation between PA and actual health benefits in OA patients to determine the optimal dose of PA.

We could not confirm our first hypothesis that the duration of PA decreases over the course of OA. Subgroups in the present study were based on the assumption that primary care patients (recruited trough searching GP electronic patients records and advertisements in local newspapers) and secondary care patients (recruited after referral by a rheumatologist to self-management programme of a hospital) reflect increasing rates of severity, rather than upon well-accepted criteria (i.e. Kellgren and Lawrence classification or joint space width). Our results are in line with a meta-analysis, showing no clear differences in PA between mild or moderate and severe OA [17]. A possible explanation could be that patients with more severe knee or hip OA substitute activities so that PA can be performed despite their complaints. However, our findings are contradictory with results of a longitudinal study in over 1200 OA patients showing that the amount of PA decreases with 11% over the course of 4 years [24]. The observed decrease in PA over time in the latter study could be explained by the influence of ageing; higher age is associated with lower PA levels [20, 43]. Future studies should focus on unravelling the influence of ageing and severity of the disease on PA in OA patients.

Additionally, we could not confirm our hypothesis that patients in primary and secondary care were less active than the general population. Our results are in line with a recent study showing comparable levels of objectively measured activity of at least moderate intensity for patients with knee OA and the general population [44]. On the other hand, our findings are inconsistent with a study concluding that patients with end-stage OA were less active than controls [45]. However, it is likely that in the latter study more severely affected patients were included. Our findings suggest that having OA in the early and more advanced stages does not impact PA levels, and that patients with OA manage to stay as active as the general population. However, prospective longitudinal research is needed to study the impact of symptoms related to OA on actual PA levels.

This study confirms our second hypothesis that patients who underwent TJA are more physically active than patients in secondary care. Regarding the effect of TJA on PA, recent studies showed no differences in preoperative PA levels compared to 6, 12 and 24 months after TJA, as well as compared to matched controls [20, 21, 46]. There are several possible explanations that patients following TJA spent more time on PA in our study. First, TJA results in less pain and improved function [14, 17]. Second, in our sample, 50% of patients received physical therapy for more than 3 months after TJA [28]. Therefore, these patients could be better instructed and motivated to perform PA. Another explanation could be that relatively active patients with end-stage OA receive TJA, and will therefore resume their old PA level easily.

This is the first study that compares the amount of PA in different stages of OA and the general population. This study also reports activities that are actually performed in different stages of OA and in the general population. However, data must be interpreted with caution, since this study has some potential limitations. Compared to the literature, we studied a relatively physically active cohort of patients [17, 43, 47], however, comparison with studies utilizing objective measures of PA (e.g. accelerometers) should be done with caution. Despite the regular use of self-administered measures, questionnaires tend to overestimate PA [30]. The SQUASH takes walking and cycling into account in three different modules; commuting, recreational and as a sports activity, and overlap in reporting these activities cannot be excluded. In particular, overestimation of the amount of PA spent on cycling, a common daily activity in the Netherlands, is likely. On the other hand, all datasets in this study used the same questionnaire assessing PA, i.e. the SQUASH, and, in our view, our results regarding differences between groups are valid. A note of caution is due here since we compared baseline data of four separate, previously published studies of different clinical settings in different time periods. Due to the heterogeneity of the subjects included in the separate studies, it is possible that there is some overlap in patients’ characteristics among different subsets of OA patients. The subgroups comprising OA patients in different stages of disease were relatively small, and this could result in lack of power. Although we adjusted for age, sex and BMI, we cannot rule out possible confounding of other factors such as education, profession, and comorbidities not included in our analysis. However, sample sizes were appropriate to detect differences of 10% or higher.

In conclusion, this study showed that patients with different subsets of OA and the general population spend on average considerable time on PA and that at least one-third of time active was spent on PA of at least moderate intensity. On the one hand, we found no major differences in the amount of PA among OA patients in primary, secondary care and the general population, and on the other hand we found substantial differences in the amount of PA between patients in secondary care and post-TJA patients. Although we found that PA levels for patients in different subsets of OA and the general population were comparable, it is well known that PA has beneficial effects on OA symptoms. Thus, continued efforts are needed to enhance PA in patients in different stages of OA. More research is needed to assess the exact relation between PA (in terms of duration and intensity) and actual health benefits in patients with OA over time.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data from the nationwide survey on health is only available at the Central bureau of Statistics after permission is granted by the “Data Archiving and Networking Services”.

Abbreviations

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- TJA:

-

Total joint arthroplasty

- SMK:

-

Sint Maartenskliniek Hospital

- LUMC:

-

Leiden University Medical Center

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- COPD:

-

Chronis obstructive pulmonary disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

References

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ et al (2013) EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72:1125–1135. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT et al (2012) American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:465–474

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al (2014) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 22:363–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al (2008) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil 16:137–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013

Smink AJ, van den Ende CHM, Vliet Vlieland TPM et al (2011) “Beating osteoARThritis”: Development of a stepped care strategy to optimize utilization and timing of non-surgical treatment modalities for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 30:1623–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-011-1835-x

Rausch Osthoff A-K, Niedermann K, Braun J et al (2018) 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77:1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM (1985) Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 100:126–131

(2011) Global recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Wendel-Vos GCW, Schuit AJ, Saris WHM, Kromhout D (2003) Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol 56:1163–1169

Lee K, Cooke J, Cooper G, Shield A (2017) Move it or lose it. is it reasonable for older adults with osteoarthritis to continue to use paracetamol in order to maintain physical activity? Drugs Aging 34:417–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0450-1

Warburton DER (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can Med Assoc J 174:801–809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351

Chmelo E, Nicklas B, Davis C et al (2013) Physical activity and physical function in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Phys Act Health 10:777–783. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24007

Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Grant RL (2008) Care and management of osteoarthritis in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 336:502–503. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39490.608009.AD

Kahn TL, Schwarzkopf R (2015) Does total knee arthroplasty affect physical activity levels? Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Arthroplasty 30:1521–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.016

Hoogeboom TJ, den Broeder AA, Swierstra BA et al (2012) Joint-pain comorbidity, health status, and medication use in hip and knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:54–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20647

Altman RD (2010) Early management of osteoarthritis. Am J Manag Care 16:S41–S47

Wallis JA, Webster KE, Levinger P, Taylor NF (2013) What proportion of people with hip and knee osteoarthritis meet physical activity guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil 21:1648–1659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.003

Plotnikoff R, Karunamuni N, Lytvyak E et al (2015) Osteoarthritis prevalence and modifiable factors: a population study. BMC Public Health 15:1195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2529-0

Hootman JM, Macera CA, Ham SA et al (2003) Physical activity levels among the general US adult population and in adults with and without arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 49:129–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10911

Arnold JB, Walters JL, Ferrar KE (2016) Does physical activity increase after total hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis? A systematic review. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 46:431–442. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.6449

Hammett T, Simonian A, Austin M et al (2018) Changes in physical activity after total hip or knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of six- and twelve-month outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70:892–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23415

Kersten RFMR, Stevens M, van Raay JJAM et al (2012) Habitual physical activity after total knee replacement. Phys Ther 92:1109–1116. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110273

Meessen JMTA, Peter WF, Wolterbeek R et al (2017) Patients who underwent total hip or knee arthroplasty are more physically active than the general Dutch population. Rheumatol Int 37:219–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3598-9

Hoogeboom TJ, den Broeder AA, de Bie RA, van den Ende CHM (2013) Longitudinal impact of joint pain comorbidity on quality of life and activity levels in knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Rheumatology 52:543–546. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes314

Song J, Chang AH, Chang RW et al (2018) Relationship of knee pain to time in moderate and light physical activities: Data from osteoarthritis initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum 47:683–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.005

Claassen AAOM, Schers HJ, Koëter S et al (2018) Preliminary effects of a regional approached multidisciplinary educational program on healthcare utilization in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract 19:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0769-7

Cuperus N, Hoogeboom TJ, Kersten CC et al (2015) Randomized trial of the effectiveness of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary face-to-face treatment program on daily function compared to a telephone-based treatment program in patients with generalized osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 23:1267–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2015.04.007

Peter WF, Dekker J, Tilbury C et al (2015) The association between comorbidities and pain, physical function and quality of life following hip and knee arthroplasty. Rheumatol Int 35:1233–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3211-7

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS) (2014) Gezondheidsenquête 2012. DANS

Wagenmakers R, van den Akker-Scheek I, Groothoff JW et al (2008) Reliability and validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH) in patients after total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:141. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-9-141

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD et al (2011) 2011 compendium of physical activities. Med Sci Sport Exerc 43:1575–1581. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12

StataCorp (2013) Stata statistical software: release 13. StataCorp LP, College Station=

Jones DL, Cauley JA, Kriska AM et al (2004) Physical activity and risk of revision total knee arthroplasty in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a matched case-control study. J Rheumatol 31:1384–1390

Crowther JD, Lachiewicz PF (2002) Survival and polyethylene wear of porous-coated acetabular components in patients less than fifty years old: results at nine to fourteen years. J Bone Jt Surg Am 84-A:729–735

Duffy GP, Berry DJ, Rowland C, Cabanela ME (2001) Primary uncemented total hip arthroplasty in patients %3c 40 years old: 10- to 14-year results using first-generation proximally porous-coated implants. J Arthroplasty 16:140–144

Witjes S, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PPFM et al (2016) Return to sports and physical activity after total and unicondylar knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Med 46:269–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0421-9

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR et al (2011) Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43:1334–1359. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

Mons U, Hahmann H, Brenner H (2014) A reverse J-shaped association of leisure time physical activity with prognosis in patients with stable coronary heart disease: evidence from a large cohort with repeated measurements. Heart 100:1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305242

Maessen MFH, Verbeek ALM, Bakker EA et al (2016) Lifelong exercise patterns and cardiovascular health. Mayo Clin Proc 91:745–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.028

Eijsvogels TMH, Thompson PD, Franklin BA (2018) The “Extreme Exercise Hypothesis”: recent findings and cardiovascular health implications. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 20:84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-018-0674-3

Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A et al (2015) Leisure time physical activity and mortality. JAMA Intern Med 175:959. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533

Pandey A, Garg S, Khunger M et al (2015) Dose-response relationship between physical activity and risk of heart failure: a meta-analysis. Circulation 132:1786–1794. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015853

Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA et al (2011) Objective physical activity measurement in the osteoarthritis initiative: are guidelines being met? Arthritis Rheum 63:3372–3382. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30562

Thoma LM, Dunlop D, Song J et al (2018) Are older adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis less active than the general population? analysis from the osteoarthritis initiative and the national health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70:1448–1454. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23511

de Groot IB, Bussmann JB, Stam HJ, Verhaar JAN (2008) Actual everyday physical activity in patients with end-stage hip or knee osteoarthritis compared with healthy controls. Osteoarthr Cartil 16:436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2007.08.010

Smith TO, Mansfield M, Dainty J et al (2018) Does physical activity change following hip and knee replacement? Matched case-control study evaluating Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Physiotherapy 104:80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2017.02.001

Farr JN, Going SB, Lohman TG et al (2008) Physical activity levels in patients with early knee osteoarthritis measured by accelerometry. Arthritis Rheum 59:1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24007

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants of the original studies and the health survey. A special thanks to the researchers and orthopaedic surgeons involved in the original data collection (H.M.J. van der Linden, H.M. Vermeulen, R.G.H.H. Nelissen, S.C. Cannegieter, C. Tilbury and R. Wolterbeek of LUMC, Leiden) (M.R. Bénard and S.B. Vehmeijer of Reinier de Graaf Groep, Delft) (R. Onstenk of Groene Hart Ziekenhuis Gouda) (R. Tordoir and S.H.M. Verdegaal of Alrijne Ziekenhuis Leiderdorp).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TP, AAOMC, CHMvdE, and JMTAM participated in the design of the study. TP, AAOMC, WFP carried out the data collection. TP, AAOMC, JMTAM, WFP, TPMVV, KB, JvdP, FHJvdH and CHMvdE, were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data. TP, AAOMC and CHMvdE were responsible for drafting the article, all other authors critical reviewed the article. Furthermore, all authors take full responsibility for the integrity of the study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was asked for and waived by the local Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center, Leiden (Protocol Number: G17.113). The observational study and RCT regarding baseline data of primary and secondary care patients were registered in the Dutch Trial Register (trial number NTR5472 and NTR2137, respectively). The health monitor conducted by CBS fell outside the remit of the law for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. Also the original studies regarding primary, and secondary care and TJA patients fell outside the remit of the law for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, and were approved by the local ethical committees (i.e. Leiden and CMO Arnhem-Nijmegen).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pelle, T., Claassen, A.A.O.M., Meessen, J.M.T.A. et al. Comparison of physical activity among different subsets of patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis and the general population. Rheumatol Int 40, 383–392 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04507-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04507-1