Abstract

Background

Effective treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with biologic DMARDs poses a significant economic burden. The AMPLE (Abatacept versus adaliMumab comParison in bioLogic-naïvE RA subjects with background methotrexate) trial was a head-to-head, randomized study comparing abatacept with adalimumab. A post hoc analysis showed improved efficacy for abatacept in patients with versus without seropositive, erosive early RA.

Objective

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the cost per response (ACR20/50/70/90 and HAQ-DI) and patient in remission (DAS28-CRP, CDAI, and SDAI) for abatacept relative to adalimumab, in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada.

Methods

A previously published model was used to compare abatacept and adalimumab in a cohort of 1000 patients over 2 years. Clinical inputs were updated based on two subpopulations from the AMPLE trial. Cohort 1 included patients with early RA (disease duration ≤ 6 months), RF and/or ACPA seropositivity, and > 1 radiographic erosion. Cohort 2 included patients with RA in whom at least one of these criteria was absent.

Results

For cohort 1, all incremental costs per additional health gain (patient response or patient in remission) favoured abatacept in all countries, except for DAS28-CRP remission in Canada. Cost savings versus adalimumab were greater when more stringent response criteria were applied and also in cohort 1 patient (versus cohort 2 patients).

Conclusion

The cost per responder and patient in remission favoured abatacept in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA across all the countries. In this patient population, the use of abatacept instead of adalimumab can lead to lower costs in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, progressive, systemic autoimmune disease. The course of RA is variable, and is characterized by inflammation and swelling of synovial joints that often progresses to destructive joint disease, joint damage, impaired joint function, pain, tenderness, increasing disability, and even cardiovascular mortality [1,2,3]. RA has a significant economic burden, due to both direct medical and non-medical costs and indirect costs; Lundkvist et al. [4] estimated the total health costs (direct, indirect, and informal care) of RA to be approximately €45 billion per year in Europe and €41.6 billion in the US.

Payers’ attention has been drawn to RA over the years due to its high epidemiological impact, relatively early age at disease onset, chronic nature, high rate of comorbidities, and effects on patients’ disability, quality of life, and work productivity [5]. The introduction of effective, though more expensive, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) has further increased the level of attention on this condition.

According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [6] and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines [7], abatacept, a selective T-cell co-stimulation modulator, is included as an option for use as a first-line bDMARD in patients with an inadequate response to the conventional DMARD therapy. These guidelines place abatacept alongside TNF-alpha inhibitors, which have traditionally been the main first-line biologic therapy.

Adalimumab is a fully human TNF-alpha inhibitor approved for active rheumatoid arthritis. The AMPLE (Abatacept versus adaliMumab comParison in bioLogic-naïvE RA subjects with background methotrexate) trial was a 2-year, head-to-head, randomized study (1-year primary endpoint) comparing subcutaneous (SC) abatacept 125 mg weekly with SC adalimumab 40 mg every other week, both in combination with a stable dose of methotrexate (≥ 15 and ≤ 25 mg/week or ≥ 7.5 mg/week if documented intolerance to higher doses). Clinical outcomes evaluated included: American College Rheumatology ACR 20, 50, 70, and 90 responses, changes in Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C-reactive protein level (DAS28-CRP) score, DAS28-CRP < 2.6 and ≤ 3.2, improvement in the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI) ≥ 0.3 units, and remission (post hoc analysis) [8,9,10]. Safety assessments were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Adverse events (AEs) of special interest included infections, autoimmune events, malignancy, and injection site reactions (ISRs). Efficacy and safety outcomes were evaluated at days 1, 15, 29, and every 4 weeks thereafter during year 1, and every 3 months during year 2. Clinical assessors were blinded to patient treatment and assessed patients’ joints, disease activity, and defined AE causality [11].

The AMPLE trial demonstrated similar clinical efficacy for abatacept and adalimumab based on clinical, functional, and radiographic outcomes, with some notable differences in safety [11, 12]. Post hoc analyses of the AMPLE trial showed improved efficacy for patients with higher ACPA titre levels compared with ACPA-negative patients. This effect was observed in both clinical efficacy measures (ACR20, 50, 70, 90, and DAS28-CRP) and in health-related quality of life (HAQ-DI) [11].

Anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity are prognostic factors for more severe and erosive RA [13]. The presence of seropositivity (ACPA or RF positive) and erosions has been noted in the EULAR treatment guidelines to identify patients with RA, who require the early and aggressive clinical intervention [13]. As disease in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA is mostly driven by immunological features, response to RA therapy may vary [12]. Recently, new post hoc analyses of the AMPLE trial confirmed improved efficacy for abatacept in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA (defined as: disease duration ≤ 6 months, RF or ACPA seropositivity, and > 1 radiographic erosion) compared with adalimumab [12]. A disease duration of 6 months was used, because it is more stringent than most definitions [14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and mimics the referral pattern to rheumatologists for diagnosis and initiation of DMARD therapy.

A cost–consequence analysis based on the AMPLE trial has previously been published to evaluate the cost per response and per patient in remission in ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients [21]. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the cost per response and per patient in remission for abatacept relative to adalimumab, both in combination with methotrexate, in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada.

Methods

A previously published deterministic decision tree was used to compare the cost per response and per patient in remission (cost–consequence analysis) for abatacept and adalimumab in a cohort of 1000 patients over a 2-year time horizon from the perspective of US, German, Spanish, and Canadian healthcare payers [21]. This type of analysis is a variant of a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), presenting health-related outcomes alongside costs and subsequently their relative value between alternatives, allowing decision-makers to form their own view of the relative importance of each outcome [22]. This approach was taken due to the difficulty in identifying one single outcome to express all health benefits of a treatment option for RA.

Patient characteristics were based on the baseline characteristics from the AMPLE trial [23, 24]. Costs in the model included direct medical costs; no discounting was applied due to the short time horizon. Efficacy-related outcomes in the model were determined by the percentage of responding patients according to ACR or HAQ-DI and the percentage of patients in remission according to the disease activity score in 28 joints using the C-reactive protein level (DAS28-CRP), the clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and simplified disease activity index (SDAI). The safety-related outcomes were determined by the incidence of frequent adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), local injection site reactions (LISRs), malignancies not already included as SAEs, and autoimmune disorders. The main outcome measures of interest were the total health benefits and costs per health gain. The costs per health care gain were expressed as the incremental cost per additional responding patient or patient in remission with abatacept versus adalimumab. One-way sensitivity analyses (OWSA) were performed to assess the impact of model inputs on the difference in total costs.

Our research does not involve human participants or personal data. Therefore, no ethics approval was required. The AMPLE study on which this analysis was based did have the required ethics approval and this is mentioned in the main publication [11].

Efficacy and safety

Clinical inputs were updated based on a post hoc analysis of the AMPLE trial, which compared efficacy and safety outcomes for patients in two subpopulations by treatment arm (Table 1). Cohort 1 included patients with early RA (disease duration ≤ 6 months), RF and/or ACPA seropositivity, and > 1 radiographic erosion. Cohort 2 included patients with RA in whom at least one of these criteria was absent (i.e., the remaining AMPLE population) [12].

Costs

Costs for abatacept and adalimumab were updated across all countries to reflect 2017 costs (Table 2). For the US, all unit costs were updated; for abatacept, adalimumab, methotrexate, and concomitant treatments, wholesale prices were taken from the First Databank: AnalySource [25]. In addition, disease monitoring costs, AE costs, and societal costs from 2014 were inflated to 2017 costs using the medical care category of the Consumer Price Index [26]. For Germany, unit prices were retrieved from the Lauer-Taxe database and calculated based on the list public price per pack (APU/HAP) minus the mandatory rebate price (pre-AMNOG) minus the mandatory pharmacy rebate price (Pfichtrabatt Apotheke) [27]. For Spain, study drug unit costs and concomitant drug costs were obtained from a national database [28], and the list price was used minus the 7.5% mandatory discount to the Spanish National Health System (SNHS). Other hospital cost items were derived from DRGs, which are based on Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE-9) tariffs paid to the hospital by the SNHS [29], and the Spanish Healthcare database eSalud [30]. The unit price for abatacept for Canada was taken from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Exceptional Access Program (EAP) database [31], and for adalimumab, the drug price was based on the Ontario MOHLTC Drug Benefit (ODB) formulary [32].

Additional analyses: indirect costs

Additional analyses to incorporate the societal perspective and indirect non-medical costs were performed for all countries. The costs of work absence, productivity loss due to early retirement, and patient out-of-pocket costs were included in the model based on the findings of Kobelt et al. [33], who showed an association between HAQ-DI response levels and increased costs. The model calculates societal costs by combining the cost per HAQ-DI response level, where increasing levels indicate less favourable response, and the associated cost for that category. As the costs from Kobelt et al. were based on Swedish patients, costs were converted to the respective currencies in the US, Spain, and Canada using purchase power parities and inflated to 2017 values using the consumer price index. For Germany, costs were obtained from a database study of German patients with RA aged 18–64 [34].

Results

Health benefits

Health benefits over 2 years are described in Table 3. Results for cohort 1 consistently favoured abatacept over adalimumab over 2 years, across all response criteria and for CDAI and SDAI remission. In cohort 2, results for abatacept were less consistent, with less pronounced differences compared with adalimumab.

Fewer patients discontinued abatacept treatment compared with adalimumab in both cohorts. Lack of efficacy was more often reported to be the reason of abatacept discontinuation in cohort 2. However, fewer patients discontinued abatacept treatment because of lack of efficacy in cohort 1. In addition, fewer patients discontinued abatacept treatment because of safety reasons compared with adalimumab in both cohorts (Cohort 1: 26 patients vs. 111 patients; Cohort 2: 36 patients vs. 88 patients). This was also reflected in the lower number of serious adverse events and local injection site reactions when treated with abatacept across both cohorts.

Costs

Total costs for abatacept were lower in both cohorts for the US, Germany, and Spain (Table 4). For Canada, total costs were lower for abatacept in cohort 2. For all countries, the highest cost saving was seen in cohort 2. The main driver for this was the lower incremental drug cost for patients in cohort 2.

Costs per outcome

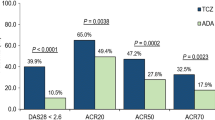

The incremental monthly cost per responding patient and per remitting patient (abatacept–adalimumab) are reported Fig. 1. For cohort 1, all incremental costs per additional health gain were in favour of abatacept in all the countries, except for DAS28-CRP remission in Canada. In cohort 2, most results also favoured abatacept; however, when considering the Canadian model, ACR20 and ACR50 response, and DAS28-CRP and SDAI remission were in favour of adalimumab. Cost savings were generally greater in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA (cohort 1) compared to less severe patients (cohort 2). In addition, cost savings were greater when more stringent response criteria were applied (ACR20 vs ACR90) in both cohorts 1 and 2.

One-way sensitivity analyses

The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses showed that, across all countries and both cohorts, the unit cost of abatacept and adalimumab were the two most influential parameters. Increasing the unit cost of abatacept or decreasing the unit cost of adalimumab resulted in abatacept no longer being cost saving relative to adalimumab.

Additional analyses: indirect costs

Results for the additional analyses incorporating indirect costs are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 2. As expected, total costs increase for both arms across both cohorts (Table 4). Total indirect costs were higher for abatacept compared with adalimumab in both cohorts. This was due to a greater proportion of patients in the more severe HAQ-DI categories (which are associated with higher societal costs) in the abatacept arm than in the adalimumab arm at 2 years. As in the base case, total costs for abatacept were lower in both cohorts for the US, Germany, and Spain. For Canada, total costs were lower for abatacept only in cohort 2.

For cohort 1, all incremental total costs per additional health gain were consistent with the base case and favoured abatacept in all countries except for DAS28-CRP remission in Canada. In cohort 2, whilst most of the results continued to favour abatacept in the US, Germany, and Spain, results for Canada became less consistent with most of the endpoints favouring adalimumab.

Discussion

The current study was performed to evaluate the cost per response and per patient in remission for abatacept relative to adalimumab, both in combination with methotrexate, in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada.

In our base case (excluding indirect costs), the cost per responder favoured abatacept in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA (cohort 1) across all countries. The cost per DAS28-CRP, CDAI, and SDAI remission also favoured abatacept in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA in all countries, except for DAS28-CRP in Canada. The differing result in Canada can be explained by the similarity in the price of abatacept and adalimumab seen in Canada—in all other countries, abatacept is less expensive than adalimumab. This is supported by the results of the one-way sensitivity analyses where changes in the relative costs of abatacept and adalimumab had the largest impact on the model results. Cost savings versus adalimumab were greater in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA (cohort 1) compared to less severe patients (cohort 2) and when more stringent response criteria were applied (cohorts 1 and 2).

When indirect costs were included, the cost per responder and cost per CDAI and SDAI remission continued to favour abatacept in cohort 1 across all countries. However, in cohort 2, results were less consistent, with more outcomes favouring adalimumab when compared with the base case.

Patients with seropositive, erosive early RA have the poorest prognosis making it important to treat these patients promptly with biologic agents [13]. We have demonstrated that, in this patient population, the use of abatacept can be cost saving compared with adalimumab irrespective of the inclusion or exclusion of indirect costs and the countries explored.

The current analysis did not consider the lower cost of biosimilar adalimumab as it was not available across all markets at the time of study. Although the price differential between branded abatacept and biosimilar adalimumab is expected to be lower, we anticipate that the cost per patient in clinical response/remission in seropositive, erosive early RA patients will remain in favour of abatacept.

Limitations pertaining to our updated analysis relate to the post hoc nature and limited sample size for patients with seropositive, erosive early RA from the AMPLE trial used to update the clinical inputs. Nonetheless, this post hoc analysis allowed us to include disease duration ≤ 6 months in the definition of early RA in line with the 2015 ACR criteria [6].

A further limitation relates to our use of data from the AMPLE trial, as it is known that patients treated within a randomized-controlled trial may not necessarily reflect patients treated in the real world. In addition, whilst the AMPLE trial was a multi-national study (including sites in the US and Canada), there may be possible variations in the applicability of the results to Germany and Spain.

Finally, for the calculation of indirect costs in the US, Spain, and Canada, data from a study in Swedish patients [33] were used as it was the only source found linking HAQ-DI response levels with indirect costs. Whilst every attempt was made to correct for differences in currency and the timing of the Swedish study by Kobelt et al., there may be fundamental differences in the indirect costs between patients in the US, Spain, and Canada.

With the increasing number of expensive biologic treatment options, it is becoming increasingly important to be able to identify the subgroups of patients in which treatments are particularly cost-effective. Patients with seropositive, erosive early RA are an important group to target when looking to reduce the budget impact of biologic treatments.

The cost per responder and patient in remission favoured abatacept in patients with seropositive, erosive early RA across all countries. Cost savings were greater in this patient population with poor prognosis and when more stringent response criteria were applied. In this patient population, the use of abatacept instead of adalimumab can lead to lower costs in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada.

References

Scott DL, Wolfe F (2010) Huizinga TWJ rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 376(9746):1094–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60826-4

Gabriel SE (2008) Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 121(10 Suppl 1):S9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.011

Charles-Schoeman C (2012) Cardiovascular disease and rheumatoid arthritis: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep 14(5):455–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-012-0271-5

Lundkvist J, Kastang F, Kobelt G (2008) The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ 8(Suppl 2):S49–60

Furneri G, Mantovani LG, Belisari A, Mosca M, Cristiani M, Bellelli S, Cortesi PA, Turchetti G (2012) Systematic literature review on economic implications and pharmacoeconomic issues of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30(4 Suppl 73):S72–84

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Vaysbrot E, McNaughton C, Osani M, Shmerling RH, Curtis JR, Furst DE, Parks D, Kavanaugh A, O’Dell J, King C, Leong A, Matteson EL, Schousboe JT, Drevlow B, Ginsberg S, Grober J, St Clair EW, Tindall E, Miller AS, McAlindon T (2016) 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 68(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39480 (Epub 32015 Nov 39486)

Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, Nam J, Ramiro S (2017) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 76(6):960–977. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, Katz LM, Lightfoot R Jr, Paulus H, Strand V et al (1995) American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 38(6):727–735

Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL (1995) Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 38(1):44–48

Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA (1993) Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol 20(3):557–560

Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Elegbe A, Maldonado M, Fleischmann R (2014) Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):86–94. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203843 (Epub 202013 Aug 203820)

Fleischmann RWM, Ahmad H et al (2017) SAT0041 Efficacy of abatacept versus adalimumab in patients with seropositive, erosive early ra: analysis of a randomized controlled clinical trial (AMPLE). Ann Rheum Dis 76:782–783

Combe B, Landewe R, Daien CI, Hua C, Aletaha D, Álvaro-Gracia JM, Bakkers M, Brodin N, Burmester GR, Codreanu C, Conway R, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Fonseca J, Raza K, Silva-Fernández L, Smolen JS, Skingle D, Szekanecz Z, Kvien TK, van der Helm-van Mil A, van Vollenhoven R (2016) 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210602

Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, Curtis JR, Bathon JM, St Clair EW, Bridges SL Jr, Zhang J, McVie T, Howard G, van der Heijde D, Cofield SS, Investigators T (2012) A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the treatment of early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis trial. Arthritis Rheum 64(9):2824–2835. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34498

Huizinga TW, Machold KP, Breedveld FC, Lipsky PE, Smolen JS (2002) Criteria for early rheumatoid arthritis: from Bayes’ law revisited to new thoughts on pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum 46(5):1155–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10195

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, Ronday HK, Han KH, Westedt ML, Gerards AH, van Groenendael JH, Lems WF, van Krugten MV, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA (2005) Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 52(11):3381–3390. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21405

Soderlin MK, Bergman S, Group BS (2011) Absent “Window of Opportunity” in smokers with short disease duration. Data from BARFOT, a multicenter study of early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 38(10):2160–2168. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100991

Gremese E, Salaffi F, Bosello SL, Ciapetti A, Bobbio-Pallavicini F, Caporali R, Ferraccioli G (2013) Very early rheumatoid arthritis as a predictor of remission: a multicentre real life prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 72(6):858–862. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201456

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, Kvien TK, Navarro-Compan MV, Oliver S, Schoels M, Scholte-Voshaar M, Stamm T, Stoffer M, Takeuchi T, Aletaha D, Andreu JL, Aringer M, Bergman M, Betteridge N, Bijlsma H, Burkhardt H, Cardiel M, Combe B, Durez P, Fonseca JE, Gibofsky A, Gomez-Reino JJ, Graninger W, Hannonen P, Haraoui B, Kouloumas M, Landewe R, Martin-Mola E, Nash P, Ostergaard M, Ostor A, Richards P, Sokka-Isler T, Thorne C, Tzioufas AG, van Vollenhoven R, de Wit M, van der Heijde D (2016) Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 75(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524

van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza K, van der Woude D, Knevel R, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil AH (2010) Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 62(12):3537–3546. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27692

Weijers L, Baerwald C, Mennini FS, Rodríguez-Heredia JM, Bergman MJ, Choquette D, Herrmann KH, Attinà G, Nappi C, Merino SJ, Patel C, Mtibaa M, Foo J (2017) Cost per response for abatacept versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis by ACPA subgroups in Germany, Italy, Spain, US and Canada. Rheumatol Int 37(7):1111–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3739-9

Cost–Consequence Analysis (2008). In: Kirch W (ed) Encyclopedia of public health. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 168–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_582

Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Zhao C, Maldonado M, Fleischmann R (2013) Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 65(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.37711

Sokolove J, Schiff M, Fleischmann R, Weinblatt ME, Connolly SE, Johnsen A, Zhu J, Maldonado MA, Patel S, Robinson WH (2016) Impact of baseline anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-2 antibody concentration on efficacy outcomes following treatment with subcutaneous abatacept or adalimumab: 2-year results from the AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 75(4):709

First Databank AnalySource® (2015). http://www.fdbhealth.com/solutions/analysource-premier-drug-pricing-services/. Accessed August 2015

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017) CPI detailed reports. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/detailed-reports/home.htm. Accessed March 2018

Taxe L (2017). http://www.lauer-fischer.de/LF/default.aspx?path=WEBAPO-InfoSystem/WEBAPO-Infosystem. Accessed February 2017

The Spanish General Council of Official Colleges of Pharmacists (2015) Medicines database elaborated by the General Council of Pharmacists (Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos Catálogo de Medicamentos). http://www.botplusweb.portalfarma.com. Accessed June 2016

Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (2015). http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/normalizacion/clasifEnferm/home.htm. Accessed December 2015

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad (2015). http://www.msssi.gob.es. Accessed December 2015

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Exceptional Access Program (2018). http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/odbf/odbf_except_access.aspx. Accessed March 2018

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary (2018). http://www.formulary.health.gov.on.ca/formulary/detail.xhtml?drugId=02258595. Accessed March 2018

Kobelt G, Lindgren P, Lindroth Y, Jacobson L, Eberhardt K (2005) Modelling the effect of function and disease activity on costs and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 44(9):1169–1175. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh703

Huscher D, Mittendorf T, von Hinuber U, Kotter I, Hoese G, Pfafflin A, Bischoff S, Zink A (2015) Evolution of cost structures in rheumatoid arthritis over the past decade. Ann Rheum Dis 74(4):738–745. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204311

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Evo Alemao for initiating and overseeing the project. Kirsten Herrmann assisted with the collection and validation of input data for Germany. Mondher Mtibaa assisted with the collection and validation of input data for Canada. Jason Foo, Chaienna Morel, Alexander Marshall, and Carlos Polanco-Sánchez were involved in data collection. Jason Foo and Chaienna Morel were involved in data analysis and interpretation and drafting the article. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jason Foo and Chaienna Morel have served as consultants to Bristol-Myers Squibb. Martin Bergman has received consulting and speaking fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, Celgene, Genentech, Amgen, Janssen, Pfizer, and Novartis. He is a shareholder of JNJ. Christoph Baerwald received honorarium for lectures and consultancies from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, Medac, MSD, Pfizer, and Roche. José Manuel Rodríguez-Heredia has received consulting and speaking fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Roche, Janssen, Gebro, and Novartis. Alexander Marshall, Carlos Polanco-Sánchez, and Roelien Postema are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Foo, J., Morel, C., Bergman, M. et al. Cost per response for abatacept versus adalimumab in patients with seropositive, erosive early rheumatoid arthritis in the US, Germany, Spain, and Canada. Rheumatol Int 39, 1621–1630 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04352-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04352-2