Abstract

DNA damage response includes DNA repair, nucleotide metabolism and even a control of cell fates including differentiation, cell death pathway or some combination of these. The responses to DNA damage differ from species to species. Here we aim to delineate the checkpoint pathway in the dimorphic fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces japonicus, where DNA damage can trigger a differentiation pathway that is a switch from a bidirectional yeast growth mode to an apical hyphal growth mode, and the switching is regulated via a checkpoint kinase, Chk1. This Chk1-dependent switch to hyphal growth is activated with even low doses of agents that damage DNA; therefore, we reasoned that this switch may depend on other genes orthologous to the components of the classical Sz. pombe Chk1-dependent DNA checkpoint pathway. As an initial test of this hypothesis, we assessed the effects of mutations in Sz. japonicus orthologs of Sz. pombe checkpoint genes on this switch from bidirectional to hyphal growth. The same set of DNA checkpoint genes was confirmed in Sz. japonicus. We tested the effect of each DNA checkpoint mutants on hyphal differentiation by DNA damage. We found that the Sz. japonicus hyphal differentiation pathway was dependent on Sz. japonicus orthologs of Sz. pombe checkpoint genes—SP rad3, SP rad26, SP rad9, SP rad1, SP rad24, SP rad25, SP crb2, and SP chk1—that function in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, but was not dependent on orthologs of two Sz. pombe genes—SP cds1 or SP mrc1—that function in the DNA replication checkpoint pathway. These findings indicated that although the role of each component of the DNA damage checkpoint and DNA replication checkpoint is mostly same between the two fission yeasts, the DNA damage checkpoint was the only pathway that governed DNA damage-dependent hyphal growth. We also examined whether DNA damage checkpoint signaling engaged in functional crosstalk with other hyphal differentiation pathways because hyphal differentiation can also be triggered by nutritional stress. Here, we discovered genetic interactions that indicated that the cAMP pathway engaged in crosstalk with Chk1-dependent signaling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

DNA damage causes cells to activate various molecular pathways and induces various cellular activities, including DNA damage repair, cell death, and even cellular differentiation (Carr 2002; Inomata et al. 2009; Wahl and Carr 2001). These responses are regulated or affected by DNA damage responsive (DDR) pathways, and one of these critical pathways is the DNA checkpoint pathway, which is a signaling cascade associated with intensive phosphorylation (Carr 2002). Proteins involved in this checkpoint pathway are evolutionally conserved among many eukaryotes, including between yeast and humans. The molecular functions and structures of these proteins were initially discovered via studies of yeast cells (al-Khodairy et al. 1994; Carr 2002; Weinert and Hartwell 1988). In the fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), a central role of the DNA checkpoint response is carried out by the SPRad3ATR–SPRad26ATRIP kinase complex (SPRad3; human ATR {Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3 related} ortholog in Sz. pombe, SPRad26; human ATRIP {ATR interacting protein} ortholog in Sz. pombe) which phosphorylates various DDR proteins as well as other checkpoint proteins (Carr 1997; Edwards et al. 1999; Enoch et al. 1992). Among the downstream components of this checkpoint pathway, either SPCds1CHK2 or SPChk1CHK1 is phosphorylated and activated by SPRad3ATR in response to a stalled DNA replication fork stall or damaged DNA structure, respectively (Lindsay et al. 1998; Murakami and Okayama 1995; Walworth and Bernards 1996). The activation of either of these effector kinases requires mediator proteins; specifically, activation of SPCds1CHK2 requires SPMrc1Claspin, and activation of SPChk1CHK1 requires SPCrb253BP1 (Alcasabas et al. 2001; Griffiths et al. 1995; Saka et al. 1997; Tanaka and Russell 2001). Furthermore, signaling between SPRad3ATR and effector kinases requires the SPRad17RAD17–SPRfc and the SPRad9RAD9–SPRad1RAD1–SPHus1HUS1 (9-1-1) complexes and the SPCut5TOPBP1 protein, which associates with Rad9RAD9, to play a key role as an activator of SPRad3ATR (Caspari et al. 2000; Furuya et al. 2004; Griffiths et al. 1995; Saka et al. 1997). There are actually slight differences in the configuration of the biological function of effector kinases in other organisms. In vertebrates, CHK1 is activated upon DNA replication fork stalling, and CHK2 is activated upon breakage of double-stranded DNA (Guo et al. 2000; Kumagai and Dunphy 2000; Matsuoka et al. 1998). In the budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), the ortholog of SPCds1CHK2 is SCRad53; this Sc. cerevisiae protein is activated upon both DNA replication stress and DNA damage and is essential for most of the DNA checkpoint pathways (Allen et al. 1994; Weinert et al. 1994). Moreover, ATR, the vertebrate ortholog of Sz. pombe SPRad3, differs in function from SPRad3 because ATM has a major role in the response to double-stranded DNA breaks and because activation of ATM (AtaxiaTelangiectasia-mutated) leads to CHK2 activation (Matsuoka et al. 1998). In contrast, Tel1ATM, the ortholog of ATM in Sz. pombe and Sc. cerevisiae, has a minor role in activating effector kinases (Morrow et al. 1995; Naito et al. 1998). This difference between these yeast species and vertebrate species may be due to differences in the manner in which double-stranded DNA breaks are processed in these taxa because, in the yeasts, these breaks are quickly processed into single-stranded DNA. This newly formed single-stranded DNA would be immediately covered with single-stranded DNA binding protein RPA (Replication Protein A), which can accommodate ATR-ATRIP orthologs, and lead to the activation of the checkpoints (Zou and Elledge 2003).

Checkpoint activation prevents entry into M-phase, which is triggered by activation of Cdk (Cyclin-Dependent Kinase). Cdk sits downstream of the checkpoint pathway, and importantly, inhibitory phosphorylation on tyrosine 15 (Y15) of Cdk is the final target of the checkpoint cascade (Enoch et al. 1991). The regulation on Y15 phosphorylation is conducted by kinases and phosphatases that are placed downstream of the checkpoint pathway (Dunphy and Kumagai 1991; Featherstone and Russell 1991; Gould et al. 1990; Lundgren et al. 1991; Parker et al. 1991; Strausfeld et al. 1991). In case of Sz. pombe, the SPWee1 and SPMik1 kinases phosphorylate Y15, and Cdc25 de-phosphorylates Y15. Mik1, and Cdc25 are targeted either directly or indirectly by the effector-kinases SPChk1CHK1 and SPCds1CHK2, although SPWee1 is controversial for a role in checkpoint response (Christensen et al. 2000; Furnari et al. 1997; Raleigh and O’Connell 2000; Rhind and Russell 1997).

Checkpoint activation can also regulate the mode of cell proliferation. Sz. japonicus is a species of fission yeast. This species undergoes bidirectional growth and symmetrical division (yeast growth) under nutrient-rich conditions, but it switches to unidirectional growth and asymmetrically division (hyphal growth) under certain nutrient conditions (Sipiczki et al. 1998a, b). Upon switching to hyphal growth, the cellular organization of Sz. japonicus changes drastically. Cells develop large vacuoles at the non-growing tips; moreover, they accumulate granular struture at the growing tips (Furuya and Niki 2010). The rate of cell elongation increases and cytokinesis is delayed, consequently, Sz. japonicus forms long multi-cellular hypha during hypal growth. This switch to hyphal growth is also induced following DNA damage, and we demonstrated previously that activation of a Chk1-dependent pathway is necessary and sufficient for development of DNA damage-induced hypha (Furuya and Niki 2010).

Here, we genetically delineated the DNA damage-dependent pathway that leads to hyphal growth. Hyphae were induced via a Sz. pombe-like DNA damage checkpoint pathway and a Rad3ATR–Chk1CHK1-like pathway that included SJ rad3, SJ rad26, SJ rad1, SJ rad9, SJ crb2, SJ chk1, SJ rad24, and SJ rad25 orthologs in Sz. japonicus. Interestingly, the DNA damage-dependent hyphal pathway apparently engaged in crosstalk with the nutrition-dependent hyphal pathway because cAMP inhibited DNA damage-dependent hypha, and cAMP seemed to act upstream of Chk1 kinase.

Materials and methods

Media

Schizosaccharomyces japonicus cells were cultivated as previously described (Furuya and Niki 2009). YE (yeast extract 5 g, glucose 30 g/l) was used as rich media. To induce growth of nutrient-dependent hypha, ME (malt extract 30 g, agar 20 g/l) and YEMA (Yeast extract 5 g, malt extract 30 g, glucose 10 g, agar 20 g/l) were used. A final concentration of 2 % agar was added to make solid media. CPT (camptothecin, Sigma) was used to induce DNA damage-dependent hyphae. For marker selection in YE media, 40 μg/ml of geneticin was used. EMM-2 media was used for the minimal media and the composition was reported previously in Furuya and Niki 2009.

Strains

Strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1. Transformation of plasmids into yeast cells was performed by electroporation (Furuya and Niki 2009). Checkpoint genes in Sz. pombe are well-characterized, the Sz. japonicus orthologs of the Sz. pombe genes were identified by searching the database available at the Broad Institute. (http://www.broadinstitute.org//annotation/genome/schizosaccharomyces_group/MultiHome.html) (Rhind et al. 2011). These Sz. japonicus genes were, crb2; SJAG_0562, cds1; SJAG_04287.4, mrc1; SJAG_04671.4 (Furuya et al. 2012), rad3; SJAG_05420.4 and rad26; SJAG_00429.4, rad1; SJAG_02771.4, tel1; SJAG_06238.4, rad24; SJAG_05886.4 and rad25; SJAG_02576.4. The gene-disruption mutants for each of these Sz. japonicus genes were constructed as described previously (Furuya and Niki 2009).

Results

DNA damage checkpoint pathway, but not DNA replication checkpoint pathway was required for the DNA damage-induced hypha

DNA damage-dependent hypha in Sz. japonicus are induced via activation of SJChk1, and disruption of the auto-inhibitory domain at the C-terminus region of SJChk1 is sufficient for the induction of hypha (Furuya and Niki 2010). However, a similar mutation in Sz. pombe, the cousin fission yeast, does not induce a checkpoint-dependent cell cycle delay (Tapia-Alveal et al. 2009). This phenotypic difference indicates that hyphal induction in Sz. japonicus is a distinct response from cell cycle delay in Sz. pombe and that hyphal induction in Sz. japonicus requires lower cellular SJChk1 activity than does cell cycle delay in Sz. pombe. Thus, we investigated whether DNA damage-dependent hyphal induction required any or all of the orthologs of the components in the DNA damage-dependent chk1-pathway that leads to cell cycle delay in Sz. pombe.

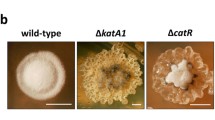

In Sz. pombe, a set of checkpoint components is required to activate SP chk1-dependent cell cycle delay, and some of these components are assembled into distinct complexes. These components include SPRad3ATR and SPRad26ATRIP, which compose the ATR kinase complex; additionally, the checkpoint clamp complex (CCC) comprises SPRad9RAD9, SPRad1RAD1 and SPHus1HUS1 and functions as a DNA damage sensor complex (al-Khodairy et al. 1994; Carr 2002; Caspari et al. 2000; Edwards et al. 1999). Additionally, the mediator protein SPCrb253BP1 is specifically required to activate SPChk1CHK1 (Alcasabas et al. 2001; Griffiths et al. 1995; Saka et al. 1997; Tanaka and Russell 2001). A single ortholog of each of these Sz. pombe genes was present in the Sz. japonicus genome (see the “Materials and methods” section); we generated gene-disruption mutants in each of these Sz. japonicus genes. We also generated gene-disruption mutants in the Sz. japonicus orthologous of SP mrc1 and SP cds1, which are Sz. pombe gene specifically involved in the DNA replication checkpoint. We then asked whether any of these Sz. japonicus genes were required for development of DNA damage-induced hypha. To induce hypha, cells were grown on YE agar media that contained CPT, an inhibitor of topoisomerase I, and incubated for 3 days. Wild-type cells and SJ mrc1 or SJ cds1 mutant cells formed colonies with hypha (Fig. 1). In contrast, cells carrying a SJ rad3, SJ rad26, SJ rad1, SJ rad9, or SJ crb2 mutation failed to form hypha (Fig. 1, Table 2). Thus, we concluded that the “DNA damage checkpoint genes”, but not the “DNA replication checkpoint genes”, were required for hyphal induction.

Requirement of DNA damage checkpoint genes for the DNA damage-stress-dependent hypha formation. cds1::nat and mrc1::nat colonies, but not other checkpoint mutant colonies, can present hypha when growing on YE agar media that contains camptothecin (CPT, 0.2 μM). Colonies were grown for 4 days and the photographed on the 4th day. The phenotypes of single mutant strains were summarized shown in Table 1

Distinct usage of 14-3-3 genes on DNA damage-dependent hyphal pathway from DNA damage checkpoint cell cycle arrest pathway

We extended the analysis further and examined mutations in Sz. japonicas orthologs of 14-3-3 proteins. 14-3-3 proteins function as homo- or hetero-dimeric complexes, and they participate in cell cycle regulation in response to DNA damage or nutritional stress and during cytokinesis (van Heusden 2009). In Sz. pombe, two genes—SP rad24 and SP rad25—encode 14-3-3 proteins, and SP rad24, but not SP rad25, has a significant role in the DNA damage response, including in activation of the DNA damage checkpoint (Ford et al. 1994). Sz. japonicus also possess two 14-3-3 genes that are homologous to the Sz. pombe 14-3-3 genes. Perhaps interestingly, the SJ rad24::nat or the SJ rad25::nat mutation drastically weakened CPT-dependent hyphal induction in Sz. japonicus. Development of hyphal colonies was completely abolished by the SJ rad24::nat mutation when cells were grown on agar plates, and it was greatly diminished by the SJ rad25::nat mutation (Fig. 1). Similarly, most of the mutant cells (either SJ rad24::nat or SJ rad25::nat cells) grown in liquid media retained a yeast-like form, and typical hyphal morphology, such as vacuole-induction, was largely absent from these cells (Fig. 2a).

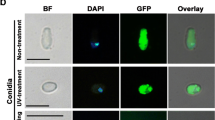

Requirement of DNA damage checkpoint genes, rad24 or rad25, for the DNA damage-stress-dependent hypha formation. a Wild-type, rad24::nat, or rad25::nat cells were cultured in liquid YE media that contained CPT (0.2 μM) to assess hyphal induction. Cells were incubated at 30 °C for 6 h. Scale bar; 10 μm. b chk1-hyp and chk1-hyp rad24::nat colonies were grown at 30 °C on YE agar media to activate the chk1-hyp gene, which carried gain-of-function mutation

The function of SJ rad24 gene was further assessed by ectopic expression experiment of SJChk1. In Sz. pombe, upon DNA damage, SPRad24 acts either on SPChk1 or the downstream effectors of SPChk1. Overexpression of the SP chk1 gene in Sz. pombe leads to cell death with un-attenuated checkpoint arrest, and this lethal phenotype was only compromised in SP rad24 deletion mutants, but not in other checkpoint-defective rad mutants (Ford et al. 1994). Here, we confirmed that SJ rad24 mutations had similar effects in Sz. japonicus. The expression of partially active form of SJChk1 (chk1-hyp) in Sz. japonicus induces hyphal growth even in the absence of genotoxic stress (Furuya and Niki 2010), and we hypothesized that the SJ rad24 deletion mutation should compromise the effect of SJChk1-Hyp activation. As expected, while a SJ chk1-hyp mutant generated extensive hypha at 30 °C, a double mutant carrying SJ chk1-hyp and rad24::nat mutations generated many fewer hypha than the SJ chk1-hyp mutant (Fig. 2b). Notably, SJ rad9::kanMX6 or SJ crb2::kanMX6 mutations did not compromise hyphal induction in SJ chk1-hyp mutants grown at 30 °C ((Furuya and Niki 2010), data not shown). Thus, the DNA damage-dependent hyphal pathway in Sz. japonicus was largely comparable to DNA damage checkpoint pathway in Sz. pombe, except that, in Sz. japonicus, both 14-3-3 genes (SJ rad24 and SJ rad25) have important role in inducing hypha.

Epistatic analysis on Sz. japonicus checkpoint genes

We next examined cell growth upon treatment with agents that damage DNA. The Sz. japonicus checkpoint genes seem to have the same division of labor as do the Sz. pombe checkpoint genes (Table 2). Indeed, both the SJ crb2::kanMX6 mutants and the SJ chk1::kanMX6 mutants showed moderate sensitivity to hydroxyurea (HU; an inhibitor of ribonucleotide-reductase) and to CPT in colony formation assays on solid agar media (Fig. 3a). A double mutant carrying SJ crb2::kam and SJ chk1::nat behaved similarly to each single mutant (i.e., SJ crb2::kanMX6 mutants and SJ chk1::kanMX6 mutants); this finding indicated these two genes have mostly, if not entirely, overlapping functions.

Analysis of epistatic interactions among mutants of DNA damage checkpoint genes in Sz. japonicus. Growth of colonies was compared under camptothecin (CPT) or hydroxyurea (HU) exposure. The leftmost spot contained approximately 6,000 cells when spotted; the spots to the right each represent tenfold serial dilutions; all cells were grown on YE plate that contained indicated reagents. The colonies were grown at 30 °C and photographed at 4th day. The growth of, a wild-type (WT) vs. crb2::kanMX6, chk1::kanMX6, chk1::kanMX6 crb2::kanMX6 cells, b WT vs. cds1::nat, mrc1::nat, cds1::nat mrc1::nat cells, c WT vs. chk1::kanMX6, cds1::nat chk1::kanMX6, cds1::nat mrc1::nat and rad3::kanMX6 cells, d WT vs. chk1::kanMX6, rad3::kanMX6 and rad26::kanMX6 cells, and e WT vs. chk1::kanMX6 and rad9::kanMX6 cells

In Sz. pombe, both single mutants (i.e., SP cds1::nat or SP mrc1::nat) and the double mutant (i.e.SP cds1::nat and SP mrc1::nat) each showed severe sensitivity to HU; this finding indicates that these genes are each required for maintaining the integrity of the DNA replication fork (Alcasabas et al. 2001; Lindsay et al. 1998; Tanaka and Russell 2001). Cells in these three mutant Sz. japonicus strains showed similar colony forming abilities on plates containing HU to one another; this observation indicated that the SJ cds1 and SJ mrc1 genes function within the same pathway (Fig. 3b). In contrast, SJ mrc1::nat mutants were more sensitive to CPT than were SJ cds1::nat mutants (Fig. 3b); moreover, the double mutants (SJ cds1::nat, SJ mrc1::nat cells) were not more sensitive to CPT than were the SJ mrc1::nat single mutants. This result indicated that SJ mrc1 had another role, in addition to associating with SJCds1CHK2 kinase, in the DNA damage response.

SPRad3ATR–SPRad26ATRIP is a central Sz. pombe kinase complex that has a key role in both the DNA damage checkpoint and the DNA replication checkpoint. Consistent with this notion, a SJ rad3::kanMX6 mutation and a SJ rad26::kanMX6 mutation caused Sz. japonicus cells to be highly sensitive to CPT and to HU when cells were grown on agar media (Fig. 3c, d). The sensitivity was severer than that cause by SJ cds1::nat, SJ chk1::kanMX6 double mutations or SJ chk1::kanMX6, SJ mrc1::nat double mutations (Fig. 3c). These findings indicated that, as in other eukaryotes, the SJRad3ATR–SJRad26ATRIP complex in Sz. japonicus had at least one function in addition to its role in activating checkpoint effector-kinase complexes (Enoch et al. 1992; Matsuura et al. 1999). Indeed, the SJ rad3::kanMX6 mutants and the SJ rad26::kanMX6 mutants showed slow growth even without genotoxic insult. The growth defect in Sz. pombe SP rad3 mutants is partially suppressed by disruption of the SP spd1 gene, which is the homologue of ribonucleotide-reductase inhibitor (Liu et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 1998). In fact, introduction of the SJ spd1::nat mutation into a SJ rad3::kanMX6 strain of Sz. japonicus improved cell growth; at 30 °C, the doubling time of wild-type cells was 105 min, that of SJ rad3::kanMX6 cells was 152 min, and that of SJ rad3::kanMX6 spd1::nat cells was 139 min.

Failure to keep replication fork integrity can lead to hyphal induction

CPT causes replicative stress that can alter DNA replication fork structure (Koster et al. 2007; Ray Chaudhuri et al.). In contrast, HU reduces the cellular pool of deoxy-ribonucleotides; consequently, DNA replication forks often stall in cells treated with HU (Lindsay et al. 1998; Lopes et al. 2001). Once the integrity of the replication fork is compromised, the DNA damage checkpoint pathway is activated. Upon exposure to 10 mM HU, wild-type Sz. japonicus cells switched to hyphal growth (Fig. 4a), but lower HU concentrations did not cause this switch (Fig. 4a, b, d). Upon prolonged exposure to HU, replication forks may collapse and this collapse may generate DNA damage-like structures; these structures, rather than stalled replication forks, may induce the switch to hyphal growth. Indeed, HU-dependent hyphal induction was dependent on SJ chk1, but not on SJ cds1 (Fig. 4a, b).

Ectopic activation of hyphal pathway in mutants of checkpoint genes. a Prolonged exposure to hydroxyurea HU induces hypha in wild-type colonies (WT), and this HU-mediated induction was diminished in chk1::kanMX6 colonies. Cells were spread onto YE plates containing 10 mM of HU and then incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. b cds1::nat colonies present hypha when incubated on media containing a low concentration of HU (2 mM), but WT colonies did not. c Growth was compared between cells incubated on camptothecin (CPT) vs. on hydroxyurea (HU). WT, chk1::kanMX6, and tel1::kanMX6 cells were compared. d tel1::kanMX6 colonies present hypha when incubated on media containing a low concentration of HU (5 mM), but WT colonies did not

The integrity of stalled forks was maintained through the activity of the replication checkpoint that is governed by SJCds1CHK2 kinase. Consistently, the switch to hyphal growth occurred at lower HU concentrations for SJ cds1::nat mutants than for wild-type cells (Fig. 4b); this difference was likely due to DNA damage-like structures, which were detected by SJChk1, that resulted from DNA replication fork collapse in the mutants, but not in the wild-type cells (Boddy et al. 1998; Lindsay et al. 1998).

HU-induced hyphae were also elicited via a defect in SJTel1ATM. The tel1 genes in yeasts encode kinases homologous to Rad3ATR. In yeasts, unlike Rad3ATR, which has a major role in the DNA damage response, Tel1ATM has a minor contribution to the resistance to DNA damage. However, Tel1ATM can phosphorylate various checkpoint proteins, and it is involved in double-stranded DNA break repair; these observations indicate that Tel1ATM may participate in efficient DNA damage response (D’Amours and Jackson 2001; Furuya et al. 2004; Nakada et al. 2003; Usui et al. 2001; Zhao et al. 2003). The Sz. japonicus ortholog of SJ tel1 was deleted, and these mutant cells were tested for sensitivity to HU and to CPT. The SJ tel1::kanMX6 mutants did not show obvious sensitivity to HU or CPT (Fig. 4c). However, the mutants did exhibit ectopic induction of hypha at the lower concentration of HU (5 mM) (Fig. 4d); this observation indicated that Sz. japonicus SJ tel1 has a role in genome maintenance at stressed replication forks.

Crosstalk between DNA damage-dependent and nutritional stress-dependent hyphal regulation

DNA damage stress and nutritional stress both induce hyphal differentiation. The cellular morphology of hypha induced by DNA damage stress was indistinguishable from that of hypha induced by nutritional stress. Thus, we assumed that the signals derived from the different stress responses could converge onto the same hyphal regulator. If so, these two stress responses (i.e., the DNA damage stress response and the nutritional stress response) could affect hyphal induction synergistically. Therefore, we compared temperature-dependent hyphal induction in SJ chk1-hyp mutants under several nutrient conditions. The SJ chk1-hyp mutants induced hypha at low temperatures even in the absence of DNA damage stress; moreover, when grown on the nutrient-rich agar media (YE media), the mutants formed hyphal colonies at 30 °C (Fig. 5a). Indeed, SJChk1-dependent hyphal induction was enhanced when the mutants were grown on EMM-2 medium at 30 °C; these growth conditions impose nutrient stress. Furthermore, on the nutrient-poor media (EMM-2), SJ chk1-hyp mutant could induce hypha at a higher temperature; 33 °C (Fig. 5a). Hyphal colonies usually invade the agar and become resistant to being washed off plates by flowing water (Furuya and Niki 2010) (Supplementary Figure 1). As expected, when SJ chk1-hyp cells were spotted and incubated on EMM-2 agar versus YE agar media, more cells remained in the EMM-2 agar after plates were washed with flowing water.

The nutrient stress signal could affect DNA damage-dependent hypha. a Hyphal formation in chk1-hyp mutants was compared between cells grown on YE vs. EMM-2 media. On YE agar media, chk1-hyp induced hypha at 30 °C, but on EMM-2 agar media, the transgene induced hypha at 33 °C. The colonies were grown at the indicated temperature for 3 days and then photographed on the 3rd day. b cAMP inhibited CPT-induced hypha formation, but did not affect chk1-hyp dependent hypha on agar media (bar; 5 mm) c cAMP (50 mM) inhibited CPT-induced hypha formation in wild-type cells grown in liquid media (bar; 10 μm). 0.2 μM of CPT was used

cAMP diminished CPT-induced hypha, but not chk-hyp induced hypha

Induction of hypha by SJ chk1-was enhanced when SJ chk1-hyp cells were switched from YE medium to EMM-2 medium. In Sz. pombe, switching from YE medium to EMM-2 medium correlates with the repression of cAMP-dependent signaling (Yamashita et al. 1996). Thus, we speculated that an increase in the concentration of cellular cAMP could inhibit hyphal induction. Indeed, CPT-induced hypha was inhibited by 50 mM of cAMP (Fig. 5b, c). Reportedly, cAMP reverts nutrient-dependent hyphal growth to yeast growth (Sipiczki et al. 1998b). Thus, we initially thought that the common hypha-regulator that could sit downstream of both DNA damage- and nutrient-stress signaling was repressed by cAMP. However, perhaps surprisingly, cAMP did not inhibit SJ chk-hyp induced hypha (Fig. 5b); this finding indicated that cAMP could act at upstream of SJChk1.

Discussion

In this report, we delineated the DNA damage-dependent hyphal pathway in Sz. japonicus, an organism that is included in the fission yeast genus. Based on genomic sequencing information, we know that Sz. japonicus has a set of genes that are orthologous to the Sz. pombe genes that are involved in checkpoint responses (Fig. 6). However, we have previously shown that, in Sz. japonicus, activation of this checkpoint led to a cell fate different from the cell fate adopted by Sz. pombe cells; upon activation of this checkpoint, Sz. japonicus cells begin hyphal differentiation, but Sz. pombe cells enter a cell cycle delay. Importantly, in Sz. japonicus, DNA damage checkpoint-dependent hyphal induction seemed to require lower amount of DNA damage than DNA damage-induced cell cycle delay. This fact prompted us to investigate the precise division of labor among checkpoint genes upon hyphal differentiation. Furthermore, since hypha is also induced upon nutrient changes, we tested whether these hypha pathways, which are activated by different stimuli, could engage in crosstalk (Sipiczki et al. 1998b).

The checkpoint-dependent hyphal pathway. The diagram summarizes the functional relationship between genes involved in stress response and hyphal induction in Sz. japonicus and DNA damage checkpoint in Sz. pombe. The groups of proteins involved in hyphal induction are shaded in gray and the pathways to activate hypha are indicated by black arrows. The genes indicated in bold have been shown to be required in DNA damage-dependent hyphal induction (this study or Furuya and Niki 2010). Those orthologous genes involved in DNA damage hypha are required in DNA damage checkpoint in Sz. pombe

DNA damage checkpoint pathway in Sz. pombe is equivalent to DNA damage hyphal pathway in Sz. japonicus

We compared the division of labor among the checkpoint genes by constructing gene-disruption mutants for checkpoint genes and asked whether the genes are required for DNA damage-dependent hyphal differentiation. DNA damaged-induced hyphal differentiation in Sz. japonicus required SJ rad3 ATR, SJ rad26 ATRIP, SJ rad9 Rad9, SJ rad1 Rad1, SJ crb2 53BP1, SJ chk1 CHK1, SJ rad24 and SJ rad25. These genes are the Sz. japonicus counterparts of genes that encode proteins in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway of Sz. pombe. In contrast, Sz. japonicus SJ mrc1 Claspin and SJ cds1 CHK2, the counterparts of components of the Sz. pombe DNA replication checkpoint, were not required for hyphal differentiation. Thus, Sz. japonicus had the same series of checkpoint components as does Sz. pombe (Carr 2002). In other words, the DNA damage checkpoint pathway in Sz. pombe corresponded to the DNA damage hyphal pathway in Sz. japonicus.

Cooperation of two 14-3-3 genes at hyphal induction

In fission yeast, two genes (rad24 and rad25) encode 14-3-3 proteins. In Sz. pombe, induction of the DNA damage-dependent checkpoint is mainly dependent on one 14-3-3 gene, SP rad24. However, Sz. pombe cells with a SP rad24 null mutation do undergo partial checkpoint-induced arrest; therefore, SP rad25 might have a partially overlapping role in this checkpoint. Originally in Sz. pombe, SP rad25 was isolated as a multi-copy suppressor of a SP rad24 deletion mutant. Although a single deletion mutant of SP rad25 is not defective in DNA damage response, it is synthetic lethal with SP rad24 deletion mutant (Ford et al. 1994). Interestingly, we found that the Sz. japonicus SJ rad24 and SJ rad25 genes both had a role in the induction of DNA damage-dependent hypha. The SJ rad24 deletion mutant completely abolished hyphal induction when Sz. japonicus cells were grown on agar plate. However, colonies from the SJ rad25 deletion mutant strain seemed to have a residual, but greatly diminished, ability to form the hypha when exposed to DNA damaging agents. Furthermore, few of the SJ rad24-null cells or the SJ rad25-null cells developed typical hyphae with an elongated, vacuole-rich morphology in liquid culture. In Sz. japonicus, the two 14-3-3 proteins could act on different steps of hyphal induction and concomitant regulation may enable the cells to form multi-cellular hypha upon DNA damage response.

Utilization of each 14-3-3 protein is likely to depend on context. Wild-type Sz. japonicus cells form hypha under prolonged incubation on agar media where nutrients are limited. In this study, we used a synthetic minimal media, EMM-2. In this case, hypha development was diminished for SJ rad25 deletion mutants, but not for SJ rad24 mutants (Supplementary Figure 2A). In contrast, when we used YEMA, where malt extract was a main carbon source, hyphae were formed efficiently even with a SJ rad24 or SJ rad25 deletion mutation (Supplementary Figure 2B). Thus, signals from different stress seems to use different combination of 14-3-3 proteins to reach the hypha-regulator.

14-3-3 proteins bind preferentially to phospho-peptides; thus, 14-3-3 proteins often influence the function of phosphorylated proteins; for example, a 14-3-3 protein can cause a phosphorylated protein to relocate or to increase or decrease protein–protein interactions and thereby adopt a new function. 14-3-3 proteins can bind to many proteins; in case of budding yeast, 4 % of proteins in the cell are potential target of 14-3-3 proteins, and these potential are involved in various aspects of many cellular activities (van Heusden 2009). Some of the known activities that 14-3-3 proteins participate in are (1) activating DNA damage checkpoint, (2) delaying cytokinesis, and (3) promoting sexual development signal (Ford et al. 1994; Kitamura et al. 2001; Mishra et al. 2005); moreover, manipulation of these activities upon extracellular stress can cause cells to adopt the morphology of hyphal cells (i.e., the cells elongate and remain attached even after the completion of septation). Searching for specific targets of each Sz. japonicus 14-3-3 protein may uncover the molecular basis of different hyphal pathways.

Crosstalks between nutrient-stress pathways

Both DNA damage stress and nutrient stress induce hypha in Sz. japonicus. Nutrient stress induced hyphal cells were morphologically indistinguishable under a microscope from those induced by DNA damage. Thus, we speculated that these two pathways might converge onto one regulator of hyphal differentiation. We, at least, speculate that the two pathways might share same components or engage in crosstalk. Here, we demonstrated that nutrient stress could enhance DNA damage-induced hyphal differentiation. Additionally, we presented that cAMP might be a key second messenger in the control of both hyphal induction pathways. Induction of hypha upon nutrient stress is repressed by addition of cAMP, and we showed here that induction of hypha following DNA damage was also inhibited by addition of cAMP. Perhaps interestingly, hypha induced via introduction of an active form of SJ chk1 were not inhibited by cAMP, and this finding may have indicated that cAMP could act upstream of SJ chk1. At present, we do not know how cAMP could affect the DNA damage response; cAMP may affect chromatin regulation that in turn affects global transcription, or cAMP regulation may directly affect the activity of checkpoint proteins.

cAMP level is known to be upregulated under glucose-enriched conditions in eukaryotic cells (Broach 1991; Thevelein 1994). In case of Sz. pombe, synthetic media like EMM-2 could correlate with the downregulation of the cAMP pathway (Yamashita et al. 1996). We speculate that cAMP level could tune the extent of the checkpoint-dependent hyphal differentiation, and we believe that mechanism behind this may involve the molecular crosstalk between two different extracellular stresses; nutrient stress and DNA damage stress.

Conclusion

Here we showed that in Sz. japonicus DNA damage triggers cellular differentiation utilizing the same set of DNA damage checkpoint genes as used by Sz. pombe to promote a cell cycle arrest. In addition, slight differences in the involvement of the cAMP pathway could lead to new insights on the relationship between DNA damage and nutrient stress sensing in these yeasts.

References

Alcasabas AA, Osborn AJ, Bachant J, Hu F, Werler PJ, Bousset K, Furuya K, Diffley JF, Carr AM, Elledge SJ (2001) Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat Cell Biol 3:958–965. doi:10.1038/ncb1101-958

al-Khodairy F, Fotou E, Sheldrick KS, Griffiths DJ, Lehmann AR, Carr AM (1994) Identification and characterization of new elements involved in checkpoint and feedback controls in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell 5:147–160

Allen JB, Zhou Z, Siede W, Friedberg EC, Elledge SJ (1994) The SAD1/RAD53 protein kinase controls multiple checkpoints and DNA damage-induced transcription in yeast. Genes Dev 8:2401–2415. doi:10.1101/gad.8.20.2401

Boddy MN, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P (1998) Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Science 280:909–912. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.909

Broach JR (1991) RAS genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: signal transduction in search of a pathway. Trends Genet 7:28–33. doi:0168-9525(91)90018-L

Carr AM (1997) Control of cell cycle arrest by the Mec1sc/Rad3sp DNA structure checkpoint pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev 7:93–98. doi:S0959-437X(97)80115-3

Carr AM (2002) DNA structure dependent checkpoints as regulators of DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 1:983–994. doi:S1568786402001659

Caspari T, Dahlen M, Kanter-Smoler G, Lindsay HD, Hofmann K, Papadimitriou K, Sunnerhagen P, Carr AM (2000) Characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Hus1: a PCNA-related protein that associates with Rad1 and Rad9. Mol Cell Biol 20:1254–1262. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.4.1254-1262.2000

Christensen PU, Bentley NJ, Martinho RG, Nielsen O, Carr AM (2000) Mik1 levels accumulate in S phase and may mediate an intrinsic link between S phase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:2579–2584. doi:97/6/2579

D’Amours D, Jackson SP (2001) The yeast Xrs2 complex functions in S phase checkpoint regulation. Genes Dev 15:2238–2249. doi:10.1101/gad.208701

Dunphy WG, Kumagai A (1991) The cdc25 protein contains an intrinsic phosphatase activity. Cell 67:189–196. doi:0092-8674(91)90582-J

Edwards RJ, Bentley NJ, Carr AM (1999) A Rad3-Rad26 complex responds to DNA damage independently of other checkpoint proteins. Nat Cell Biol 1:393–398. doi:10.1038/15623

Enoch T, Gould KL, Nurse P (1991) Mitotic checkpoint control in fission yeast. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 56:409–416

Enoch T, Carr AM, Nurse P (1992) Fission yeast genes involved in coupling mitosis to completion of DNA replication. Genes Dev 6:2035–2046. doi:10.1101/gad.6.11.2035

Featherstone C, Russell P (1991) Fission yeast p107wee1 mitotic inhibitor is a tyrosine/serine kinase. Nature 349:808–811. doi:10.1038/349808a0

Ford JC, al-Khodairy F, Fotou E, Sheldrick KS, Griffiths DJ, Carr AM (1994) 14–3-3 protein homologs required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Science 265:533–535

Furnari B, Rhind N, Russell P (1997) Cdc25 mitotic inducer targeted by chk1 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Science 277:1495–1497. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1495

Furuya K, Niki H (2009) Isolation of heterothallic haploid and auxotrophic mutants of Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Yeast 26:221–233. doi:10.1002/yea.1662

Furuya K, Niki H (2010) The DNA damage checkpoint regulates a transition between yeast and hyphal growth in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Mol Cell Biol 30:2909–2917. doi:MCB.00049-10

Furuya K, Poitelea M, Guo L, Caspari T, Carr AM (2004) Chk1 activation requires Rad9 S/TQ-site phosphorylation to promote association with C-terminal BRCT domains of Rad4TOPBP1. Genes Dev 18:1154–1164. doi:10.1101/gad.29110418/10/1154

Furuya K, Aoki K, Niki H (2012) Construction of an insertion marker collection of Sz. japonicus (IMACS) for genetic mapping and a fosmid library covering its genome. Yeast 29:241–249. doi:10.1002/yea.2907

Gould KL, Moreno S, Tonks NK, Nurse P (1990) Complementation of the mitotic activator, p80cdc25, by a human protein-tyrosine phosphatase. Science 250:1573–1576

Griffiths DJ, Barbet NC, McCready S, Lehmann AR, Carr AM (1995) Fission yeast rad17: a homologue of budding yeast RAD24 that shares regions of sequence similarity with DNA polymerase accessory proteins. EMBO J 14:5812–5823

Guo Z, Kumagai A, Wang SX, Dunphy WG (2000) Requirement for Atr in phosphorylation of Chk1 and cell cycle regulation in response to DNA replication blocks and UV-damaged DNA in Xenopus egg extracts. Genes Dev 14:2745–2756. doi:10.1101/gad.842500

Inomata K, Aoto T, Binh NT, Okamoto N, Tanimura S, Wakayama T, Iseki S, Hara E, Masunaga T, Shimizu H, Nishimura EK (2009) Genotoxic stress abrogates renewal of melanocyte stem cells by triggering their differentiation. Cell 137:1088–1099. doi:S0092-8674(09)00374-2

Kitamura K, Katayama S, Dhut S, Sato M, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M, Toda T (2001) Phosphorylation of Mei2 and Ste11 by Pat1 kinase inhibits sexual differentiation via ubiquitin proteolysis and 14–3-3 protein in fission yeast. Dev Cell 1:389–399. doi:S1534-5807(01)00037-5

Koster DA, Palle K, Bot ES, Bjornsti MA, Dekker NH (2007) Antitumour drugs impede DNA uncoiling by topoisomerase I. Nature 448:213–217. doi:nature05938

Kumagai A, Dunphy WG (2000) Claspin, a novel protein required for the activation of Chk1 during a DNA replication checkpoint response in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol Cell 6:839–849. doi:S1097-2765(05)00092-4

Lindsay HD, Griffiths DJ, Edwards RJ, Christensen PU, Murray JM, Osman F, Walworth N, Carr AM (1998) S-phase-specific activation of Cds1 kinase defines a subpathway of the checkpoint response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev 12:382–395

Liu C, Powell KA, Mundt K, Wu L, Carr AM, Caspari T (2003) Cop9/signalosome subunits and Pcu4 regulate ribonucleotide reductase by both checkpoint-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Genes Dev 17:1130–1140. doi:10.1101/gad.1090803U-10908R

Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M (2001) The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412:557–561. doi:10.1038/3508761335087613

Lundgren K, Walworth N, Booher R, Dembski M, Kirschner M, Beach D (1991) mik1 and wee1 cooperate in the inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2. Cell 64:1111–1122. doi:0092-8674(91)90266-2

Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ (1998) Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science 282:1893–1897. doi:10.1126/science.282.5395.1893

Matsuura A, Naito T, Ishikawa F (1999) Genetic control of telomere integrity in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: rad3(+) and tel1(+) are parts of two regulatory networks independent of the downstream protein kinases chk1(+) and cds1(+). Genetics 152:1501–1512

Mishra M, Karagiannis J, Sevugan M, Singh P, Balasubramanian MK (2005) The 14–3-3 protein rad24p modulates function of the cdc14p family phosphatase clp1p/flp1p in fission yeast. Curr Biol 15:1376–1383. doi:S0960-9822(05)00771-2

Morrow DM, Tagle DA, Shiloh Y, Collins FS, Hieter P (1995) TEL1, an S. cerevisiae homolog of the human gene mutated in ataxia telangiectasia, is functionally related to the yeast checkpoint gene MEC1. Cell 82:831–840. doi:0092-8674(95)90480-8

Murakami H, Okayama H (1995) A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature 374:817–819. doi:10.1038/374817a0

Naito T, Matsuura A, Ishikawa F (1998) Circular chromosome formation in a fission yeast mutant defective in two ATM homologues. Nat Genet 20:203–206. doi:10.1038/2517

Nakada D, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K (2003) ATM-related Tel1 associates with double-strand breaks through an Xrs2-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev 17:1957–1962. doi:10.1101/gad.109900317/16/1957

Parker LL, Atherton-Fessler S, Lee MS, Ogg S, Falk JL, Swenson KI, Piwnica-Worms H (1991) Cyclin promotes the tyrosine phosphorylation of p34cdc2 in a wee1 + dependent manner. EMBO J 10:1255–1263

Raleigh JM, O’Connell MJ (2000) The G(2) DNA damage checkpoint targets both Wee1 and Cdc25. J Cell Sci 113(Pt 10):1727–1736

Ray Chaudhuri A, Hashimoto Y, Herrador R, Neelsen KJ, Fachinetti D, Bermejo R, Cocito A, Costanzo V, Lopes M Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:417–423. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2258

Rhind N, Chen Z, Yassour M, Thompson DA, Haas BJ, Habib N, Wapinski I, Roy S, Lin MF, Heiman DI, Young SK, Furuya K, Guo Y, Pidoux A, Chen HM, Robbertse B, Goldberg JM, Aoki K, Bayne EH, Berlin AM, Desjardins CA, Dobbs E, Dukaj L, Fan L, FitzGerald MG, French C, Gujja S, Hansen K, Keifenheim D, Levin JZ, Mosher RA, Muller CA, Pfiffner J, Priest M, Russ C, Smialowska A, Swoboda P, Sykes SM, Vaughn M, Vengrova S, Yoder R, Zeng Q, Allshire R, Baulcombe D, Birren BW, Brown W, Ekwall K, Kellis M, Leatherwood J, Levin H, Margalit H, Martienssen R, Nieduszynski CA, Spatafora JW, Friedman N, Dalgaard JZ, Baumann P, Niki H, Regev A, Nusbaum C (2011) Comparative functional genomics of the fission yeasts. Science 332:930–936

Rhind N, Russell P (1997) Roles of the mitotic inhibitors Wee1 and Mik1 in the G(2) DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Mol Cell Biol 21:1499–1508. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.5.1499-1508.2001

Saka Y, Esashi F, Matsusaka T, Mochida S, Yanagida M (1997) Damage and replication checkpoint control in fission yeast is ensured by interactions of Crb2, a protein with BRCT motif, with Cut5 and Chk1. Genes Dev 11:3387–3400. doi:10.1101/gad.11.24.3387

Sipiczki M, Takeo K, Grallert A (1998a) Growth polarity transitions in a dimorphic fission yeast. Microbiology 144(Pt 12):3475–3485. doi:10.1099/00221287-144-12-3475

Sipiczki M, Takeo K, Yamaguchi M, Yoshida S, Miklos I (1998b) Environmentally controlled dimorphic cycle in a fission yeast. Microbiology 144(Pt 5):1319–1330. doi:10.1099/00221287-144-5-1319

Strausfeld U, Labbe JC, Fesquet D, Cavadore JC, Picard A, Sadhu K, Russell P, Doree M (1991) Dephosphorylation and activation of a p34cdc2/cyclin B complex in vitro by human CDC25 protein. Nature 351:242–245. doi:10.1038/351242a0

Tanaka K, Russell P (2001) Mrc1 channels the DNA replication arrest signal to checkpoint kinase Cds1. Nat Cell Biol 3:966–972. doi:10.1038/ncb1101-966ncb1101-966

Tapia-Alveal C, Calonge TM, O’Connell MJ (2009) Regulation of chk1. Cell Div 4:8. doi:1747-1028-4-8

Thevelein JM (1994) Signal transduction in yeast. Yeast 10:1753–1790

Usui T, Ogawa H, Petrini JH (2001) A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol Cell 7:1255–1266. doi:S1097-2765(01)00270-2

van Heusden GP (2009) 14–3-3 Proteins: insights from genome-wide studies in yeast. Genomics 94:287–293. doi:S0888-7543(09)00159-110.1016/j.ygeno.2009.07.004

Wahl GM, Carr AM (2001) The evolution of diverse biological responses to DNA damage: insights from yeast and p53. Nat Cell Biol 3:E277–E286. doi:10.1038/ncb1201-e277

Walworth NC, Bernards R (1996) rad-dependent response of the chk1-encoded protein kinase at the DNA damage checkpoint. Science 271:353–356

Weinert TA, Hartwell LH (1988) The RAD9 gene controls the cell cycle response to DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 241:317–322

Weinert TA, Kiser GL, Hartwell LH (1994) Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev 8:652–665

Yamashita YM, Nakaseko Y, Samejima I, Kumada K, Yamada H, Michaelson D, Yanagida M (1996) 20S cyclosome complex formation and proteolytic activity inhibited by the cAMP/PKA pathway. Nature 384:276–279. doi:10.1038/384276a0

Zhao X, Muller EG, Rothstein R (1998) A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol Cell 2:329–340. doi:S1097-2765(00)80277-4

Zhao H, Tanaka K, Nogochi E, Nogochi C, Russell P (2003) Replication checkpoint protein Mrc1 is regulated by Rad3 and Tel1 in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 23:8395–8403. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.22.8395-8403.2003

Zou L, Elledge SJ (2003) Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300:1542–1548. doi:10.1126/science.1083430300/5625/1542

Acknowledgments

We thank Nanayo Ishihara, Takako Tsugata and Manami Kuruma for technical assistance, and all members of the Niki lab for helpful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (K.F.).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. S. Hoffman.

To distinguish genes and gene products in two species of fission yeast, we appropriately add the prefix SP for Sz. pombe, or SJ for Sz. japonicus to them.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

294_2012_384_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Figure 1 Hypha that were induced by the chk1-hyp mutation become more resistant to washing when grown on EMM-2 agar media. Wild-type (WT) or chk1-hyp cells were spotted onto YE or EMM-2 agar media and incubated for 4 days at the respective temperatures. After the colony growth, agar plates were washed with flowing water. (PDF 79 kb)

294_2012_384_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Figure 2 Wild type or rad24::nat or rad25::nat cells were spotted on A. EMM-2 or B. YEMA agar media; the ability these cells to form hypha was assessed. Plates were incubated at 33 ℃ for 5 days and then photographed on the 5th day. (PDF 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Furuya, K., Niki, H. Hyphal differentiation induced via a DNA damage checkpoint-dependent pathway engaged in crosstalk with nutrient stress signaling in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus . Curr Genet 58, 291–303 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-012-0384-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-012-0384-4