Abstract

Intestinal microbiota is an important prognostic factor for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), but its role in predicting survival has not been determined. Here, stool samples at day 15 ± 1 posttransplant were obtained from 209 patients at two centers. Microbiota was examined using 16S rRNA sequencing. The microbiota diversity and abundance of specific bacteria (including Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae) were assigned a value of 0 or 1 depending on whether they were positive or negative associated with survival, respectively. An accumulated intestinal microbiota (AIM) score was generated, and patients were divided into low- and high-score groups. A low score was associated with a better 3-year cumulative overall survival (OS) as well as lower mortality than a high score (88.5 vs. 43.9% and 7.1 vs. 35.8%, respectively; both P < 0.001). In multivariate analysis, a high score was found to be an independent risk factor for OS and transplant-related mortality (hazard ratio = 5.68 and 3.92, respectively; P < 0.001 and 0.003, respectively). Furthermore, the AIM score could serve as a predictor for survival (area under receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.836, P < 0.001). Therefore, the intestinal microbiota score at neutrophil recovery could predict survival following allo-HSCT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a curative option for hematological malignancies. Complications such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and infections remain major causes of death beyond malignancy relapse, limiting the application of allo-HSCT [1, 2].

Increasing studies have demonstrated that the intestinal microbiome plays an important role in host physiology during allo-HSCT [3,4,5]. Previous studies have indicated that patients undergoing allo-HSCT easily suffer from microbiota injury owing to the use of antibiotic agents and conditioning [3, 4, 6]. We and others have reported that the microbiota disruption caused by allo-HSCT is characterized by expansions in pathogenic bacteria and loss of diversity, a variable that reflects the number of unique bacterial taxa present and their relative frequencies [4, 5, 7]. Diversity of the intestinal microbiota has previously been correlated with GVHD, infection, relapse, and toxic effects on organs. Importantly, loss of diversity is associated with transplant- and GVHD-related mortality [3, 4, 8]. Recently, a study has shown that intestinal microbiota diversity, which is associated with mortality, is a biomarker for predicting survival. However, it is unclear which bacteria are closely associated with survival. For example, a study indicated that Enterococcus expansion was associated with GVHD and mortality [9], while another study showed that loss of Blautia was associated with mortality [10]. Therefore, a divergence of the relationships exists between microbiota and outcomes of allo-HSCT, and identifying the bacteria that could predict survival is essential.

Furthermore, it is necessary to confirm whether these bacteria together could serve as prognostic predictors for survival. In this study, we prospectively obtained stool samples from patients undergoing allo-HSCT on day 15 ± 1 posttransplantation. The relationship between microbiota and survival was further estimated, and a microbiota score derived from the combination of diversity and several specific bacteria was developed, which could suitably predict survival after allo-HSCT.

Methods

Subjects and samples

We performed a retrospective analysis of a prospective study recruiting allo-HSCT recipients from the Nanfang Hospital and The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University between January 2016 and December 2018. Stool samples were collected from patients at approximately day 15 ± 1 posttransplantation. The samples were labeled and stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction [4, 7]. If the period between collection and disposition was longer than 6 h, the samples were discarded. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, and The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China. After approval of the study by the ethics committee, consent from the participants was obtained for biospecimen collection and analysis. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis

The conditioning regimens used in this study included two standard myeloablative regimens (busulfan + cyclophosphamide (BuCY) and total body irradiation + CY (TBI + CY)) and a sequential intensified regimen (fludarabine + Ara-C plus TBI + Cy + etoposide) as previously described [7, 11, 12]. Conditioning selection was based on disease type and status at transplantation. Generally, patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission (CR) were given BuCY, those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in CR were given TBI + CY, and those in non-CR were administered the intensified regimen. In addition, some high-risk patients received the intensified regimen [7, 11, 12].

Cyclosporin A (CsA) plus methotrexate (MTX) (on days + 1, + 3, + 6) was administered to patients who underwent a matched sibling donor (MSD) transplant for GVHD prophylaxis. CsA + MTX + thymoglobulin (ATG; Genzyme, Cambridge) was used for patients who underwent a matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplant for GVHD. The CsA + MTX + ATG + mycophenolate (MMF) combination was administered to patients who underwent haploidentical donor (HID) transplant [7, 11, 12].

Infection prophylaxis and treatment

At our institutions, oral sulfamethoxazole and norfloxacin were administered to all patients for infection prophylaxis [11, 12]. Ganciclovir was administered for the prophylaxis or treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, whereas acyclovir was used for other viruses. Antifungal agents were prescribed for prophylaxis against fungal infections. Fluconazole (0.3 g/day) or itraconazole (0.4 g/kg/day) was used until 60 days posttransplantation for patients with no history of invasive fungal infection (IFI), while those with a history of IFI were given voriconazole (0.4 g/day), itraconazole (0.4 g/day), caspofungin (50 mg/day), or ambisome (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) intravenously. Oral voriconazole or itraconazole was prescribed as a substitute for intravenous (i.v) treatment when the peripheral white blood cell count was greater than 2.0 × 10^9/L and discontinued after 90 days posttransplantation.

Among antibiotics, carbapenems (imipenem or meropenem) combined with amikacin were administered as first-line antibiotics for patients developing fever during neutropenia. Vancomycin or piperacillin/tazobactam was used as the second-line antibiotic treatment. Other antibiotics were administered variably and to a minority of patients. For example, tigecycline was occasionally used for bacterial infections caused after administration of noneffective second-line antibiotics.

Sequencing of 16S rRNA for fecal specimens

DNA from each stool specimen was extracted and purified, and the 16S rRNA gene between the V3 and V4 regions was amplified using PCR with modified universal bacterial primers, as described in our previous reports [7]. Microbiome DNA concentrations were detected using a qPCR assay, and sequencing was performed using the HiSeq2500 PE250 platform [7]. Sequencing data were screened and filtered according to quality and then aligned to the full-length 16S rRNA gene using the SILVA reference alignment as a template. Sequences were assembled into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with 97% similarity [7].

Microbiota analysis

Intestinal microbiota diversity was evaluated using the inverse Simpson index, as well as the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and Shannon index as previously described [4, 7, 13]. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was applied to identify different microbiota characteristics using LEfSe software; the threshold on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features was 2.0 [7]. Phylogenetic classification at the family level was calculated according to a naive Bayesian classification scheme and the Greengenes reference database [4, 7, 14]. In addition, a nonparametric test (Mann–Whitney) was performed to compare the statistical differences between groups.

Clinical metadata and survival prediction

All clinical data, including neutrophil recovery, were collected via retrospective review of clinical characteristics by individuals blinded to the microbiota of the participants. Neutrophil recovery was defined as an absolute neutrophil count was greater than 0.5 × 10^9/L posttransplantation for three consecutive days.

Area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) from logistic regression analysis were used to evaluate the predictive performance of outcomes. The cutoff values of the inverse Simpson index and the selected bacteria were determined through AUC analysis of ROC curves for the predictive survival model by identifying the highest AUC, with a corresponding sensitivity and specificity. Based on the cutoff values for survival, a score of 0 or 1 was assigned for the inverse Simpson index and abundance of each microbial taxon (including Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae), where 0 represented a positive association with survival and 1 indicated a negative association. An accumulated intestinal microbiota (AIM) score was then generated by summing all the values (Table 1) [14,15,16]. Finally, the AIM score for predicting outcomes was determined by estimating the performance of the microbiota. The primary outcomes overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analyzed; additionally, transplant-related mortality (TRM) was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized as median or mean ± SD for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between the intestinal microbiota and groups were analyzed by “heatmap” estimation. The cumulative survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test (Mantel–Haenszel). Considering the competing risks of death and relapse, cumulative incidence curves in a competing risk setting were generated to calculate the probabilities of TRM, acute GVHD (aGVHD), and chronic (cGVHD) using the Gray test [11]. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess survival in multivariate analysis. Variables that were associated with survival (P < 0.20) in univariate analysis were included in the final Cox model. All P-values were considered two sided with a significance level of 0.05. SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago), or R software (version 3.1.1) was used to analyze all data [17], and P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics and bacterial selection

From the original cohort of 240 patients, 31 patients were excluded due to death before sample collection (n = 4) and unsuccessful fecal examination (n = 27) (Fig. 1). A total of 209 patients from the cohort were included in this study. We selected bacteria that had a significant negative or positive correlation with survival, as previously mentioned. Through AUC analysis of ROC plots for survival, the inverse Simpson index and abundance of four bacterial families, including Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae, were determined (AUC ≥ 0.70 and P < 0.01), and others showing an AUC < 0.70 or P ≥ 0.01 were excluded. The results demonstrated that the AUCs of diversity and abundance of the four aforementioned bacterial families were 0.766, 0.751, 0.708, 0.800, and 0.703, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.615 and 0.774, 0.590 and 0.849, 0.615 and 0.774, 0.686 and 0.736, and 0.609 and 0.811 for OS, respectively (Fig. 2). Based on cutoff values for survival, an AIM score was then generated from the assigned score for the diversity and abundance of the four bacterial families by adding all values (Table 1). The subjects were divided into low-score (0–3; n = 132) and high-score (4–5; n = 77) groups based on the AIM score (Tables 1 and 2).

The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2. Most of the transplant characteristics were similar between the two groups, such as donor gender, underlying disease and poor-risk genetics, graft source, and bloodstream infection. However, the high-score group included more patients who received an HLA mismatched (4/10–5/10 mismatched) donor transplant, β-lactam antibiotics (including carbapenems and piperacillin/tazobactam), or vancomycin (i.v.) than the low-score group (P = 0.017, 0.002, and 0.017, respectively); additionally, the number of patients with a non-CR status at transplant and who underwent intensified conditioning was higher in the high-score group than that in the low-score group (P = 0.025 and < 0.001, respectively; Table 2). No other variables were found to be significantly different between the groups (P > 0.05).

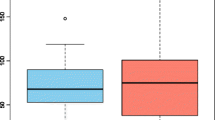

Intestinal microbiota characteristics at neutrophil recovery

Although no difference was found between the low- and high-score groups before transplantation (pr-conditioning) (OTUs, 61 vs. 62; Shannon index, 1.91 vs. 1.89; P = 0.935 and 0.780, respectively, Fig. S1A and B), the number of OTUs and the Shannon index of microbiota diversity were higher in the low-score group than that in the high-score group (44.0 vs. 22.0, 1.83 vs. 0.66, respectively, both P < 0.001, Fig. S2A and B). To investigate enrichment differences in microbiota between the two groups, heatmap and LEfSe analyses were performed. We focused on the abundant bacterial families and compared their relative abundances between the two groups. The heatmap shows the abundance and phylogenetic composition of each subject in the two groups (Fig. 3A). In Fig. 3A, the transition from gray to red indicates the increase in microbiota abundance. The microbial abundance in the stool was higher in the low-score group than that in the high-score group (Fig. 3A). LEfSe analysis demonstrated that the enriched bacteria were significantly different between the groups (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Akkermansiaceae, and Streptococcaceae were enriched in the low-score group, whereas Enterobacteriaceae, Aeromonadaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Moraxellaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Staphylococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Burkholderiaceae were enriched in the high-score group (Fig. 3B).

As expected, other bacteria were different between the low- and high-score groups, for example, Bacteroidaceae and Porphyromonadaceae (38.846 vs. 0.006%, 1.135 vs. 0.000%, respectively, all P < 0.001), consistent with the results of LEfSe analysis, as shown in Fig. 3B. Taken together, patients with low and high scores showed significantly distinct intestinal microbiota.

We also explored the correlations between the single parameters of the AIM score (Fig. S3). The reverse Simpson index was positively associated with the abundance of Lachnospiraceae (r = 0.60, P < 0.001) and negatively associated with the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae (r = − 0.42, P < 0.001). The abundance of Enterobacteriaceae was negatively correlated with that of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae (r = − 0.32 and − 0.26, respectively, both P < 0.001, Fig. S3).

GVHD

The median time of aGVHD emergence was day 21 (10–64) posttransplantation. The overall cumulative incidences of grades II-IV aGVHD by day + 100 posttransplant were 33.3% (29.2–37.4%) and 63.6% (58.1–69.1%) for the low- and high-score groups, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. S4A). The cumulative incidences of grade III-IV aGVHD were 6.1% (4.1–8.2%) and 32.5% (27.2–37.8%) for the low- and high-score groups, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. S4B). With regard to the correlation between AIM score and aGVHD severity, Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation (r = 0.397, P < 0.001). As for single-organ manifestations, of the 93 patients with grades II-IV aGVHD, 79, 72, and 31 experienced skin, intestinal, and hepatic aGVHD symptoms, respectively, and these organ manifestations were also correlated with the AIM score (r = 0.243, 0.487, and 0.345, respectively, all P < 0.001).

For the low- and high-score groups, the overall 3-year cumulative incidence of cGVHD posttransplantation was 38.8% (34.3–43.3%) and 30.0% (23.5–36.5%), respectively (P = 0.709, Fig. S4C), and that of extensive cGVHD was 11.9% (9.0–14.8%) and 11.4% (7.3–15.5%), respectively (P = 0.843, Fig. S4D).

Survival and TRM

The median follow-up was 19.0 months (range: 1.9–36 months). Based solely on the reverse Simpson index and the abundance of the four bacterial families, the 3-year cumulative OS was significantly different between each group with high and low index (or abundance) (all P < 0.001, Fig. S5A-E). The 3-year cumulative OS based on the AIM score posttransplantation was 88.5% (85.2–91.8%) and 43.9% (37.9–49.9%) for the low- and high-score groups, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 4A). The 3-year cumulative DFS posttransplantation was 78.9% (75.1–82.7%) and 39.3% (33.2–45.4%) for the low- and high-score groups, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B).

The accumulated intestinal microbiota (AIM) score and its association with survival. Both the 3-year cumulative overall survival (OS, A) and the disease-free survival (DFS, B) were longer in the low-score than those in the high-score group. C The 3-year cumulative transplant-related mortality (TRM) was considerably lower in the low-score group than that in the high-score group

A total of 53 patients died at a median of 7.0 months (range: 1.6–19.0 months) during follow-up, and the causes of death included TRM (n = 33) and relapse (n = 20). Of the 33 patients who died of TRM, infection (n = 16, including 1 Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder) was the main cause of TRM. Other causes of death included aGVHD (n = 7), cGVHD (n = 3), intracranial hemorrhage (n = 1), hepatic veno-occlusive disease (n = 1), hemorrhagic cystitis (n = 1), thrombotic microangiopathy (n = 1), and multiple organ failure (n = 2), but the cause of death of 1 patient was unknown. The distribution of reasons for death between the two groups is shown in Table S1. The cumulative TRM is shown in Fig. 4C. The 3-year cumulative TRM posttransplantation was 7.1% (4.6–9.6%) and 35.8% (29.8–41.8%) for the low- and high-score groups, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C).

Risk factors for survival and TRM

In multivariate analysis (Table 3), III-IV aGVHD, high AIM score, poor risk, and non-CR status during transplantation were independent risk factors for OS (hazard ratio [HR] = 4.95, 5.68, 1.62, and 1.84; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.60–9.42, 2.75–11.71, 1.14–2.31, and 1.00–3.38; P < 0.001, < 0.001, = 0.007, and 0.048, respectively). No other factors, including patient age, female donor, 4/10–5/10 HLA-mismatched donor, β-lactam administration, or conditioning intensity, were significantly associated with OS in multivariate analysis (all P > 0.05), although female donors, HLA-mismatched donors, and intensified conditioning were risk factors in univariate analysis (P = 0.015, 0.019, and 0.008, respectively). For DFS, poor-risk, non-CR status during transplantation, grades III-IV aGVHD, and high AIM scores were the independent risk factors (HR = 1.57, 2.23, 3.12, and 3.04; 95% CI: 1.18–2.10, 1.31–3.81, 1.74–5.60, and 1.74–5.31; P = 0.002, 0.003, < 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively). For TRM, III-IV aGVHD and high AIM scores were the independent risk factors (HR = 7.60 and 3.92; 95% CI: 3.43–16.83 and 1.57–9.79; P < 0.001 and = 0.003, respectively). Female donor, intensified conditioning, blood stream infection, and β-lactam administration were not identified as independent risk factors (all P > 0.05), although they were associated with TRM in univariate analysis (P = 0.002, 0.002, 0.015, and 0.009, respectively). Meanwhile, patient age, genetic risk, HLA mismatch, graft source, and administration of vancomycin were not associated with TRM (all P > 0.05).

Microbiota survival prediction

To better explore the potential clinical effects of the microbiota markers, the inverse Simpson index and the abundance of Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae were scored based on the cutoff values for survival. Subsequently, the AIM score for survival was calculated. The result of the ROC curve analysis for the predictive model indicated that the AIM score could serve as a predictor for survival (AUC = 0.836, P < 0.001; cutoff value, 3.5), with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.842 and 0.809, respectively (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we compared the AUC of the AIM score with that of the five factors and found that the AUC of the AIM score was higher than that of the inverse Simpson index as well as Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae abundance (P = 0.004, < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, respectively), although the AUC of Erysipelotrichaceae abundance was not significantly different from that of the AIM (P = 0.152). In addition, we could not identify that one factor was more important for the prediction than the other (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The relationship between intestinal microbiota and survival has gained increasing attention in recent years [4, 18, 19]. Taur Y et al. [4] observed that a low intestinal microbiota diversity was positively correlated with worse survival. Peled JU [8] reported that profound microbiota injury, that is, loss of diversity and domination by a single taxon, was associated with mortality. In this study, we found that loss of Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae in addition to diversity and a bloom of Enterobacteriaceae in patients undergoing allo-HSCT at neutrophil recovery was associated with poor survival, and that the cumulative AIM score from these four bacteria taxa and diversity could predict survival.

Previous studies have demonstrated that low microbiota diversity is associated with allo-HSCT complications, such as infections and aGVHD, which, at least in part, leads to poor survival [3, 8, 20, 21]. A few studies have indicated that intestinal microbiota could be a predictor of mortality during allo-HSCT [4, 8, 22]. However, studies on specific bacteria and their roles in predicting survival and mortality are inconsistent. A previous study indicated that Gammaproteobacteria is associated with mortality [4]. Recently, a study suggested that Enterococcus could be a predictor of ravaged microbiota and poor prognosis after allo-HSCT [23].

This study mainly focused on determining whether specific microbiota is a biomarker for survival. First, our results demonstrated that both the diversity and abundance of microbiota were positively (Lachnospiraceae) or negatively (Enterobacteriaceae) correlated with survival, and the microbiota score was associated with aGVHD occurrence. The associations between the microbiota and survival were consistent with those reported in our previous study on microbiota in aGVHD, although the prediction of survival from Peptostreptococcaceae was replaced by Ruminococcaceae due to a lower ROC area [15]. The findings for Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae were in accordance with those reported by Peled JU, and a new finding of a bloom in Enterobacteriaceae that was associated with mortality, which might be attributed to vancomycin administration as described in our previous report [7, 8]. Second, we found that other bacteria, including Bacteroidaceae and Porphyromonadaceae, had a positive association, and Enterococcaceae had a negative association with survival, but the AUC of the latter in survival prediction was less than 0.70 (data not shown). In addition, we observed that the high-score group comprised more patients who received an HLA-mismatched (4/10–5/10 mismatched) donor transplant, and β-lactam antibiotics and vancomycin (i.v.), as well as patients who had a non-CR status at transplantation and underwent intensified conditioning than the low-score group; however, no difference in the microbiota diversity was identified between the groups before transplantation. These findings suggest that different antibiotics, conditioning, and disease status might have multiple effects on the microbiota [7, 15, 17, 24, 25].

Furthermore, this study indicated that microbiota diversity combined with the four bacterial families could serve as a potent predictor of survival. A lower AIM score was associated with better survival and lower transplant-related mortality. Our study indicates that the differentiation of survival based on the AIM score is superior to that of diversity alone. The bacteria of the AIM score in predicting survival were consistent with that in our previous study with regard to aGVHD prediction [15, 17]. Additionally, the intensity of microbiota disruption accompanied TRM at a certain level. The AIM score may be effective and convenient for clinical applications with high sensitivity and specificity. With regard to the mechanism of the association between the four bacteria and survival, studies have demonstrated that Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae can maintain intestinal homeostasis, induce tolerance via their metabolites, and then decrease the occurrence of infection and serious aGVHD [3, 7, 26]. However, the bloom of Enterobacteriaceae is thought to be involved in injury of intestinal mucosa and homeostasis, resulting in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, promotion of occurrence of infectious diseases and GVHD, and an increase in mortality [3, 7, 26].

In multivariate analysis, a high AIM score, which corresponds to serious microbiota disruption, and III-IV aGVHD were independent risk factors for TRM. These results were consistent with those of a recent report in which patients with skewed microbiota displayed a high frequency of posttransplantation mortality [20]. With regard to the effects of the microbiota on the outcome of allo-HSCT, our findings are in accordance with previous studies that have reported mechanisms through which the microbiome modulates alloreactivity [9, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. A limitation of this study is the fact that it was a retrospective analysis, and the sample size was not relatively large; thus, our results should be validated in a larger prospective study.

Conclusions

This study indicated that the intestinal microbiota score could predict survival following allo-HSCT. Our data may guide clinicians to determine the patients who are at serious risk of mortality. Furthermore, the results suggest that these patients should consider and implement interventions to restore the integrity of intestinal microbiota, such as fecal microbiota transplantation or preemptive treatment strategies. Future studies are needed for a more in-depth investigation of the mechanism underlying the microbiota disruption of outcomes; additionally, a larger prospective validation study from multiple centers is essential in the future.

References

Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, Waller EK, Weisdorf DJ, Wingard JR, Cutler CS, Westervelt P, Woolfrey A, Couban S, Ehninger G, Johnston L, Maziarz RT, Pulsipher MA, Porter DL, Mineishi S, McCarty JM, Khan SP, Anderlini P, Bensinger WI, Leitman SF, Rowley SD, Bredeson C, Carter SL, Horowitz MM, Confer DL (2012) Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 367(16):1487–1496. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1203517

Brissot E, Labopin M, Stelljes M, Ehninger G, Schwerdtfeger R, Finke J, Kolb HJ, Ganser A, Schäfer-Eckart K, Zander AR, Bunjes D, Mielke S, Bethge WA, Milpied N, Kalhs P, Blau IW, Kröger N, Vitek A, Gramatzki M, Holler E, Schmid C, Esteve J, Mohty M, Nagler A (2017) Comparison of matched sibling donors versus unrelated donors in allogeneic stem cell transplantation for primary refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a study on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. J Hematol Oncol 10(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-017-0498-8

Shono Y, van den Brink MRM (2018) Gut microbiota injury in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Rev Cancer 18(5):283–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2018.10

Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, No D, Gobourne A, Viale A, Dahi PB, Ponce DM, Barker JN, Giralt S, van den Brink M, Pamer EG (2014) The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 124(7):1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-02-554725

Payen M, Nicolis I, Robin M, Michonneau D, Delannoye J, Mayeur C, Kapel N, Berçot B, Butel MJ, Le Goff J, Socié G, Rousseau C (2020) Functional and phylogenetic alterations in gut microbiome are linked to graft-versus-host disease severity. Blood Adv 4(9):1824–1832. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001531

Weber D, Jenq RR, Peled JU, Taur Y, Hiergeist A, Koestler J, Dettmer K, Weber M, Wolff D, Hahn J, Pamer EG, Herr W, Gessner A, Oefner PJ, van den Brink MRM, Holler E (2017) Microbiota disruption induced by early use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is an independent risk factor of outcome after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 23(5):845–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.02.006

Han L, Jin H, Zhou L, Zhang X, Fan Z, Dai M, Lin Q, Huang F, Xuan L, Zhang H, Liu Q (2018) Intestinal microbiota at engraftment influence acute graft-versus-host disease via the Treg/Th17 balance in allo-HSCT recipients. Front Immunol 9:669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00669

Peled JU, Gomes ALC, Devlin SM, Littmann ER, Taur Y, Sung AD, Weber D, Hashimoto D, Slingerland AE, Slingerland JB, Maloy M, Clurman AG, Stein-Thoeringer CK, Markey KA, Docampo MD, Burgos da Silva M, Khan N, Gessner A, Messina JA, Romero K, Lew MV, Bush A, Bohannon L, Brereton DG, Fontana E, Amoretti LA, Wright RJ, Armijo GK, Shono Y, Sanchez-Escamilla M, Castillo Flores N, Alarcon Tomas A, Lin RJ, Yáñez San Segundo L, Shah GL, Cho C, Scordo M, Politikos I, Hayasaka K, Hasegawa Y, Gyurkocza B, Ponce DM, Barker JN, Perales MA, Giralt SA, Jenq RR, Teshima T, Chao NJ, Holler E, Xavier JB, Pamer EG, van den Brink MRM (2020) Microbiota as predictor of mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 382(9):822–834. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1900623

Stein-Thoeringer CK, Nichols KB, Lazrak A, Docampo MD, Slingerland AE, Slingerland JB, Clurman AG, Armijo G, Gomes ALC, Shono Y, Staffas A, Burgos da Silva M, Devlin SM, Markey KA, Bajic D, Pinedo R, Tsakmaklis A, Littmann ER, Pastore A, Taur Y, Monette S, Arcila ME, Pickard AJ, Maloy M, Wright RJ, Amoretti LA, Fontana E, Pham D, Jamal MA, Weber D, Sung AD, Hashimoto D, Scheid C, Xavier JB, Messina JA, Romero K, Lew M, Bush A, Bohannon L, Hayasaka K, Hasegawa Y, Vehreschild M, Cross JR, Ponce DM, Perales MA, Giralt SA, Jenq RR, Teshima T, Holler E, Chao NJ, Pamer EG, Peled JU, van den Brink MRM (2019) Lactose drives Enterococcus expansion to promote graft-versus-host disease. Science (New York, NY) 366(6469):1143–1149. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3760

Ilett EE, Jørgensen M, Noguera-Julian M, Nørgaard JC, Daugaard G, Helleberg M, Paredes R, Murray DD, Lundgren J, MacPherson C, Reekie J, Sengeløv H (2020) Associations of the gut microbiome and clinical factors with acute GVHD in allogeneic HSCT recipients. Blood Adv 4(22):5797–5809. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002677

Han LJ, Wang Y, Fan ZP, Huang F, Zhou J, Fu YW, Qu H, Xuan L, Xu N, Ye JY, Bian ZL, Song YP, Huang XJ, Liu QF (2017) Haploidentical transplantation compared with matched sibling and unrelated donor transplantation for adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first complete remission. Br J Haematol 179(1):120–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14854

Xuan L, Huang F, Fan Z, Zhou H, Zhang X, Yu G, Zhang Y, Liu C, Sun J, Liu Q (2012) Effects of intensified conditioning on Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol 5:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-5-46

Doki N, Suyama M, Sasajima S, Ota J, Igarashi A, Mimura I, Morita H, Fujioka Y, Sugiyama D, Nishikawa H, Shimazu Y, Suda W, Takeshita K, Atarashi K, Hattori M, Sato E, Watakabe-Inamoto K, Yoshioka K, Najima Y, Kobayashi T, Kakihana K, Takahashi N, Sakamaki H, Honda K, Ohashi K (2017) Clinical impact of pre-transplant gut microbial diversity on outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 96(9):1517–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-3069-8

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF (2009) Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75(23):7537–7541. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01541-09

Han L, Zhang H, Chen S, Zhou L, Li Y, Zhao K, Huang F, Fan Z, Xuan L, Zhang X, Dai M, Lin Q, Jiang Z, Peng J, Jin H, Liu Q (2019) Intestinal microbiota can predict acute graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25(10):1944–1955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.07.006

Zhan X, Sun X, Hong Y, Wang Y, Ding K (2017) Combined detection of preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and CEA as an independent prognostic factor in nonmetastatic patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection is superior to NLR or CEA alone. Biomed Res Int 2017:3809464. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3809464

Han L, Zhao K, Li Y, Han H, Zhou L, Ma P, Fan Z, Sun H, Jin H, Jiang Z, Liu Q, Peng J (2020) A gut microbiota score predicting acute graft-versus-host disease following myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg 20(4):1014–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15654

Noor F, Kaysen A, Wilmes P, Schneider JG (2019) The gut microbiota and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: challenges and potentials. J Innate Immun 11(5):405–415. https://doi.org/10.1159/000492943

Rashidi A, Kaiser T, Graiziger C, Holtan SG, Rehman TU, Weisdorf DJ, Khoruts A, Staley C (2020) Specific gut microbiota changes heralding bloodstream infection and neutropenic fever during intensive chemotherapy. Leukemia 34(1):312–316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0547-0

Kusakabe S, Fukushima K, Maeda T, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Fujita J, Yokota T, Shibayama H, Oritani K, Kanakura Y (2020) Pre- and post-serial metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota as a prognostic factor in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 188(3):438–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16205

Devaux CA, Million M, Raoult D (2020) The butyrogenic and lactic bacteria of the gut microbiota determine the outcome of allogenic hematopoietic cell transplant. Front Microbiol 11:1642. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01642

Mancini N, Greco R, Pasciuta R, Barbanti MC, Pini G, Morrow OB, Morelli M, Vago L, Clementi N, Giglio F, Lupo Stanghellini MT, Forcina A, Infurnari L, Marktel S, Assanelli A, Carrabba M, Bernardi M, Corti C, Burioni R, Peccatori J, Sormani MP, Banfi G, Ciceri F, Clementi M (2017) Enteric microbiome markers as early predictors of clinical outcome in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant: results of a prospective study in adult patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 4(4):ofx215. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx215

Kusakabe S, Fukushima K, Yokota T, Hino A, Fujita J, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Shibayama H, Kanakura Y (2020) Enterococcus: a predictor of ravaged microbiota and poor prognosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26(5):1028–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.019

Yu J, Sun H, Cao W, Han L, Song Y, Wan D, Jiang Z (2020) Applications of gut microbiota in patients with hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Exp Hematol Oncol 9(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-020-00194-y

Weber D, Hiergeist A, Weber M, Dettmer K, Wolff D, Hahn J, Herr W, Gessner A, Holler E (2019) Detrimental effect of broad-spectrum antibiotics on intestinal microbiome diversity in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: lack of commensal sparing antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 68(8):1303–1310. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy711

Fellows R, Denizot J, Stellato C, Cuomo A, Jain P, Stoyanova E, Balázsi S, Hajnády Z, Liebert A, Kazakevych J, Blackburn H, Corrêa RO, Fachi JL, Sato FT, Ribeiro WR, Ferreira CM, Perée H, Spagnuolo M, Mattiuz R, Matolcsi C, Guedes J, Clark J, Veldhoen M, Bonaldi T, Vinolo MAR, Varga-Weisz P (2018) Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat Commun 9(1):105–105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02651-5

Shono Y, Docampo MD, Peled JU, Perobelli SM, Velardi E, Tsai JJ, Slingerland AE, Smith OM, Young LF, Gupta J, Lieberman SR, Jay HV, Ahr KF, Porosnicu Rodriguez KA, Xu K, Calarfiore M, Poeck H, Caballero S, Devlin SM, Rapaport F, Dudakov JA, Hanash AM, Gyurkocza B, Murphy GF, Gomes C, Liu C, Moss EL, Falconer SB, Bhatt AS, Taur Y, Pamer EG, van den Brink MRM, Jenq RR (2016) Increased GVHD-related mortality with broad-spectrum antibiotic use after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in human patients and mice. Sci Transl Med 8(339):339ra71. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2311

Mathewson ND, Jenq R, Mathew AV, Koenigsknecht M, Hanash A, Toubai T, Oravecz-Wilson K, Wu SR, Sun Y, Rossi C, Fujiwara H, Byun J, Shono Y, Lindemans C, Calafiore M, Schmidt TM, Honda K, Young VB, Pennathur S, van den Brink M, Reddy P (2016) Gut microbiome-derived metabolites modulate intestinal epithelial cell damage and mitigate graft-versus-host disease. Nat Immunol 17(5):505–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3400

Jenq RR, Ubeda C, Taur Y, Menezes CC, Khanin R, Dudakov JA, Liu C, West ML, Singer NV, Equinda MJ, Gobourne A, Lipuma L, Young LF, Smith OM, Ghosh A, Hanash AM, Goldberg JD, Aoyama K, Blazar BR, Pamer EG, van den Brink MR (2012) Regulation of intestinal inflammation by microbiota following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med 209(5):903–911. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20112408

Riwes M, Reddy P (2018) Microbial metabolites and graft versus host disease. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg 18(1):23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14443

Wu K, Yuan Y, Yu H, Dai X, Wang S, Sun Z, Wang F, Fei H, Lin Q, Jiang H, Chen T (2020) The gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide aggravates GVHD by inducing M1 macrophage polarization in mice. Blood 136(4):501–515. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019003990

Schluter J, Peled JU, Taylor BP, Markey KA, Smith M, Taur Y, Niehus R, Staffas A, Dai A, Fontana E, Amoretti LA, Wright RJ, Morjaria S, Fenelus M, Pessin MS, Chao NJ, Lew M, Bohannon L, Bush A, Sung AD, Hohl TM, Perales MA, van den Brink MRM, Xavier JB (2020) The gut microbiota is associated with immune cell dynamics in humans. Nature 588(7837):303–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2971-8

Acknowledgements

We thank Lizhi Zhou (PhD, Southern Medical University, Department of Biostatistics, Guangzhou, China) for statistical analysis and critical modification of the manuscript. We are grateful to Mrs. Zhensheng Dong (Beijing Genomics Institute, Shenzhen, China) for analysis of the sequencing data from stool samples as well as the staff of the Beijing Genomics Institute. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Key Research and Development Projects (grant no. 2017YFA0105500, 2017YFA105504), the Jointly Sponsored Project of Henan Medical Science and Technology Research Plan (LHGJ20190040), the Key Scientific Research Projects of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (20B320048), and the Medical Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (SB201901106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LjH, YL, and QfL designed the paper. LjH, HyZ, and YyL wrote the paper. MmZ, JyW, JbH, ZpF, and LnS contributed to the collection of samples and recorded the clinical data. YlL, JfY, and WmW were responsible for DNA extraction and examination of stool samples. PM performed data analysis. WL, HS, and ZxJ assisted in the writing and revision of the manuscript. JP contributed to the analysis in the revised version. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, L., Zhang, H., Ma, P. et al. Intestinal microbiota score could predict survival following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 101, 1283–1294 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-022-04817-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-022-04817-8