Abstract

In recent decades, plant-based sensors have been increasingly used to monitor plant water status, detecting water stress and improving irrigation scheduling. Among these sensors, microtensiometer (MT) continuously measures trunk water potential (TWP) supporting real-time monitoring of TWP and in turn plant water need assessment. However, MT response to environmental stimuli as mediated by plant has not yet fully elucidated. This study reports on a two-year experiment modelling the response of MT-based TWP to changing soil water content (SWC) and air vapor pressure deficit (VPD). During summer time, at a commercial kiwifruit vineyard, vines (n = 63) were differentially irrigated (100%, 50%, 25% of full irrigation need) for ~ 52 days and grouped in CTRL, Mild and Severe, respectively. In two vines per group, the TWP was monitored using MT (20-min interval). Parallel VPD and SWC (× 3 FDR probes) were also recorded. During the experiments drought stressed vines were recovered. Across treatments, soil moisture ranged from approx. 40% to 18%, and the corresponding TWP from approx. – 0.01 to – 1.1 MPa. Results show that a piecewise linear regression model explains the relationship between MT-based TWP and the pressure chamber-based stem water potential (SWP) (R2 = 0.78) showing different slopes when SWP drops below – 1.6 MPa. The response of TWP to changing VPD and SWC was analyzed at daily scale and throughout the season. A model accounting for time-lag between TWP and VPD and for the hysteresis of TWP shows that the diurnal TWP is mostly driven by VPD (R2 = 0.74) in well-irrigated vines. To explain TWP response in Mild and Severe irrigation treatment, the model also included the SWC term achieving R2 = 0.66. Potential application of MT for irrigation management along with some limitations (e.g., long-term durability) are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mediterranean regions are expected to experience and cope with significant increases in temperature and evapotranspiration combined with reduced rainfall, exacerbated by climate change, limiting water availability for crop irrigation and leading to more frequent water stress conditions (Moriondo and Bindi 2007; del Pozo et al. 2019). Various water-saving strategies have been developed to improve water use efficiency in agriculture (Naor 2006). In recent years, many approaches to irrigation scheduling have been proposed based on the measurement of variables related to soil and plant water status (Jones 2004; López-Bernal et al. 2024). Soil sensors measuring volumetric soil water content provide real-time feedback on actual soil moisture (Segovia-Cardozo et al. 2022), allowing the adjustment of irrigation water volumes to real field conditions (Vera et al. 2019; Mininni et al. 2022), and providing information on when to irrigate and how much water to apply (López-Bernal et al. 2024). On the other hand, several methods based on the measurement of plant variables (e.g., maximum daily shrinkage, plant water potential, trunk growth rate) have been considered to identify plant water stress indicators and improve irrigation scheduling (Intrigliolo and Castel 2004; Fernández 2017). However, their practical application is still hindered by the sensitivity of plant water stress indicators to atmospheric demand (López-Bernal et al. 2024) and by limited availability of successful commercial probes (Jones 2004). Measuring plant water status and identifying the threshold of water stress at which plant growth and yield are severely affected, and beyond which irrigation is required (i.e. when to irrigate), has been reported to be crucial for implementing accurate irrigation scheduling (Fernandes-Silva et al. 2018; Ahumada-Orellana et al. 2019). Among the parameters of plant water status, those measuring plant water potential are more rigorous and generally applied (Jones 2004). In particular, leaf water potential (LWP) has been widely recognized as a reliable plant water status indicator (Hsiao 1990) mainly because values measured before dawn are considered the result of the continuous equilibrium achieved overnight between leaves and water content of the soil (Améglio et al. 1999; Santesteban et al. 2019). However, LWP varies rapidly and is extremely environmentally sensitive, so it does not provide an adequate long-term signal of stress (Jones 2007). The water potential of non-transpiring leaves (i.e. stem water potential, SWP) is less affected by evaporative water demand and is therefore a more useful and robust indicator of plant water status (McCutchan and Shackel 1992). SWP, especially that measured at midday, has been reported to be a practical tool for determining the level of water stress experienced by the plant (Intrigliolo and Castel 2006; Shackel 2007). Hence, this might support understanding the physiological response of the plant to limited water conditions (Shackel 2007), and guiding irrigation decisions on a site-specific basis (Shackel et al. 1997; De Swaef et al. 2009; Blanco et al. 2018). However, the same SWP can be exhibited by a plant under wet soil conditions at high vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and by a plant under dry soil conditions at low VPD. A baseline SWP has previously been reported to serve as a plant-based reference for non-limiting soil water conditions, where irrigation is not required (McCutchan and Shackel 1992; Shackel et al. 2021). “Target” SWP has been previously established for plum (Lampinen et al. 2001), almond (Stewart et al. 2011) and grapevine (Williams and Baeza 2007) which need to be considered as the normal range of variation in SWP associated with VPD conditions. Although measurements of SWP and LWP have been performed using the Scholander pressure chamber for years, several limitations for modern precision irrigation emerged. These include the inability to continuously monitor plant water status and various technical limitations, such as the leaf selection process and acclimatization to nullify transpiration, as well as the experience of the technician (Noun et al. 2022). Fulton et al. (2001) proposed modified procedures for measuring SWP to make it a more convenient and practical tool for irrigation management (e.g., equilibration period of 10 min for routine SWP monitoring and irrigation scheduling, sample size of about 10 leaves, and measurement of SWP under midday conditions). However, the capacity to automate plant measurements is valuable for irrigation scheduling (Jones 2007), and microtensiometer (MT) sensors in particular can overcome the limitations of automating direct measurements of plant water status. MT embedded directly in the stem and in contact with the xylem vessels continuously measure the trunk water potential (TWP), providing information on plant water status during the irrigation season (Pagay et al. 2014). Numerous experimental trials have been conducted in pot and field to continuously monitor TWP and validate this technology in various tree species, such as nectarines (Conesa et al. 2023), grapevines (Pagay 2022), apples (Lakso and Intrigliolo 2022; Nieto et al. 2023), pears (Blanco and Kalcsits 2023) and almonds (Lakso et al. 2022a, b).

Several studies provided correlative information linking the TWP measured by MT to midday SWP measured by pressure chamber (Blanco and Kalcsits 2021, 2023) supporting MT as a reliable sensor for continuous measurement of SWP. Hence, the TWP is expected to be driven by environmental variables such as soil moisture and VPD. In line with this, a series of studies analyzed the response of MT to environmental driver(s) such soil moisture (Blanco and Kalcsits 2023), or soil matric potential (Conesa et al. 2023). The relationship between TWP and VPD has been focused on well irrigated trees, showing variable results according to species and cultivars studied (Pagay 2021; Blanco and Kalcsits 2023). Moreover, the VPD has been employed as a driver of plant physiological traits (e.g., transpiration, sap flux) inducing, on a diurnal basis, a typical hysteresis pattern (Zeppel et al. 2004; Bai et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2023). That hysteretic pattern is associated with the time lag existing between VPD and the physiological trait (e.g., Wang et al. 2023). Hence, in order to elucidate the response of TWP to VPD that hysteresis should be accounted for by considering separately its ascending and descending harm (e.g., Amato et al. 2021).

Kiwifruit is known to have high water requirements (Chartzoulakis et al. 1993) and susceptibility to decreasing soil water content (Chartzoulakis et al. 1993; Montanaro et al. 2007; Pratima et al. 2016), both of which can be exacerbated in Mediterranean regions, highlighting the importance of irrigation management. In this scenario, MT can help to detect plant water stress, even temporary, which easily occurs during the hottest hours of the day and is responsible for the midday depression in physiological parameters such as net assimilation rate (Montanaro et al. 2009). Given the lack of studies evaluating the reliability and effectiveness of MT in kiwifruit, the present research evaluated both the functionality and limitations of MT in yellow-fleshed kiwifruit grown under Mediterranean conditions. Therefore, the main objectives of this study were: (a) to investigate MT responses to SWC and VPD variables; (b) to examine the relationship between TWP and SWP.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

The experimental trial was carried out in a commercial and mature kiwifruit vineyard planted in 2014 in Metaponto (South Italy, 40°24'N 16°46'E) during two growing seasons (2021 and 2023). A yellow-fleshed kiwifruit cultivar (A. chinensis var. chinensis cv. ‘Zesy 002’) was grafted onto D1 rootstock (A. chinensis var. deliciosa) and the vines were trained to pergola system at 5 × 2 m planting distance (1000 vines ha−1). The vines were covered with neutral transpiring polyethylene anti-hail netting (monofilaments 0.3 mm in diameter, rectangular hole size of 2.2 × 2.6 mm, approximately 8% shade). The soil consisted of a uniform sandy clay loam texture and its hydrological characteristics, determined through the soil–water retention curve, showed field capacity (FC) at 39.48% (v v−1), wilting point (WP) at 18.49% (v v−1) and the resulting fraction of available water (AW) equal to 20.99% (v v−1).

Experimental design

The experimental plot consisted of 63 plants grouped into three irrigation blocks. During 2021, all vines were well-watered (CTRL) receiving 100% of full irrigation volume (IV), with daily irrigation volumes of approx. 50–60 m3 ha−1.

During the 2023 irrigation season (June-mid-October), starting from the end of July, two irrigation treatments (21 vines each) were imposed to reach different levels of water deficit (Mild and Severe), distributing reduced irrigation volumes relative to CTRL (21 vines) (Fig. S1). The adoption of restricted irrigation covered several days of the experimental period, during which CTRL received daily irrigation volumes of about 60 m3 ha−1 (100% IV), while Mild and Severe treatments received 30–45 m3 ha−1 and 0–15 m3 ha−1, respectively (Table 1). In particular, the Severe treatment underwent two stress periods (DOY 220-DOY 237 and DOY 244-DOY 255) with recovery periods (DOY 238-DOY 243 and DOY 256-DOY 266) during which the Severe treatment received 100% IV.

Further details on timing and fraction of irrigation volumes supplied are reported in Table 1.

Irrigation management

Vines were irrigated by a sprinkler system consisting of a single auto-compensating micro-sprinkler per vine spaced 1 m from the trunk, with a flow rate of 40 L h−1 and a wetting radius of 0.90 m. The three irrigation blocks were equipped with independent valves (solenoid valves with flow rates from 0.23 to 6.8 m3 h−1 and pressures from 1 to 10 bar). An analog and a digital (10–100 L electric pulse−1) flow meters were used to record the irrigation volumes distributed, and an automatic irrigation controller for remote control of water supply (“Irrifarm” system, Pan. Agri s.r.l., Basilicata, Italy).

Irrigation volumes were calculated through a simplified water balance method using the following equation (Mininni et al. 2022):

where: IV was the irrigation volume (m3 ha−1); ETc was the crop evapotranspiration (mm); ER was the effective rainfall (mm), ime was the irrigation method efficiency (0.95). The ER was calculated by considering daily rainfall < 5 mm as ineffective (Dastane 1974). The crop coefficient Kc considered specific for kiwifruit, ranging from 0.5 to 1.1 along the season, was reported in FAO Irrigation and Drainage paper Nr. 66 (Xiloyannis et al. 2012). Irrigation volumes were then adjusted weekly considering the fluctuations of soil moisture at different depths (FDR probes, see below) (Mininni et al. 2022). Soil moisture measurements in the soil volume wetted by irrigation were used to maintain soil water content at values within the readily available water (RAW) defined according to Calabritto et al. (2024). Details on the theoretical (Eq. 1) and real (applied) irrigation volumes are reported in Table 1.

During the 2021, irrigation was managed to ensure non-limiting soil water conditions, maintaining the soil moisture close to FC throughout the day. That volume was split into three/four interventions per day throughout the irrigation season from May to October.

During the 2023 season, all irrigation treatments were irrigated with 100% IV until the beginning of the experimental trial, with daily irrigation volumes of approx. 45–60 m3 ha−1, defined according to the vine’s water needs and soil water content monitoring, split in three/four interventions. During the experimental period, the daily irrigation volumes were split in three/four interventions, except from DOY 220 to DOY 237, from DOY 233 to DOY 237, and from DOY 227 to DOY 237, when irrigation volumes were supplied in only one or two events per day (early in the morning and late in the afternoon) in the CTRL, Mild, and Severe irrigation treatments, respectively. This was done to reduce the effect of daily irrigation volume splitting on plant water status (Puértolas et al. 2020).

Weather variables and soil moisture monitoring

Environmental parameters, such as rainfall, air temperature, and relative humidity were recorded daily and/or hourly by a meteorological station (SKU-6253, Davis Instruments, USA) connected to a wireless data-logger system (Winet S.r.l. Cesena, Italy). These sensors were installed near the experimental orchard block and mounted above the kiwifruit canopy, outside the hail net protection, at about 5 m from the ground. Hourly air vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa) was computed using air temperature and relative humidity (Goudriaan and van Laar 1994). The FAO Penman–Monteith equation was used to quantify reference evapotranspiration (ET0, mm d−1) based on the hourly available climatic data from a regional weather station located at about 1 km from the field. The environmental water deficit refers to the precipitation deficit, which was calculated as the difference between the cumulative monthly values of ET0 and rainfall during both 2021 and 2023 seasons. This deficit compares the amount of water provided by rainfall with the potential water demand (potential evapotranspiration). As a result, values can also be used to characterize the environment and its exposure to drought stress. Frequency Domain Reflectometry (FDR) 90 cm multi-profile soil moisture probes with sensors every 10 cm (SENS-STk90 Drill & Drop, Sentek Sensor Technologies Stepney, Australia) were used to continuously monitor the volumetric soil water content (SWC) throughout the soil vertical profile, detecting instantaneous oscillations in each soil layer every 30 min. The probes were installed on the row at a distance of 0.50 m from the vine stem and approximately in the center of the volume of wet soil. One multi-profile FDR probe per treatment was installed to monitor soil moisture. A soil layer of 0–60 cm was considered in the present study according to Xiloyannis et al. (2023) and Calabritto et al. (2024) based on soil characteristics and root development and uptake activity. SWC values were averaged according to the soil layer considered (sensors at 5, 15 and 25 cm of each probe for the 0–30 cm layer; sensors at 35, 45 and 55 cm of each probe for the 30–60 cm layer). The SWC values were calibrated against gravimetric samples (n = 3) collected across soil moisture range covering that from FC to WP.

Trunk and stem water potential

The TWP of kiwifruit vines was continuously monitored using MT (FloraPulse, Davis, CA, USA) embedded directly in the trunk of kiwifruit vines at 140 cm from ground and inserted at 2 cm depth, ensuring the direct contact with the xylem (Lakso et al. 2022b). The sensors were installed at predawn, when transpiration, xylem flux and VPD are minimal (Améglio et al. 1999; Phillips et al. 1999) ensuring trunk tissues not drying during installation procedure. Sensors were then allowed to equilibrate with the vine xylem within a few days from installation (Pagay 2022). Values of TWP were recorded at 20 min intervals. The sensor unit was connected to a dedicated solar powered wireless data logger. The data were stored in a memory card inserted into the logger and uploaded to a cloud repository accessible through a user interface on the FloraPulse website (FloraPulse Davis, CA, USA). In the 2021 irrigation season, a total of two MT was installed in the field on two vines to monitor TWP when irrigation scheduling was managed to maintain soil moisture close to FC and to preliminarily evaluate MT installation and response in kiwifruit.

In the 2023 irrigation season, six MT were installed in the field on six vines (one sensor per vine), allowing the monitoring of two vines per irrigation treatment (CTRL, Mild and Severe). The TWP values were averaged and referred to the pertaining treatment. The daily maximum oscillation of TWP (ΔTWP) was determined as the difference between the value recorded at pre-dawn (around 3 AM, solar time) when the plant water potential was in equilibrium with soil and the minimum value reached during the day (usually between 1 and 3 PM).

Plant water status was also monitored through the stem water potential (SWP) measured on the same vines equipped with MT in 2023. The SWP was measured on five fully developed, expanded and not-exposed leaves per treatment (one or two leaves per vine) chosen from the middle part of the canopy layer. The selected leaves were wrapped in a thin aluminum foil for about half an hour prior of the measurement, and then excised for immediate SWP measurement with a Scholander pressure chamber (Model 1000, PMS Instrument Company, Corvallis, OR, USA) pressurized with nitrogen according to the procedure recommended by McCutchan and Shackel (1992). The acclimatization time of the leaf was previously defined by evaluating SWP values of various leaves (n = 8) acclimated for different times, defining 30 min as the time needed for stabilizing the stem water potential value (Table S1). Diurnal SWP was measured for 13 days (DOY 224, 226, 229, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 240, 244, 254, 255, 262) during the 2023 experiment at approx. three-hour interval (7:00, 10:00, 13:00, 15:00, and 17:00 h, solar time).

Leaf gas exchange parameters

Photosynthetic (A), stomatal conductance (gsw) and transpiration (E) rates were measured at approx. three-hour interval (7:00, 10:00, 13:00, 15:00, and 17:00 h, solar time) at DOY 237 during 2023 using a portable photosynthesis system Li-Cor 6400 (Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). During leaf gas exchange measurements air temperature, reference CO2 concentration and radiation (Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density, PPFD) were maintained at the prevailing external environmental conditions. Four vines per treatment were chosen for gas exchange measurements by selecting one mature and fully expanded leaf per vine in the outer layer from the middle region of the canopy, with non-exposed leaves from the same region used for SWP measurements.

Modelling trunk water potential and statistical analysis

All paired soil moisture, air VPD (outside the hail net) and TWP data from CTRL, Mild and Severe vines were pooled in a single dataset. In order to account for the diurnal hysteresis response of TWP to VPD (Fig. S2), the dataset was filtered by extracting the raw data occurring within 3 AM and the time corresponding to the lowest TWP in each day. The present modelling analysis also considered the time lag between TWP and VPD (Fig. S3) (Pagay 2022). Hence, the TWP series was shifted backward by 4 h according to the correlation method reported in Wan et al. (2023). Following this, the dataset (n = 1282) was randomly split into testing (30%) and training (70%) fractions. The signal of the MT (TWP, MPa) was modeled as a response variable of a linear model using soil moisture and air VPD as unique driving factors (i.e., Y ~ VPD, Y ~ SWC). The additive (Y ~ VPD + SWC) and interaction (Y ~ VPD + SWC + VPD*SWC) linear models were also examined as nested models of the Y ~ VPD one. Note that the interaction model labeling was simplified as Y ~ VPD*SWC.

The accuracy of each model was assessed through the coefficient of determination (R2), the root mean squared error (RMSE), and the mean absolute error (MAE). The models were then compared through AIC (Sakamoto et al. 1986). Residuals of each single model were calculated as the difference between observed and fitted values; thereafter their randomness and constancy of variance were evaluated and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for further model comparison. The models employing only VPD or SWC as predictor were also fitted to data only referring to well irrigated vines. Correlation between TWP and SWP was performed using a piecewise regression model (β0 + β1Ψi + β2(Ψi − ΨBP)) (Ψi = SWP; ΨBP = SWP at breakpoint) after the Davies’s test testing for the existence of a breakpoint (Priulla and D’Angelo 2024). One-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between irrigation treatments for each physiological parameter, after testing for normality (Shapiro–Wilk's test) and equal variance (Levene's test) hypotheses. Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) was used as a post-hoc test for multiple comparisons of means, with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant. All data analysis and modelling were conducted in R (R Core Team 2021).

Results

Environmental conditions

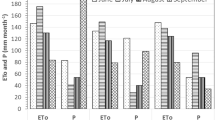

The annual ET0 and rainfall were approx. 1180 mm and 477 mm for the 2021 and 1199 mm and 467 mm for the 2023, respectively (Fig. 1). Hence, the resulting annual environmental water deficit was about 703 and 732 mm in 2021 and 2023, respectively. High evapotranspiration and low rainfall generally occurred during the summer months, contributing to a high environmental water deficit during the irrigation season (April–October) reaching approx. 739 and 688 mm for the 2021 and 2023, respectively (Fig. 1).

Daily crop reference evapotranspiration (ET0), maximum air vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and maximum air temperature (Tmax) during the 2021 and 2023 experimental periods are shown in Fig. 2. Daily maximum air temperatures were variable throughout the experimental trial, reaching maximum values of 39.4 °C (DOY 223) and 38.5 °C (DOY 236) in the 2021 and 2023 seasons, respectively. Air temperature exceeded 30 °C for 25 (2021) and 57 days (2023). Noticeably, air temperature was above 35 °C during 9 and 12 days in the 2021 and 2023 seasons, respectively. Daily maximum VPD values, equal to 4.24 and 5.02 kPa, were achieved on DOY 225 and 236 in the 2021 and 2023, respectively.

Daily reference evapotranspiration (ET0, mm d−1), maximum vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa) and maximum air temperatures (Tmax, °C) during the experimental days in a 2021 and b 2023 seasons. The yellow-shaded areas indicate the period of the experiment conducted in the kiwifruit vineyard. DOY day of the year

Diurnal and seasonal trunk water potential patterns

The diurnal trend of TWP, together with variations in SWC in the 0–30 cm soil layer over a period of three months during the 2021 is shown in Fig. 3 providing a preliminary assessment of the functionality and operability of the MT installed on kiwifruit vines.

The diurnal values of TWP during the irrigation season ranged from about – 0.07 MPa to about – 0.29 MPa (Fig. 3a). A minimum value of about – 0.45 MPa was reached only after irrigation was suspended. That is, after the end of the irrigation season, the TWP gradually decreased from DOY 281 to DOY 308, suggesting that the low rainfall in October was not sufficient to satisfy the water needs of the vines. From DOY 308, TWP values increased due to the beginning of the senescence phase (complete leaf fall) (Fig. 3a).

The SWC in the 0–30 cm soil layer remained close to FC, also by daily splitting of the irrigation volume (DOY 225-DOY 250). As the daily irrigation volumes were distributed in a single intervention (from DOY 250), SWC decreased below 31%vol, reaching a minimum value of about 28%vol (DOY 303) after irrigation was suspended (Fig. 3b).

Seasonal TWP values for the different irrigation treatments imposed in 2023 along with the corresponding SWC considered in the 0–30 and 30–60 cm soil layers are shown in Fig. 4.

Seasonal trends of mean trunk water potential (TWP, n = 2) in kiwifruit vines in a CTRL, b Mild and c Severe irrigation treatments and soil water content (SWC, n = 3) averaged in the 0–30 and 30–60 cm soil layers in d CTRL, e Mild and f Severe irrigation treatments during 2023. TWP of individual sensors are shown in Fig. S5 and SWC data of single probes are shown in Fig. S6

The TWP in the CTRL vines ranged from – 0.007 MPa to – 0.59 MPa throughout the experimental period (Fig. 4a), with minimum values reached early in the afternoon (1–3 PM). An interannual variability of TWP in CTRL vines was observed between the two seasons, with an average maximum difference between minimum values of about 0.16 MPa. In the CTRL treatment, the SWC remained stably above 37.36% in the 0–30 cm soil layer, with decreases associated with variations in irrigation volume and scheduling (Fig. 4d). Low pre-dawn TWP values close to – 0.2 MPa (Fig. 4a) were observed between DOY 247 and DOY 253, when irrigation volumes were reduced from 60 to 45 m3 ha−1 per day. The TWP increased again when daily irrigation volumes were restored to 60 m3 ha−1 at DOY 254 (Fig. 4a).

SWC decreased from 35.28 to 26.48% in the 0–30 cm soil layer in the Mild irrigation treatment between DOY 227 and DOY 237 (Fig. 4e). During these days, the TWP reached pre-dawn values close to – 0.2 MPa and minimum values close to – 0.8 MPa (Fig. 4b). TWP returned to CTRL values when irrigation was increased on DOY 254 (Fig. 4b).

From DOY 220 to DOY 230, irrigation was suspended and reduced in the Severe irrigation treatment, where TWP reached approx. – 0.6 MPa and −1 MPa pre-dawn and midday, respectively (Fig. 4c). Irrigation was restored on DOY 237, allowing the severely stressed vines to enter the recovery phase, which took about three days to restore TWP at CTRL values (Fig. 4c). Irrigation was stopped again, SWC was reduced to 18.49% (Fig. 4f) and a more immediate decrease in TWP was observed, reaching pre-dawn and midday values of approx. – 0.75 MPa and – 1.04 MPa, respectively (Fig. 4c). Irrigation was restored at DOY 256 and TWP returned to control levels within three days (Fig. 4c).

Diurnal (DOY 237) plant water status, indicated by both SWP and TWP, and physiological parameters such as A, gsw and E rates in vines under CTRL, Mild and Severe irrigation treatments are shown in Fig. 5.

Diurnal pattern of a hourly air vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (grey filled area), stem water potential (SWP) measured with the pressure chamber (points), and trunk water potential (TWP) monitored by MT (lines), b stomatal conductance (gsw), c transpiration (E), and d photosynthetic (A) rates in kiwifruit vines in CTRL, Mild and Severe irrigation treatments. Data were measured on DOY 237 during the 2023. Data are mean value ± standard errors (when applicable) (TWP, n = 2; SWP, n = 5; A, E, gsw, n = 4). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) within each time of the day. Note that letters were not reported when there were no significant differences

The lowest values for both SWP and TWP were reached in the early afternoon, slightly shifted from the maximum VPD peak (Fig. 5a). The A was high early in the morning, and remained stable throughout the day and decreased sharply in the late afternoon in the CTRL vines. A similar trend was observed in Mild and Severe vines, whose photosynthetic activity was reduced by 47% and 64% respectively (Fig. 5d). The E was low early in the morning and increased as the environment became more demanding in the middle hours of the day for all irrigation treatments. Reductions of approx. 28% and 41% were achieved in the Mild and Severe treatments, respectively, compared to CTRL (Fig. 5c). The gsw increased with increasing environmental evaporative demand in CTRL vines, while it remained stable and low throughout the day in both water-stressed vines, being reduced by 48% and 56% in the Mild and Severe treatments, respectively (Fig. 5b).

Soil–plant-environment interactions

ΔTWP was significantly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.77, p < 0.001) with VPD under non-limiting soil water conditions (Fig. 6a). Values of TWP shifted backward 4 h were linearly correlated with the VPD in all the irrigation treatments (CTRL r = – 0.98; Mild r = – 1; Severe r = – 0.99), even the irrigation treatment influenced the slope of the scatter (Fig. 6b).

Relationship between a daily maximum oscillation of trunk water potential (ΔTWP) (difference between TWP measured at 3 AM and the minimum TWP) in well irrigated (CTRL) kiwifruit vines and daily maximum values of air vapor pressure deficit (VPD); b paired hourly values of trunk water potential (TWP) and VPD in CTRL, Mild and Severe irrigation treatments recorded from 3 AM to the time corresponding to the minimum TWP in kiwifruit vines. Note that the TWP values were shifted backward four hours to account for the time lag between TWP and VPD

Values of TWP differentially responded to SWC as reported in Fig. 7. Particularly, the TWP at pre-dawn remained above about – 0.2 MPa until SWC decline approached 30% vol. At SWC values below about 30%, the TWP promptly declined and reached the lowest value of about – 0.8 MPa corresponding to about 18% SWC (Fig. 7).

The modelling analysis shows that in well irrigated vines the TWP measured through MT linearly responded to VPD (Adjusted R2 = 0.77) to the extent that the Y ~ VPD model was able to explain 73% of the variance of measured data (Fig. 8, see Table S2 for details on model parameters). In contrast with this, SWC was a weak predictor of TWP (Adjusted R2 = 0.05) and the resulting model was able to explain 13% of the measured data variance (Fig. 8).

Correlation between the measured (test dataset) and predicted TWP employing (left) VPD and (right) SWC as independent variables in well irrigated (CTRL) kiwifruit vines. In each panel the dashed line represents the 1:1 straight line, the continuous line represents the actual measured:predicted fitting model. Each measured value is the mean of two microtensiometer readings recorded hourly during the 2023 season

The Fig. 9 reports the correlation between the predicted and measured TWP covering the whole TWP range recorded across CTRL, Mild, and Severe treatments. The models employing VPD or SWC as predictor had similar R2 of 0.35. In contrast with this, the additive and interaction models increased the goodness of fitting between measured and estimated values (R2 up to 0.66). Model parameters are reported in Table S2. Model accuracy was also appraised using RMSE and MAE to overcome the sensitivity of R2 to outliers (Table 2). These additional metrics were in the same magnitude across the various models, however the Y ~ VPD*SWC model showed the lowest AIC anticipating it was the most accurate (Table 2).

Correlation between the measured (test dataset) and predicted TWP by the various models in kiwifruit vines. Data from all irrigation treatments were pooled before fitting. In each panel the dashed line represents the 1:1 straight line, the continuous line represents the actual measured:predicted fitting model. Each measured value is the mean of two microtensiometer readings recorded hourly during the 2023 season

The constancy of variance of the residuals across the models is reported in Fig. S7 showing that the linearity of variance degrades for the most negative TWP values and particularly for the Y ~ SWC model. In most scenarios, residuals were homogeneously distributed across the range of fitted measurements except for those values at about – 0.1 MPa. The kernel distribution of the models Y ~ VPD + SWC and Y ~ VPD*SWC had a roughly normal distribution, while the remaining models showed a bimodal (Y ~ VPD) or skewed (Y ~ SWC) shape (Fig. S8).

The ANOVA conducted over the data recorded in well irrigated vines (CTRL) and pooling the whole data from CTRL, Mild and Severe irrigation treatments is reported in Table 3. The ANOVA table shows that the additive model fits significantly better than the simple Y ~ VPD one. The ANOVA also shows that the interaction term further significantly improved the model (Table 3).

Relationship between trunk and stem water potential

Daily paired midday SWP and TWP trends in vines under CTRL, Mild and Severe irrigation treatments are shown in Fig. 10. Results indicated that the SWP values were consistent with those of TWP. The lowest values of SWP and TWP were – 1.35 MPa (DOY 236) and −0.73 MPa (DOY 237) for mildly stressed kiwifruit vines, and −2.2 MPa (DOY 255) and – 1.05 MPa (DOY 254) for severely stressed kiwifruit vines.

The relationship between TWP and SWP was examined through a piecewise linear model over the pooled values of all irrigation treatments (Fig. 11). That model showed a breakpoint at about – 1.6 MPa, an adjusted segR2 and segAIC equal to 0.78 and – 246.95, respectively. The TWP and SWP pairwise were also fitted with a linear model (not shown) whose R2 and AIC were 0.76 and −231.04, respectively (Fig. 11).

Correlation between microtensiometer-based trunk water potential (TWP) and pressure chamber-based stem water potential (SWP) recorded in well irrigated (CTRL) kiwifruit vines or progressively subjected to Mild, or Severe drought. Data were pooled before fitting using a segmented linear model. The vertical dashed line indicates the breakpoint at −1.6 MPa. Details on segmented linear model are reported in Table S4. Note that R2 and AIC without “seg.” prefix refer to a linear model fitting the data with no breakpoint

Discussion

Coupling trunk water potential, VPD and soil water content

The VPD is an environmental variable regulating plant water relations and in turn leaf and trunk water potential by affecting leaf transpiration and water transport (Mayr 2021). The present study analyzed the environmental drivers of the microtensiometer-based TWP through models employing VPD and SWC. For that purpose, the dataset was filtered accounting for the hysteresis and for the time-lag response of TWP to VPD (see M&M section). Both hysteresis and time-lag are recognized phenomena characterizing the response of plants to environmental stimuli including VPD (e.g., Amato et al. 2021; Wan et al. 2023). However, while the time-lag was accounted for in existing studies dealing with microtensiometer (e.g., Pagay 2022; Blanco and Kalcsits 2023), the hysteresis did not yet enter the discussion. Hence, this study would also contribute to expanding current knowledge on this specific topic.

The shading factor of net might range from 9% up to 92% (Mahmood et al. 2018). In the present study, the net had 8% shading (hole size 2.2 × 2.6 mm) hence it could be considered minimally shaded. A similar (9%) shading net did not influence air temperature in a banana plantation (Mekhmandarov et al. 2015). Hence, it can be reasonably assumed that the effect of 8% shading on microenvironment was negligible, however it remains to be specifically tested. According to the idea that VPD dominates plant water relations, results show that VPD satisfactorily drives the TWP (model R2 = 0.74) in the range of plants under well water conditions. This result aligns with those in well-watered pear (Blanco and Kalcsits 2023), grapevine (Williams and Baeza 2007; Pagay 2022), olive (Shackel et al. 2021) and apple (Nieto et al. 2023). The SWC in well-irrigated conditions fails to drive TWP because of the stable soil moisture along the day whilst TWP has a diurnal cycle (Fig. 7, 8).

The models employed in the present study were also parametrized and fitted over a relatively large range of TWP (from about −0.01 MPa down to about – 1.1 MPa) achieved after the imposition of the Mild and Severe treatments. Under these variable SWC conditions (from about 40%vol to about 18%vol) the vine water potential changed as expected (Mills et al. 2009; Silva and Ferreira 2014; Calabritto et al. 2024). Hence, it could be anticipated that entering the SWC term in the model would be essential to improve the predicting capability of the model based on VPD. In line with this, results document that the additive and interaction models significantly improved model prediction (see ANOVA in Table 3) and that the interaction one would definitely provide the best fit. However, considering the relatively small reduction in RSS comparing the interaction and additive models, and that the model Y ~ VPD*SWC had the lowest AIC, it could be concluded that the interaction model offers the best fit. Hence, the present paper returns the information that within a diurnal time-scale when the soil moisture is non limiting, the VPD would act as the main driver of TWP and that SWC down-regulates the effect of VPD when SWC becomes limiting (< 30%vol in this study). The effect of SWC on TWP resembles the correlation between soil moisture and some plant physiological traits (e.g., leaf relative water content, stomatal conductance) showing that SWC is influential on these traits once it declines below a threshold (e.g., Abrisqueta et al. 2012; Du et al. 2012). Results on the nested models are difficult to compare because most studies considered only the VPD as explanatory variable of MT under stable and non-limiting soil moisture. For example, in Blanco and Kalcsits (2023) a linear correlation is reported between TWP measured through MT and VPD in well irrigated pear trees.

In the present study, the correlation between SWC and TWP (Fig. 7) suggests a variable role of SWC on TWP depending on the SWC level. That is, at soil moisture close to FC the SWC term would not influence the diurnal TWP which would be almost entirely driven by VPD. In contrast with this, at SWC < 30% the TWP responded also to SWC. Hence, the SWC should enter the model as a non-linear term to putatively further improve the explanation of MT dependencies. Incidentally, this might also improve the homogeneity of variance of residuals at shallow MPa values (Fig. S7). But this remains to be specifically examined.

TWP vs SWP relationship

Nowadays there is an increasing demand for easily accessible and real time proxy of plant traits monitoring the plant response to changing environment (e.g., soil salinity, drought, heat waves) (Briglia et al. 2020; Montanaro et al. 2024a; Velazquez-Chavez et al. 2024). In this context, the use of MT to retrieve plant water status is being compared with SWP, which is believed to provide the actual plant water potential (Naor 2000; Shackel 2007, 2011). For example, previous studies investigating the relationship between TWP and SWP found comparable values between the two methods (Lakso et al. 2022a; Blanco and Kalcsits 2023; Conesa et al. 2023). However, discrepancies between TWP and SWP were reported by Pagay (2022) in grapevines with TWP values generally higher than SWP. Similarly, a mean difference of 0.3 MPa was found between SWP and TWP in nectarine trees (Conesa et al. 2023). The TWP has also been compared against leaf water potential (LWP), showing that TWP is about 1.8 (peach) and 1 MPa (grapevine) higher than LWP (Pagay 2022; Conesa et al. 2023).

The present paper reports the TWP linearly correlated with the SWP but with a differing slope in severely drought stressed vines. The segmented linear regression (Fig. 11) shows the TWP decreases slowly at SWP values below −1.6 MPa suggesting trunk and leaf differ in water economy particularly under limited water condition. The improvements of AIC and R2 achieved by the segmented linear model suggest it would be the best one (see Fig. 11). In addition, there are others (physiological) arguments supporting a piecewise model. For example, plant tissues might differently release water to transpiration flow according to their capacitance (specific volumetric water content released per unit of declining water potential) (Scholz et al. 2007). Leaf and trunk would considerably differ in their capacitance because (i) the trunk has a large water storage compartment, and (ii) because of the water potential gradient existing between canopy and trunk. Transpiration-induced xylem pressure drops are reduced by the release of water stored in tissue into the transpiration stream (Meinzer et al. 2009; Scholz et al. 2011), resulting in a less pronounced drop in water potential (i.e., TWP). Based on the location of the MT measuring point (between roots and canopy) and on the level of buffering of water potential in the trunk, the TWP has been previously reported as the most stable indicator of plant water status (Lakso et al. 2022a; Pagay 2022). In the present study, TWP showed higher values than SWP (Fig. 11) consistently with the establishment of a water potential gradient within the plant (Begg and Turner 1970; Hellkvist et al. 1974; Sharwies and Dinneny 2019; Pagay 2022). Lakso et al. (2022b) observed a faster response from the outside of the canopy than from the trunk, suggesting the involvement of trunk capacitance and the speed of water potential gradient propagation within the plant. The tissue capacitance might help also to explain different behavior of MT across various species (Scholz et al. 2011) whose wood might have different capacitance-related traits (e.g., density, parenchima/sapwood ratio) (Carrasco et al. 2015).

The use of tissue (trunk) water reservoir results from the interplay between different meteorological drivers (including VPD) through their impact on water flow and water potential in trees (Verbeeck et al. 2007). In line with this, it is conceivable that the diurnal hysteresis of the MT has been triggered by the releasing water process from woody reservoirs supporting the transpiration stream (Scholz et al. 2011). Thereafter, the refilling process likely lags behind the transpiration and might buffer the oscillations of xylem tension (Scholz et al. 2011). The hysteresis phenomena is relatively common in various research fields (e.g., electronics, geophysics, human health (e.g., Morris 2012; Ross et al. 2016; Paterson et al. 2018). Within plant science, some physiological responses to stimuli show a hysteresis such as the efficiency of photosynthetic apparatus triggered by light availability (Serôdio et al. 2022), the diurnal transpiration (Amato et al. 2021), and even the seasonal changes in fruit color (Montanaro et al. 2024b). The hysteresis phenomenon has been also reported in field studies in cherry and olive explaining the diurnal growth of fruit in response to VPD (Khosravi et al. 2021; Zucchini et al. 2021).

The change in slope between TWP and SWP might also be related to a differential stomatal regulation of water loss occurring under well irrigation and drought. Under non-limiting water conditions, kiwifruit sustains high rates of gsw, and E (Fig. 5b, c), lowering the hydrostatic pressure gradient (ΔP) which propagates down to the trunk. In contrast with this, under reduced soil water availability gas exchanges are reduced by more than 50% during the central part of the day (Fig. 5b, c, d) (Montanaro et al. 2009), and likely slowing the ΔP propagation and in turn the TWP reduction.

This result might apparently contrast with existing correlation between SWP and TWP in grapevine (Pagay 2022) and pear (Blanco and Kalcsits 2023). However, the range of SWP reached in the present study was likely larger than that in the above-mentioned ones unmasking the segmented correlation. Moreover, it could be noted that values of E and gsw across treatments where not coupled early in the morning (high gsw in Mild vines, while E remained comparable) likely because of variable boundary layer and molar concentration of water vapor within the leaf. This might have contributed to that nonlinearity, but this remains to be specifically tested.

The water potential drop in the plant (i.e., that reached at midday) depends on transpiration rate and hydraulic transport capacity, which are determined by stomatal and hydraulic conductance (Martínez-Vilalta and Garcia-Forner 2017), and then vary according to the plant ability to uptake and transport upward to the canopy the water needed by the transpiration flow. Kiwifruit is recognized to have a high hydraulic conductivity of the stem and efficiency in water transport, associated with anatomical features of xylem vessels, which allow it to sustain high transpiration rate despite the high leaf/stem biomass ratio (Gucci et al. 1997). Dichio et al. (2013) confirmed a relatively high leaf-specific whole-plant conductance in kiwifruit.

Limitations

The results obtained during two years of experimentation confirm MT as a promising tool in kiwifruit and recognize some limitations for the correct and long-term functioning of the sensor in this crop. Throughout the two seasons, sensors were able to track TWP for a relatively short period ranging from a few weeks to a maximum of five months. The installation process and the proper contact between the sensor and the xylem are important for the correct functioning of MT. Once the installation was done correctly, MT rarely showed unrealistic values. In general, it suddenly stopped working, and even reinstalling it did not recovery the signal. For all non-functioning sensors, the first indication of sensor failure and malfunction was evident from the daily TWP trends, which showed the same values for several consecutive readings (Fig. 12a).

The peculiar morphology of the kiwifruit epidermal tissues may contribute to the short life of the sensor, in particular the low bark hardness and tissue elasticity led to the formation of a crack after sensor installation (Fig. 12b), aided by an unequal growth rate of the tissues. The cracks gradually extended along the trunk surface and penetrated the vascular tissue, both phloem and xylem. The phloem, which is thick (5–6 mm) (Fig. 12c), once damaged, probably allowed air to enter the xylem, which may result in the loss of the tension gradient.

Conclusions and potential use of TWP for irrigation management

In conclusion, modelling the TWP and the explanatory environmental drivers shows the TWP differentially responded to VPD and SWC depending on the time scale considered. Within a diurnal scale, TWP is mainly driven by VPD and shows a hysteresis response likely triggered by the release of water from woody reservoirs. Under a progressive depletion of soil moisture, TWP aligns also to SWC, even though further improvements of modelling should consider the SWC as a second order term. However, in the case of a steep change in SWC (e.g. during recovery), the increase in soil moisture allows the TWP to respond within a couple of hours.

TWP linearly correlates with the SWP, which is recognized as the reference indicator for assessing plant water status, but with a differing slope in severely drought stressed vines. The piecewise linear regression model shows the TWP decreases slowly at SWP values below – 1.6 MPa, suggesting a differential release of water from plant tissues to the transpiration stream according to their capacitance. Considering the correlation between TWP and SWP and its prompt response to changes in SWC, it appears that MT is sensitive to plant, soil and environmental factors supporting its potential employment in irrigation management in kiwifruit.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrisqueta I, Vera J, Tapia LM, Abrisqueta JM, Ruiz-Sánchez MC (2012) Soil water content criteria for peach trees water stress detection during the postharvest period. Agric Water Manag 104:62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2011.11.015

Ahumada-Orellana L, Ortega-Farías S, Poblete-Echeverría C, Searles PS (2019) Estimation of stomatal conductance and stem water potential threshold values for water stress in olive trees (cv. Arbequina). Irrig Sci 37:461–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-019-00623-9

Amato D, Montanaro G, Vurro F, Coppedé N, Briglia N, Petrozza A, Janni M, Zappettini A, Cellini F, Nuzzo V (2021) Towards in vivo monitoring of ions accumulation in trees: Response of an in planta organic electrochemical transistor based sensor to water flux density, light and vapor pressure deficit variation. Appl Sci 11(11):4729. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114729

Améglio T, Archer P, Cohen M, Valancogne C, Daudet FA, Dayau S, Cruiziat P (1999) Significance and limits in the use of predawn leaf water potential for tree irrigation. Plant Soil 207:155–167. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026415302759

Bai Y, Li X, Liu S, Wang P (2017) Modelling diurnal and seasonal hysteresis phenomena of canopy conductance in an oasis forest ecosystem. Agric for Meteorol 246:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.06.006

Begg JE, Turner NC (1970) Water potential gradients in field tobacco. Plant Physiol 46(2):343–346. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.46.2.343

Blanco V, Kalcsits L (2021) Microtensiometers accurately measure stem water potential in woody perennials. Plants 10:2780. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10122780

Blanco V, Kalcsits L (2023) Long-term validation of continuous measurements of trunk water potential and trunk diameter indicate different diurnal patterns for pear under water limitations. Agric Water Manag 281:108257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108257

Blanco V, Domingo R, Pérez-Pastor A, Blaya-Ros PJ, Torres-Sánchez R (2018) Soil and plant water indicators for deficit irrigation management of field-grown sweet cherry trees. Agric Water Manag 208:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.05.021

Briglia N, Williams K, Wu D, Li Y, Tao S, Corke F, Montanaro G, Petrozza A, Amato D, Cellini F, Doonan JH, Yang W, Nuzzo V (2020) Image-based assessment of drought response in grapevines. Front Plant Sci 11:595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00595

Calabritto M, Mininni AN, Di Biase R, Pietrafesa A, Dichio B (2024) Spatio-temporal dynamics of root water uptake and identification of soil moisture thresholds for precision irrigation in a Mediterranean yellow-fleshed kiwifruit orchard. Front Plant Sci 15:1472093. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1472093

Carrasco LO, Bucci SJ, Di Francescantonio D, Lezcano OA, Campanello PI, Scholz FG, Rodríguez S, Madanes N, Cristiano PM, Hao GY, Holbrook NM, Goldstein G (2015) Water storage dynamics in the main stem of subtropical tree species differing in wood density, growth rate and life history traits. Tree Physiol 35(4):354–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpu087

Chartzoulakis K, Noitsakis B, Therios I (1993) Photosynthesis, plant growth and dry matter distribution in kiwifruit as influenced by water deficits. Irrig Sci 14:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00194999

Conesa MR, Conejero W, Vera J, Ruiz-Sánchez MC (2023) Assessment of trunk microtensiometer as a novel biosensor to continuously monitor plant water status in nectarine trees. Front Plant Sci 14:1123045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1123045

Dastane NG (1974). Effective rainfall in irrigated agriculture. Irrigation and drainage paper 25, FAO, Flood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

De Swaef T, Steppe K, Lemeur R (2009) Determining reference values for stem water potential and maximum daily trunk shrinkage in young apple trees based on plant responses to water deficit. Agric Water Manag 96:541–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2008.09.013

del Pozo A, Brunel-Saldias N, Engler A, Ortega-Farias S, Acevedo-Opazo C, Lobos GA, Jara-Rojas R, Molina-Montenegro MA (2019) Climate change impacts and adaptation strategies of agriculture in Mediterranean-climate regions (MCRs). Sustain 11:2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102769

Dichio B, Montanaro G, Sofo A, Xiloyannis C (2013) Stem and whole-plant hydraulics in olive (Olea europaea) and kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa). Trees 27:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-012-0787-3

Du YL, Wang ZY, Fan JW, Turner NC, Wang T, Li FM (2012) β-Aminobutyric acid increases abscisic acid accumulation and desiccation tolerance and decreases water use but fails to improve grain yield in two spring wheat cultivars under soil drying. J Exp Bot 63(13):4849–4860. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers164

Fernandes-Silva A, Oliveira M, Paço TA, Ferreira I (2018) Deficit irrigation in Mediterranean fruit trees and grapevines: Water stress indicators and crop responses. In: Ondrašek G (ed) Irrigation in agroecosystems. IntechOpen, London, pp 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.80365

Fernández JE (2017) Plant-based methods for irrigation scheduling of woody crops. Horticulturae 3:35. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae3020035

Fulton A, Buchner R, Olson B, Schwankl L, Gilles C, Bertagna N, Walton J, Shackel K (2001) Rapid equilibration of leaf and stem water potential under field conditions in almonds, walnuts, and prunes. HortTechnology 11(4):609–615

Goudriaan J, van Laar HH (1994) Modelling potential crop growth processes. Kluwer Academic Publ, Dordrecht, Boston, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0750-1

Gucci R, Massai R, Xiloyannis C (1997) Mechanism of drought avoidance in kiwifruit vines. Acta Hortic 444:311–316. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1997.444.48

Hellkvist J, Richards G, Jarvis PG (1974) Vertical gradients of water potential and tissue water relations in Sitka spruce trees measured with the pressure chamber. J Appl Ecol. https://doi.org/10.2307/2402215

Hsiao TC (1990) Measurements of plant water status. In: Steward BA, Nielsen DR (Eds), Irrigation of agricultural crops. Agronomy Monograph 30. ASA CSSA and SSSA, Madison, WI, USA, pp. 243–279

Intrigliolo DS, Castel JR (2004) Continuous measurement of plant and soil water status for irrigation scheduling in plum. Irrig Sci 23:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-004-0097-7

Intrigliolo DS, Castel JR (2006) Performance of various water stress indicators for prediction of fruit size response to deficit irrigation in plum. Agric Water Manag 83:173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2005.12.005

Jones HG (2004) Irrigation scheduling: advantages and pitfalls of plant-based methods. J Exp Bot 55:2427–2436. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh213

Jones HG (2007) Monitoring plant and soil water status: established and novel methods revisited and their relevance to studies of drought tolerance. J Exp Bot 58:119–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erl118

Khosravi A, Zucchini M, Giorgi V, Mancini A, Neri D (2021) Continuous monitoring of olive fruit growth by automatic extensimeter in response to vapor pressure deficit from pit hardening to harvest. Horticulturae 7:349. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7100349

Lakso AN, Intrigliolo DS (2022) Plant-based sensing for irrigation management in the field. Acta Hortic 1335:247–262. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2022.1335.30

Lakso AN, Santiago M, Stroock AD (2022a) Monitoring stem water potential with an embedded micro tensiometer to inform irrigation scheduling in fruit crops. Horticulturae 8:1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121207

Lakso AN, Zhu S, Santiago M, Shackel K, Volkov V, Stroock AD (2022b) A microtensiometer sensor to continuously monitor stem water potentials in woody plants – design and field testing. Acta Hortic 1335:317–324. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2022.1335.39

Lampinen BD, Shackel KA, Southwick SM, Olson WH (2001) Deficit irrigation strategies using midday stem water potential in prune. Irrig Sci 20:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002710000028

López-Bernal Á, García-Tejera O, Testi L, Villalobos FJ (2024) Irrigation scheduling using plant-and soil-based methods. In: Villalobos FJ, Fereres E (eds) Principles of agronomy for sustainable agriculture. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, pp 285–303

Mahmood A, Hu Y, Tanny J, Asante EA (2018) Effects of shading and insect-proof screens on crop microclimate and production: a review of recent advances. Sci Hortic 241:241–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.06.078

Martínez-Vilalta J, Garcia-Forner N (2017) Water potential regulation, stomatal behaviour and hydraulic transport under drought: deconstructing the iso/anisohydric concept. Plant Cell Environ 40:962–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12846

Mayr S (2021) Relevance of time and spatial scales in plant hydraulics. Tree Physiol 41(10):1781–1784. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpab093

McCutchan H, Shackel KA (1992) Stem water potential as a sensitive indicator of water stress in prune trees (Prunus domestica L. cv. French). J Am Soc for Hortic Sci 117:606–611

Meinzer FC, Johnson DM, Lachenbruch B, McCulloh KA, Woodruff DR (2009) Xylem hydraulic safety margins in woody plants: coordination of stomatal control of xylem tension with hydraulic capacitance. Funct Ecol 23(5):922–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01577.x

Mekhmandarov Y, Pirkner M, Achiman O, Tanny J (2015) Application of the surface renewal technique in two types of screenhouses: sensible heat flux estimates and turbulence characteristics. Agric for Meteorol 203:229–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.01.010

Mills TM, Li J, Behboudian MH (2009) Physiological responses of gold kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) to reduced irrigation. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 134(6):677–683. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.134.6.677

Mininni AN, Laterza D, Tuzio AC, Di Biase R, Dichio B (2022) Soil water content monitoring as a tool for sustainable irrigation strategy in a kiwifruit orchard under semi-arid conditions. Acta Hortic 1332:203–210. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2022.1332.27

Montanaro G, Dichio B, Xiloyannis C (2007) Response of photosynthetic machinery of field-grown kiwifruit under Mediterranean conditions during drought and rewatering. Photosynthetica 45:533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-007-0091-4

Montanaro G, Dichio B, Xiloyannis C (2009) Shade mitigates photoinhibition and enhances water use efficiency in kiwifruit under drought. Photosynthetica 47:363–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-009-0057-9

Montanaro G, Briglia N, Petrozza A, Carlomagno A, Rustioni L, Cellini F, Nuzzo V (2024a) Image-based sensing of salt stress in grapevine. OENO ONE. https://doi.org/10.20870/oeno-one.2024.58.1.7757

Montanaro G, Carlomagno A, Petrozza A, Cellini F, Manolikaki I, Koubouris G, Nuzzo V (2024b) Predicting oil accumulation by fruit image processing and linear models in traditional and super high-density olive cultivars. Front Plant Sci 15:1456800. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1456800

Moriondo M, Bindi M (2007) Impact of climate change on the phenology of typical Mediterranean crops. Ital J Agrometeorol 3:5–12

Morris KA (2012) What is hysteresis? Appl Mech Rev 64:050801. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4007112

Naor A (2000) Midday stem water potential as a plant water stress indicator for irrigation scheduling in fruit trees. Acta Hortic 537:447–454. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2000.537.52

Naor A (2006) Irrigation scheduling and evaluation of tree water status in deciduous orchards. In: Janick J (ed) Horticultural reviews, vol 32. John Wiley & Sons, Inc New Jersey, pp 111–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470767986.ch3

Nieto LG, Huber A, Gao R, Biasuz EC, Cheng L, Stroock AD, Lakso AN, Robinson TL (2023) Trunk water potential measured with microtensiometers for managing water stress in “Gala” apple trees. Plants 12:1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12091912

Noun G, Lo Cascio M, Spano D, Marras S, Sirca C (2022) Plant-based methodologies and approaches for estimating plant water status of mediterranean tree species: a semi-systematic review. Agronomy 12:2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092127

Pagay V (2022) Evaluating a novel microtensiometer for continuous trunk water potential measurements in field-grown irrigated grapevines. Irrig Sci 40:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-021-00758-8

Pagay V, Santiago M, Sessoms DA, Huber EJ, Vincent O, Pharkya A, Corso TN, Lakso AN, Stroock AD (2014) A microtensiometer capable of measuring water potentials below -10 MPa. Lab Chip 14:2806–2817. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4LC00342J

Pagay V (2021) Dynamic aspects of plant water potential revealed by a microtensiometer. BioRxiv, 2021–06. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.23.449675

Paterson GA, Zhao X, Jackson M, Heslop D (2018) Measuring, processing, and analyzing hysteresis data. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 19(7):1925–1945. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GC007620

Phillips N, Oren R, Zimmermann R, Wright SJ (1999) Temporal patterns of water flux in trees and lianas in a Panamanian moist forest. Trees 14:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004680050216

Pratima P, Sharma N, Kaushal R (2016) Effect of deficit irrigation and in situ moisture conservation on soil moisture content and frequency of irrigation in kiwifruit cultivar Allison. J Appl Nat Sci 8:2093–2098. https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v8i4.1096

Priulla A, D’Angelo N (2024) Sequential hypothesis testing for selecting the number of changepoints in segmented regression models. Environ Ecol Stat 31(2):583–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10651-024-00605-x

Puértolas J, Albacete A, Dodd IC (2020) Irrigation frequency transiently alters whole plant gas exchange, water and hormone status, but irrigation volume determines cumulative growth in two herbaceous crops. Environ Exp Bot 176:104101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104101

R Core Team (2021) R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vol. 2021 (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available at: https://www.R-project.org/

Ross SE, Sperry ZJ, Mahar CM, Bruns TM (2016) Hysteretic behavior of bladder afferent neurons in response to changes in bladder pressure. BMC Neurosci 17(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-016-0292-5

Sakamoto Y, Ishiguro M, Kitagawa G (1986) Akaike information criterion statistics. Springer, Dordrecht Publishing Company

Santesteban LG, Miranda C, Marín D, Sesma B, Intrigliolo DS, Mirás-Avalos JM, Escalona JM, Montoro A, de Herralde F, Baeza P, Romero P, Yuste J, Uriarte D, Martínez-Gascueña J, Cancela JJ, Pinillos V, Loidi M, Urrestarazu J, Royo JB (2019) Discrimination ability of leaf and stem water potential at different times of the day through a meta-analysis in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Agric Water Manag 221:202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.04.020

Scharwies JD, Dinneny JR (2019) Water transport, perception, and response in plants. J Plant Res 132(3):311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-019-01089-8

Scholz FG, Bucci SJ, Goldstein G, Meinzer FC, Franco AC, Miralles-Wilhelm F (2007) Biophysical properties and functional significance of stem water storage tissues in neotropical savanna trees. Plant Cell Environ 30(2):236–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01623.x

Scholz FG, Phillips NG, Bucci SJ, Meinzer FC, Goldstein G (2011) Hydraulic capacitance: biophysics and functional significance of internal water sources in relation to tree size. Size-and age-related changes in tree structure and function, 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1242-3_13

Segovia-Cardozo DA, Franco L, Provenzano G (2022) Detecting crop water requirement indicators in irrigated agroecosystems from soil water content profiles: an application for a citrus orchard. Sci Total Environ 806:150492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150492

Serôdio J, Moreira D, Bastos A, Cardoso V, Frommlet J, Frankenbach S (2022) Hysteresis light curves: a protocol for characterizing the time dependence of the light response of photosynthesis. Photosynthesis Res 154(1):57–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-022-00954-3

Shackel KA (2007) Water relations of woody perennial plant species. J Int des Sci De La Vigne Et Du Vin 41(3):121–129. https://doi.org/10.20870/oeno-one.2007.41.3.847

Shackel K (2011) A plant-based approach to deficit irrigation in trees and vines. Hort Sci 46(2):173–177. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.46.2.173

Shackel KA, Ahmadi H, Biasi W, Buchner R, Goldhamer D, Gurusinghe S, Hasey J, Kester D, Krueger B, Lampinen B, McGourty G, Micke W, Mitcham E, Olson B, Pelletrau K, Philips H, Ramos D, Schwankl L, Sibbett S, Snyder R, Southwick S, Stevenson M, Thorpe M, Weinbaum S, Yeager J (1997) Plant water status as an index of irrigation need in deciduous fruit trees. Hort Technology 7:23–29

Shackel K, Moriana A, Marino G, Corell M, Pérez-López D, Martin-Palomo MJ, Caruso T, Marra FP, Alcaras LMA, Milliron L, Rosecrance R, Fulton A, Searles P (2021) Establishing a reference baseline for midday stem water potential in olive and its use for plant-based irrigation management. Front Plant Sci 12:791711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.791711

Silva RM, Ferreira MI (2014) A new microdendrometric index to quantify water status in kiwifruit. Acta Hortic 1038:43–50. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2014.1038.3

Stewart WL, Fulton AE, Krueger WH, Lampinen BD, Shackel KA (2011) Regulated deficit irrigation reduces water use of almonds without affecting yield. Cal Ag 65:90–99

Velazquez-Chavez LJ, Daccache A, Mohamed AZ, Centritto M (2024) Plant-based and remote sensing for water status monitoring of orchard crops: systematic review and meta-analysis. Agric Water Manag 303:109051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2024.109051

Vera J, Conejero W, Conesa MR, Ruiz-Sánchez MC (2019) Irrigation factor approach based on soil water content: a nectarine orchard case study. Water 11:589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030589

Verbeeck H, Steppe K, Nadezhdina N, Op De Beeck M, Deckmyn G, Meiresonne L, Lemeur R, Čermák J, Ceulemans R, Janssens IA (2007) Model analysis of the effects of atmospheric drivers on storage water use in Scots pine. Biogeosciences 4:657–671. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-657-2007

Wan L, Zhang Q, Cheng L, Liu Y, Qin S, Xu J, Wang Y (2023) What determines the time lags of sap flux with solar radiation and vapor pressure deficit? Agric for Meteorol 333:109414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109414

Wang Z, Sun Z, Cui J (2023) Time lag effect on solar radiation of tree sap flux density for different DBH of Larix olgensis. J Plant Ecol 16(3):rtac092. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtac092

Williams LE, Baeza P (2007) Relationships among ambient temperature and vapor pressure deficit and leaf and stem water potentials of fully irrigated, field-grown grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic 58(2):173–181. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.2007.58.2.173

Xiloyannis C, Montanaro G, Dichio B (2012). Kiwifruit. In Steduto P, Hsiao T C, Fereres E, Raes D (Eds) Crop yield response to water. Irrigation and drainage paper Nr. 66, FAO, Rome, Italy, pp 488–497

Xiloyannis C, Dichio B, Mininni AN (2023) Vine nutrition and water requirement. In: Richardson AC, Burdon JN, Ferguson AR (eds) Kiwifruit: botany, production and uses. CAB International, Boston, pp 164–183

Zeppel MJ, Murray BR, Barton C, Eamus D (2004) Seasonal responses of xylem sap velocity to VPD and solar radiation during drought in a stand of native trees in temperate Australia. Funct Plant Biol 31(5):461–470. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP03220

Zucchini M, Khosravi A, Giorgi V, Mancini A, Neri D (2021) Is there daily growth hysteresis versus vapor pressure deficit in cherry fruit? Horticulturae 7:131. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7060131

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. A. C. Tuzio for support in the water budget calculation and in irrigation management, to Dr. D. Laterza for technical and logistic support in the experimental trial and to the field owner Giacomo Xiloyannis for hosting the trial.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Basilicata within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This study has been partially supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) in the frame of the PON "RICERCA E INNOVAZIONE" 2014–2020 Project RESO "Sistemi di coltivazione resilienti, valutazione di impatto delle produzioni frutticole", AGRIFOOD CUP B34I200000320005 and in the frame of the Ecosistema TECH4YOU – Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement—Missione 4 Componente 2 Investimento 1.5 NextGenerationEU ECS00000009 CUPC43 C22000400006—PP 3.3.1 SMART WATER.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: B.D.; Methodology: R.D.B, M.C.; Formal analysis and investigation: R.D.B, M.C., G.M., A.N.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: R.D.B, M.C.; Writing—review and editing: All authors; Funding acquisition: B.D.; Resources: B.D., G.M., A.N.M.; Supervision: B.D., G.M., A.N.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Biase, R., Calabritto, M., Mininni, A.N. et al. Microtensiometer-based trunk water potential as a plant water status indicator in kiwifruit under different soil water availability. Irrig Sci 43, 937–954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-025-01020-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-025-01020-1