Abstract

Background

There is a lack of data regarding the knowledge and perceptions teaching faculty possess about breast pumping among general surgery residents despite breast pumping becoming more common during training. This study aimed to examine faculty knowledge and perceptions of breast pumping amongst general surgery residents.

Methods

A 29-question survey measuring knowledge and perceptions about breast pumping was administered online to United States teaching faculty from March–April 2022. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize responses, Fisher’s exact test was used to report differences in responses by surgeon sex and age, and qualitative analysis identified recurrent themes.

Results

156 responses were analyzed; 58.6% were male and 41.4% were female, and the majority (63.5%) were less than 50 years old. Nearly all (97.7%) women with children breast pumped, while 75.3% of men with children had partners who pumped. Men more often than women indicated “I don’t know” when asked about frequency (24.7 vs. 7.9%, p = 0.041) and duration (25.0 vs. 9.5%, p = 0.007) of pumping. Nearly all surgeons are comfortable (97.4%) discussing lactation needs and support (98.1%) breast pumping, yet only two-thirds feel their institutions are supportive. Almost half (41.0%) of surgeons agreed that breast pumping does not impact operating room workflow. Recurring themes included normalizing breast pumping, creating change to better support residents, and communicating needs between all parties.

Conclusions

Teaching faculty may have supportive perceptions about breast pumping, but knowledge gaps may hinder greater levels of support. Opportunities exist for increased faculty education, communication, and policies to better support breast pumping residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast milk is the best source of nutrition for newborns and infants [1]. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends its exclusive use through the first six months of life. Recently, updated guidelines recommended breastfeeding for two years and beyond as desired by mother and child [2]. Despite guidance, breastfeeding rates drop from 83.9 to only 56.7% six months after birth [3]. Though the circumstances and decision to stop breastfeeding is unique to everyone, returning to work undoubtedly contributes. Breastfeeding consumes ~ 25% of the body’s daily energy and requires ~ 500 h over six months [4, 5]. Returning to work while balancing these added demands requires the availability of appropriate facilities and allocated time to meet breastfeeding/pumping needs [6, 7]. Further, organizational and co-worker support are essential for continuing breastfeeding once returning to work [8,9,10,11,12].

Women physicians face additional challenges once returning to work, including limited maternity leave, long work hours, lack of lactation facilities, lack of policies/support, limited flexibility in schedules, and increased work-related stressors that may negatively impact milk production [7, 13,14,15,16,17,18]. Unfortunately, women physicians also experience stigma and discrimination when breastfeeding/pumping [15, 16, 19, 20]. These obstacles are encountered throughout training and in all fields: surgical residency is not immune [21, 22]. As the number of female trainees in surgery increases, childbearing during training and practice has become omnipresent, including the practice of breast pumping at work [23,24,25,26]. However, in a 2018 study, despite 95.6% of general surgery residents indicating breastfeeding was important to them, 58.1% stopped early due to challenges in the workplace [27].

Gender discrimination among female general surgery residents in the United States is common with ~ 80% of female surgery trainees experiencing it [28]. To help alleviate this pervasive issue, it is critical to identify areas in training where this may be occurring. One area may be the support provided to residents who breastfeed/pump. To our knowledge there is a paucity of data on the knowledge and perceptions that teaching faculty have about breast pumping in surgical trainees. In this study we sought to (1) evaluate the knowledge and perceptions of general surgery teaching faculty toward breast pumping residents and (2) identify areas of improvement. We hypothesized that a general lack of knowledge about breast pumping may ultimately contribute to misperceptions about its practice.

Material and methods

Survey development

A 29-question survey was developed to evaluate knowledge and perceptions of breast pumping. Questions were generated from interviews of general surgery residents and faculty, noting key themes. The survey was reviewed by residents, faculty, and survey-development experts. After piloting it at two academic general surgery programs, a final version (Supplemental Material) was created using QuestionPro Survey Software (Survey Analytics LLC, Austin, TX, USA) and approved exempt by the Virginia Commonwealth University institutional review board (IRB#: HM20023438).

Survey content

After consenting, teaching faculty were permitted to complete the survey. Self-reporting of sex, age, specialty, and practice was included. Surgeons were asked if they had biological children. If “yes,” they were then asked if they personally breast pumped or their partner breast pumped.

Questions then examined knowledge of breast pumping such as duration, frequency, and location of lactation facilities. A 5-point Likert scale of Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree assessed surgeon perceptions to how breast pumping impacts the daily workflow, and their personal and institutional support for breast pumping. Finally, an open-ended question provided opportunity for any remaining comments.

Survey distribution

To target teaching faculty, the Association of Program Directors in Surgery email listserv was selected and after approval, the survey was distributed three times with a request to forward the survey to teaching faculty [29]. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, singular, and without compensation. Data were collected over four weeks from March–April 2022.

Statistical analysis

According to the American Association of Medical Colleges there are approximately 6,300 academic general surgery and subspecialty-related surgeons in the United States [30]. Using a power of 80% with a margin of error of 5%, a sample size of 160 responses was calculated. To address missingness, responses that contained 20% or more missing items were excluded from analysis.

Responses to Likert-scale questions were converted to “Agreed,” “Neutral,” and “Disagreed.” During the survey development process, two specific demographic subgroups were identified as having potentially differing perceptions: surgeon sex and age. Descriptive statistics and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze differences in subgroup responses (male vs. female and < 50 years old vs. ≥ 50 years old). All statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.1.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with an alpha value of 0.05.

Thematic analysis

Recurring themes were identified from open-ended responses. Two authors (D.C.F. and V.V.) independently reviewed all responses and generated codes. Codes were used to identify recurring themes on multiple iterations of review. Codebooks were reconciled between authors until full agreement and generated using Dedoose Version 9.0.46 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Of note, throughout this manuscript we use the terms “female” or “women,” but understand that some lactating individuals may identify with a different gender identity.

Results

In total, 187 of 191 (97.9%) surgeons consented to participate. Of these, 178 (95.2%) respondents identified as teaching faculty and could complete the remainder of the survey. A total of 156 (87.6%) responses had ≥ 80% complete data and were analyzed (Fig. 1). It is unknown how many faculty were reached with this survey, so a formal response rate cannot be determined.

Participant demographics

Responses were collected from 89 male surgeons (58.6%) and 63 female surgeons (41.4%) (Table 1). Most surgeons were < 50 years of age (63.5%, 99/156) and have practiced for < 10 years (53.2%, 83/156). The top five specialties were acute care/trauma/critical care (32.9%, 51/155), general surgery (23.9%, 37/155), surgical oncology (7.1%, 11/155), colorectal (7.1%, 11/155), and pediatric surgery (5.8%, 9/155). Responses were collected throughout the United States with most surgeons practicing in urban (75.6%, 118/156) and academic (73.7%, 115/156) settings. Over forty percent (42.3%, 66/156) of surgeons are involved in their residency’s leadership.

Three quarters (76.3%, 119/156) of respondents have children. Of the 44 female surgeons with children, 43 (97.7%) stated that they breast pumped, while 75.3% (55/73) of male surgeons with children indicated that their partner breast pumped.

Breast pumping knowledge

Three questions evaluated teaching faculty knowledge of breast pumping (Table 2). When asked how long it may take a resident to breast pump, 23.7% (37/156) responded 16–30 min, 39.7% (62/156) responded 31–45 min, and 18.6% (29/156) responded “I don’t know.” Responses varied significantly by surgeon sex with male surgeons more often indicating “I don’t know” than female surgeons (24.7 [22/89] vs. 7.9% [5/63], p = 0.041). When asked how often someone may need to breast pump during the day, almost two–thirds (64.5%, 100/155]) of surgeons chose “every 3–4 h” and 19.4% (30/155) indicated they do not know. Responses varied significantly by surgeon sex and age with male surgeons and those ≥ 50 years old choosing “I don’t know” more often than female surgeons (25.0 [22/88] vs. 9.5% [6/63], p = 0.007) and those < 50 years old (31.6 [18/57] vs. 12.2% [12/98], p = 0.001), respectively. The location of lactation facilities was not uniform. Only 12.3% (19/155) of respondents stated there are lactation facilities adjacent to the operating rooms. A substantial proportion (29.7%, 46/155) did not know where facilities exist with men more likely than women indicating this (39.8 [35/88] vs. 15.9% [10/63], p = 0.016).

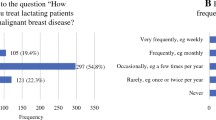

Breast pumping perceptions

Responses to breast pumping perception questions are summarized in Fig. 2. Nearly all respondents (97.4%, 152/156) agreed they are comfortable discussing lactation/breast pumping needs with a resident and 98.1% (153/156) support a resident’s need to breast pump. Despite this support, only two–thirds (66.0%, 103/156) feel that their institutions have a supportive culture for breast pumping. Female compared to male (44.4 [28/63] vs 20.2% [18/89], p = 0.006) and younger compared to older (41.4 [41/99] vs. 10.5% [6/57], p < 0.001) surgeons disagreed that there is adequate time to pump during the workday. With respect to workflow, only 41.0% (64/156) and 47.7% (74/155) of surgeons do not believe a resident excusing themselves to breast pump negatively affects workflow in the operating room or floors, respectively. Furthermore, 14.1% (22/156) of surgeons expected a resident to find a replacement during a case if they scrub out to breast pump. Additionally, 6.4% (10/156) of all respondents believe that residents should continue working while pumping (e.g., charting on the computer); these beliefs did not vary by surgeon sex or age.

Thematic results

Of the 156 responses, 47 (30.1%) surgeons responded to the open–ended question with most responses from women (62.2%, n = 28). Four themes were identified and are presented with representative quotes (Table 3).

Theme 1: Breast pumping is a natural activity that should be normalized

Surgeons overwhelmingly responded that breast pumping is a normal, healthy activity, and recognized its benefit for both mother and baby. Respondents suggested that increasing education about it, such as its duration and frequency, would be valuable for faculty, helping normalize it.

Theme 2: Changes are needed to better support breast pumping general surgery residents

Surgeons suggested that changes should be initiated from leadership within residency programs, surgical departments, and institutions, as these individuals have the power to advocate for residents. Additionally, clearly written–out guidelines and policies are needed.

Theme 3: A resident leaving an OR to breast pump can be disruptive, but these disruptions are manageable and acceptable

A resident leaving a case to breast pump is inevitably inconvenient, but faculty are still supportive of the practice and encourage it. They recognized that if a resident tries to avoid leaving a case, they can be at risk for mastitis and decreased milk supply. Also, it was expressed that many residents already manage this well by pumping before or after cases, causing minimal inconveniences.

Theme 4: Communicating lactational needs is key to establishing expectations

Respondents stated that misunderstandings could be easily remedied by residents communicating their lactational needs with attendings prior to the start of rotations or cases. This would set expectations, from how long one will be out of the case or if a replacement resident is needed.

Discussion

Here we report the first study to evaluate the knowledge and perceptions of general surgery teaching faculty on breast pumping in surgical training. Overall, surveyed faculty are largely supportive of breast pumping. However, there appears to be a general lack of knowledge surrounding the practice, which may be hampering greater levels of support amongst faculty. Furthermore, there are different knowledge levels of breast pumping by surgeon age and sex, which is not surprising as commercial at-home breast pumping gained popularity starting in the 1990s [31].

These knowledge gaps warrant increased education for teaching faculty. First and foremost, all faculty should be informed that federal and state laws protect the rights of mothers to have breaks throughout the day to express milk in private locations [32]. This may not be well-known and as a result, comments such as suggesting a resident delay pumping while scrubbed, are ill-informed. Additional education should include information on the average frequency and time required to breast pump, as well as the benefits of pumping [33]. Such education may demystify its practice and increase understanding. While education is important, communication between residents and faculty may be the most valuable intervention [34]. Open communication between all establishes expectations from both sides. Moreover, according to our data, teaching faculty are comfortable discussing such needs and encourage open communication.

Female mentorship is particularly important to female trainees in medicine and surgery [35,36,37,38]. As with pregnancy, breast pumping is an opportunity for female faculty with personal experience to provide guidance and support for these residents [39]. Regular check-ins with breast pumping (and all postpartum) residents should be strongly encouraged to assess how they are coping with these major life adjustments. This can include sharing how to balance breast pumping with clinical duties, discussing a residents’ emotional well-being, and ensuring residents are aware of policies and available resources. Female faculty and leadership can be the much-needed advocates for breast pumping residents by ensuring their ability to breast pump and recognizing that there is no one-size-fits-all experience for pumping.

Furthermore, respondents expressed the need for policies that clearly establish support for breast pumping. These responses reflect recent efforts across specialties to increase inclusivity by providing private and accessible lactation facilities and cultivating cultural change [40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Lactation facilities should be private and easily accessible to the operating room for surgical residents (and attendings). They should include a sink and refrigerator for cleaning parts and storage of breast milk. Although residents should not be expected to continue working while pumping, providing computers with access to the electronic medical record may minimize potential workflow disruptions if a resident wishes and is able to use it simultaneously while pumping.

Additionally, to further support residents breastfeeding and breast pumping, it is important to promote policy change for maternity leave, as the duration of breastfeeding has been shown to be positively associated with the duration of maternity leave [6, 47]. Despite recent changes by the American Board of Surgery, some advocate further changes and flexibility to the current leave policy to better support residents with children [48,49,50]. Increasing the duration of maternity leave may further support and encourage breastfeeding amongst surgical residents.

Though our study elucidates a unique perspective on breast pumping, we do acknowledge its limitations that restrict the generalizability of our results beyond those surveyed. Biases, including response, sampling, recall, and social desirability, cannot be overlooked. For example, individuals more passionate about the topic may have been more likely to respond, potentially skewing the results to a more favorable view of breast pumping. Our small sample size also likely does not represent the current general surgeon workforce or general surgery residency program demographics, thus, under/over-representing certain groups such as female surgeons and academic programs [51, 52]. Despite these limitations, we do believe our results are the first of their kind and notably contribute to conversations and efforts to improve the surgical training environment for residents, and warrant dissemination within the surgical community.

As we know from existing literature, as well as anecdotal and personal experience, residents experience conflicting feelings about stepping away from their clinical duties to provide breastmilk for their child [20]. Our results demonstrate that at least of those surveyed, faculty are supportive of breast pumping, and thus, residents should feel empowered to engage in a healthy activity performed by millions of women worldwide. Although our results appear favorable towards breast pumping, we are cautious to interpret these sentiments as universal amongst all surgical faculty and programs. We, therefore, take this opportunity to challenge all those in the surgical community to critically assess the culture and environment surrounding breast pumping at your institutions and programs. As we have outlined above, there are ample opportunities for areas of improvement, and with such evaluation, individual programs can better understand where they fall on the spectrum of support and how they can better support their breast pumping residents. By improving support for breast pumping residents, we may take the necessary strides towards a more inclusive culture for women in surgery.

References

Meek JY, Noble L (2022) Technical report: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 150:e2022057989. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057989

Meek JY, Noble L (2022) Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 150:e2022057988. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057988

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) Results: breastfeeding rates. In: Breastfeeding among US children born 2010 to 2018, CDC National Immunization Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/results.html. Accessed 25 Jul 2022

Butte NF, King JC (2005) Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Public Health Nutr 8:1010–1027. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2005793

Smith JP, Ellwood M (2011) Feeding patterns and emotional care in breastfed infants. Soc Indic Res 101:227–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9657-9

Dutheil F, Méchin G, Vorilhon P et al (2021) Breastfeeding after returning to work: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:8631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168631

Sattari M, Serwint JR, Neal D et al (2013) Work-place predictors of duration of breastfeeding among female physicians. J Pediatr 163:1612–1617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.026

Scott VC, Taylor YJ, Basquin C, Venkitsubramanian K (2019) Impact of key workplace breastfeeding support characteristics on job satisfaction, breastfeeding duration, and exclusive breastfeeding among health care employees. Breastfeed Med 14:416–423. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0202

Zhuang J, Bresnahan MJ, Yan X et al (2019) keep doing the good work: impact of coworker and community support on continuation of breastfeeding. Health Commun 34:1270–1278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1476802

Ross E, Woszidlo A (2022) Breastfeeding in the workplace: attitudes toward multiple roles, perceptions of support, and workplace outcomes. Breastfeed Med 17:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2021.0119

Jantzer AM, Anderson J, Kuehl RA (2018) breastfeeding support in the workplace: the relationships among breastfeeding support, work-life balance, and job satisfaction. J Hum Lact 34:379–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334417707956

Dinour LM, Szaro JM (2017) Employer-based programs to support breastfeeding among working mothers: a systematic review. Breastfeed Med 12:131–141. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0182

Hendrickson M, Davey CS, Harvey BA, Schneider K (2022) breastfeeding among pediatric emergency physicians rates, barriers, and support. Pediatr Emerg Care 38:e1372–e1377

French PT, Dickmeyer JJ, Winterer CM et al (2022) Breastfeeding advocacy: a look into the gap between breastfeeding support guidelines and personal breastfeeding experiences of faculty physicians. Breastfeed Med 17:239–246. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2021.0231

Jain S, Neaves S, Royston A et al (2022) Breastmilk pumping experiences of physician mothers: quantitative and qualitative findings from a nationwide survey study. J Gen Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07388-y

Juengst SB, Royston A, Huang I, Wright B (2019) Family leave and return-to-work experiences of physician mothers. JAMA Netw Open 2:e1913054. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13054

Titler SS, Dexter F (2021) Low prevalence of designated lactation spaces at hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers in Iowa: an educational tool for graduates’ job selection. A Pract 15:e01544. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000001544

Kraus MB, Thomson HM, Dexter F et al (2021) Pregnancy and motherhood for trainees in anesthesiology: a survey of the american society of anesthesiologists. J Educ Perioper Med,https://doi.org/10.46374/volxxiii_issue1_kraus

Garcia-Marcinkiewicz AG, Titler SS (2022) Lactation in anesthesiology. Anesthesiol Clin 40:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2022.01.014

Ames EG, Burrows HL (2019) Differing experiences with breastfeeding in residency between mothers and coresidents. Breastfeed Med 14:575–579. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2019.0001

Merchant SJ, Hameed SM, Melck AL (2013) Pregnancy among residents enrolled in general surgery: a nationwide survey of attitudes and experiences. Am J Surg 206:605–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.04.005

Peters GW, Kuczmarska-Haas A, Holliday EB, Puckett L (2020) Lactation challenges of resident physicians- results of a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20:762. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03436-3

Association of American Medical Colleges (2008) 2008 Physician Specialty data: center for workforce studies. Washington, DC

Association of American Medical Colleges (2020) ACGME Residents and fellows by sex and specialty, 2019. In: Physician Specialty Report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/acgme-residents-and-fellows-sex-and-specialty-2019. Accessed 25 Jul 2022

Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J et al (2012) Pregnancy among women surgeons: Trends over time. Arch Surg 147:474–479. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693

Smith C, Galante JM, Pierce JL, Scherer LA (2013) The surgical residency baby boom: changing patterns of childbearing during residency over a 30-year span. J Grad Med Educ 5:625–629. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-12-00334.1

Rangel EL, Smink DS, Castillo-Angeles M et al (2018) Pregnancy and motherhood during surgical training. JAMA Surg 153:644–652. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0153

Schlick CJR, Ellis RJ, Etkin CD et al (2021) Experiences of gender discrimination and sexual harassment among residents in general surgery programs across the US. JAMA Surg 156:942–952. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3195

Association of Program Directors in Surgery (2022) Procedure for use of the APDS listserv for surveys. In: https://apds.org/about/procedure-for-use-of-the-apds-listserv-for-surveys/

Association of American Medical Colleges (2022) aamc faculty salary report, FY 2021. AAMC, Washington, DC

Garber M (2013) A brief history of breast pumps. In: The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/10/a-brief-history-of-breast-pumps/280728/. Accessed 26 Jul 2022

United States Department of Labor (2010) Section 7(r) of the fair labor standards act-break time for nursing mothers provision topics worker rights for employers resources interpretive guidance state laws news Wage and Hour Division. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/nursing-mothers/lawwww.dol.gov

Mitoulas LR, Davanzo R (2022) Breast pumps and mastitis in breastfeeding women: clarifying the relationship. Front Pediatr 10:856353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.856353

Anderson J, Kuehl RA, Drury SAM et al (2015) Policies aren’t enough: The importance of interpersonal communication about workplace breastfeeding support. J Hum Lact 31:260–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415570059

Shen MR, Tzioumis E, Andersen E et al (2022) Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med 97:444–458. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004563

Mahendran GN, Walker ER, Bennett M, Chen AY (2022) Qualitative study of mentorship for women and minorities in surgery. J Am Coll Surg 234:253–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000000059

Oppenheimer-Velez M, Sims C, Labiner H et al (2022) Women empowering women: assessing the american college of surgeons women in surgery committee mentorship program. J Am Coll Surg 235:375–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000000272

Ferrari L, Mari V, de Santi G et al (2022) Early barriers to career progression of women in surgery and solutions to improve them: a systematic scoping review. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005510

Moore AL, Smink DS, Rangel EL (2022) A pregnant pause—time to address mentorship for expectant residents. JAMA Surg. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.1835

Livingston-Rosanoff D, Shubeck SP, Kanters AE et al (2019) Got milk? Design and implementation of a lactation support program for surgeons. Ann Surg 270:31–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003269

Johnson HM, Mitchell KB, Snyder RA (2019) Call to action: universal policy to support residents and fellows who are breastfeeding. J Grad Med Educ 11:382–384. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00140.1

Wong K, Md R, Beckwith N et al (2021) Medical school hotline advocating for a culture of support for lactating medical residents in hawai’i. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf 80:304–306

Trigo S, Gonzalez K, Valiquette N, Verma S (2021) Creating a lactation-friendly learning environment for medical students and residents: a northern canadian perspective. Breastfeed Med 16:511–515. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0331

Pesch MH, Tomlinson S, Singer K, Burrows HL (2019) Pediatricians advocating breastfeeding: let’s start with supporting our fellow pediatricians first. J Pediatr 206:6–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.057

Creo AL, Anderson HN, Homme JH (2018) Productive pumping: a pilot study to help postpartum residents increase clinical time. J Grad Med Educ 10:223–225. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-17-00501.1

Johnson HM, Torres MB, Tatebe LC, Altieri MS (2022) Every ounce counts: a call for comprehensive support for breastfeeding surgeons by the association of women surgeons. Am J Surg 223:1226–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.12.037

Navarro-Rosenblatt D, Garmendia ML (2018) Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 13:589–597. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0132

American Board of Surgery (2021) Leave policy—general surgery. In: https://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?policygsleave

Marincola Smith P, Nordness MF, Polcz ME (2022) The american board of surgery should reconsider its parental leave policy. JAMA Surg 157:7–8

George EL, Fox P, Hawn MT (2021) Life happens, even to surgical trainees. JAMA Surg. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.1811

Association of American Medical Colleges (2021) Physician specialty data report: active physicians by sex and specialty, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

American Medical Association (2023) FREIDA AMA: Surgery-general. In: FREIDA. https://freida.ama-assn.org/specialty/surgery-general. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

Acknowledgements

This study was not directly funded; however, the authors are supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (T32 HG008958 to ANR, KMH) and National Cancer Institute (R01 CA242003 to JGT, U54 CA233444 to JGT, U54 CA233444-03S1 to ANR and JGT, and T32 CA093423-13 to DCF) of the National Institutes of Health and the Joseph and Ann Matella Fund for Pancreatic Cancer Research (JGT).

Funding

This study was not directly funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to (1) conception and design, and/or acquisition of data, and/or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) all authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted and any revised version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved exempt by the Virginia Commonwealth University institutional review board (IRB#: HM20023438).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Previous Presentations

An abstract of this manuscript was presented as an Oral Presentation at the 18th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in Houston, Texas, USA on February 7–9, 2023.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Freudenberger, D.C., Herremans, K.M., Riner, A.N. et al. General Surgery Faculty Knowledge and Perceptions of Breast Pumping Amongst Postpartum Surgical Residents. World J Surg 47, 2092–2100 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07005-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07005-5