Abstract

Background

Attrition within surgical training is a challenge. In the USA, attrition rates are as high as 20–26%. The factors predicting attrition are not well known. The aim of this systematic review is to identify factors that influence attrition or performance during surgical training.

Method

The review was performed in line with PRISMA guidelines and registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF). Medline, EMBASE, PubMed and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for articles. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Pooled estimates were calculated using random effects meta-analyses in STATA version 15 (Stata Corp Ltd). A sensitivity analysis was performed including only multi-institutional studies.

Results

The searches identified 3486 articles, of which 31 were included, comprising 17,407 residents. Fifteen studies were based on multi-institutional data and 16 on single-institutional data. Twenty-nine of the studies are based on US residents. The pooled estimate for overall attrition was 17% (95% CI 14–20%). Women had a significantly higher pooled attrition than men (24% vs 16%, p < 0.001). Some studies reported Hispanic residents had a higher attrition rate than non-Hispanic residents. There was no increased risk of attrition with age, marital or parental status. Factors reported to affect performance were non-white ethnicity and faculty assessment of clinical performance. Childrearing was not associated with performance.

Conclusion

Female gender is associated with higher attrition in general surgical residency. Longitudinal studies of contemporary surgical cohorts are needed to investigate the complex multi-factorial reasons for failing to complete surgical residency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attrition within surgical training is a challenge, in the USA, attrition rates are as high as 20–26% [1, 2]. It is a priority to retain surgical residents to meet the increasing healthcare demand and to reduce the significant costs associated with attrition.

Discrimination in the workplace is protected by US law [3]. Age, sex, disability, race, religion, gender reassignment, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity and marriage and civil partnerships are termed ‘protected characteristics’ and relate to personal characteristics or attributes. Differential attainment refers to the differences in performance between groups with and without protected characteristics [4]. The impact of protected characteristics on attrition and performance in general surgery residency is poorly understood.

The impact of gender on attrition from general surgery residency remains unclear. Two meta-analyses reported conflicting findings regarding differences in attrition between male and female general surgery residents [5, 6]. The focus of these meta-analyses was on attrition prevalence and timing as opposed to the impact of protected characteristics. The need for further studies to clarify the role these characteristics play in attrition and performance in general surgical training was highlighted in the 2019 American College of Surgeons (ACS) statement on Harassment, Bullying and Discrimination [7]. Similarly the UK regulatory body, the General Medical Council (GMC), is working to identify areas of inequality to ensure all doctors are treated fairly regardless of protected characteristics [8].

In recent years, there has been a push to increase the diversity of medical students [9]. Consequently, there is a change in the upcoming surgeons of the future, with women now representing over a third of US surgeons in training [10]. Most studies focus on dated cohorts and do not reflect the change in the demographics of present surgical residents.

In order to reduce attrition and ensure that all trainees are facilitated to meet their maximum potential and maintain a successful surgical career, factors affecting failure to complete training or those that adversely affect performance need to be identified.

Objectives

The aim is to identify factors that influence progression through or completion of surgical training and will address the following:

-

1.

Are there any factors that predict attrition within postgraduate surgical training?

-

2.

Are there any factors that predict performance during postgraduate surgical training?

Methods

Protocol registration

This systematic review was performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) [11]. The protocol is available on the Open Science Framework (OFS) at https://osf.io/p5cby.

Eligibility criteria

The review sought to identify papers evaluating factors that affect attrition or progression through surgical training or identify factors affecting performance within surgical training. We included all types of study published as full papers with no restrictions on the language of or date of publication.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies not investigating specialty surgical trainees, e.g. consultants/faculty, non-medical staff, undergraduate training.

-

2.

Studies focused on selection into training.

Information sources, search and study selection

MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, PubMed and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched electronically using a mixture of keywords and MeSH terms. The subject strategies for databases were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid (Supplemental Fig. 1). We searched the reference lists of included studies for further eligible studies.

Two review authors (CH and JJR) independently and in duplicate performed the title and abstract screening. The full text of all eligible and potentially eligible studies were further evaluated to identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or where necessary a third reviewer opinion.

Data collection process

Two review authors (CH and JJR) independently extracted the data. If clarification was needed for any aspect of the included studies, the authors were contacted by email. The primary outcome measures were attrition and performance through training. Attrition was defined as voluntarily or involuntary discontinuation of surgical residency. Protected characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, and marital and parental status), other factors (personal, workplace/programme, educational/academic) and factors related to performance (examination performance, personality/learning style, operative volume) were extracted from each study. Publication year, country of origin, study size and population, methodology and data source were recorded.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Methodology checklists for both cohort and case–control studies were reviewed and used to critically appraise and grade the evidence of included studies. Quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [12].

Synthesis of results

The results were divided into studies that investigated factors affecting attrition and studies that focused on factors that affected performance. A random effects meta-analysis was performed to generate a pooled estimate of attrition prevalence. Two sensitivity analyses were performed including only multi-institutional studies and studies published after 2008. Between studies, heterogeneity was measured with the I2 statistic. I2 of greater than 75% was taken as a high level of heterogeneity. Random effects meta-analyses was conducted for sex. In the event of more than one study including the same population of residents, the study with the largest sample was included in the meta-analysis. Subgroup differences were tested using the z test. It was not possible to perform a meta-analysis on any other factors due to variation in outcome measurement and study design. It was also not possible to look at attrition worldwide due to the lack of non-US studies. All analyses were performed in Stata version 15 (Stata Corp LP), with a p < 0.05 significance level.

Results

Study selection

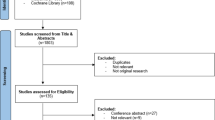

The searches identified 3486 articles (Fig. 1). The main reason for exclusion on title and abstract screening was wrong outcome or wrong population. Thirty-one studies met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Twenty-nine of the studies were from the USA, one from Pakistan and one from the UK. In regard to study quality, five studies were at high risk of bias, fifteen moderate risk and eleven low risk (Supplemental Table 1). Twenty-six studies reported attrition prevalence and were included in the meta-analysis, comprising 17,407 residents. The pooled estimate of overall attrition was 17% (95% CI 14–20%) with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 96.84%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The pooled estimate of attrition was 14% (95% CI 10–17%) on sensitivity analysis of only multi-institutional studies with greater heterogeneity (I2 = 98.10%, p = 0.00), and therefore, initial analyses are presented (Supplemental Fig. 2). After only including studies published after 2008, the overall attrition remained 17% (95% CI 13–20%, I2 = 97.06%, p = 0.00) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Attrition

Age

Two out of four studies found no association with age and attrition [1, 13] (Table 2). In the studies that found increasing age to be a risk factor for attrition, age was dichotomised to under and over 29 [14] and under and over 35 years [15] in the analysis. The positive finding in the study by Naylor [14] may be due to the outcome measure which combines attrition with failure to pass the board examination.

Gender

The pooled attrition prevalence for male residents on random effect meta-analysis was 16% (95% CI 12–20%), with significant between study heterogeneity (I2 = 95.35%, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3). The pooled attrition prevalence for women was significantly higher at 24% (95% CI 18–30%, z = -4.6832 p < 0.001), again with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 94.62%, p < 0.01). On sensitivity analysis, including only multi-intuitional studies or those published after 2008 did not significantly affect the pooled attrition of male or female residents (Supplemental Fig. 4 and 5).

Four out of 16 studies found a significantly higher attrition amongst female residents [16,17,18,19] (Table 2). One reported that women were almost twice as likely to leave training as men (OR 1.9 95% CI 1.2–3.0) [16]. A nine-year follow-up study found there were differences in attrition rate for men and women over time, with similar rates in the first year, but at four years into residency women had significantly higher rates of attrition (21.9% vs 16.3%, p = 0.05) [19]. Women also had a higher cumulative attrition (OR 1.40 95% CI 1.02–1.94) [19].

Ethnicity/race

Five studies investigated the association between race or ethnicity and attrition [1, 15, 17,18,19] (Table 2). Four studies reported that Hispanic residents were less likely to complete residency; however, 3 of these studies were based on the same population of residents [15, 17,18,19]. Therefore, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis of the data. One study found that while white race was not associated with higher completion rates across both genders (69.7% completion vs 65.8% non-completion, p = 0.34) [18], on subgroup analysis of women, white women had lower non-completion rates than non-white women (20% vs 30% p = 0.08).

Marital and parental status

None of the studies found an association between parental status and attrition [1, 13, 15]; this included two large multi-institutional studies (Table 2). Only one study found those that were married were less likely to leave training, this was a small single-institutional study of 85 residents from 1999 to 2009 [13].

Personal factors

There was no association between attrition and ‘grit’ [20, 21] social belonging [22] or motivational personality traits [23] (Table 3). Grit was defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals. The number of residents that did not complete training in these studies was small and therefore limits the power of statistical analysis. Quillin et al. reported that residents who learn by observation are more likely to leave the programme and opt for a non-surgical specialty [24].

Workplace and programme factors

Eight studies reported the impact of work place factors on failure to complete general surgery residency [1, 15, 17,18,19, 25,26,27] (Table 3). Early postgraduate year [1, 15], larger programme size [17, 18] and military programmes [18, 19] were found to be associated with higher attrition.

Educational and academic factors

Six studies investigated medical school factors affecting completion of residency [14, 17, 25, 28,29,30] (Table 3). Two studies reported an association between ABSITE score and attrition [25, 30]. Residents who felt medical school faculty were happy with their surgical careers were less likely to experience attrition [17], while those who got along well with attending surgeons during medical school had higher odds of attrition. Protective factors on the residency application were comments in the dean’s letter, participation in team sports [14] and residency interview score [30].

Performance

Six studies focused on factors that predicted performance throughout surgical residency [20, 24, 31,32,33,34] (Table 4). Performance included examination scores, operative case volume and in-training evaluations. Childrearing was not associated with operative case volume or examination performance [13]. Factors reported to affect US postgraduate surgical examination performance were learning preference [31] and faculty evaluation of clinical performance [34]. However, these studies are based on small sample sizes. The only UK-based study investigated whether postgraduate examination scores are a predictor of performance throughout UK surgical training [32]. Non-white ethnicity and examination performance were found to be independent predictors of unsatisfactory performance.

Discussion

This is the first study to report the association between protected characteristics and attrition and performance during surgical training. Overall, of the studies included in our systematic review 25 reported factors associated with progression or completion of surgical training and seven focused on factors affecting performance. The pooled attrition rate was high at 17% which causes a burden to residency programmes and existing residents. Efforts should be made to retain residents and to reduce the financial and training implications of attrition. Worryingly given the changing demographic of surgical trainees, rates of attrition were higher in women.

The limitations of this study are related to the included studies, the majority of which are conducted in a single institution which increases bias and reduces generalisability. A significant finding that limits generalisability to current surgical trainees is that fourteen of the studies include cohorts that started training over 20 years ago. During this time, training requirements and assessment processes have changed, as has the population of surgical trainees with an increase in female trainees. However, on sensitivity analysis including only studies published since 2008 did not affect the overall pooled attrition or that of attrition by gender. Nine of the included studies rely on survey data which are subject to response and recall bias. Also, as all but two of the included studies are from the USA, attrition rates and factors affecting this in other countries have not been investigated.

Attrition rates in general surgery residency remain higher than other surgical specialities [35,36,37]. In a study of Canadian surgical residents, 26.8% were considering leaving their training programme with poor work–life balance cited as the main reason [38]. This study provides clarity regarding the impact of resident gender on attrition after two previous meta-analyses reported differing findings [5, 6]. We found a significantly higher attrition rate for female residents on pooled meta-analysis. This is consistent with a meta-analysis that found female residents had a 25% pooled attrition rate compared to 15% of men [6]. This finding is not unique to general surgery; higher attrition rates for female residents have also been reported in neurosurgery [39, 40] and orthopaedics [36].

The findings regarding the impact of Hispanic ethnicity and attrition require further investigation. As three of the four studies reporting higher attrition amongst Hispanic residents are based on the same population, it is not possible to make firm conclusions. However, higher attrition for Hispanic residents has been reported across other specialities. A 2019 study of US emergency medicine residents found that a significantly greater proportion of Hispanic residents left the programme compared to white residents [41]. They also reported a higher rate of dismissal for Hispanic residents compared to Asian and white residents. The fact that Hispanic residents are an underrepresented group in postgraduate medicine may result in less access to role models they can identify with which may impede residency satisfaction [42]. Residents of non-white ethnicity were less likely to feel they fit in their residency programme which may partly explain the higher attrition [43].

Half of the studies found that age is associated with increased attrition; in both of these studies, age was dichotomised to an arbitrary number which may influence the findings [14, 15]. All three of the studies that analysed the effect of parental status find no increased rates [1, 13, 15]. These findings are reassuring given the increasing number of female surgical trainees and increasing acceptance of childrearing during residency. One study found that while the perception of negative attitudes towards pregnancy during training has decreased over time, some stigma persists [44]. It additionally reported that those who had graduated from medical school more recently were more likely to have a pregnancy during training than their older counterparts. The finding that childrearing does not affect attrition or performance should encourage residency programmes to develop clear guidance regarding parental leave, as in a recent study only 3.8% of residents were able to correctly identify the American Board of Surgery policy and felt unsupported [45].

The studies that focused on performance vary greatly in design and outcome measure. As with attrition, there was no association between childrearing or ‘grit’ and performance. The definition of performance is not uniform across studies and this limits interpretation. Four of these studies are based on populations commencing surgical residency more than 20 years ago, in one case from 1967. A 2017 study outlines the different assessment tools used during residency and highlights the lack of effective tools to measure competence [46]. Further studies investigating the relationship between attrition and performance using standardised measures of performance are warranted.

Conclusion

Female residents have higher attrition than male residents in general surgery. Marital and parental status are not associated with increased risk of attrition in general surgery residency. Longitudinal studies of contemporary surgical cohorts are needed to investigate the complex and multi-factorial reasons for failing to complete surgical residency internationally.

References

Yeo H et al (2010) A national study of attrition in general surgery training: which residents leave and where do they go? Ann Surg 252(3):529–534 (discussion 534-6)

Kwakwa F, Jonasson O (1999) Attrition in graduate surgical education: an analysis of the 1993 entering cohort of surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg 189(6):602–610

United States Congress (2019) H.R.5-Equality Act, [cited 2020 23/01/2020]; Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5

Regan de Bere S, Nunn S, Nasser M (2015) Understanding differential attainment across medical training pathways: a rapid review of the literature. [cited 2020 03/03/2020]; Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/GMC_Understanding_Differential_Attainment.pdf_63533431.pdf

Shweikeh F et al (2018) Status of resident attrition from surgical residency in the past, present, and future outlook. J Surg Educ 75(2):254–262

Khoushhal Z et al (2017) Prevalence and causes of attrition among surgical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg 152(3):265–272

American College of Surgeons (2019) Statement on harassment, bullying, and discrimination. [cited 2020 03/03/2020]; Available from: https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/117-harassment

General Medical Council (2019) The GMC asks doctors for diversity data to help ensure fair regulation. [cited 2020 03/03/2020]; Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/doctors-diversity-data

Liaison Committee on Medical Education (2009) Liaison committee on medical education (LCME) standards on diversity. [cited 2019 18/10/2019]; Available from: https://health.usf.edu/~/media/Files/Medicine/MD%20Program/Diversity/LCMEStandardsonDiversity1.ashx?la=en

Bruce AN et al (2015) Perceptions of gender-based discrimination during surgical training and practice. Med Educ Online 20(1):25923

Moher D et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Wells G et al (2020) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [cited 2020 04/01/2020]; Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Brown EG et al (2014) Pregnancy-related attrition in general surgery. JAMA Surg 149(9):893–897

Naylor RA, Reisch JS, Valentine RJ (2008) Factors related to attrition in surgery residency based on application data. Arch Surg 143(7):647–651 (discussion 651-2)

Sullivan MC et al (2013) Surgical residency and attrition: defining the individual and programmatic factors predictive of trainee losses. J Am Coll Surg 216(3):461–471

Gifford E et al (2014) Factors associated with general surgery residents’ desire to leave residency programs: a multi-institutional study. JAMA Surg 149(9):948–953

Symer MM et al (2018a) Impact of medical school experience on attrition from general surgery residency. J Surg Res 232:7–14

Yeo HL et al (2017) Who makes it to the end?: A novel predictive model for identifying surgical residents at risk for attrition. Ann Surg 266(3):499–507

Yeo HL et al (2018) Association of time to attrition in surgical residency with individual resident and programmatic factors. JAMA Surg 153(6):511–517

Burkhart RA et al (2014) Grit: a marker of residents at risk for attrition? Surgery 155(6):1014–1022

Salles A et al (2017) Grit as a predictor of risk of attrition in surgical residency. Am J Surg 213(2):288–291

Salles A et al (2019) Social belonging as a predictor of surgical resident well-being and attrition. J Surg Educ 76(2):370–377

Symer MM et al (2018b) The surgical personality: does surgery resident motivation predict attrition? J Am Coll Surg 226(5):777–783

Quillin IRC et al (2013) How residents learn predicts success in surgical residency. J Surg Educ 70(6):725–730

Yaghoubian A et al (2012) General surgery resident remediation and attrition: a multi-institutional study. Arch Surg 147(9):829–833 ((Chicago, Ill.: 1960))

Everett CB et al (2007) General surgery resident attrition and the 80-hour workweek. Am J Surg 194(6):751–757

Leibrant TJ et al (2006) Has the 80-hour work week had an impact on voluntary attrition in general surgery residency programs? J Am Coll Surg 202(2):340–344

Falcone JL (2014) Home school dropout: a twenty-year experience of the matriculation of categorical general surgery residents. Am Surg 80(2):216–218

Farley DR, Cook JK (2001) Whatever happened to the general surgery graduating class of 2001? Curr Surg 58(6):587–590

Alterman DM et al (2011) The predictive value of general surgery application data for future resident performance. J Surg Educ 68(6):513–518

Kim JJ et al (2015) Program factors that influence american board of surgery in-training examination performance: a multi-institutional study. J Surg Educ 72(6):e236–e242

Scrimgeour D et al (2018) Does the intercollegiate membership of the royal college of surgeons (MRCS) examination predict “on-the-job” performance during UK higher specialty surgical training? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 100(8):669–675

Hayward CZ, Sachdeva A, Clarke JR (1987) Is there gender bias in the evaluation of surgical residents? Surgery 102(2):297–299

Wade TP, Andrus CH, Kaminski DL (1993) Evaluations of surgery resident performance correlate with success in board examinations. Surgery 113(6):644–648

Meyerson J, Yang M, Pearson G (2016) Attrition in plastic surgery residencies. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 4(10):e1102

Bauer JM, Holt GE (2016) National orthopedic residency attrition: who is at risk? J Surg Educ 73(5):852–857

Prager JD, Myer CMT, Myer CM (2011) 3rd, Attrition in otolaryngology residency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145(5):753–754

Adams S et al (2017) Attitudes and factors contributing to attrition in Canadian surgical specialty residency programs. Can J Surg 60(4):247–252

Renfrow JJ et al (2016) Positive trends in neurosurgery enrollment and attrition: analysis of the 2000–2009 female neurosurgery resident cohort. J Neurosurg 124(3):834–839

Lynch G et al (2015) Attrition rates in neurosurgery residency: analysis of 1361 consecutive residents matched from 1990 to 1999. J Neurosurg 122(2):240–249

Lu DW et al (2019) Why residents quit: national rates of and reasons for attrition among emergency medicine physicians in training. West J Emerg Med 20(2):351–356

Yehia BR et al (2014) Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: a mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ 14:26

Wong RL et al (2013) Race and surgical residency: results from a national survey of 4339 US general surgery residents. Ann Surg 257(4):782–787

Turner PL et al (2012) Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg 147(5):474–479

Altieri MS et al (2019) Perceptions of surgery residents about parental leave during training. JAMA Surg 154(10):952–958

Sandher S, Gibber M (2017) Assessing surgical residents; challenges and future options. MedEdPublish 6(4):11–19

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hope, C., Reilly, JJ., Griffiths, G. et al. Factors Associated with Attrition and Performance Throughout Surgical Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg 45, 429–442 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05844-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05844-0