Abstract

Background

Day surgical procedures are increasing both in Sweden and internationally. Day surgery patients prepare for and handle their recovery on their own at home. The aim of this study was to investigate patients’ preoperative mental and physical health and its association with the quality of their recovery after day surgery.

Method

This was a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Data were collected at four-day surgery units in Sweden. Health-related quality of life was measured using the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey, and postoperative recovery was assessed using the Swedish web version of the Quality of Recovery (SwQoR) scale.

Result

This study included 756-day surgery patients. A low, compared with a high, preoperative mental component score was associated with poorer recovery as shown by responses to 21/24 and 22/24 SwQoR items, respectively, on postoperative days (PODs) 7 and 14. A low compared with a high preoperative physical component score was associated with poorer recovery in 18/24 SwQoR items on POD 7 and 13/24 on POD 14.

Conclusion

A clear message from this study is for surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses to consider the fact that postoperative recovery largely depends on patients’ preoperative mental and psychical status. A serious attempt must be made, as a part of the routine preoperative assessment, to assess and document not only the physical but also the mental status of patients undergoing anaesthesia and surgery.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT0249219.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

All surgical procedures are followed by postoperative recovery including patients’ increasing control over physical, psychological, social and habitual functions [1]. Patients about to undergo day surgery have reported that they prepare themselves, to a greater or lesser extent, to focus on their recovery after surgery. For example, they inform themselves about their condition, prepare their household, inform their next of kin and do more exercise [2, 3]. Barriers to a good postoperative recovery have been reported to be preoperative anxiety, which in other research was associated with higher postoperative pain scores in the early recovery phase in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy [4], lower limb amputation [5] and septoplasty [6].

Preoperative physical and psychological functions such as depression have been reported to increase the risk for postoperative complications in patients undergoing lumbar fusion [7]. Preoperative depression can also increase the risk of postoperative late mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery [8, 9] and decrease the quality of recovery in patients undergoing spine surgery [10]. Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery with poor preoperative quality of life had an increased risk of moderate to severe postoperative adverse events. Adverse events were found to be independent of the surgical approach (laparoscopy vs. open surgery of endometriosis), age, body mass index (BMI) and medical comorbidity [11]. It should be noted that earlier studies have mainly investigated isolated symptoms and not the whole spectrum of symptoms and discomfort that can be experienced in the postoperative recovery process and while undergoing minor surgery. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate patients’ preoperative mental and physical health, and its association with the quality of their recovery after day surgery.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This observational study is a secondary analysis of a multi-centre, two-group, parallel, single-blind randomized controlled trial conducted from October 2015 to July 2016 at four-day surgery departments in Sweden [12]. The randomized controlled trial’s primary outcome was the cost-effectiveness of using the Recovery Assessment by Phone Points (RAPP) mobile app for follow-up, compared with no follow-up with RAPP (i.e. providing standard care), after day surgery. The RAPP app is a digital follow-up tool that measures quality of recovery using the Swedish web version of the Quality of Recovery (SwQoR) scale. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration (6th revision) and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Uppsala/Örebro (2015/262). The trial was registered with the US National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry: NCT02492191.

Sample selection

Inclusion criteria were ≥ 18 years old, undergoing day surgery, having access to a mobile phone and being able to understand written and spoken Swedish. Exclusion criteria were alcohol and/or drug abuse, having a visual or cognitive impairment, and undergoing a surgical abortion.

Questionnaires

To assess mental and physical health, Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) was used. SF-36 consists of 36 items grouped into eight multi-item scales that measure physical function, role function, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role and mental health [13, 14]. All scales are scored from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better health status. Two summary scores are calculated, the Physical Component Score (PCS) and the Mental Component Score (MCS), reflecting overall physical and mental health status, respectively [14]. The summary scores are constructed and standardized in relation to the norm population [15]. A summary mean score of 50 corresponds to the distribution of scores in the general US population in which scores < 50 indicates poor physical or mental health compared with the general population [15, 16].

Quality of recovery was assessed with the SwQoR, a multi-item questionnaire including 24 items measuring different symptoms/discomfort related to surgery and anaesthesia. The patients rate the items on an 11-point numerical rating scale from 0 = “none of the time” to 10 = “all of the time”. The global score for the SwQoR ranges between 0 (excellent postoperative recovery) and 240 (poor postoperative recovery). A patient is deemed to have had good postoperative recovery if they score < 31 on postoperative day (POD) 7 and < 21 on POD 14 [17]. The SwQoR has been psychometrically tested and has been found to be valid for assessing postoperative recovery [18].

Data collection

Preoperatively written information about the study was sent out to patients about to undergo day surgery, together with information about the planned surgery. At each of the day surgery departments, a research nurse was responsible for the inclusion of participants. Oral information was provided preoperatively on the day of surgery, and oral and written consent was obtained from all participants. Preoperatively, on the day of surgery, the participants answered the SF-36; at 1 and 2 weeks postoperatively they answered the SwQoR either digitally via the RAPP or by submitting their answers on a paper-based form. An earlier study has shown equivalence between the paper and web version of the SwQoR scale [19].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, type of anaesthesia and surgery, SwQoR score, and preoperative MCS and PCS. Guided by earlier studies, means and standard deviations (SDs) are used for the SwQoR scores [17, 18, 20]. The differences in sex, ASA classification, type of anaesthesia and surgery, and SwQoR results for PODs 7 and 14 between the patients in the low versus high preoperative MCS and PCS categories were analysed with Chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney U tests. A multivariable stepwise linear regression analysis of factors showed associations with preoperative MCS and PCS, accounting for age, sex, type of surgery and anaesthesia, ASA classification and SwQoR scores on days 7 and 14.

A p value of < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Office Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA, USA).

Results

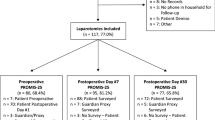

The main study of this project [21] included 1027 patients, 756 (73.6%) of whom completed the SwQoR scale on POD 7 (Table 1). The mean MCS was 48.3 (SD 10.8) and the mean PCS 44.9 (SD 10.3). The majority of the patients reported a high MCS, i.e. > 50, n = 452 (69.8%), and a low PCS, pre-surgery, i.e. < 50, n = 478 (63.2%).

Mental health

Significantly more women than men had a poor MCS, 197/435 (45.3%) versus 107/321 (33.3%), p = 0.001. There was also a difference in age, irrespective of sex, seen as a significantly lower mean age in those suffering from poor mental health, compared with those having good mental health, 44 years (SD 15.1) versus 47 years (SD 14.8), p = 0.006. No differences were seen in ASA classification, type of surgery or anaesthesia, duration of surgery and duration of stay at the post-anaesthesia care unit.

There was a significantly lower quality of recovery (SwQoR), i.e. a higher rating of symptoms/discomfort, in 21/24 items on POD 7 and 22/24 items on POD 14 in patients with a low MCS, pre-surgery, compared with those with a high MCS.

This difference was significant also for the global SwQoR score (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Both quality of recovery and sex were independently associated with preoperative MCSs: the SwQoR score for POD 7 was R = 0.412, R2 = 0.170 (standard error = 9.824; p < 0.001); the SwQoR score for POD 14 was R = 0.458, R2 = 0.290 (standard error = 9.607; p < 0.001); for sex, R = 0.441, R2 = 0.194 (standard error = 9.688; p < 0.001).

Physical health

Those suffering from poor preoperative physical health had a significantly higher mean age compared with those in good physical health, 46 years (SD 14.8) versus 44 years (SD 15.1), p = 0.004. There was also a difference in type of surgery, with a higher proportion of patients with a poor preoperative PCS undergoing hand (71.8%) and orthopaedic (82.8%) surgery compared with general (44.2%), gynaecological (28%) and ENT surgery (38.8%), p < 0.001. No differences were seen in sex, ASA classification, type of anaesthesia, duration of surgery and duration of stay at the post-anaesthesia care unit.

There was significantly lower quality of recovery (SwQoR), i.e. a higher rating of discomfort, in 18/24 items on POD 7 and in 13/24 items on POD 14 in patients with a poor preoperative PCS compared with patients with a high preoperative PCS. Also, the global SwQoR score differed significantly (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The SwQoR score on POD 7 and type of surgery were independently associated with the preoperative PCS. The SwQoR score for POD 7 was R = 0.422, R2 = 0.178 (standard error = 9.381; p < 0.001); for type of surgery, R = 0.355, R2 = 0.126 (standard error = 9.662; p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our results show that even in a relatively healthy population undergoing minor surgery, preoperative mental and physical health has a great impact on late postoperative recovery. It can also be discussed if the individual changes and differences comparing cohorts and over time are of minimal meaningful clinical significance (most having < 2) outside of measures related to muscle pain, surgical wound pain, and difficulty in urination. Minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) have not been determined for SwQoR. However, Myles et al. [22] have found that perioperative interventions that result in a change of 6.3 for the QoR-40, including 40 items, signify a clinically important improvement or deterioration. In present study, the differences in global SwQoR on POD 7 between low (43.02) and high mental (22.97) health was 20.05 which could be interpreted as a clinical important differences. Aspari and Lakshman state that a factor that is most commonly overlooked is the patient’s psychological status and its influence on postoperative recovery [23] as well as the number of people suffering from mental health problem has increase over the years [24]. Despite this, it is hard to find studies examining postoperative recovery of day surgery patients and its relation to poor preoperative mental health. Nevertheless, our findings are supported by other studies investigating isolated symptoms such as postoperative pain in patients undergoing major surgery that report an association between poor preoperative mental status and increased rate of postoperative complications [7], [25], adverse events [11], mortality [8, 9], opioid use and risk of chronic use [7] and pain [4,5,6, 23, 26].

We found that women had significantly higher incidence of poor mental health compared with men. Women are two times as likely as men to experience depression and this sex difference is robust, well documented and cross-cultural [27]. However, findings about differences and similarities between the sexes regarding preoperative anxiety are somewhat different [28]. Differences between the sexes are small and, in many cases, trivial. The stereotype that women are the emotional ones and that there are large sex differences in emotions such as fear and anxiety still exists [29]. Gender similarities in day surgery patients have been found in preoperative emotional stability [30] and postoperative recovery [31].

In the present study, we also found an association between poor preoperative physical status and low quality of postoperative recovery. We further found that the mean age was higher in those suffering from poor preoperative physical health compared with those having good preoperative physical health. There was a difference in type of surgery, seen as a higher proportion of patients with poor physical health preoperatively undergoing hand and orthopaedic surgery. These results are not so surprising though the negative impact on physical health is an indication for these types of surgeries. To optimize the postoperative recovery, it has been recommended to assess the physical activity level preoperatively for prognostic reasons [32]. However, there is no consensus regarding the effect of a physical exercise training programme prior to surgery (prehabilitation) and whether it has beneficial effects on postoperative outcome [32,33,34].

The recovery process is dependent on much more than type of surgery and anaesthesia, such as mental and psychical status. It is therefore of great importance to identify patients with poor preoperative mental and physical health in order to optimize their postoperative recovery. Postoperative recovery can be divided into three phases: (1) early recovery, which starts when the patient leaves the operating room; (2) intermediate recovery, when the patient is still cared for at the day surgery unit but is not monitored as closely as in phase I; and (3) late recovery, which starts when the patient is discharged from the day surgery unit and continues until they have regained their usual function and activity [35]. It seems, however, that a fourth phase should be included: phase 0, the pre-recovery phase in which identification of and optimization for vulnerable patients should be implemented [3]. Our suggestion is supported by Wetsch et al. who found that day surgery patients experienced significantly higher levels of preoperative stress and anxiety compared with inpatients [36]. They recommend that the stress and anxiety profile of patients needs to be assessed regarding suitability for day surgery and that surgeons should perform a short screening procedure to test for preoperative anxiety [36].

The SwQoR scale, used in present study, assesses symptoms and discomfort that are present in the recovery process [18]. The items in the SwQoR have been validated by surgeons, anaesthesiologists, nurses and day surgery patients and have been found to be relevant for assessing postoperative recovery [19]. To assess mental and physical health, the well-known and validated SF-36 questionnaire was used [13, 14]. It is the investment in the development of such questionnaires that allows formal measurement and monitoring of health-related variables to generate empirical data and thus to identify, develop, implement and evaluate appropriate interventions [37].

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations such as that we did not ask our participants preoperatively whether they had been diagnosed with any mental illness or whether they were taking any anxiolytic drugs. Furthermore, the inclusion criterion of ability to understand written and spoken Swedish was a limitation, as was the sample size, which was calculated for the primary outcome, cost-effectiveness [21]. We are aware of these limitations; still, our results add valuable information regarding preoperative physical and mental health and its association with postoperative recovery, an area that needs to be further investigated in future studies.

Conclusion

A clear message from this study is for surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses to consider the fact that postoperative recovery does importantly depend on patients’ preoperative mental and psychic status. A serious attempt must be made to assess and document, not only the physical status, but also the mental status of patients undergoing surgery and anaesthesia as a part of the routine preoperative status assessment. Based on the status, formal counselling must be instituted to prepare the patient, mentally and physically, even before a minor surgical intervention, in order to optimize their postoperative recovery. Furthermore, systematic assessment of postoperative recovery including the whole spectrum of symptoms and discomfort experienced, using well-validated questionnaires, is important.

References

Allvin R, Berg K, Idvall E, Nilsson U (2007) Postoperative recovery: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 57(5):552–558

Berg K, Arestedt K, Kjellgren K (2013) Postoperative recovery from the perspective of day surgery patients: a phenomenographic study. Int J Nurs Stud 50(12):1630–1638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.05.002

Dahlberg K, Jaensson M, Nilsson U, Eriksson M, Odencrants S (2018) Holding it together—a qualitative study of patients’perspectives on postoperative recovery when using an e-assessed follow-up. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6(5):10387. https://doi.org/10.2196/10387

Ali A, Altun D, Oguz BH, Ilhan M, Demircan F, Koltka K (2014) The effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Anesth. 28(2):222–227

Raichle KA, Osborne TL, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Smith DG, Robinson LR (2015) Preoperative state anxiety, acute postoperative pain, and analgesic use in persons undergoing lower limb amputation. Clin J Pain 31(8):699–706

Ocalan R, Akin C, Disli Z, Kilinc T, Ozlugedik S (2015) Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing septoplasty. B-ent 11(1):19–23

O’Connell C, Azad TD, Mittal V, Vail D, Johnson E, Desai A et al (2018) Preoperative depression, lumbar fusion, and opioid use: an assessment of postoperative prescription, quality, and economic outcomes. Neurosurg Focus 44(1):E5

Takagi H, Ando T, Umemoto T, Group A (2017) Perioperative depression or anxiety and postoperative mortality in cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Vessels 32(12):1458–1468

Stenman M, Holzmann MJ, Sartipy U (2016) Association between preoperative depression and long-term survival following coronary artery bypass surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 222:462–466

Dunn LK, Durieux ME, Fernández LG, Tsang S, Smith-Straesser EE, Jhaveri HF, et al (2018) Influence of catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression on in-hospital opioid consumption, pain, and quality of recovery after adult spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 28(1):119–126

Baker J, Janda M, Gebski V, Forder P, Hogg R, Manolitsas T et al (2015) Lower preoperative quality of life increases postoperative risk of adverse events in women with endometrial cancer: results from the LACE trial. Gynecol Oncol 137(1):102–105

Nilsson U, Jaensson M, Dahlberg K, Odencrants S, Grönlund Å, Hagberg L et al (2016) RAPP, a systematic e-assessment of postoperative recovery in patients undergoing day surgery: study protocol for a mixed-methods study design including a multicentre, two-group, parallel, single-blind randomised controlled trial and qualitative interview studies. BMJ Open 6(1):e009901

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE Jr (1995) The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey—I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 41(10):1349–1358

Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M (2001) Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Qual Life Res 10(5):395–404

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller S (1994) SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales. a user’s manual

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Taft C (2002) SF-36 Hälsoenkät: Svensk manual och tolkningsguide: Sahlgrenska sjukhuset, Sektionen för vårdforskning

Jaensson M, Dahlberg K, Eriksson M, Nilsson U (2017) Evaluation of postoperative recovery in day surgery patients using a mobile phone application: a multicentre randomized trial. Br J Anaesth 119(5):1030–1038

Nilsson U, Dahlberg K, Jaensson M (2017) The Swedish Web version of the quality of recovery scale adapted for use in a mobile app: prospective psychometric evaluation study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 5(12):e188

Dahlberg K, Jaensson M, Eriksson M, Nilsson U (2016) Evaluation of the Swedish Web-Version of Quality of Recovery (SwQoR): secondary step in the development of a mobile phone app to measure postoperative recovery. JMIR Res Protoc 5(3):e192

Hälleberg-Nyman M, Nilsson U, Dahlberg K, Jaensson M (2018) The association between functional health literacy and postoperative recovery, healthcare contacts and health related quality of life among patients undergoing day surgery. JAMA Surg 153(8):1–8

Dahlberg K, Philipsson A, Hagberg L, Jaensson M, Hälleberg-Nyman M, Nilsson U (2017) Cost-effectiveness of a systematic e-assessed follow-up of postoperative recovery after day surgery: a multicentre randomized trial. Br J Anaesth 119(5):1039–1046

Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, Chew C, MacDonald N, Dennis A (2016) Minimal clinically important difference for three quality of recovery scales. Anesthesiology 125(1):39–45

Aspari AR, Lakshman K (2018) Effects of pre-operative psychological status on post-operative recovery: a prospective study. World J Surg 42(1):12–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4169-2

Burki T (2018) Increase in detentions in the UK under the Mental Health Act. Lancet Psychiatr 5(11):878

Kugelman D, Qatu A, Haglin J, Konda S, Egol K (2018) Impact of psychiatric illness on outcomes after operatively managed tibial plateau fractures (OTA-41). J Orthop Trauma 32(6):e221–e225

Vaughn F, Wichowski H, Bosworth G (2007) Does preoperative anxiety level predict postoperative pain? AORN J 85(3):589–604

Moieni M, Irwin MR, Jevtic I, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Eisenberger NI (2015) Sex differences in depressive and socioemotional responses to an inflammatory challenge: implications for sex differences in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 40(7):1709

Cevik B (2018) The evaluation of anxiety levels and determinant factors in preoperative patients. Int J Med Res Health Sci 7(1):135–143

Hyde JS (2014) Gender similarities and differences. Ann Rev Psychol 65:373–398

Nilsson U, Berg K, Unosson M, Brudin L, Idvall E (2009) Relation between personality and quality of postoperative recovery in day surgery patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol 26(8):671–675. https://doi.org/10.1097/eja.0b013e32832a9845

Jaensson M, Dahlberg K, Nilsson U (2018) Sex similarities in postoperative recovery and health care contacts within 14 days with mHealth follow-up: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Perioper Med 1(1):e2

Onerup A, Angerås U, Bock D, Börjesson M, Olsén MF, Gellerstedt M et al (2015) The preoperative level of physical activity is associated to the postoperative recovery after elective cholecystectomy–a cohort study. Int J Surg 19:35–41

Moran J, Guinan E, McCormick P, Larkin J, Mockler D, Hussey J et al (2016) The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 160(5):1189–1201

O’doherty A, West M, Jack S, Grocott M (2013) Preoperative aerobic exercise training in elective intra-cavity surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 110(5):679–689

Ead H (2006) From Aldrete to PADSS: reviewing discharge criteria after ambulatory surgery. J Perianesth Nurs 21(4):259–267

Wetsch WA, Pircher I, Lederer W, Kinzl J, Traweger C, Heinz-Erian P et al (2009) Preoperative stress and anxiety in day-care patients and inpatients undergoing fast-track surgery. Br J Anaesth 103(2):199–205

Wright JP, Edwards GC, Goggins K, Tiwari V, Maiga A, Moses K et al (2018) Association of health literacy with postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. JAMA surgery. 153(2):137–142

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by FORTE (the Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Health Care), Grant No. 2013-4765, and the Vetenskapsrådet (the Swedish Research Council), Grant No. 2015-02273.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsson, U., Dahlberg, K. & Jaensson, M. Low Preoperative Mental and Physical Health is Associated with Poorer Postoperative Recovery in Patients Undergoing Day Surgery: A Secondary Analysis from a Randomized Controlled Study. World J Surg 43, 1949–1956 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-04995-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-04995-z