Abstract

Background

Risk assessment strategies, such as using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, attempt to identify surgical high-risk patients. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is a biomarker reflecting overall systemic inflammation and immune activation, and it could potentially improve the identification of high-risk surgical patients.

Methods

We included patients acutely admitted to the emergency department who subsequently underwent surgery within 90 days of admission. Patients were stratified into low-risk or high-risk groups, according to ASA classification (ASAlow: ASA I–II; ASAhigh: ASA III–VI) and suPAR level, measured at admission (suPARhigh above and suPARlow below 5.5 ng/ml), respectively. Pre-specified complications were identified in national registries and electronic medical records. The association between ASA classification, suPAR level, CRP and the rate of postoperative complications was analyzed with logistic regression and Cox regression analyses, estimating odds ratios and hazard ratios (HRs).

Results

During 90-day follow-up from surgery, 31 (7.0%) patients died and 158 (35.6%) patients had postoperative complications. After adjusting for age, sex, and ASA classification, the HR for 90-day postoperative mortality was 2.5 (95% CI 1.6–4.0) for every doubling of suPAR level. suPAR was significantly better than CRP at predicting mortality and all complications (P = 0.0036 and P = 0.0041, respectively). Combining ASA classification and suPAR level significantly improved prediction of mortality and the occurrence of a postoperative complication within 90 days after surgery (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Measuring suPAR levels in acutely admitted patients may aid in identifying high-risk patients and improve prediction of postoperative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Continuously optimizing treatment of surgical patients has reduced the incidence of postoperative complications, but more than one third of in-hospital complications remain related to surgical procedures [1], although these are often preventable [2].

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification is a simple six-point scale used in the preoperative setting to assess the surgical patients’ overall physical status [3]. The ASA classification has been shown to be a good predictor of mortality and other complications after surgery [4,5,6,7,8,9]. In many countries, the ASA classification remains the only preoperative risk assessment tool used systematically, even though it was never intended as a risk assessment tool [10].

Adding biomarkers to the preoperative risk assessment has shown possible advantages in predicting specific postoperative complications [11,12,13]. One biomarker with potential as a risk marker for surgical patients [14, 15] is the soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR). suPAR is the soluble form of uPAR, a surface receptor expressed on immune cells, endothelial cells, and cancer cells. In both medical and surgical patients, suPAR levels are correlated with systemic inflammation and immune activation [16], and it is a risk marker associated with mortality [17,18,19,20], duration of hospital stay, Charlson Comorbidity Index [18, 20], and a variety of acute and chronic conditions, such as chronic kidney disease [21], pneumonia [14], prosthetic joint infection [15], cancer, noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease [17]. Whether the broadly applicable and nonspecific biomarker suPAR can add predictive value to existing preoperative risk assessment has, to our knowledge, not previously been investigated.

We hypothesized that suPAR could add predictive value to the existing preoperative risk assessment of surgical patients. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine whether the suPAR level measured at admission to the emergency department could add predictive value to the ASA score in acutely admitted patients undergoing surgical procedure within 90 days of admission.

Methods

Study participants

This study is a sub-group analysis of the prospective observational study, TRIAGE, which included 6005 acute surgical and medical admissions at North Zealand Hospital, Denmark, between September 5 and December 6, 2013 [22]. Patients were included consecutively. Admission, and thereby inclusion in the study, was defined as referral to a bed and blood samples drawn in the ED. Obstetric patients and patients ≤ 17 years were not included due to direct admission to the Department of Obstetrics and the Pediatric ED, respectively. Patients deemed eligible for this study had surgical intervention within 90 days of admission.

Data collection

Data from the TRIAGE study database were supplemented with information about surgery obtained by reviewing electronic medical records. Surgical procedures were registered, coded according to the Danish National Healthcare Classification System (SKS), to assess surgical specialty and the type of surgical procedure. Surgical procedures were defined as: Minor, e.g., diagnostic laparoscopy, arthroscopy, inguinal hernia repair, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with papillotomy; moderate, e.g., cholecystectomy, primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty, minor resection of gastrointestinal tract, laparoscopic gastrointestinal procedure; major, e.g., trauma surgery, major bowel resection, major orthopedic surgery, and spinal reconstruction. ASA classification was extracted from the Danish Anesthesia Database (DAD) along with information about smoking, alcohol consumption, and body mass index (BMI), and information about vital status at follow-up was retrieved from the Civil Registration System, using the patients’ unique personal identification numbers.

suPAR analysis

Blood samples were drawn from all patients at admission, and EDTA plasma was stored at − 80 °C until later measurement. suPAR levels were measured using the suPARnostic® AUTO flex ELISA (ViroGates A/S, Denmark) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

ASA classification

Prior to surgery all patients were classified by an anesthesiologist into six different categories, according to their physical status [3, 23, 24].

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was mortality within 90 days after surgery. The secondary endpoints were postoperative complications within 90 days after surgery defined as in the SURPAS studies [25,26,27], with the inclusion of atelectasis and ileus, resulting in 22 possible postoperative complications.

Analysis and statistics

Patients were stratified into groups according to suPAR tertiles and ASA classification. A binary classification of suPAR level and ASA classification was constructed. The 1st and 2nd suPAR tertiles were classified as suPARlow (n = 297, suPAR ≤ 5.5 ng/ml), and patients in the 3rd tertile were classified as suPARhigh (n = 147, suPAR > 5.5 ng/ml). Patients were distributed unequally in ASA categories (ASA I: 148, ASA II: 179, ASA III: 110, ASA IV: 6, and ASA V: 1) patients with an ASA classification ≤ II were classified as ASAlow (n = 327) and patients with an ASA classification ≥ III were classified as ASAhigh (n = 117). This stratification of suPAR level and ASA classification resulted in comparable groups sizes.

Continuous data are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD), and categorical data are presented as n (%). Baseline characteristics were compared using Student’s t test and Chi-square test. Interrater agreement was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) presented in forest plots. Similarly, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI for log2-transformed suPAR levels or log10-transformed CRP levels. Postoperative mortality within 90 days is presented in Kaplan–Meier plots for suPAR level and ASA classification. Predictive capabilities of ASA classification and suPAR level, regarding any endpoint, are presented in area under the curve (AUC). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Graphs were created with GraphPad Prism 7.02.197 (GraphPad software) and R 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise guide 7.12 (SAS Institute) and R 3.2.3.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to Danish legislation, and it was approved by the Danish Data Protection agency (ref. no. 2007-58-0015).

Consent

Regarding consent from patients, formal ethical approval was not necessary for this study. The TRIAGE study compiled all data in a central server. All patients were pseudo-anonymized, but with a unique patient number. Patient data could afterward be cross referenced with Danish registries. This procedure is in accordance with ethical regulations.

Results

Baseline characteristics

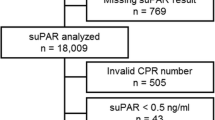

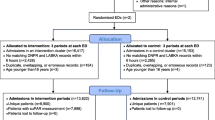

The TRIAGE study included 5302 acutely admitted patients (6005 admission). Of these, 697 (13.2%) had any surgical intervention registered within 90 days after admission and were included in the current study. Exclusion criteria were: no suPAR measurement (n = 45), patients admitted as surgical patients, but received no surgical intervention (n = 151) and no ASA classification registered (n = 57). The final population comprised 444 patients (8.4%).

In the final study population, the mean age was 61 years (SD 20.9) (Table 1). Mean suPAR level was 5.3 ng/ml (SD 3.0). The 444 surgical interventions included general surgery (n = 184, 41.4%), orthopedic surgery (n = 184, 41.4%), and other (n = 76, 17.2%), which covered urologic, gynecologic, and cardiovascular procedures.

Patients in suPARhigh and ASAhigh were older, had higher rates of various comorbidities, were more frequently smokers, had higher triage level at admission, received a higher degree of home care, underwent larger surgical interventions, and presented more frequently with preoperative SIRS/sepsis compared with suPARlow and ASAlow, respectively (Table 1).

High ASA classification and high suPAR level are associated with endpoints

Within 90 days after surgery, 31 (7.0%) patients had died, and a total of 158 (35.6%) patients had a postoperative complication (Table 2).

Patients in suPARhigh and ASAhigh had significantly higher rates of mortality, reoperation, urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, sepsis, surgical site infection (SSI), and transfusion compared to suPARlow and ASAlow, respectively (Table 2).

Kaplan–Meier plots illustrate the increased risk of postoperative mortality in all surgical specialties combined for patients with high ASA classification or suPAR level (Fig. 1).

Kaplan–Meier plot showing 90 days postoperative survival in surgical patients stratified by a ASA classification I–III+ and b suPAR levels in tertiles. Mortality rates in groups, n (%): a ASA I: 0 (0%), ASA II: 6 (19%), and ASA III+: 25 (81%). b suPAR tertile 1: 0 (0%) with a mean suPAR level of 3.14 ng/ml (SD 0.47), suPAR tertile 2: 4 (13%) with a mean suPAR level of 4.62 ng/ml (SD 0.51), and suPAR tertile 3: 27 (87%) with a mean suPAR level of 8.21 ng/ml (SD 3.65)

Univariate ORs for all endpoints were significantly higher in suPARhigh and ASAhigh compared to suPARlow or ASAlow, respectively (Fig. 2). For the following endpoints, OR (95% CI) were highly significant (P < 0.0001) for suPAR level and ASA classification, respectively: sepsis 10.8 (4.0–29.1) and 10.0 (4.1–24.2); mortality 16.5 (5.7–48.3) and 14.3 (5.7–35.8); and for any endpoint 4.0 (2.6–6.1) and 5.3 (3.3–8.3). The association between high suPAR level and mortality, sepsis, reoperation, or any endpoint remained significant after adjusting for sex, age, and ASA classification (Fig. 2). The association between high ASA classification and sepsis, pneumonia, mortality, or any endpoint remained significant after adjusting for sex, age, and suPAR level.

Forest plot showing most frequently occurring postoperative complications. Odds ratios (95% CI) for a univariate analyses and b multivariate analyses adjusted for sex, age, and suPAR level (above or below 5.5 ng/ml) or ASA classification (ASA I/II and III or above), with the dotted line as reference

Cox regression analysis of 90-day postoperative mortality using continuous log2-transformed suPAR levels resulted in a univariate HR of 4.5 (95% CI 3.2–6.4), and suPAR remained an independent predictor of 90-day mortality with a HR of 2.5 (95% CI 1.6–4.0) after adjusting for sex, age, and ASA classification.

Sensitivity analyses of Cox models regarding mortality

Postoperative mortality within 90 days in individual ASA groups was: ASA I: no deaths; ASA II: six deaths (3.4%); ASA III+: 25 deaths (29.3%). In a Cox model for 90 days postoperative mortality, HRs for log2-transformed suPAR in individual ASA groups were 4.4 (95% CI 1.1–18.5) for ASA II and 2.9 (95% CI 1.3–6.1) for ASA III+ after adjusting for age, sex, and log10-transformed CRP.

Time from admission to surgery was median 1 day (IQR 0–3 days). When controlling for time to surgery, in addition to sex, age, and ASA, log2-transformed suPAR remained an independent predictor for 90 days postoperative mortality with a HR of 2.6 (95% CI 1.6–4.0).

Association between ASA classification and suPAR level

We investigated the agreement between low and high ASA classification with low and high suPAR level and the categorization of postoperative mortality and obtained a Kappa interrater agreement of 0.38, defined as fair [28] (Fig. 3). The median suPAR levels increased with higher ASA classification: ASA I: 3.5 ng/ml (3.0–4.5); ASA II: 4.6 ng/ml (3.7–6.0); ASA III+: 6.2 ng/ml (4.8–8.9) P < 0.0001. No patients died (0%) in the category ASAlow/suPARlow (n = 250); four patients (9.3%) died in the category ASAhigh/suPARlow (n = 39); six patients (8.5%) died in the category ASAlow/suPARhigh (n = 65); and 21 patients (28.4%) died in the category ASAhigh/suPARhigh (n = 53); P < 0.0001 (Fig. 3).

Association between suPAR and CRP

suPAR and CRP were positively correlated (Kendall’s tau-b r = 0.10, P = 0.0046) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The median (IQR) CRP level increased in higher ASA categories: ASA I: 9.1 mg/L (2.9–38.3); ASA II: 9.7 mg/L (2.9–34.0); and ASA III+: 20.0 mg/L (4.2–85.0). CRP levels were also predictive of 90 days postoperative mortality with a HR of 2.8 (95% CI 1.6–5.0); however, this association became insignificant when adjusted for age, sex, ASA and log2-suPAR, HR 1.7 (95% CI 0.9–3.1).

In comparison, suPAR remained predictive of 90 days postoperative mortality HR 3.4 (95% CI 1.7–6.8) when adjusted for age, sex, ASA, and CRP.

CRP was also predictive of mortality (Supplementary Fig. 2) and complications in ROC analyses (Table 3); however in all patients, suPAR was significantly better at predicting mortality and all complications (P = 0.0036 and P = 0.0041, respectively).

Predictive capabilities of ASA classification, suPAR Level, and ASA classification and suPAR level combined

To evaluate the predictive capabilities for all complications across different specialties, ROC curve analyses were performed for ASA classification, suPAR level, or the combination of ASA classification and suPAR level (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for suPAR level, ASA classification, and suPAR level and ASA classification combined for prediction of any endpoint according to surgical specialties or all patients. AUCs (95% CI): general surgery: suPAR 0.68 (0.58–0.77), ASA 0.68 (0.60–0.77), combined 0.70 (0.62–0.80). Orthopedic surgery: suPAR 0.71 (0.63–0.78), ASA 0.71 (0.64–0.78), combined 0.75 (0.68–0.82). Other: suPAR 0.65 (0.51–0.78), ASA 0.68 (0.55–0.80), combined 0.71 (0.58–0.84). All patients: suPAR 0.70 (0.65–0.75), ASA 0.71 (0.66–0.76), combined 0.74 (0.69–0.79) (P values: combined vs. ASA 0.002. Combined vs. suPAR 0.009)

The suPAR level and ASA classification had approximately the same predictive value for all endpoints across all specialties. Combining the ASA classification and the suPAR level increased the AUCs (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The combined model was significantly better than using suPAR or ASA individually for all surgical patients to 0.74 (95% CI 0.69–0.79) (P: combined vs. ASA: 0.002, combined vs. suPAR: 0.009)

For suPAR levels, ROC curves predicting 90 days mortality showed an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.82–0.92) for all surgical patients, compared with ASA and CRP which had AUCs of 0.83 (95% CI 0.77–0.88) and 0.70 (95% CI 0.60–0.80), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2, Table 3).

Discussion

In this sub-study of surgical patients admitted during the TRIAGE study, we aimed to evaluate the blood level of the biomarker suPAR in the prediction of postoperative complications. We found that suPAR was significantly associated with the occurrence of postoperative complications. suPAR was equally as good as the ASA classification in predicting endpoints in all surgical patients, and better at predicting mortality and all complications compared to CRP. Adding suPAR to the ASA classification significantly improved prediction of all endpoints compared with ASA classification alone.

Globally, the ASA classification is commonly used for risk stratifying surgical patients [29]. The ASA classification has been criticized for its subjectivity, inter-observer variability, and inconsistency in classifying patients prior to surgery [30,31,32,33]. Particularly, the classification of ASA class II and III is characterized by a considerable disagreement between physicians [30]. Various preoperative risk assessment models have been developed to improve identification of patients at high risk of morbidity and mortality [27, 33,34,35]. These risk models also have limitations; for example the Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) score require intra- and postoperative information and has inaccurate estimates of mortality risk [36]; the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) requires consideration of numerous variables, making it is difficult to apply in the acute setting [37]. Therefore, these models are not commonly used in the preoperative risk assessment, because they are complicated, time-consuming, and multivariate in nature. Other simpler models add predictive value to the ASA classification; for example, the Surgical Mortality Probability Model and a similar model proposed by Glance and Donati [4, 6]. But a common feature is that risk assessment models are poorly supported by biochemical analyses.

There are numerous advantages in identifying a functional, simple, biochemically assisted, bedside model for preoperative risk scoring of surgical patients. It could enable identification of patients who will need a higher level of pre-, intra-, and postoperative care, and this may decrease the rate of postoperative mortality and morbidity. suPAR could potentially play a role in the development of an accurate, affordable, and clinically sufficient preoperative bedside model.

CRP is often used postoperatively to provide early detection of surgical infections, anastomotic leakage, and other postoperative events, and CRP is affected by surgical trauma [38,39,40].

suPAR is a stable biomarker of low-grade inflammation, associated with development and presence of various diseases, and has shown to provide prognostic value as a biomarker in acute medical patients [14, 15, 17, 20, 21]. It has been shown that the predictive value of suPAR is present years before the development of disease, and suPAR is stable during an early inflammatory state and surgical trauma [41, 42]. These properties could benefit the preoperative risk assessment by reflecting the overall inflammatory state of the patient, independent of the underlying pathologies or reasons for surgery.

The 3rd suPAR tertile had the highest mortality rate, accounting for 87% of all deaths in the cohort and more than doubled the amount of overall endpoints compared with the 1st and 2nd tertiles combined, and patients in either ASAhigh or suPARhigh groups had higher mortality rates, compared to patients in ASAlow and suPARlow groups.

Comparing the predictive capabilities of suPAR, ASA, or CRP alone and in unity shows that suPAR has an overall better prediction of complications and mortality than CRP and ASA in all specialties combined, general-, and orthopedic surgery. When adjusting for age, sex, ASA and CRP, suPAR’s HR was largely unaffected compared to CRP which was greatly weakened. This could indicate the difference in predictive capabilities between an acute phase reactant and a more stable unspecific biomarker.

As various lifestyle changes, pharmacological- and surgical treatment have been shown to result in lower suPAR levels [20, 43], it is possible that interventions leading to a reduction in a patient’s suPAR level prior to surgery could potentially lower the risk of postoperative complications.

Limitations

This is a retrospective, single-center, medical record- and registry-based sub-study to the TRIAGE study and is therefore dependent on the thoroughness in the registration of complications. Some complications may not have been registered, masked by more severe complications, or remained unnoticed. Lack of registration would underestimate the number of complications and therefore have an impact on the ability to predict those events.

We only had access to the results of the blood samples drawn at admission, and all included patients underwent surgery within 90 days of admission. In future prospective studies, blood samples drawn prior to, during surgery and samples postoperatively should be investigated, to clarify whether suPAR levels change during surgery, or if changes in suPAR levels could add predictive value postoperatively.

In our study, a small number of patients were classified as ASA III (25%), IV (1%) or ASA V (<1%). To compare suPAR levels and ASA classification, we stratified patients in high/low groups. As a result, some of the discriminatory capabilities of suPAR might be lost. Therefore, in future studies, it could be beneficial to include more patients with ASA classifications III, IV and V and examine the impact of continuous suPAR levels.

This study was designed and executed at the Department of Cardiology, Herlev hospital, parallel to studies investigating suPAR’s predictive capabilities in medical patients. Surgeons were consulted, but the expertise of surgical departments and staff should be included in the design and execution of future prospective studies on this topic.

This study does not consider the experience of the operating surgeon, or whether surgery was acute or not. In addition, the time interval between admission, subsequent suPAR measurement, and the surgical intervention varied among patients. These factors could be standardized in a future study.

Lastly, we only compared suPAR to the ASA classification. Additional studies are needed to determine whether suPAR could be a part of a smaller risk model in competition with or add predictive value to other risk scores, such as POSSUM, ACS-NSQIP, etc.

Conclusion

suPAR levels can independently predict postoperative complications and mortality. suPAR can significantly improve the predictive capabilities of the preoperative risk assessment of surgical patients performed with the ASA classification. Specifically, regarding mortality, suPAR levels add a potentially valuable predictive addition. However, an interventional study is needed to determine whether preoperative risk assessment with the addition of suPAR can reduce postoperative complications and mortality.

References

de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA (2008) The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 17(3):216–223

Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, de Keizer B, Merten H, Groenewegen PP, van der Wal G et al (2011) The incidence, root-causes, and outcomes of adverse events in surgical units: implication for potential prevention strategies. Patient Saf Surg 5:13

Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE (1961) The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA 178:261–266

Glance LG, Lustik SJ, Hannan EL, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Qian F et al (2012) The Surgical Mortality Probability Model: derivation and validation of a simple risk prediction rule for noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 255(4):696–702

Davenport DL, Bowe EA, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Mentzer RM Jr (2006) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) risk factors can be used to validate American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification (ASA PS) levels. Ann Surg 243(5):636–641 (discussion 41-4)

Donati A, Ruzzi M, Adrario E, Pelaia P, Coluzzi F, Gabbanelli V et al (2004) A new and feasible model for predicting operative risk. Br J Anaesth 93(3):393–399

Hall JC, Hall JL (1996) ASA status and age predict adverse events after abdominal surgery. J Qual Clin Pract 16(2):103–108

Rix TE, Bates T (2007) Pre-operative risk scores for the prediction of outcome in elderly people who require emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg 2:16

Cullen DJ, Apolone G, Greenfield S, Guadagnoli E, Cleary P (1994) ASA Physical Status and age predict morbidity after three surgical procedures. Ann Surg 220(1):3–9

Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL Jr (1978) ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology 49(4):239–243

Sankar A, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN (2015) How can we identify the high-risk patient? Curr Opin Crit Care 21(4):328–335

Kavsak PA, Walsh M, Srinathan S, Thorlacius L, Buse GL, Botto F et al (2011) High sensitivity troponin T concentrations in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. Clin Biochem 44(12):1021–1024

Lurati Buse GA, Koller MT, Burkhart C, Seeberger MD, Filipovic M (2011) The predictive value of preoperative natriuretic peptide concentrations in adults undergoing surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 112(5):1019–1033

Svendsen MN, Ytting H, Brunner N, Nielsen HJ, Christensen IJ (2006) Preoperative concentrations of suPAR and MBL proteins are associated with the development of pneumonia after elective surgery for colorectal cancer. Surg Infect 7(5):463–471

Galliera E, Drago L, Marazzi MG, Romano C, Vassena C, Corsi Romanelli MM (2015) Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) as new biomarker of the prosthetic joint infection: correlation with inflammatory cytokines. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 441:23–28

Eugen-Olsen J (2011) suPAR—a future risk marker. J Intern Med 270(1):29–31

Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen O, Linneberg A, Ladelund S, Hansen TW, Langkilde A et al (2010) Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. J Intern Med 268(3):296–308

Haupt TH, Petersen J, Ellekilde G, Klausen HH, Thorball CW, Eugen-Olsen J et al (2012) Plasma suPAR levels are associated with mortality, admission time, and Charlson Comorbidity Index in the acutely admitted medical patient: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 16(4):R130

Khater WS, Salah-Eldeen NN, Khater MS, Saleh AN (2016) Role of suPAR and lactic acid in diagnosing sepsis and predicting mortality in elderly patients. Eur J Microbiol Immunol 6(3):178–185

Rasmussen LJH, Ladelund S, Haupt TH, Ellekilde G, Poulsen JH, Iversen K et al (2016) Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in acute care: a strong marker of disease presence and severity, readmission and mortality. A retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med J 33:769–775

Hayek SS, Sever S, Ko YA, Trachtman H, Awad M, Wadhwani S et al (2015) Soluble urokinase receptor and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 373(20):1916–1925

Plesner LL, Iversen AK, Langkjaer S, Nielsen TL, Ostervig R, Warming PE et al (2015) The formation and design of the TRIAGE study—baseline data on 6005 consecutive patients admitted to hospital from the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 23:106

Stoelting RKMR (1994) Preoperative evaluation and the choice of anesthetic techniques. Basics of anesthesia, vol 108. Churchill Livingstone, New York

Saklad MDM (1941) Grading of patients for surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2(3):281–284

Meguid RA, Bronsert MR, Juarez-Colunga E, Hammermeister KE, Henderson WG (2016) Surgical risk preoperative assessment system (SURPAS): I. Parsimonious, clinically meaningful groups of postoperative complications by factor analysis. Ann Surg. 263(6):1042–1048

Meguid RA, Bronsert MR, Juarez-Colunga E, Hammermeister KE, Henderson WG (2016) Surgical risk preoperative assessment system (SURPAS): II. Parsimonious risk models for postoperative adverse outcomes addressing need for laboratory variables and surgeon specialty-specific models. Ann Surg 264(1):10–22

Meguid RA, Bronsert MR, Juarez-Colunga E, Hammermeister KE, Henderson WG (2016) Surgical risk preoperative assessment system (SURPAS): III. Accurate preoperative prediction of 8 adverse outcomes using 8 predictor variables. Ann Surg 264(1):23–31

McHugh ML (2012) Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 22(3):276–282

Arvidsson S, Ouchterlony J, Sjostedt L, Svardsudd K (1996) Predicting postoperative adverse events. Clinical efficiency of four general classification systems. The project perioperative risk. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 40(7):783–791

Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, Marret E, Albaladejo P, Fortier LP, Fabbro-Perray P, Malinovsky JM, Ripart J (2011) American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status system: a multicentre Francophone study to analyse reasons for classification disagreement. Eur J Anaesthesiol 28(10):742–747

Sidi A, Lobato EB, Cohen JA (2000) The American Society of anesthesiologists’ physical status: category V revisited. J Clin Anesth 12(4):328–334

Haynes SR, Lawler PGP (1995) An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation. Anaesthesia 50(3):195–199

Mak PH, Campbell RC, Irwin MG (2002) The ASA Physical Status Classification: inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anaesth Intensive Care 30(5):633–640

Knaus WA, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Lawrence DE (1981) APACHE-acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Crit Care Med 9(8):591–597

Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M (1991) POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg 78(3):355–360

Barnett S, Moonesinghe SR (2011) Clinical risk scores to guide perioperative management. Postgrad Med J 87(1030):535–541

Shah N, Hamilton M (2013) Clinical review: Can we predict which patients are at risk of complications following surgery? Crit Care 17(3):226

Platt JJ, Ramanathan ML, Crosbie RA, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Horgan PG et al (2012) C-reactive protein as a predictor of postoperative infective complications after curative resection in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 19(13):4168–4177

Singh PP, Zeng IS, Srinivasa S, Lemanu DP, Connolly AB, Hill AG (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 101(4):339–346

Straatman J, Cuesta MA, Tuynman JB, Veenhof A, Bemelman WA, van der Peet DL (2018) C-reactive protein in predicting major postoperative complications are there differences in open and minimally invasive colorectal surgery? Substudy from a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc 32(6):2877–2885

Langkilde A, Hansen TW, Ladelund S, Linneberg A, Andersen O, Haugaard SB et al (2011) Increased plasma soluble uPAR level is a risk marker of respiratory cancer in initially cancer-free individuals. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20(4):609–618

Tognoli E, Leoni M, Morelli D, Sottotetti E, Martinetti A, Signoroni S et al (2016) Serum Soluble Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator Receptor as a serum marker of inflammatory response that lead to tissue damage and surgical complication. Wound Repair Regen 24:1036–1040

Eugen-Olsen J, Ladelund S, Sorensen LT (2016) Plasma suPAR is lowered by smoking cessation: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Clin Investig 46(4):305–311

Acknowledgements

Data were provided by Danish Anesthesia Database. Travel funding was provided by ViroGates A/S, Denmark. LJHR has been supported by a Ph.D. scholarship from the Lundbeck Foundation (Grant No. R180-2014-3360).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MA, JM, MS, and LJHR have received funding for travel from ViroGates A/S, Denmark, the company that produces the suPARnostic assays. MS has received a project grant from ViroGates A/S outside the submitted work. JE-O is named inventor on patents on suPAR and prognosis. The patents are owned by Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Denmark, and licensed to ViroGates A/S. JE-O is a co-founder, shareholder and CSO of ViroGates A/S.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alstrup, M., Meyer, J., Schultz, M. et al. Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (suPAR) as an Added Predictor to Existing Preoperative Risk Assessments. World J Surg 43, 780–790 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4841-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4841-1