Abstract

Background

Suitability is a patient-centered metric defined as how appropriately health information is targeted to specific populations to increase knowledge. However, suitability is most commonly evaluated exclusively by healthcare professionals without collaboration from intended audiences. Suitability (as rated by intended audiences), accuracy and readability have not been evaluated on websites discussing pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Ten healthy volunteers evaluated fifty pancreatic cancer websites using the suitability assessment of materials (SAM instrument) for the materials’ overall suitability. Readability and accuracy were correlated.

Results

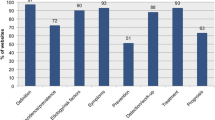

Ten recruited volunteers (ages 23–63, 50% female) found websites to be on average “adequate” or “superior” in suitability. Surgery, radiotherapy and nonprofit websites had higher suitability scores as compared to counterparts (p ≤ 0.03). There was no correlation between readability and accuracy levels and suitability scores (p ≥ 0.3). Presence of visual aids was associated with better suitability scores after controlling for website quality (p ≤ 0.01).

Conclusion

Suitability of websites discussing pancreatic cancer treatments as rated by lay audiences differed based on therapy type and website affiliation, and was independent of readability level and accuracy of information. Nonprofit affiliation websites focusing on surgery or radiotherapy were most suitable. Online information should be assessed for suitability by target populations, in addition to readability level and accuracy, to ensure information reaches the intended audience.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:7–30

Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY et al (2007) National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 246:173–180

Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS et al (2011) Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg 253:779–785

Bass SB, Ruzek SB, Gordon TF et al (2006) Relationship of Internet health information use with patient behavior and self-efficacy: experiences of newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun 11:219–236

Tian C, Champlin S, Mackert M et al (2014) Readability, suitability, and health content assessment of web-based patient education materials on colorectal cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc 80:284–290

Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C (2006) The health literacy of america’s adults: results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy (NCES 2006–483). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education, Washington, DC

Cutilli CC (2009) Bennett IM Understanding the health literacy of America: results of the national assessment of adult literacy. Orthopedic Nursing 28:27–32

Storino A, Castillo-Angeles M, Watkins AA et al (2016) Assessing the accuracy and readability of online health information for patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg 151:831–837

Eysenbach G (2003) The impact of the internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin 53:356–371

Risoldi Cochrane Z, Gregory P, Wilson A (2012) Readability of consumer health information on the internet: a comparison of U.S. government-funded and commercially funded websites. J Health Commun 17:1003–1010

Bass PF 3rd, Wilson JF, Griffith CH (2003) A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med 18:1036–1038

Mumford ME (1997) A descriptive study of the readability of patient information leaflets designed by nurses. J Adv Nurs 26:985–991

Patel SK, Gordon EJ, Wong CA et al (2015) Readability content, and quality assessment of web-based patient education materials addressing neuraxial labor analgesia. Anesth Analg 121:1295–1300

WHOis.net Lookup. WHO is.net website. https://www.whois.net/. Accessed 12 June

Weintraub D, Maliski SL, Fink A et al (2004) Suitability of prostate cancer education materials: applying a standardized assessment tool to currently available materials. Patient Educ Couns 55:275–280

Finnie RKC, Felder TM, Linder SK et al (2010) Beyond Reading Level: a systematic review of the suitability of cancer education print and web-based materials. J Cancer Educ 25:497–505

Doak CCDL, Root JH (1996) Teaching patients with low literacy skills, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, Lippincott

Hibbard JH, Peters E, Dixon A et al (2007) Consumer competencies and the use of comparative quality information: it isn’t just about literacy. Med Care Res Rev 64:379–394

Manfredi C, Czaja R, Price J et al (1993) Cancer patients’ search for information. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 14:93–104

S F Health topics: 80% of internet users look for health information online. Pew Internet & American Life Project Web site

Kaphingst KA, Zanfini CJ, Emmons KM (2006) Accessibility of web sites containing colorectal cancer information to adults with limited literacy (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17:147–151

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP Health Literacy Online: a guide to simplifying the user experience 2015

Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG et al (2006) The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns 61:173–190

Diamond A (2013) Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64:135–168

Baker DW, DeWalt DA, Schillinger D et al (2011) “Teach to goal”: theory and design principles of an intervention to improve heart failure self-management skills of patients with low health literacy. J Health Commun 16(Suppl 3):73–88

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Alliance of Families Fighting Pancreatic Cancer and the Griffith Family Foundation.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Comparisons among SAM tool sections by treatment modality are found in Table 5.

In terms of Content, surgery websites received better scores than alternative therapies (p = 0.002), chemotherapy (p = 0.003) and clinical trials (p ≤ 0.0001). Radiotherapy were scored more favorably than clinical trial websites (p = 0.002).

Regarding Literacy demand, surgery websites received better scores than alternative therapies (p = 0.001), chemotherapy (p = 0.006) and clinical trials (p ≤ 0.0001). Radiotherapy websites were superior to clinical trial websites (p = 0.0006).

Alternative therapies websites were perceived as having poorer layout than chemotherapy (p = 0.001), radiotherapy (p ≤ 0.0001) and surgery (p ≤ 0.0001). Clinical trial websites were inferior to surgery (p = 0.0018).

In Graphics, surgery websites were superior to alternative therapies (p ≤ 0.0001), chemotherapy (p = 0.031) and clinical trials (p = 0.0002). Radiotherapy websites were superior to alternative therapies (p = 0.04).

Surgery websites were superior to all other treatment modalities (p ≤ 0.0001) except radiotherapy in terms of learning stimulation. Clinical trial websites were also inferior to radiotherapy websites (p = 0.009).

In terms of cultural appropriateness, surgery websites were superior to alternative therapies (p = 0.013) and clinical trials (p = 0.022). Radiotherapy websites were also perceived as superior to alternative therapies (p = 0.04).

Comparisons among SAM tool sections by website affiliation are found in Table 6.

In content, layout and cultural appropriateness, no differences were found between affiliations (p > 0.05). In Literacy demand, nonprofit and privately owned websites received better scores than media (p = 0.045 and p = 0.015, respectively). In graphics, nonprofit and academic were perceived as superior to media websites (p = 0.03 and p = 0.02, respectively). Moreover, in learning stimulation, nonprofit (p = 0.007) and privately owned websites (p = 0.013) were superior to media.

Glossary

- Accuracy

-

The degree of concordance of the information provided with the best available evidence as evaluated by an expert panel. Scored as follows [8]: “1” for ≤ 25% of information was accurate, “2” for 26–50% of information was accurate, “3” for 51–75% of information was accurate, “4” for 76–99% of information was accurate and “5” for 100% of information was accurate.

- Health literacy

-

The ability to read, understand and act on healthcare information includes the ability to comprehend prescription labels, insurance forms and other health-related information.

- Patient education material (PEM)

-

Information presented with the intended goal of educating patients.

- Readability

-

The number of years of education required to comprehend written information computed using five standardized tests: Coleman–Liau index, Flesch–Kincaid grade level, Gunning fog index, Gobbledygook readability formula and automated readability index.

- Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine, revised (REALM-R)

-

An 8-item instrument designed to rapidly screen patients for potential health literacy problems. Patients scoring 6 or less are considered at risk of low health literacy.

- Suitability

-

The appropriateness of educational materials to the need of the intended audience. In other words, how likely patients are to choose, read, understand and act on the information provided.

- Suitability assessment of materials (SAM)

-

Standardized measure of suitability that considers six sections: content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and type, learning stimulation and motivation, and cultural appropriateness. SAM score is a percentage obtained by dividing the sum of ratings by total possible score. Websites scoring 0–39% were not suitable; 40–69% were adequate; and 70–100% were superior.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Storino, A., Guetter, C., Castillo-Angeles, M. et al. What Patients Look for When Browsing Online for Pancreatic Cancer: The Bait Behind the Byte. World J Surg 42, 4097–4106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4719-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4719-2