Abstract

Introduction

Severe acute pancreatitis may be complicated by intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH), abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS), and intestinal ischemia. The aim of this retrospective study is to describe the incidence, treatment, and outcome of patients with severe acute pancreatitis and ACS, in particular the occurrence of intestinal ischemia.

Methods

The medical records of all patients admitted with severe acute pancreatitis admitted to the ICU of a tertiary referral center were reviewed. The criteria proposed by the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS) were used to determine whether patients had IAH or ACS.

Results

Fifty-nine patients with severe acute pancreatitis were identified. Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) measurements were performed in 29 patients (49.2 %). IAH was present in all patients (29/29). ACS developed in 13/29 (44.8 %) patients. Ten patients with ACS underwent decompressive laparotomy. A large proportion of patients with ACS had intra-abdominal ischemia upon laparotomy: 8/13 (61.5 %). Mortality was high in both the ACS group and the IAH group.

Conclusion

This study confirms that ACS is common in severe acute pancreatitis. Intra-abdominal ischemia occurs in a large proportion of patients with ACS. Swift surgical intervention may be indicated when conservative measures fail in patients with ACS. National and international guidelines need to be updated so that routine IAP measurements become standard of care for patients with severe acute pancreatitis in the ICU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a well-established risk factor for intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) [1]. The incidence of IAH in patients with severe acute pancreatitis is approximately 60 % [2, 3], while ACS may occur in approximately 30 % [2]. The mortality of patients with severe acute pancreatitis who develop ACS is high at 50–75 % [2–4].

Respiratory, renal, and cardiovascular organ failures have been reported in patients with ACS. Furthermore, ACS may cause mesenteric hypoperfusion and subsequent ischemia of intra-abdominal organs [5]. Mesenteric ischemia and necrosis may also develop in severe acute pancreatitis [6]. Ischemia–reperfusion injury due in IAH and ACS has mainly been studied in animal models [7–9]. In a retrospective series in 26 children with ACS, 19 % required bowel resection due to ischemic necrosis [10]. Furthermore, raised IAP may be an important mechanism behind colonic hypoperfusion after ruptured aortic aneurysm repair [11]. However, there has not yet been a series detailing the occurrence of mesenteric ischemia in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and ACS.

The aim of this study is to describe the incidence, treatment, and outcome of patients with severe acute pancreatitis and ACS in the intensive care unit (ICU), in particular the occurrence of intestinal ischemia.

Materials and methods

Definitions

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP)

Acute pancreatitis with persistent organ failure (>48 h) as defined by the revised Atlanta criteria [12].

Multiple organ failure (MOF)

The failure of >1 organ system (respiratory, renal, or cardiovascular) [12].

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH)

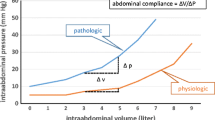

A sustained or repeated pathological elevation in IAP of 12 mmHg or higher [1] categorized into grade I (IAP 12–15 mmHg), grade II (16–20 mmHg), grade III (21–25 mmHg), and grade IV (>25 mmHg).

Abdominal compartment Syndrome (ACS)

A sustained IAP >20 mmHg that is associated with new organ dysfunction/failure, as defined by the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS) [1].

Patients

This study was conducted at a tertiary referral center for patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Patients were included who met the following criteria: (1) who were admitted to the ICU between January 2005 and May 2011 and (2) who met the revised Atlanta criteria for severe acute pancreatitis.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) age under 18 years; (2) history of chronic pancreatitis; (3) admission after resuscitation for cardiac arrest; and (4) pancreatitis was diagnosed post-mortem. Furthermore, one patient was excluded because the medical records were incomplete. Medical records of all patients were examined; this included examination of the daily nursing charts where intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) measurements are noted, the admission notes and ICU discharge notes, the discharge notes of the general ward, all surgery reports, and all microbiologic culture reports.

Transvesical IAP measurement was performed according to a standard protocol based on the WSACS consensus definitions [1].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. Dichotomous data were presented by proportions and continuous data by means (with standard deviations) or medians (with rages) according to normality. Pearson’s χ 2 test, paired and independent Student T tests, and Mann–Whitney tests were used as appropriate. Due to small numbers of events, multivariate analysis was deemed inappropriate.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifty-nine patients were identified that met the inclusion criteria. Most patients were males, around 60 years old and referred from a regional hospital. The mean interval between admission to a (regional) hospital and the tertiary ICU was 13.4 days (SD 20.7, range 0–123). The most common etiology was gallstones (40.7 %), followed by alcoholic pancreatitis (22.0 %). Most patients were critically ill; 84.7 % had MOF and 62.7 % had infected pancreatic necrosis at some point during their illness.

Intra-abdominal pressure

Patient characteristics and IAP measurements are summarized in Table 1. IAP measurement was performed in 29 out of 59 patients (49.2 %). Age and Apache II scores did not differ significantly between the group where IAP was measured, compared to where no IAP measurements were done. The mean interval between admission to a (regional) hospital and the tertiary ICU was 9.3 days in the first group and 17.2 days in the second group.

The rates of respiratory failure, shock requiring vasopressors, and renal failure were all significantly higher in the IAP group. All patients in whom IAP was measured had IAH, and 13/29 (44.8 %) met the criteria for ACS.

Patient characteristics were compared between patients who developed ACS and those who did not (Table 2). Age, gender, and APACHE II scores upon admission were comparable between the two groups. The interval between hospital admission and tertiary ICU admission was significantly shorter in the ACS group.

Treatment of ACS

Most patients with pancreatitis developed ACS within the first week of hospitalization. Three patients with ACS underwent conservative treatment (Table 3). One of these patients died within 2 days of admission to the ICU; autopsy revealed extensive ischemia of the small and large intestines. The other two patients recovered from ACS without surgery.

Decompressive laparotomy was performed in 10 patients with ACS. The mean time between hospital admittance and decompressive laparotomy was 6.5 days (SD 5.5; range 1.9–15.5 days). The range in time between diagnosis of ACS and decompressive surgery was 2–176 h, with a median of 12 h. A further two patients were reported to have undergone decompressive laparotomy but did not meet the criteria for ACS according to the WSACS. The decision to perform a decompressive laparotomy in these patients was made on clinical grounds other than IAP measurements, and they are therefore not analyzed in the ACS group. The most frequently used surgical approach was full thickness transverse subcostal laparotomy (bilateral in six cases and unilateral in one case); a midline laparotomy was performed in the other three patients. The subcostal laparotomy is a preferred approach for decompression in pancreatitis patients in this center since it provides easy access to the pancreas if necessary at a later stage. Lactate measurements were increased pre-operatively in four of seven patients with ACS and ischemia in whom decompressive surgery was performed (Table 3).

The patient with liver ischemia was managed conservatively; bowel ischemia was resected in five patients.

Effect of decompressive laparotomy

The mean IAP before surgery was 27 ± 3 mmHg, and this decreased to 18 ± 4 mmHg immediately after decompression (p = 0.001). There was an improvement in the respiratory and/or hemodynamic condition immediately after decompression in four patients (Table 3). However, four patients had a persistently high IAP >20 mmHg after decompressive surgery. In three patients, decompression had been performed using a bilateral subcostal incision and in one patient with a midline laparotomy. One patient had a relaparotomy one day after decompression with resection of ischemic cecum and left colon. Afterward, IAP decreased to 17 mmHg. One patient had a necrotic ileostomy for which partial ileum resection and a new ileostomy was placed. Two patients were managed conservatively at first but required multiple relaparotomies in the course of their disease. These patients both died from sepsis and multi-organ failure secondary to SAP. One other patient required a relaparotomy one day after decompression. This patient had been too hemodynamically unstable in the operating theater to continue the operation after decompression and was stabilized in the ICU first. This patient had necrosis of the sigmoid colon and two gastric perforations.

Intra-abdominal ischemia and outcome

Although there was significantly more shock requiring vasopressors in the group where IAP was measured (p = 0.015, Table 1), there was no significant difference in the occurrence of shock requiring vasopressors in ACS compared to the group without ACS (Table 2). Renal failure was present significantly more in patients with ACS (100 vs. 68.8 %, p = 0.048). The majority of patients in both groups developed infected pancreatic necrosis at some point during admission. Enteric fistulae and/or perforations were seen at similar rates in patients with and without ACS.

Intra-abdominal ischemia occurred in 11 of 59 patients (18.6 %). This was significantly higher in patients with ACS. In nine patients, IAP measurements had taken place; eight of these patients had ACS (Table 2). The location of ischemia varied (Table 4).

One patient died after conservative management of ACS. Autopsy revealed extensive small bowel ischemia (Table 4). The mortality in patients after decompressive surgery was 6/10 (60 %). Five of these patients (83 %) had been diagnosed with intra-abdominal ischemia upon decompressive laparotomy. Only two patients with ischemia survived until discharge from the ICU. One of these patients was subsequently discharged from the hospital and recovered fully. The other patient was transferred to another hospital and died following a neurological complication 3 months later. One patient with ACS died after supportive treatment was withdrawn after decompressive laparotomy showed extensive ischemia (Table 3). The five other patients died 28–68 days after surgery; four deaths were due to sepsis and multiple organ failure, and one death was due to bleeding complications (Table 4).

One patient with intra-abdominal ischemia had no ACS. This patient developed ischemia of the cecum one day after a laparotomy for drainage of an infected pseudocyst which was complicated by diffuse bleeding. This patient died from septic complications following multiple relaparotomies. In two patients with intra-abdominal ischemia, no IAP had been measured. One patient died from MOF within 1 day of hospitalization. Autopsy showed extensive ischemia to small intestines and colon. The other patient underwent resection of jejunum ischemia after developing acute abdominal pain one week after discharge from the ICU. This patient subsequently improved but died in hospital 1 month later due to withholding of therapy in sepsis.

Discussion

This study found that IAH and ACS are common in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, confirming earlier series [2, 3]. As a novel finding, a high incidence of intestinal ischemia was observed in patients with pancreatitis and ACS.

IAH was present in all patients in whom IAP was measured. In previous series, IAH was found in approximately 60 % of the patients studied [2, 3]. The high rate in our study may be an overestimation resulting from selective IAP measurements in patients at risk for IAH; however, it may also be a reflection of the severity of illness of patients referred to our tertiary center.

In this series, patients were admitted to a tertiary ICU after a mean interval of 13.4 days after hospitalization for the current episode of pancreatitis. In patients with ACS, this interval was a much shorter 3.8 days. Although the exact mechanisms are not completely understood, IAH in severe acute pancreatitis is usually an early phenomenon and may have an important role in the development of early organ failure [13].

Decompression laparotomy was successful in lowering the IAP in most cases. However, the mortality rate of severe acute pancreatitis with ACS was high at 54 %. This is comparable to other series [2, 3]. Mortality was even higher in the ACS group if intra-abdominal ischemia occurred (75 %).

A causal relationship between ACS and multiple organ failure in SAP is yet to be established [14]. It is likely that IAH is involved to some extent in both development of necrosis and infection of necrosis [13]. In the current study, there was no difference in infected pancreatic necrosis rates between patients who did and did not develop ACS. Mortality in SAP typically occurs in two phases: an early phase where multiple organ failure occurs with SIRS, IAH, or ACS and a later phase where mortality is due to secondary infection and necrosis [15].

The high rate of intra-abdominal ischemia observed in patients with pancreatitis and ACS has not been reported previously. Depending on its level and the overall hemodynamic condition, IAH has been associated with bowel ischaemia [16]. The small intestine may become damaged during severe acute pancreatitis, due to microcirculation disturbance associated with loss of fluids in the “third space,” hypovolemia, splanchnic vasoconstriction, and finally ischemia–reperfusion injury [17]. Intestinal damage and loss of intestinal barrier function occur early in the course of pancreatitis [18]. IAPs were not reported in this study. IAH and ACS are associated with gut barrier dysfunction as reflected by greater systemic endotoxin exposure and procalcitonin levels [19].

The association between ACS and intestinal ischemia is further described in animal studies, showing a significant decrease in perfusion of intestinal mucosa and mesenteric arterial blood flow, after IAP was increased [7, 8]. The current study suggests that IAH may be one of the mechanisms associated with intestinal damage early in the course of SAP. Further study is warranted to confirm this hypothesis.

We fully support the WSACS recommendation that protocolized monitoring of IAP should take place in high-risk patients, such as those with severe acute pancreatitis to allow early detection and treatment of IAH and ACS. The protocol in our center has been adjusted since this retrospective series to include monitoring of IAP in all high-risk patients, and we are currently enrolling patients in a prospective study to evaluate this change. Furthermore, we recommend international guidelines for treatment of pancreatitis patients be updated to include this recommendation. Three commonly used guidelines by the British Society of Gastroenterology [20], the American College of Gastroenterology [21], and the American Gastroenterological Association [22] do not yet mention the need for routine IAP measurements.

Once IAH is observed, careful monitoring of IAP and organ functions needs to take place and measures should be taken in order to prevent further organ dysfunction and irreversible damage.

Lactate monitoring seems to be of limited value in diagnosing intestinal ischemia in ACS. In this series, it was increased in only four of seven patients with ACS and intestinal ischemia. Furthermore, increased lactate levels may be a reflection of other problems than intestinal ischemia, for example, underresuscitation (Table 3). This matches conclusions from larger series: normal or decreasing lactate values by no means rule out ischemia [23, 24].

If ACS occurs, it may be managed by non-surgical interventions to lower the pressure or to prevent a further rise. These interventions may include enteral decompression with nasogastric or rectal tubes when stomach or colon are dilated, percutaneous drainage of ascites or fluid collections, prevention of overly aggressive fluid resuscitation, and neuromuscular blockade as a temporizing measure [1].

These conservative measures were not systematically employed in this group of patients, although two patients received neuromuscular blockade in an attempt to stabilize their respiratory failure in ACS. According to this institution’s protocol, patients with pancreatitis received enteral feeding via nasogastric or nasojejunal canulas. At the time, these patients were treated, the slogan in ACS was still “open the abdomen and leave it open,” compared to current opinion where conservative management, if possible, is preferred to prevent the morbidity and mortality that may result from an open abdomen.

There are no conservative measures unique to SAP patients. However, conservative measures that may especially benefit patients with SAP are prevention of overly aggressive fluid resuscitation early in the course of the disease and percutaneous drainage of ascites or other fluid collections that may complicate SAP.

There is evidence that early decompression may improve survival [13]. However, as this retrospective series confirms, mortality is still high in this group [5]. Furthermore, an open abdomen in patients with severe acute pancreatitis is associated with significant morbidity. A reasonable strategy may be to perform swift decompression in patients with multiple organ failure and ACS when conservative management fails.

It may not be feasible to conduct large multicenter randomized trials to determine optimal treatment strategies for patients with severe acute pancreatitis and ACS; however, large, prospective observational studies may be a reasonable alternative.

Limitations of this study

This study is limited by its retrospective design and small numbers. IAP measurements were conducted in a subgroup of patients. Therefore, it is unclear whether the results can be extrapolated to the entire population of patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Furthermore, many of the patients were referred to our center after having been hospitalized elsewhere with no records of IAP measurements.

Conclusion

This study confirms that IAH and ACS are common findings in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. IAH may worsen the already grim course of severe acute pancreatitis. High rates of intra-abdominal ischemia were found in patients with ACS. Early recognition of this potentially treatable aggravating condition may lead to earlier intervention and hopefully improve the outcome. We advise routine measurement of IAP in all patients with severe acute pancreatitis. National and international guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis need to be updated to include IAP measurements as standard of care and to alert clinicians to this potentially lethal complication that requires swift surgical intervention if conservative measures fail.

Key messages

-

Intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome are common in patients with severe acute pancreatitis

-

Intra-abdominal ischemia may complicate the course of pancreatitis and ACS

-

Routine measurement of IAP is advised in all patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Abdominal compartment syndrome

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- IAP:

-

Intra-abdominal pressure

- IAH:

-

Intra-abdominal hypertension

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- MOF:

-

Multiple organ failure

- SAP:

-

Severe acute pancreatitis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- VARD:

-

Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement

- WSACS:

-

World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

References

Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J et al (2013) Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med 39:1190–1206

Chen H, Li F, Sun J-B, Jia J-G (2008) Abdominal compartment syndrome in patients with severe acute pancreatitis in early stage. World J Gastroenterol 14:3541–3548

Al-Bahrani AZ, Abid GH, Holt A et al (2008) Clinical relevance of intra-abdominal hypertension in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 36:39–43. doi:10.1097/mpa.0b013e318149f5bf

Boone B, Zureikat A, Hughes SJ et al (2013) Abdominal compartment syndrome is an early, lethal complication of acute pancreatitis. Am Surg 79:601–607

van Brunschot S, Schut AJ, Bouwense SA et al (2014) Abdominal compartment syndrome in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas 43:665–674. doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000108

Mohamed SR, Siriwardena AK (2008) Understanding the colonic complications of pancreatitis. Pancreatology 8:153–158. doi:10.1159/000123607

Diebel LN, Dulchavsky SA, Brown WJ (1997) Splanchnic ischemia and bacterial translocation in the abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma 43:852–855

Cheng J, Wei Z, Liu X et al (2013) The role of intestinal mucosa injury induced by intra-abdominal hypertension in the development of abdominal compartment syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care 17:R283. doi:10.1186/cc13146

Nielsen C, Kirkegård J, Erlandsen EJ et al (2015) D-lactate is a valid biomarker of intestinal ischemia induced by abdominal compartment syndrome. J Surg Res 194:400–404. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2014.10.057

Pearson EG, Rollins MD, Vogler SA et al (2010) Decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome in children: before it is too late. J Pediatr Surg 45:1324–1329. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.107

Djavani K, Wanhainen A, Valtysson J, Björck M (2009) Colonic ischaemia and intra-abdominal hypertension following open repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 96:621–627. doi:10.1002/bjs.6592

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C et al (2013) Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 62:102–111

De Waele JJ, Leppäniemi AK (2009) Intra-abdominal hypertension in acute pancreatitis. World J Surg 33:1128–1133. doi:10.1007/s00268-009-9994-5

Trikudanathan G, Vege SS (2014) Current concepts of the role of abdominal compartment syndrome in acute pancreatitis—an opportunity or merely an epiphenomenon. Pancreatology 14:238–243. doi:10.1016/j.pan.2014.06.002

van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ et al (2010) A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 362:1491–1502. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908821

Malbrain MLNG, Chiumello D, Pelosi P et al (2004) Prevalence of intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients: a multicentre epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med 30:822–829. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2169-9

Capurso G, Zerboni G, Signoretti M et al (2012) Role of the gut barrier in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 46(Suppl):S46–51. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182652096

Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Renooij W et al (2009) Intestinal barrier dysfunction in a randomized trial of a specific probiotic composition in acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg 250:712–719. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bce5bd

Al-Bahrani AZ, Darwish A, Hamza N et al (2010) Gut barrier dysfunction in critically ill surgical patients with abdominal compartment syndrome. Pancreas 39:1064–1069. doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181da8d51

Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology, Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (2005) UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 54 Suppl 3:iii1–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057026

Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J et al (2013) American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 108:1400–1415. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218

American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute on “Management of Acute Pancreatits” Clinical Practice and Economics Committee, AGA Institute Governing Board (2007) AGA Institute medical position statement on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 132:2019–2021. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.066

Minderhout GJ, Wicke JN, de Vries BM, et al. (2011) The value of lactate measurements in detecting bowel ischemia. Intensive Care Med 37: S114–S114

Studer P, Vaucher A, Candinas D, Schnüriger B (2015) The value of serial serum lactate measurements in predicting the extent of ischemic bowel and outcome of patients suffering acute mesenteric ischemia. J Gastrointest Surg 19:751–755. doi:10.1007/s11605-015-2752-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smit, M., Buddingh, K.T., Bosma, B. et al. Abdominal Compartment Syndrome and Intra-abdominal Ischemia in Patients with Severe Acute Pancreatitis. World J Surg 40, 1454–1461 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3388-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3388-7