Abstract

Purpose

This study was designed to determine the risk of anastomotic leakage after thoracoscopic repair for esophageal atresia by digitally measuring the length of the proximal esophagus and distance of carina to proximal esophagus.

Methods

With the use of Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS), the length of the proximal esophagus from the top of the first thoracic vertebra was measured on the preoperative chest x-ray, as well as the distance from the carina to the proximal esophagus. The chest x-rays of 27 neonates, born with esophageal atresia with distal fistula, were examined. Furthermore, the tapes from the procedures were reviewed. Statistical analysis was performed with the t test for equality of means by using SPSS® 12.0.1 for Windows.

Results

Both groups were comparable, and there was a statistical significant difference in both length of the proximal esophagus (p < 0.023) and distance of carina to proximal esophagus (p < 0.022) in patients who did and did not leak postoperatively. There seems to be a tendency toward a shorter proximal esophagus in recent years that was not obvious earlier.

Conclusions

The digital measurement of the length of the proximal esophagus (M < 7 mm) and distance of carina to proximal esophagus (M > 13.5 mm) with the use of PACS gives a good risk calculation for postoperative leakage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia with distal fistula is becoming more generally accepted [1]. The outcome of these patients is critically analyzed and compared with results from open repair. In a multicenter study, Holcomb et al. (2005) described 7.6% early leakage after thoracoscopic esophageal repair and demonstrated that this was comparable with series from open repair. In a single-center series of 49 patients [2], however, a leakage of 18% was found. It is known from other series that the distance between proximal esophagus and distal fistula is of influence in the occurrence of postoperative leakage [3]. There are several methods to determine the distance, including preoperative tracheoscopy to determine the location of the distal fistula. In a more recent study, a proposal was made for evaluating the tension of the anastomosis in esophageal atresia by measuring the extent of stretching of the esophagus [4].

With the digitalization of imaging, it has become possible to exactly determine the length of the proximal esophagus and the distance from the carina to the proximal esophagus. In this study, an effort was made to explain the reason for leakage after thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia by digitally measuring the length of the proximal esophagus and distance from carina to proximal esophagus.

Patients and methods

With the availability since May 2004 of the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS), between May 2004 and June 2007, 27 neonates born with an esophageal atresia with distal fistula, who underwent thoracoscopic anastomosis, could be included in the study. Gestational age varied from 31–3/7 to 42–2/7 weeks. Birth weight was 1025 to 3690 g. Associated anomalies were encountered in 16 children (60%). The demographics are summarized in Table 1.

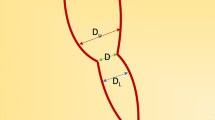

The length of the proximal esophagus was determined from the top of the first thoracic vertebra to the distal end of the Replogle® tube or the bottom of air configuration in the proximal esophagus. The distance from the carina where the left and right main stembronchus confluate in to the trachea to the tip of the Replogle® tube and/or air configuration also was measured.

Furthermore, the tapes from the procedures were reviewed and the orifice of the distal fistula was scored as aside when proximal and distal esophagus were next to each other, or above, at, or below the level of the azygos vein. Statistical analysis was performed with the t test for equality of means by using SPSS® 12.0.1. for Windows.

Results

Although there was slight difference in demographics between the two groups, there was no statistical difference (Table 1). The length of the upper pouch in the whole group varied from 3.5 to 25 mm (Fig. 1). Four patients (15%) during this period experienced postoperative leakage. The length of the upper pouch in this group varied from 3.5 to 11.9 mm (Fig. 2). In this last patient, there was an extreme subglotic stenosis, allowing only tube No. 2. During the procedure, there was an accidental extubation, which required reintubation with help of the ENT specialist using a flexible endoscope. All leakages could be managed conservatively by thoracic drainage.

The mean length in the group that experienced no postoperative leakage was 13.4 (standard deviation, 5.1) mm. The mean length in the group with leakage was 6.9 (standard deviation, 3.7) mm (p < 0.023).

The distance between carina and upper pouch was measured in both groups. The mean length in the group with no postoperative leakage was 7.9 mm, and the mean length in the leakage group was 13.6 mm (p < 0.022).

On reviewing the tapes from all procedures, there were three patients in whom the proximal and distal esophagus were “kissing.” In six patients, the distal fistula reached proximal from the azygos vein. In 14 children, the fistula was located distal from the azygos vein. In four cases, the tape could not be retrieved. In all cases in which leakage occurred, the fistula was located distal from the azygos vein. In three of four patients in this group, the proximal esophagus was short (Fig. 3).

Ten patients developed postoperative stenosis that required from one to more than ten dilatations: seven in the group (23) that experienced no postoperative leakage, and three of four patients who did have postoperative leakage. There was no difference in the number of dilatations necessary between both groups.

Discussion

As the thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia with distal fistula is becoming more popular, the outcome is scrutinized and compared to open surgery, because a new technique may be interesting, but should be of benefit to the patient. Postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage, have been described in literature to occur in 10–21% in open surgery and 7.6% in a multi-institutional analysis of thoracoscopic repair [1]. In a recent series from our department, we found postoperative leakage in 18% of 49 patients [2]. In an effort to determine the reason for this increased rate of postoperative leakage, we re-evaluated all of our patients who had undergone thoracoscopic repair of their esophageal atresia.

We had the impression that there seemed to be a tendency toward a shorter proximal esophagus, which sometimes, despite exertion of considerable pressure on the Replogle® tube, barely seemed to protrude the thoracic aperture and in a number of instances the anastomosis had to be made high up in the thorax. This was not what we were used to seeing in open surgery.

We reviewed all the chest x-rays that had been made preoperatively to see how far the Replogle® tube protruded into the thorax or how far the air configuration could be seen. With the introduction of PACS in 2004, we were able to objectively measure the length of the proximal esophagus by setting as proximal point the topside of the first thoracic vertebra and digitally measuring the distance to the lowest point of the proximal esophagus. Likewise, determining the position of the carina, we could measure the distance of the carina to the lowest point of the proximal esophagus. Thus, we could measure the length of the proximal esophagus and distance from carina to proximal esophagus in our last 27 patients in whom we encountered a leakage rate of 15%. There was a statistical significant difference in length of the proximal esophagus as well as distance between carina and proximal esophagus in the group of patients who had displayed postoperative leakage compared with the group of patients who had not leaked.

This observation could be confirmed by reviewing the tape recordings from the procedures. Apart from one patient who had an extreme subglottic stenosis with a complicated postoperative course, including leakage, all patients had a very short proximal esophagus (Fig. 3) and the distal esophagus ended well below the level of the azygos vein. There seems to be a tendency toward a shorter proximal esophagus in recent years, which was not common in the era of open esophageal atresia repair. There is no clear description in literature on the frequent occurrence of a short proximal esophagus in esophageal atresia with a distal fistula. Therefore, this observation could be the result of a changing trend in the pathogenesis of esophageal atresia with distal fistula.

The relationship of the distance between the proximal and distal esophagus and the occurrence of postoperative leakage has been subject to investigation on previous occasions [3, 4]. The digitally measurement in PACS of the length of the proximal esophagus and distance to the carina is a good predictor for risk of postoperative leakage in children with esophageal atresia and distal fistula because of the more or less fixed position of the esophagus and trachea in the thoracic cage.

Based on the means of the observations from this study, it can be concluded that patients with a length of the proximal esophagus of <7 mm and a distance from the carina to the proximal esophagus of >13.5 mm have an increased risk for postoperative leakage after primary repair of their esophageal atresia. For those centers that perform a preoperative bronchoscopy to determine the location of the fistula, digitally measurement could further substantiate the predictability of postoperative anastomotic leakage.

Another point of interest is the occurrence of postoperative stenosis requiring dilatation. Three of four patients with postoperative leakage required one to multiple dilatations for recurrent stenosis. Conversely, 7 of 23 patients who did not have postoperative leakage also needed 1 to 10 dilatations for recurrent stenosis. Recurrent stenosis seems to be more related to gastroesophageal reflux than to previous anastomotic leakage.

References

Holcomb GW 3rd, Rothenberg SS, Bax KM, et al. (2005) Thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg 242:422–428

van der Zee DC, Bax KN (2007) Thoracoscopic treatment of esophageal atresia with distal fistula and of tracheomalacia. Sem Pediatr Surg 16:224–230

McKinnon LJ, Kosloske AM (1990) Prediction and prevention of anastomotic complications of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg 25:778–781

Nagaya M, Kato J, Tanaka S, Iio K (2005) Proposal of a novel method to evaluate anastomotic tension in esophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr Surg Int 21:780–785

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Zee, D.C., Vieirra-Travassos, D., de Jong, J.R. et al. A Novel Technique for Risk Calculation of Anastomotic Leakage after Thoracoscopic Repair for Esophageal Atresia with Distal Fistula. World J Surg 32, 1396–1399 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-007-9407-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-007-9407-6