Abstract

Urban stormwater runoff has posed significant challenges in the face of urbanization and climate change, emphasizing the importance of trees in providing runoff reduction ecosystem services (RRES). However, the sustainability of RRES can be disturbed by urban landscape modification. Understanding the impact of landscape structure on RRES is crucial to manage urban landscapes effectively to sustain supply of RRES. So, this study developed a new approach that analyzes the relationship between the landscape structural pattern and the RRES in Tabriz, Iran. The provision of RRES was estimated using the i-Tree Eco model. Landscape structure-related metrics of land use and cover (LULC) were derived using FRAGSTATS to quantify the landscape structure. Stepwise regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between landscape structure metrics and the provision of RRES. The results indicated that throughout the city, the trees prevented 196854.15 m3 of runoff annually. Regression models (p ≤ 0.05) suggested that the provision of RRES could be predicted using the measures of the related circumscribing circle metric (0.889 ≤ r2 ≤ 0.954) and the shape index (r2 = 0.983) of LULC patches. The findings also revealed that the regularity or regularity of the given LULC patches’ shape could impact the patches’ functions, which, in turn, affects the provision of RRES. The landscape metrics can serve as proxies to predict the capacity of trees for potential RRES using the obtained regression models. This helps to allocate suitable LULC through optimizing landscape metrics and management guidance to sustain RRES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global unrestrained urbanization alters urban natural ecosystems and landscape structure and increases the share of impermeable surfaces in cities (Mullaney et al. 2015; Senes et al. 2021). This greatly leads to modification and disruption of the urban hydrological cycle, resulting in increased magnitude of surface water runoff and local flooding (Xu et al. 2013; Qian and Eslamian 2022). This issue is further accelerated by the extreme weather events due to global climate change in cities (Kumar et al. 2022; Muyambo et al. 2023). Consequently, not only does excessive stormwater runoff increase, but also the capability of cities to deal with these challenges diminishes (McGrane 2016; Janke et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2021). Urban stormwater can seriously affect ecosystems, built environment, people, and property (Beck et al. 2016; Subramanian 2017).

Traditional stormwater management approaches (gray infrastructure) are often inadequate and unsustainable to mitigate the current and future impacts and are also expensive to construct and maintain (US EPA 2017; Lu and Wang 2021). This has led to a demand for alternative and complementary cost-effective and sustainable approaches, primarily involving urban green infrastructure (UGI) (Wang et al. 2008; Carlyle-Moses et al. 2020; Hamel and Tan 2022). This highlights the importance of providing hydrologic ecosystem services (HES) by UGI in general and provision of runoff reduction by urban trees (RRES) in particular to mitigate stormwater issues. Urban trees facilitate HES and interact with the urban hydrologic cycle (Szota et al. 2018; Van Stan et al. 2020). The HES can decrease flow rate, peak runoff, and flooding hazards (Xiao and McPherson 2002; Kermavnar and Vilhar 2017). Previous studies have shown the positive effects of UGI, specifically urban trees, on surface runoff (Asadian and Weiler 2009; Inkiläinen et al. 2013; Li et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020).

The sustainability of HES is disturbed by urban landscape modification (Qiu and Turner 2015; Duarte et al. 2018; Metzger et al. 2021). Hydrological characteristics of a given area, including but not limited to water flow, are more influenced by landscape structure (shape or form) (Uuemaa et al. 2007). Changes in the urban spatial landscape structure alter ecological (ecosystem) functions, processes, and flow patterns (Mitchell et al. 2013; Muleta and Biru 2019). This, in turn, substantially alters the capability of urban ecosystems to provide various ecosystem services (ES), either positively or negatively (Chen et al. 2021; Yohannes et al. 2021). It is crucial to the regulating ES, particularly HES, as their supply, demand, and flow are explicitly linked to the movement and flow of the matter across urban landscapes (Eigenbrod 2016; Xia et al. 2021).

Increasing evidence, including theories (Mitchell et al. 2015a), meta-analysis (Mitchell et al. 2013; Duarte et al. 2018), conceptual frameworks (Inkoom et al. 2018), and case studies (Syrbe and Walz 2012; Kim and Park 2016; Duflot et al. 2017) has highlighted the impact of landscape structures on different ES, mainly in natural contexts. However, our understanding in this area is still in its early stages, and for many ES, how different aspects of landscape structures (most) affect their provision has not yet been well understood empirically (Lamy et al. 2016; Herrero-Jáuregui et al. 2019; Tran et al. 2022). These relations in cities are even more unclear due to the high complexity and heterogeneity (LaPoint et al. 2015; Grafius et al. 2016) and the lack of empirical studies (Dobbs et al. 2014; Grafius et al. 2018). Therefore, overcoming this critical knowledge gap in urban areas is essential.

Understanding what features of urban landscape structure affect the provision of ES, especially HES, substantially improves the landscape management knowledge and practices for sustainable ES provision (Breuste et al. 2013; Mitchell et al. 2015b). Based on the shape-function relationship, the patch’s geometrical and morphometric shape features (landscape structure) affect the landscape function regarding water flow (Amiri et al. 2019; With 2019). Landscape structural patterns are a dominant element of landscape structure (Karimi et al. 2021). It is considered a useful lever to affect the movement, flow, interaction, and provision of HES (Rieb and Bennett 2020). Although landscape structure is expected to significantly influence the provision of HES, it has not been widely studied in the urban context. Previous studies have appreciated the effects of urban landscape structure on some aspects of stormwater management through HES, including sediment erosion, flood control, peak runoff, freshwater supply, and surface and groundwater quality (Qiu and Turner 2015; Kim and Park 2016; Grafius et al. 2018; Inkoom et al. 2018; Metzger et al. 2021; Luo et al. 2022). Also, the impacts of LULC changes on runoff reduction ES have been acknowledged using landscape metrics (Zhang et al. 2015; Li et al. 2020). These studies primarily concentrated on mitigating runoff through ES provided by various LULC classes, specifically UGI, and relied on empirical models and runoff reduction coefficients from prior research to estimate the capacity of UGI to reduce runoff. However, an overlooked aspect in these studies is investigating the effects of landscape structural patterns on RRES. The existing literature highlights a gap in scientific understanding and empirical evidence concerning the relations between multiple measures of landscape structural patterns and provision of RRES, which is essential for developing ES-based landscape management tools to sustain RRES. To address this gap, this paper aims to analyze the role of urban landscape structure in the provision of RRES by analyzing the relations between landscape structural patterns and RRES in Tabriz, Iran. This city faces frequent heavy stormwater runoff and floods due to rapid urbanization, local climate and topography conditions, and global climate change, leading to severe flooding in densely inhabited areas (Mahmood Zadeh et al. 2015; Yazdani et al. 2018). Consequently, Tabriz was selected as the case study for scientific and practical purposes.

This paper seeks to empirically understand how RRES responds to the multiple measures of landscape structural pattern. The specific objectives were to (1) quantify the capacity of urban trees for runoff reduction, (2) quantify the measures of urban landscape structural pattern of LULC classes using landscape shape metrics, and (3) analyze the relations between the several measures of urban landscape structural pattern and the provision of RRES. The findings spur our understanding of how landscape structural pattern can influence the provision of RRES and help improve ES-based landscape management guidance to sustain RRES and more effectively manage stormwater runoff in cities.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

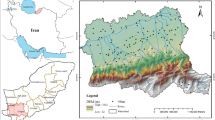

This study was conducted in Tabriz, the largest city in northwest Iran (Fig. 1). It has a population of about 1.56 million people and a 243 km² area (Statistical Center of Iran 2016). Tabriz has a mountainous topography (Asakereh and Akbarzadeh 2017), with a cold and semi-arid climate (Ghazi and Jeihouni 2022). The annual mean precipitation is 311.1 mm, with ~77.07 days experiencing rainfall of 1.0 mm or more (rainy days). The rainfall period is about 7.5 months, from 17 October to 1 June, with April having the highest average rainfall of 23 mm and August having the lowest average rainfall of 3 mm (IMO 2022). The rainfall pattern observed in Tabriz exhibits characteristics similar to that of the Mediterranean type (Jani1 et al. 2013). However, global climate change has affected the seasonal precipitation patterns, resulting in more intense rainfall events (Sanikhani et al. 2014; Sadeqi and Dinpashoh 2019). Tabriz faces a significant flood risk, with approximately 50% of its residents vulnerable to floods (Yazdani et al. 2018). The historical data showed that Tabriz had experienced about 42 cases of urban flooding from 1954 to 2009, resulting in significant human and economic losses (Soleimani-Alyar et al. 2016). Over the past century, rapid urban development and landscape changes have led to an increased share of impervious surfaces at the expense of decreasing green spaces (pervious surfaces) (Rahimi 2016).

Data Sources

The administrative map and the initial LULC map for 2020 (scale 1:25000 and minimum mapping unit of 1 m) were obtained from the municipality of Tabriz. Hourly precipitation data of the synoptic station of Tabriz for a complete calendar year was received from the Iran Meteorological Organization (IMO 2022). Other meteorological data for executing the i-Tree Eco model were automatically retrieved from the archived NOAA database (Hirabayashi and Endreny 2016). Urban tree structural data were collected through the fieldwork.

Methods

This study was carried out based on Fig. 2. The overall methodological approach of this study includes three main steps:

Assessing the Provision of RRES

To assess the provision of RRES, i-Tree tools were applied due to being one of the most appropriate, robust, fast, and process-based models to estimate RRES (Hirabayashi 2013; US EPA 2017; Nowak 2021). The i-Tree Eco model, exclusively developed for the U.S., was adapted for the study area by providing location information and hourly precipitation data to the i-Tree Database, following the protocol (i-Tree Eco International Projects 2016). The submitted data underwent a rigorous evaluation process by the U.S. Forest Service and was subsequently incorporated into the i-Tree Eco software. Subsequently, the recently appended location (Tabriz) was integrated into the subsequent versions of i-Tree Eco.

The required structural data for trees, including total height, live crown height, height to crown base, crown width, missing and health, species, tree cover, and diameter at breast height (DBH), were collected from 325 standard plots (with a radius of 11.34 m) through fieldwork during the leaf-on season following the manuals (i-Tree Eco User Manual 2016; i-Tree Field Guide 2016). Furthermore, the detailed data was collected for each plot, encompassing its precise geographical location and exact central coordinates, the proportion of the plot that was accessible and surveyed by the field crew, the percentage of the plot area covered by trees and shrubs, the quantity of space suitable for tree planting, identification of the reference objects from the plot center, the specific land use type within each plot, and the classification of ground cover types observed within each plot.

The sample size was chosen to balance data uncertainty, time constraints, limited resources, and costs for the field survey and achieve a standard error of approximately 10% for the entire city (Nowak et al. 2008). A unique methodological approach was employed to clarify the variations in RRES provision across the city. The plots were pre-stratified randomly among the LULC classes within the ten administrative districts to bring the multiple elements of RRES to each district and identify how the RRES provision varies across the districts. This approach was applied to obtain reliable observation data for further regression analysis of the relationship between landscape metrics and RRES provision (Fig. 6). Therefore, the initial LULC map was reclassified into six LULC classes (agricultural land, residential area, green infrastructure, commercial/transportation/institutional (CTI), open space and water body) according to the ten administrative districts (Fig. 3). Then the plots were pre-stratified based on LULC classes and randomly distributed among the LULC classes and urban districts using Create Random Points tool in ArcMap 10.8.2 (Fig. 1).

Based on the field data, the i-Tree Eco model estimated the structural characteristics of the urban tree population. Using the structural traits of trees (including tree species, total tree height, tree height to crown base, crown width, and missing and total tree cover) along with location information and precipitation data, the RRES was calculated using the Hydrology Effects of Trees module in i-Tree Eco for the entire city and each LULC class and district. This module estimates the various components of RRES, including rainfall interception, storage, transpiration, and evaporation, contributing to runoff reduction (Wang et al. 2008; Hirabayashi 2013; Nowak 2021). The modified Rutter methodology was utilized to simulate the process of interception (Nowak 2021). Moreover, evaporation was simulated according to the research of Deardorff (1978) and Noilhan and Planton (1989). These estimates are process-based, meaning each process is simulated separately before being linked to other processes (Hirabayashi 2013; Nowak 2021). To assess the impact of urban trees on runoff, the module assumes two scenarios: the actual (current tree conditions) and hypothetical (without trees in the same area) scenarios. For both scenarios, hourly precipitation, interception, evaporation, transpiration, and potential evapotranspiration processes are simulated first, followed by the volume of annual surface runoff. The difference in generated surface runoff between the scenarios determines the annual net RRES. Due to the effects of trees by intercepting, storing, and evaporating rainwater, the actual scenario generates less runoff than the hypothetical one. The net avoided runoff is further summarized for each tree, species, and stratum. The methods and equations are detailed in Hirabayashi (2013) and Hirabayashi and Endreny (2016).

Analyzing the Urban Landscape Structural Pattern

To analyze the urban landscape structural pattern, the metrics related to the landscape structure of LULC classes were calculated using FRAGSTATS 4.0. The equations, ranges, and a short description of each landscape metric are summarized in Table 1.

Analyzing the Relationships Between the Landscape Structural Pattern and the Provision of RRES

To model the relationship between landscape structure-related metrics and the provision of RRES, stepwise regression analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 19 software. Stepwise regression analysis is the automated computational process using forward and backward selection techniques to obtain the optimal regression (Thatcher 2021). The model omits irrelevant variables and secures that independent variables are not correlated (Johnsson 1992; Thatcher 2021). Consequently, the landscape metrics were entered into the model as independent variables, while RRES was a dependent variable. P ≤ 0.05 and P ≥ 0.100 were applied to the entry and exclusion criteria. The model outlines which landscape metrics would better explain the RRES provision. This brought about the equation to estimate the RRES:

where yi is the total annual RRES (\(m^3/yr\)) in the study area, x1…xn-1 are the landscape structure-related metrics (PARA, SHP, FRAC. RCC and CI), β1…βn-1 are the coefficients of city landscape metrics retained with P ≤ 0.05, \(\beta _0\) is a constant of the model with P ≤ 0.05 and \(\varepsilon _i\) is the error for the annual RRES.

The variation inflation factor (VIF) was also applied to assess the intervariable collinearity of the models obtained, where VIF < 10 states a lack of collinearity (Chatterjee and Hadi 2013). Scatter plots of observed versus predicted values of the total annual RRES were used to evaluate the goodness of fit for each model.

Results

Urban Tree Structure and the Corresponding RRES

The results showed that there were 1,927,566 trees (with a standard error of 12.3%), with a tree cover of 9.4% in the study area. Accordingly, they provided 8,373.04 km2 of leaf area (LA). Total LA was greatest for open spaces, followed by residential areas and GI. However, the GI, residential area and open space classes had the highest tree density, respectively (Fig. 4).

Among the administrative districts, the highest number of trees was observed in D6 (District 6), followed by D5 and D3. The total tree density was 79.33 trees ha−1, with the highest value in D10 (105 trees ha−1) (Table 2).

The results indicated that the trees reduced 196,854.15 m3 of runoff annually. Open spaces and agricultural land had the highest and lowest contribution to RRES, respectively. The majority of runoff (82%) was reduced by open spaces, residential areas, and GI at a total of 16,1425 m3 per year. This pattern is likely due to the different structural characteristics of urban trees in each LULC class (Fig. 4). GI class had the highest runoff reduction efficiency (40.51 m3ha−1yr−1), followed by residential areas, open spaces, agricultural land, and CTI (Fig. 5a).

The capacities of the different districts for runoff reduction indicated that D6 obtained the highest runoff reduction ratio (average of 28%). Districts 6, 5 and 7 were responsible for approximately half (51.1%) of total runoff reduction in the study area (Table 3). The results showed that districts’ runoff reduction efficiency (RRE) varies: D10 and D9 had the highest RRE with 10.16 and 6.92 (m3ha−1yr−1), respectively. The potential reason is that D10 and D9 have the greatest and lowest leaf area and tree number per hectare, respectively (Table 2).

Landscape Structural Pattern of LULC Classes

Descriptive statistics, including mean, maximum, minimum, standard division, and variance, were calculated for all patches (LULC classes) within districts (Table 4 and Appendix 1).

The results indicated that the LULC classes have different values of landscape structure-related metrics. The landscape metrics showed different maximum and minimum values, suggesting they all have unique insights to provide. The mean of SHP and FRAC for all patches was greater than 1, which means relative irregular, complex and convoluted patch shapes of LULC classes. All LULC patches had complex shapes because the relevant PARA values were high, indicating a deviation from the isodiametric shapes (larger edge for a given area). The CI results indicated that agricultural land had the highest patch connectedness (CI = 0.84), while the open space had the lowest patch contiguity (CI = 0.16). In total, the landscape metrics indicate that the LULC patches of the study area tended to be almost complex shapes.

The Linkage Between Landscape Structural Pattern and RRES

Multiple linear regression models were developed, explaining the RRES through landscape structure-related metrics measurements (Eqs. (2 to 7)). Other statistics for these models can be found in Table 5. The one-by-one relationships between observed and predicted RRES using landscape metrics are shown in Fig. 6.

where RRES is the annual runoff reduction provided by urban trees, RCC represents mean related circumscribing circle index for a given class of the LULC, SHP is the mean shape index for a given LULC type, R is the residential class, A is the agriculture class, CTI is the commercial/transportation/institutional class, and Ln represents natural logarithm.

The stepwise regression modeling results indicated the structural pattern’s effects on the annual RRES. The relationships between the RRES and landscape metrics were highly significant (0.889 ≤ r2 ≤ 0.983) (Table 5). The results suggested that the total RRES could be predicted using the means of the two landscape metrics: the related circumscribing circle (0.889 ≤ r2 ≤ 0.954), and the shape index (r2 = 0.983) (Table 5), indicating these indexes explain 88.9 to 98.3% of the variation of RRES across the study area. Stepwise regression modeling determined the relevance of only four LULC classes, including residential areas, CTI, agricultural land, and GI (Eqs. 2 to 7). Furthermore, PARA, FRA, and CI indexes were not observed in the developed models.

Table 5 shows that the mean RCC indices of the residential and CTI patches (Eq. 2) statistically explain 95.3 % of the overall variations in the measures of RRES. The total RRES had a negative relationship with the associated related circumscribing circle index of CTI patches (CTIRCC) (Eq. 2), showing that the lower the CTIRCC (i.e., the less narrow elongated the CTI patches are), the higher the RRES. It signifies that convoluting the shape of the CTI patches due to an increase in the RCC index would contribute to providing RRES in the city rather than elongation. Furthermore, the mean RCC for the residential area was positively correlated with the RRES. According to the RCC definition, the more narrow the elongated residential patches are, the greater the RRES in the city. This suggests that relatively narrow and elongated residential patches would play an important role in the RRES compared to relatively convoluted patches.

About 89% of the total variations in the RRES (Eqs. 3 and 4) were explained by the value of the RCC index of agricultural patches in the absence of any other metrics of LULC patches. Therefore, if the ARCC Increases in the city, the RRES will increase significantly. This indicates that the RRES is influenced by agricultural area when the patches are more narrow and elongated in the city.

About 98% of the total variations in RRES (Eqs. 6 and 7) were significantly explained by a combination of the GISHP and ASHP Hence, the shape index of GI and agricultural patches substantially affects RRES. According to the level of the model, the overall complexity of GI and agriculture patches may significantly explain the variations in RRES. Therefore, an increase in the shape index of the GI and agricultural patches (GISHP and ASHP) in the city could increase the RRES due to the higher shape irregularity of the GI and agricultural patches. Accordingly, only the modification of GI and agricultural land into square or nearly square (i.e., regularly shaped) patches would likely decrease the RRES throughout the city. The function can be deduced from the shape index of green infrastructure (GISHP) and agriculture (ASHP) patches in the city’s landscape (Eqs. 6 and 7).

Moreover, using VIF, the intervariable collinearity of the models was assessed (Table 5). All models had VIFs smaller than 1.4, indicating a lack of collinearity.

Discussion

Urban trees are recommended as an effective and complementary measure to alleviate the problem of urban stormwater runoff, improving urban sustainability (Mullaney et al. 2015; US EPA 2017; Lu and Wang 2021). To properly understand and utilize the capacity of urban trees for runoff mitigation, it is vital to obtain precise and reliable estimates of RRES. This work attempted to quantify the contributions of urban trees to runoff mitigation at the urban scale in Tabriz, Iran. The results indicated that urban trees are effective in mitigating runoff. They can reduce 196.85 × 103 m3 of stormwater runoff annually. Different runoff reduction capacities have been observed due to the various urban LULC classes. The open spaces had shown the highest runoff reduction (Fig. 4). A potential reason is that open spaces tend to have the highest share of area (45.4%) in general and more leaf area and tree number in particular.

On the other hand, as regards runoff reduction efficiency (Fig. 5, a), GI, which covers the lowest area in the city (3.1%), has the highest efficiency due to the greatest leaf area per hectare and tree density (456 tree ha−1). This is also true for urban districts; the more tree density the district has, the more RRES was observed. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that leaf area is one of the most important factors in runoff reduction process by urban trees (Nowak 2021). So, runoff reduction efficiency provides a better understanding of the potential of each LULC type and district in runoff reduction. Knowledge of the runoff reduction capacity of urban trees within LULC classes in different urban districts can contribute to proper management as local municipalities manage each district independently.

The effect of the GI and agricultural land in this study agrees with previous studies (Pace and Sales 2012; Mikulanis 2014; Nowak et al. 2017), identifying green spaces as the main source of runoff reduction. The comparison of urban tree traits and RRES across the cities (Table 6) indicates that Tabriz has a somewhat near-the-average tree number; however, the tree cover ranks among the lowest, exceeding only Phoenix, implying its trees are quite small and young. Estimated annual runoff reduction efficiency has ranged from 8.04 to 71.52 m3 per tree, within which Tabriz has the lowest value. Although tree characteristics may be the primary contributor to this low efficiency, as 78 % of the existing trees are not large enough to produce significant runoff reduction, the effects of rainfall (amount, duration, and pattern) could not be ignored on runoff reduction (Nytch et al. 2019). Despite the modest RRE in the study area, such a reduction in surface runoff can have considerable environmental benefits in addition to the significant reduction in stormwater management costs.

The usefulness of the ES concept for landscape and ecosystem management depends on our knowledge of links between landscape structure and ES provision (Mitchell et al. 2013). Since HES provision can be either directly or indirectly affected by landscape structure (Chen et al. 2021; Yohannes et al. 2021), improving our knowledge of the interactions between landscape structure and RRES provision by integrating the concepts of landscape ecology and ES into urban hydrology helps effectively manage urban landscapes and resiliently maintain and enhance the sustainability of HES supply (Mitchell et al. 2013; Francis et al. 2022; Tran et al. 2022). However, the empirical understanding of how landscape structure impacts RRES provision remains limited. This gap limits our ability to manage urban landscape effectively for RRES. To bridge this gap, this study assessed the impacts of landscape structural patterns, particularly the shape of LULC patches, on RRES provision. The findings provided direct evidence that the shape of urban LULC patches significantly influences RRES capacity. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the importance of landscape structure in providing HES (Zhang et al. 2015; Li et al. 2020).

In doing so, we emphasize how LULC patches’ shape can mediate the RRES supply. To sum up the findings, it is noteworthy that only two of the five studied landscape structure-related metrics (shape and related circumscription circle metrics) have resulted in reliable models for predicting the provision of RRES. The results indicate that SHP and RCC metrics are the influential determinants of RRES and could be applied in RRES assessment. This is consistent with those of the previous study, which analyzed the links between flooding phenomena with landscape metrics on a larger scale using the same landscape metrics (Amiri et al. 2018).

The finding showed that the RCC metric for agricultural patches could be applied to develop the RRES prediction model. However, applying the RRES prediction models, which are based on the RCC metric for residential areas and CTI, could provide more reliable estimations to their users. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the more elongated the shape of the residential and agricultural patches, the greater the supply of RRES. Therefore, expanding agricultural and residential patches may only improve the capacity of trees to mitigate runoff if they have more elongated and narrower shapes, but an extended CTI with a more convoluted shape would be advantageous. However, regularity or irregularity in the shape of the GI and agricultural patches, specifically the degree by which their patches deviate from an iso-diametric shape as reflected by differences in shape index, was observed to be significantly related to the extent of RRES. The results showed that increasing the degree of shape irregularity in the GI and agricultural patches improves their contribution to runoff mitigation.

Even though the previous works (e.g., Buckland et al. 2020; Rogers et al. 2015; Watson et al. 2017) have demonstrated that urban trees in green spaces have a considerable impact on stormwater runoff; the results of this study suggest that, in addition to current GI cover, the shape of the GI patches should also be considered.

Our approach can help to understand the RRES provisioning mechanism better and provides useful information for the urban decision support system to improve the sustainable functionality of the landscape. We have found a strong influence of the structural pattern on RRES. While some of the relationships between landscape structure and HES have been outlined in previous research (Dobbs et al. 2014; Grafius et al. 2018; Karimi et al. 2021), this work expands our understanding of the influence of landscape structural pattern on the RRES.

The results showed evidence of support for the role of landscape structure in maintaining the RRES in urbanized areas now and into the future. Understanding the impacts of the structural pattern on ES is a significant research goal that provides a foundation for alternative landscape management, planning, and restoration strategies (Turner et al. 2013). These findings can contribute to improving urban landscape planning and management with respect to sustainable urban runoff reduction. This helps to cover the necessity of carrying out ES assessment in parallel with and according to the urban landscape planning process (Grunewald and Bastian 2015).

Assessing the impacts of different urban landscape plans on multiple dimensions particularly ES, is crucial for establishing optimal landscape strategies (Termorshuizen and Opdam 2009; Francis et al. 2022). Through integrating the i-Tree Eco measurements with conventional landscape structure metrics analyses, this research provides an explicit landscape metrics-based tool to describe variations in the RRES capacity. This provides a potential approach to evaluate the response of RRES to changes in the urban landscape structural pattern. Urban decision-makers and planners can use it to establish optimal spatial policies and assess the impacts of their landscape strategies on the capacity of tree to provide RRES. In fact, once the urban land use strategies are defined, the obtained regression models could be an easy-to-use way to rapidly and iteratively assess whether the proposed strategies will result in positive or negative changes in RRES. This helps to identify how to change the landscape to improve the RRES provision and is in line with the critical elopement of landscape planning which aims to maintain the functions of the landscape and ecosystem (Grunewald and Bastian 2015).

This study helps to link ES assessment and urban landscape planning, which initially have different focuses (Grunewald and Bastian 2015). We try to bridge a gap in the field of integrating ES into landscape ecology and spatial planning, which can ease dialog with different practitioners and decision-makers. Despite the growing body of literature on ES, it has not been fully integrated into urban landscape planning and decision-making (Anna Hermann et al. 2011). Some of the main questions that need to be answered are 1) how can the relationships between ES and landscape characteristics be quantified and modeled? and 2) what is the effect of landscape features on ES? (de Groot et al. 2010). One approach to cover these challenging questions is better understanding the interrelations between LULC and ES (Verburg et al. 2009). This study tries to answer these questions and aims to integrate the ES concept into urban landscape management, planning and decision-making by analyzing the interactions between RRES and structural characteristics of LULC. Integrating landscape concepts into ES helps the ES framework to convey the complex relationships of socio-ecological systems and resolve its operational gaps (Angelstam et al. 2019).

This paper also helps to cover one of the main research directions of the "ES at the landscape scale" (Müller et al. 2010) by providing a suitable methodology to apply ES at the landscape scale and integrating ES in landscape analysis. This study contributes to the existing body of literature (Bastian 2001; Syrbe and Walz 2012; Babí Almenar et al. 2018), which advocate expanding the landscape ecology paradigm and highlighting the necessity for making an appropriate foundation for the resolution of urban planning subjects through analyzing the linkage between landscape structure and ES.

Although using the i-Tree Eco model to estimate RRES offers distinct benefits, including utilizing locally gathered field data, process-based hydrology estimations and modeling, and eco-hydrology of trees, it also has uncertainties and limitations. These drawbacks stem from simplifying (sub)surface hydrology to reflect the effects of urban trees, excluding of changing amounts of impervious cover, dismissing the impacts of the various spatial configuration of trees or other LULC types and applying default soil and hydrologic parameters (Hirabayashi 2013; Nowak 2021). Future research is required to help overcome these uncertainties and limitations.

Another limitation of this study is that it has focused on analyzing the effects of landscape structural patterns in an urban area with the varying terrain and topographic and hydrologic gradients, which might be considered to identify the impact of these variables.

To improve the knowledge of how landscape structure influences HES, future works are needed to consider additional biophysical, cultural, and social drivers at different spatial and temporal scales, as these factors determine ES distribution (Eigenbrod 2016). Further attempts are needed to study the impacts of landscape structure on multiple ES at once (ES bundles) and other dimensions of the ES delivery process. Comprehensive scenario analysis of future changes in rainfall, tree characteristics, landscape structure, LULC, and subsequently in RRES is required for long-term sustainable urban planning. Furthermore, analysis of the impacts of the other aspects of landscape, such as composition and connectivity on RRES using other landscape metrics can be considered in additional research.

Conclusions

This paper provides the empirical basis to evaluate the hypothesis that urban landscape structural pattern impacts the REES provision. First, we provided the theoretical fundaments that suggest the landscape structure would affect the supply of HES and how common research concentrates on the links between landscape structure and HES. Second, by developing a new approach, we brought empirical evidence of how urban landscape structure affects RRES, which is required to manage and model RRES provision across urban landscapes accurately.

The idea for this work was due to the absence of empirical evidence on the relationship between landscape structure and RRES. This paper provided an explicit location-based estimation tool based on landscape metrics to describe variations in the RRES.

This study revealed the significant influence of the spatial shape of landscape on RRES and showed linear responses of the RRES to landscape metrics: shape and related circumscribing circle. Specifically, consistent with the shape-function relationship principle, we argue that the landscape structural pattern will significantly mediate the provision of RRES.

Our approach made it possible to predict the effects of changes in landscape structure on providing RRES. The findings have indicated that a change in the shape of the LULC due to the alteration of the structural attributes and landscape metrics of the LULC would cause a change in the runoff reduction capacity of trees as a process.

The findings would help urban environmental managers and policymakers better understand the importance of landscape structure when thinking about improving runoff mitigation capacity and, consequently, establishing proper LULC strategies through optimizing landscape metrics that result in positive changes in the supply of RRES. The landscape structure metrics could be served as capable and cost-effective indicators to assess RRES and monitor changes in RRES provision produced by several urban plans, such as a masterplan.

This work provides practical information for urban spatial planning by incorporating ES concept and landscape ecological perspective. The results could improve urban plans by considering landscape structure in the RRES supply.

This research helps to overcome the lack of a coherent and integrated approach to ES assessment at the level of methods. The findings contributed to an evolving body of knowledge on the relationship between landscape structure and ES provision and help to incorporate landscape structure into ES framework. The findings help to pave the way for expanding the urban landscape ecology paradigm and provide an appropriate foundation for the resolution of urban planning subjects through analyzing the linkage between landscape structure and RRES.

We suggest that this work may give a flexible approach with the potential to advance the application of the ES concept in practice for sustainable urban stormwater management and help to improve current tools and approaches. As the ES concept is increasingly integrated into urban decision-making and planning processes, this research contributes to a better understanding of the provision of ES on the landscape scale.

Expanding the approach to other cities and ES can illuminate and improve the capacity to identify ecological value in terms of ES provision and emphasize ES’s essential structural factors specific to each landscape.

References

Amiri BJ, Gao J, Fohrer N, Adamowski J (2019) Regionalizing time of concentration using landscape structural patterns of catchments. J Hydrol Hydromech 67:135–142. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2018-0041

Amiri BJ, Junfeng G, Fohrer N et al. (2018) Regionalizing Flood Magnitudes using Landscape Structural Patterns of Catchments. Water Resour Manag 32:2385–2403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-018-1935-3

Angelstam P, Munoz-Rojas J, Pinto-Correia T (2019) Landscape concepts and approaches foster learning about ecosystem services. Landsc Ecol 34:1445–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00866-z

Anna H, Sabine S, Thomas W (2011) The concept of ecosystem services regarding landscape research: a review. Living Rev Landsc Res 5:1–37

Asadian Y, Weiler M (2009) A new approach in measuring rainfall interception by urban trees in coastal British Columbia. Water Qual Res J Can 44:16–25

Asakereh H, Akbarzadeh Y (2017) Simulation of temperature and precipitation changes of tabriz synoptic station using statistical downscaling and Canesm2 climate change model output. J Geogr Environ Hazards 6:153–174. https://doi.org/10.22067/GEO.V6I1.54791

Babí Almenar J, Rugani B, Geneletti D, Brewer T (2018) Integration of ecosystem services into a conceptual spatial planning framework based on a landscape ecology perspective. Landsc Ecol 33:2047–2059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0727-8

Bastian O (2001) Landscape Ecology– towards a unified discipline? Landsc Ecol 16:757–766

Beck SM, McHale MR, Hess GR (2016) Beyond impervious: urban land-cover pattern variation and implications for watershed management. Environ Manag 58:15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0700-8

Breuste J, Haase D, Elmqvist T (2013) Urban Landscapes and Ecosystem Services. In: Wratten S, Sandhu H, Cullen R, Costanza R (eds) Ecosystem Services in Agricultural and Urban Landscapes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Oxford, UK, pp 83–104

Buckland A, Sparrow K, Handley P, et al (2020) Valuing Newport’s Urban Trees. A report to Newport City Council and Welsh Government

Carlyle-Moses DE, Livesley S, Baptista MD et al. (2020) Urban Trees as Green Infrastructure for Stormwater Mitigation and Use. In: Levia DF, Carlyle-Moses DE, Iida S, et al., (eds) Forest-Water Interactions, 1st ed. Springer, Cham, p 397–432

Chatterjee S, Hadi AS (2013) Regression analysis by example, 5th Ed. JohnWiley and Sons, NewYork

Chen W, Zeng J, Chu Y, Liang J (2021) Impacts of landscape patterns on ecosystem services value: A multiscale buffer gradient analysis approach. Remote Sens 13:2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13132551

de Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L et al. (2010) Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complex 7:260–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecocom.2009.10.006

Deardorff JW (1978) Efficient prediction of ground surface temperature and moisture, with inclusion of a layer of vegetation. J Geophys Res 83:1889. https://doi.org/10.1029/jc083ic04p01889

Dobbs C, Kendal D, Nitschke CR (2014) Multiple ecosystem services and disservices of the urban forest establishing their connections with landscape structure and sociodemographics. Ecol Indic 43:44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.02.007

Duarte GT, Santos PM, Cornelissen TG et al. (2018) The effects of landscape patterns on ecosystem services: meta-analyses of landscape services. Landsc Ecol 33:1247–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0673-5

Duflot R, Ernoult A, Aviron S et al. (2017) Relative effects of landscape composition and configuration on multi-habitat gamma diversity in agricultural landscapes. Agric Ecosyst Environ 241:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.035

Eigenbrod F (2016) Redefining landscape structure for ecosystem services. Curr Landsc Ecol Rep. 1:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40823-016-0010-0

Francis RA, Millington JDA, Perry GLW, Minor ES (2022) The Routledge Handbook of Landscape Ecology. Rouledge, Oxford, UK

Ghazi B, Jeihouni E (2022) Projection of temperature and precipitation under climate change in Tabriz, Iran. Arab J Geosci 15:621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-09848-z

Grafius DR, Corstanje R, Harris JA (2018) Linking ecosystem services, urban form and green space configuration using multivariate landscape metric analysis. Landsc Ecol 33:557–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0618-z

Grafius DR, Corstanje R, Warren PH et al. (2016) The impact of land use/land cover scale on modelling urban ecosystem services. Landsc Ecol 31:1509–1522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0337-7

Grunewald K, Bastian O (2015) Ecosystem Services - Concept, Methods and Case Studies

Hamel P, Tan L (2022) Blue–green infrastructure for flood and water quality management in Southeast Asia: evidence and knowledge gaps. Environ Manag 69:699–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01467-w

Herrero-Jáuregui C, Arnaiz-Schmitz C, Herrera L et al. (2019) Aligning landscape structure with ecosystem services along an urban–rural gradient. Trade-offs and transitions towards cultural services. Landsc Ecol 34:1525–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0756-3

Hirabayashi S (2013) i-Tree Eco precipitation interception model descriptions. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; Davey Tree Expert Co.; and other cooperators, Kent, OH

Hirabayashi S, Endreny TA (2016) Surface and Upper Weather Pre processor for i Tree Eco and Hydro

i-Tree Eco International Projects (2016) Eco Guide to International Projects

i-Tree Eco User’s Manual (2016) i-Tree Eco User’s manual

i-Tree Field Guide (2016) i-Tree Eco Field Guide

IMO (2022) Historical dataset of climate and average Weather in Tabriz. Iran Meteorological organization (IMO), East Azerbaijan, Iran

Inkiläinen ENM, McHale MR, Blank GB et al. (2013) The role of the residential urban forest in regulating throughfall: A case study in Raleigh, North Carolina, USA. Landsc Urban Plan 119:91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.07.002

Inkoom JN, Frank S, Greve K, Fürst C (2018) A framework to assess landscape structural capacity to provide regulating ecosystem services in West Africa. J Environ Manag 209:393–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.027

Janil R, Ghorbani MA, Saghafian B et al. (2013) Dynamic characteristics of monthly rainfall in Tabriz under climate change. J Civ Eng Urban 25:225–235

Janke BD, Finlay JC, Hobbie SE (2017) Trees and streets as drivers of urban stormwater nutrient pollution. Environ Sci Technol 51:9569–9579. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b02225

Johnsson T (1992) A procedure for stepwise regression analysis. Stat Pap 33:21–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02925308

Karimi JD, Corstanje R, Harris JA (2021) Understanding the importance of landscape configuration on ecosystem service bundles at a high resolution in urban landscapes in the UK. Landsc Ecol 36:2007–2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01200-2

Kermavnar J, Vilhar U (2017) Canopy precipitation interception in urban forests in relation to stand structure. Urban Ecosyst 20:1373–1387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-017-0689-7

Kim HW, Park Y (2016) Urban green infrastructure and local flooding: The impact of landscape patterns on peak runoff in four Texas MSAs. Appl Geogr 77:72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2016.10.008

Kumar S, Agarwal A, Ganapathy A et al. (2022) Impact of climate change on stormwater drainage in urban areas. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 36:77–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-021-02105-x

Lamy T, Liss KN, Gonzalez A, Bennett EM (2016) Landscape structure affects the provision of multiple ecosystem services. Environ Res Lett 11:124017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/124017

LaPoint S, Balkenhol N, Hale J et al. (2015) Ecological connectivity research in urban areas. Funct Ecol 29:868–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12489

Li L, Van Eetvelde V, Cheng X, Uyttenhove P (2020) Assessing stormwater runoff reduction capacity of existing green infrastructure in the city of Ghent. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 27:749–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1739166

Liu W, Feng Q, Deo RC et al. (2020) Experimental study on the rainfall-runoff responses of typical urban surfaces and two green infrastructures using scale-based models. Environ Manag 66:683–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01339-9

Lu G, Wang L (2021) An integrated framework of green stormwater infrastructure planning—a review. Sustainability 13:13942. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413942

Luo Z, Tian J, Zeng J, Pilla F (2022) Resilient landscape pattern for reducing coastal flood susceptibility. Sci Total Environ In Press:159087. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.159087

Mahmood Zadeh H, Emami Kia V, Rasooli AA (2015) Micro zonation of flood risk in tabriz suburb with using analytical hierarchy process. Geogr Res 30:167–180

Mcgarigal K, Marks BJ (1994) FRAGSTATS: spatial pattern analysis program for quantifying landscape structure. Portland

McGrane SJ (2016) Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: a review. Hydrol Sci J 61:2295–2311. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2015.1128084

Metzger JP, Villarreal-Rosas J, Suárez-Castro AF et al. (2021) Considering landscape-level processes in ecosystem service assessments. Sci Total Environ 796:149028. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2021.149028

Mikulanis V (2014) Phoenix, Arizona Project Area, Community Forest Assessment

Mitchell MGE, Bennett EM, Gonzalez A (2013) Linking landscape connectivity and ecosystem service provision: current knowledge and research gaps. Ecosystems 16:894–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9647-2

Mitchell MGE, Bennett EM, Gonzalez A (2015a) Strong and nonlinear effects of fragmentation on ecosystem service provision at multiple scales. Environ Res Lett 10:094014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/9/094014

Mitchell MGE, Suarez-Castro AF, Martinez-Harms M et al. (2015b) Reframing landscape fragmentation’s effects on ecosystem services. Trends Ecol Evol 30:190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.01.011

Muleta TT, Biru MK (2019) Human modified landscape structure and its implication on ecosystem services at Guder watershed in Ethiopia. Environ Monit Assess 191:95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7403-6

Mullaney J, Lucke T, Trueman SJ (2015) A review of benefits and challenges in growing street trees in paved urban environments. Landsc Urban Plan 134:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.10.013

Müller F, de Groot R, Willemen L (2010) Ecosystem services at the landscape scale: The need for integrative approaches. Landsc Online 23:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3097/LO.201023

Muyambo F, Belle J, Nyam YS, Orimoloye IR (2023) Climate-change-induced weather events and implications for urban water resource management in the free state province of South Africa. Environ Manag 71:40–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-022-01726-4

Noilhan J, Planton S (1989) A simple parameterization of land surface processes for meteorological models. Mon Weather Rev 117:536–549. 10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<0536:ASPOLS>2.0.CO;2

Nowak D, Walton JT, Stevens JC et al. (2008) Effect of plot and sample size on timing and precision of urban forest assessments. Arboric Urban 34:386–390

Nowak DJ (2021) Understanding i-Tree:2021 Summary of Programs and Methods. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Statio, Madison, WI

Nowak DJ, Bodine AR, Hoehn RE, et al (2017) Houston’s Urban Forest, 2015

Nytch CJ, Meléndez-Ackerman EJ, Pérez ME, Ortiz-Zayas JR (2019) Rainfall interception by six urban trees in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Urban Ecosyst 22:103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-018-0768-4

Pace M, Sales T (2012) Mesquite Urban Forest Ecosystem Analysis

PARD P (2014) Plano Urban Forest Ecosystem Analysis

Qian Q, Eslamian S (2022) Impact of Urbanization on Flooding. In: Eslamian S, Eslamian FA (eds) Flood Handbook; Impacts and Management, 1st edn. CRC Press, Oxford, UK, p 16

Qiu J, Turner MG (2015) Importance of landscape heterogeneity in sustaining hydrologic ecosystem services in an agricultural watershed. Ecosphere 6:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00312.1

Rahimi A (2016) A methodological approach to urban landuse change modeling using infill development pattern—a case study in Tabriz, Iran. Ecol Process 5:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-016-0044-6

Rieb JT, Bennett EM (2020) Landscape structure as a mediator of ecosystem service interactions. Landsc Ecol 35:2863–2880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01117-2

Rogers K, Sacre K, Goodenough J, Doick K (2015) Valuing London’s urban forest - Results of the London i-Tree Eco project. Treeconomics, London, UK

Rutledge D (2003) Landscape indices as measures of the effects of fragmentation: can pattern reflect process? New Zealand Department of Conservation. Oxford, UK

Sadeqi A, Dinpashoh Y (2019) Projection of precipitation and its variability under the climate change conditions in the future periods (Case Study: Tabriz). Environ Water Eng 5:339–350. https://doi.org/10.22034/JEWE.2020.210941.1339

Sanikhani H, Mirabbasi Najaf Abadi R, Dinpashoh Y (2014) Modeling of temperature and rainfall of tabriz using copulas. Irrig Water Eng 5:123–133

Senes G, Ferrario PS, Cirone G et al(2021) Nature-based solutions for storm water management—creation of a green infrastructure suitability map as a tool for land-use planning at the municipal level in the province of Monza-Brianza (Italy) Sustainability 13:6124

Soleimani-Alyar M, Ghaffari-Hadigheh A, Sadeghi F (2016) Controlling floods by optimization methods. Water Resour Manag 30:4053–4062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-016-1272-3

Statistical Center of Iran (2016) Population and Housing Censuses, Censuses 2016. https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Population-and-Housing-Censuses. Accessed 28 Mar 2018

Subramanian R (2017) Rained out: Problems and solutions for managing urban stormwater runoff. Ecol Law Q 43:421–447

Syrbe RU, Walz U (2012) Spatial indicators for the assessment of ecosystem services: Providing, benefiting and connecting areas and landscape metrics. Ecol Indic 21:80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.02.013

Szota C, Thom JK, Fletcher TD et al. (2018) Street tree stormwater control measures can reduce runoff but may not benefit established trees. Landsc Urban Plan 182:144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.10.021

Termorshuizen JW, Opdam P (2009) Landscape services as a bridge between landscape ecology and sustainable development. Landsc Ecol 24:1037–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-008-9314-8

Thatcher RM (2021) Automatic Multivariate Normal Stepwise Regression Analysis. Hassell Street Press, Oxford, UK

Tran DX, Pearson D, Palmer A et al. (2022) Quantifying spatial non-stationarity in the relationship between landscape structure and the provision of ecosystem services: An example in the New Zealand hill country. Sci Total Environ 808:152126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152126

Turner MG, Donato DC, Romme WH (2013) Consequences of spatial heterogeneity for ecosystem services in changing forest landscapes: Priorities for future research. Landsc Ecol 28:1081–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9741-4

US EPA (2017) Stormwater to Street Trees: Engineering Urban Forests for Stormwater Management. Lulu

Uuemaa E, Roosaare J, Mander Ü (2007) Landscape metrics as indicators of river water quality at catchment scale. Hydrol Res 38:125–138. https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2007.002

Van Stan JT, Gutmann E, Friesen J (2020) Precipitation partitioning by vegetation: A global synthesis. Springer, Cham

Verburg PH, van de Steeg J, Veldkamp A, Willemen L (2009) From land cover change to land function dynamics: A major challenge to improve land characterization. J Environ Manag 90:1327–1335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.08.005

Wang J, Endreny TA, Nowak DJ (2008a) Mechanistic simulation of tree effects in an urban water balance model. J Am Water Resour Assoc 44:75–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2007.00139.x

Watson J, Bayley J, Sacre K, Rogers K (2017) Valuing Oldham’s urban forest

With KA (2019) Essentials of Landscape Ecology, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Xia H, Kong W, Zhou G, Sun OJ (2021) Impacts of landscape patterns on water-related ecosystem services under natural restoration in Liaohe River Reserve, China. Sci Total Environ 792:148290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148290

Xiao Q, McPherson EG (2002) Rainfall interception by Santa Monica’s municipal urban forest. Urban Ecosyst 6:291–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ueco.0000004828.05143.67

Xu C, Chen Y, Chen Y et al. (2013) Responses of surface runoff to climate change and human activities in the arid region of central asia: a case study in the Tarim River Basin, China. Environ Manag 51:926–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0018-8

Yazdani MH, Ghasemi M, Saleki Maleki MA (2018) Micro-zoning vulnerability of cities against flood risk (case study: Tabriz city). Q Sci J Rescue Reli 10:33–44

Yohannes H, Soromessa T, Argaw M, Dewan A (2021) Impact of landscape pattern changes on hydrological ecosystem services in the Beressa watershed of the Blue Nile Basin in Ethiopia. Sci Total Environ 793:148559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148559

Zhang B, Xie G, di, Li N, Wang S (2015) Effect of urban green space changes on the role of rainwater runoff reduction in Beijing, China. Landsc Urban Plan 140:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.03.014

Zhou L, Shen G, Li C et al. (2021) Impacts of land covers on stormwater runoff and urban development: A land use and parcel based regression approach. Land use policy 103:105280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105280

Author contributions

This research was funded by IDUB grant under the increased by 2% subsidy for the University of Lodz, which took part in the competition under the “The Excellence Initiative – Research University” Program for the year 2021. Conceptualization:Vahid Amini Parsa, Jakub Kronenberg, Bahman Jabbarian Amiri; Methodology: Vahid Amini Parsa, Mustafa Nur Istanbuly, Bahman Jabbarian Amiri; Software: Vahid Amini Parsa, Mustafa Nur Istanbuly; Data curation: Vahid Amini Parsa; Formal analysis and investigation: Vahid Amini Parsa, Mustafa Nur Istanbuly; Visualization: Vahid Amini Parsa; Writing - Original draft preparation: Vahid Amini Parsa; Writing - Reviewing & editing: Vahid Amini Parsa, Jakub Kronenberg, Alessio Russo, Bahman Jabbarian Amiri; Supervision: Jakub Kronenberg, Bahman Jabbarian Amiri; Validation: Jakub Kronenberg, Bahman Jabbarian Amiri

Funding

This research was funded by IDUB grant under the increased by 2% subsidy for the University of Lodz, which took part in the competition under the “The Excellence Initiative – Research University” Program for the year 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Appendix 1 The landscape structure-related metrics distribution statistics for LULC classes within each district

Appendix 1 The landscape structure-related metrics distribution statistics for LULC classes within each district

Urban districts | Landscape metrics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CRC | CI | FRAC | PARA | SHP | |||||||||||||||||||||

CTI | Agricultural land | GI | Residential area | Open space | CTI | Agricultural land | GI | Residential area | Open space | CTI | Agricultural land | GI | Residential area | Open space | CTI | Agricultural land | GI | Residential area | Open space | CTI | Agricultural land | GI | Residential area | Open space | |

D1 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.12 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 8,033.30 | 735.05 | 8,746.02 | 3,298.51 | 11,383.50 | 1.16 | 1.61 | 1.72 | 1.68 | 1.26 |

D2 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.89 | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.15 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 6,204.21 | 1,250.72 | 8,802.72 | 2,325.06 | 10,797.28 | 1.18 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 1.54 | 1.25 |

D3 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.71 | 0.15 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 7,578.55 | 1,274.98 | 4,608.95 | 3,422.23 | 10,634.94 | 1.14 | 1.63 | 1.61 | 1.75 | 1.22 |

D4 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 8,939.97 | 1,937.47 | 5,693.92 | 4,119.78 | 10,951.68 | 1.12 | 1.69 | 1.50 | 1.86 | 1.32 |

D5 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.18 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 1.12 | 1.13 | 5,008.45 | 2,359.80 | 7,489.43 | 2,863.24 | 10,619.74 | 1.27 | 1.54 | 1.65 | 1.53 | 1.48 |

D6 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 6,078.83 | 3,133.51 | 5,177.65 | 3,986.69 | 10,310.91 | 1.21 | 1.74 | 1.92 | 1.68 | 1.41 |

D7 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 7,318.64 | 1,158.45 | 2,717.19 | 3,677.71 | 10,462.75 | 1.19 | 1.61 | 1.70 | 1.66 | 1.35 |

D8 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.18 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 4,880.62 | 2,745.88 | 5,870.29 | 2,848.75 | 10,360.38 | 1.29 | 1.23 | 1.48 | 1.83 | 1.30 |

D9 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.17 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.15 | 4,342.77 | 2,487.10 | 2,787.89 | 10,619.09 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 1.46 | 1.51 | |||||

D10 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 9,118.51 | 1,948.72 | 8,783.82 | 3,256.55 | 11,247.70 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 1.58 | 1.91 | 1.23 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amini Parsa, V., Istanbuly, M.N., Kronenberg, J. et al. Urban Trees and Hydrological Ecosystem Service: A Novel Approach to Analyzing the Relationship Between Landscape Structure and Runoff Reduction. Environmental Management 73, 243–258 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01868-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01868-z