Abstract

Land use and land cover patterns are shaped by the interplay of human and ecological processes. Thus, heterogeneous cultural landscapes have developed, delivering multiple ecosystem services. To guarantee human well-being, the development of land use types has to be evaluated. Scenario development and land use and land cover change models are well-known tools for assessing future landscape changes. However, as social and ecological systems are inextricably linked, land use-related management decisions are difficult to identify. The concept of social-ecological resilience can thereby provide a framework for understanding complex interlinkages on multiple scales and from different disciplines. In our study site (Stubai Valley, Tyrol/Austria), we applied a sequence of steps including the characterization of the social-ecological system and identification of key drivers that influence farmers’ management decisions. We then developed three scenarios, i.e., “trend”, “positive” and “negative” future development of farming conditions and assessed respective future land use changes. Results indicate that within the “trend” and “positive” scenarios pluri-activity (various sources of income) prevents considerable changes in land use and land cover and promotes the resilience of farming systems. Contrarily, reductions in subsidies and changes in consumer behavior are the most important key drivers in the negative scenario and lead to distinct abandonment of grassland, predominantly in the sub-alpine zone of our study site. Our conceptual approach, i.e., the combination of social and ecological methods and the integration of local stakeholders’ knowledge into spatial scenario analysis, resulted in highly detailed and spatially explicit results that can provide a basis for further community development recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cultural landscapes were shaped over centuries by the interplay of human activity and nature, and are thus the epitome of social-ecological systems (SES) (Farina 2000; Hanspach et al. 2014). While environmental conditions generally determine the occurrence of land cover types (e.g., forest, grassland, and aquatic systems), human activities influence land cover through specific management schemes leading to a variety of land use types (Aranzabal et al. 2008; Foley et al. 2005). Heterogeneous (multifunctional) landscapes deliver multiple ecosystem services (e.g., recreation, food production, and climate regulation) and often contain habitats with high biodiversity (Plieninger et al. 2015).

However, cultural landscapes have been undergoing significant changes in the last decades with both intensification and abandonment as opposing developments (Aranzabal et al. 2008; Plieninger et al. 2014). Various requirements such as new areas for settlement, energy production, or nature conservation, and also loss of profitability lead to the replacement of traditional land use types and sometimes to rapid and pervasive transformation of landscapes (Plieninger et al. 2014). Hence, SES are subject to complex dynamics inducing land use and land cover (LULC) change. As land use types are embedded within a social framework, management decisions are determined by factors of different disciplines with more or less strong influence on decision-making processes (Hersperger and Bürgi 2009; Kizos et al. 2014).

The concept of resilience has proven valuable in understanding the dynamics of SES (Folke 2006; Folke et al. 2010; Schermer et al. 2016). Referring to resilience here as the “capacity of a socio-ecological system to retain the same functions, structures, and identities while facing disturbances” (Walker et al. 2004), the concept serves to identify driving forces and dynamics of the social and ecological sub-systems (Folke et al. 2010; Holling 2001; Wilson 2012). Several studies focus on the drivers behind land use change and their impact on landscapes and ecosystem services (Bürgi et al. 2004; Hanspach et al. 2014; Kizos et al. 2014). The identification of these interlinkages is in turn essential to forecast future developments (Hersperger et al. 2010). Driving forces can thereby be related to changes in socio-economic, political, technological, natural, or cultural systems (Brandt et al. 1999; Bürgi et al. 2004). Multiple processes act on various temporal and spatial scales with different effect according to the scale (Plieninger et al. 2015). The processes can include different institutions or stakeholders and are often mutually dependent and difficult to identify (e.g., changes in amount of EU subsidies and changes in local consumer behavior at the same time).

Evaluating the impact of these drivers on future land use is indispensable for sustainable land management (Lindborg et al. 2009). Scenarios as a tool to demonstrate plausible futures are thereby an appropriate method for minimizing uncertainty regarding the development of cultural landscapes (Soliva et al. 2008). Plausible scenarios for SES have to be developed depending on purpose and scale (IPBES 2016). For detailed results on land use and to comprehend various dynamics within the SES, (spatially) small-scale analyses are favorable (Hanspach et al. 2014). This might be even more necessary in mountain regions because of heterogeneous terrain.

However, only few studies link the concept of social-ecological resilience to impacts on land use (e.g. van Apeldoorn et al. 2011; Colding 2007), but most analyze foremost conceptual resilience thinking (e.g., Folke et al. 2010) or model LULC changes based on digital information (e.g., Verburg et al. 2010). Here, we apply a sequence of different steps embedded in the framework of resilience to determine future land use changes: (a) analysis of the SES (farming system) characteristics by literature research and expert interviews, (b) identification of key drivers that determine farmers’ land use decisions, (c) development of three scenarios, i.e., continuation of current trend, positive interpretation of key drivers with respect to farming conditions, and negative interpretation, (d) stakeholder workshop with local farmers, (e) spatial mapping of land use change. This sequence of different steps will produce plausible mapping results within the study site (Hanspach et al. 2014; Kizos et al. 2014; Oteros-Rozas et al. 2015). As biophysical and socio-economic conditions are heterogeneous across the landscape and the impact of drivers therefore more or less influential, explicit mapping enhances accuracy of results (Bürgi et al. 2004; Hanspach et al. 2014). Here, knowledge of local farmers on site-specific conditions was transformed into spatial information as farmers mapped land use changes in grassland management according to each scenario. The approach was applied to an Alpine valley in Austria.

In the following, we give a description of our study site, position our study within the resilience framework, and present the various steps of our methodological approach. We end by discussing the plausibility of our results and the practicability of the conceptual framework.

Materials and Methods

Description of Study Site

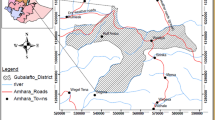

Our study site (Fig. 1) comprises the municipalities of Fulpmes and Neustift in the Stubai Valley in the Central Alps (Tyrol, Austria), part of the Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research network (LTSER platform “Tyrolean Alps” site Stubai). The valley is located about 30 km south of Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol. Around 8900 inhabitants live in Fulpmes (4250) and Neustift (4650) (Tiroler Landesregierung 2015). The study site covers around 265 km2 and ranges between 887 m a.s.l. on the valley floor and 3484 m a.s.l. at the highest elevation. About 73 km2 (27.5%) of the area is covered by forest, 23.7 km2 (8.9%) by managed and 40 km2 (15.1%) by abandoned grassland. Only 0.1% of the area is used as cropland (1% settlement, 47.4% non-usable area). A glacier offers year-round skiing facilities, which together with great scenic beauty makes the valley an attractive tourist destination in summer and winter. Tourism contributes economically to the municipalities in the valley by generating jobs as well as vitalizing the rural area in general. The proximity to Innsbruck prompts commuters to live in the valley and work in Innsbruck (Schermer et al. 2016; Statistik Austria 2015), which favours the economic situation of the Stubai Valley. A long tradition of adapted farming systems has led to the evolution of various grassland types in the Stubai Valley, providing several ecosystem services, high biodiversity, and contributing to the building of a cultural identity by inhabitants (Schirpke et al. 2013a, Soliva et al. 2008).

Resilience Concept

The concept of social-ecological resilience aims to identify and evaluate insecurities that affect the current structure or processes of a system (Folke et al. 2010). By recognizing the complexities, hierarchies, and dynamics of interlinked processes, it offers a way to conceptualize uncertainty (Darnhofer 2014; Jones and Tanner 2016). In this sense, it provides a suitable framework for simplification and the identification of a reduced set of relevant interactions that influence decision processes (Holling 2001; Quinlan et al. 2016). For the purpose of evaluating resilience, many studies use surrogates such as the resilience of ecosystem service provision (Biggs et al. 2012), the transformation capacity of farms (Darnhofer et al. 2010), or the multifunctionality of rural communities (Wilson 2010, 2012). Wilson (2010) defined community resilience as the capacity of a rural community (i.e., system) to absorb shocks, and the ability to reorganize in times of change. A community can thus show strong resilience (strong multifunctionality), or weak resilience (weak multifunctionality), and thus vulnerability in its development over time (Wilson 2010, 2012). Here, we focus on a farming system on the communal level and quantify respective LULC changes in future (Fig. 2).

Conceptual approach embedded in the framework of resilience, after Wilson (2012)

Methodological Framework

The study was implemented in the Stubai Valley (Neustift) in Tyrol/Austria and consisted of the following steps:

Characterization of farming system

First, research reports, scientific publications, public government documents, and official agricultural statistics were analyzed to emphasize mountain grassland farming systems in general, and to identify characteristics of the local farming systems (Appendix). These data were compiled in two reportsFootnote 1: (1) The country report covers the results of a desk research on national scientific literature and includes information on the general relevance of mountain permanent grasslands, specific societal claims, formal governance mechanisms, public support systems, and suggestions for further interventions. (2) The case study report contains a description of the region, arrangement of land use types, and statistical data such as livestock units, economic situation of households as well as a description of relevant agricultural policy measures. These data were complemented by expert interviews, which gave more information about relevant actors and the current trends in agricultural development and land use at our study site.

Expert interviews

Semi-structured interviews with local key informants were conducted to disclose information on local farming systems and—when possible—double-checked against published data. This allowed us to discern important key drivers that influence the farming system. A key informant (expert) is considered to be a person with specific knowledge in a certain field of activity and functions as representative of a group (Bogner and Menz 2002; Flick 2007). Here, key informants had a profound knowledge of land use dynamics at the study site. They were either represented by members of the advisory service and the Chamber of Agriculture or are farmers themselves and thus have inside knowledge of farming systems and mechanisms. The sample was based on five persons: two farmers in Neustift, one of them being the head of the Ortsbauernrat (municipal farmers’ association); a third farmer from the nearby village of Mieders adds a reflexive perspective; the fourth farmer was the former chamber president, and the fifth key informant came from the advisory service.

The semi-structured interviews were centered around the historical development and present modes of farming systems in the valley and on the alpine pastures. Further questions were related to the factors influencing the farming practices and the future perspectives of farming in the Stubai Valley. The content-analytical evaluation of the interviews with key informants was realized according to Phillip Mayring (Mayring 2014). The text material was structured into the following inductive and deductive developed categories: labor organization, products, and farming system and land use.

Identification of key drivers

Key drivers that influence the system’s dynamics in Neustift have been extracted from the structured text material of the expert interviews. Single key drivers have been clustered into different categories (see Table 1). The results of all categories were again structured into the three forms of capital (Table 1) according to Wilsons’ framework of community resilience (Wilson 2010, 2012).This framework explicitly emphasizes (rural) community-environmental interlinkages, and relates key drivers of resilience to economic, social (including political and cultural) and environmental capital.

Scenario development

Based on the identified key drivers from the expert interviews (see Table 1), three explorative scenarios (IPBES 2016) were developed. Here, scenarios are applied to examine plausible futures of complex systems under the assumption that key drivers are changing in a positive or negative way (with respect to farming conditions) and the current trend continues (Fig. 2). A comprehensive scenario includes biological, physical as well as human factors and is grounded in data, information, experiences, and estimations (Henrichs et al. 2010; van Notten et al. 2003). The storyline for each scenario was conducted by focusing on decision making processes of farmers concerning the management of grassland ecosystems (i.e., interpretation of key drivers): the trend scenario describes a possible future of the Stubai Valley following the current trend. Consequently, a positive and a negative storyline for the study region were developed to present two contrasting, but plausible futures. The time horizon is 2050 to include farm succession as a driver of land use change (several farmers will retire within the next 25 years) (e.g., MacDonald et al. 2000).

Stakeholder workshop

To assess the dimension of future land use change the prior developed scenarios were discussed with local stakeholders (see also Henrichs et al. 2010). First, a local expert (former researcher at the University of Innsbruck, active farmer) checked scenarios for plausibility as a pre-test before a participatory workshop was held with local Neustift farmers. The plausibility of the refined scenarios was again discussed with participants at the workshop; the scenarios correspond to the indications for participatory processes published by Henrichs et al. (2010). Farmers were invited by the head of the municipal farmers’ association (Ortsbauernobmann) with the aim of having a cross-section of the Neustift farming community in attendance. In total, nine farmers were present; four were over 50years, four between 40 and 50 years, and one farmer was under 35 years of age. All farmers generate additional income outside their farm, mainly within the tourism sector. The farmers’ grassland sites are dispersed throughout the Stubai Valley and cover the major part of our study site. Moreover, the farmers at least know the other sites. After presentation of the three scenarios, farmers discussed the plausibility of each one. Scenarios consequently have been adapted and mapping of land use changes was done based on the refined scenarios.

Mapping of land use changes

During the stakeholder workshop local farmers mapped likely land use changes according to each scenario with a pen-and-paper approach. For this purpose, the most recent orthophoto of the Stubai Valley (year 2013) was used as the basis, wherein farmers marked estimated changes with colored text markers. Farmers further added the information into which LULC type the patch will most likely transform. This process was done for all three scenarios.

The information on land use change gathered in the workshop was mapped in ArcGIS 10.1, and quantitatively analyzed. In the scenario maps, we reclassified abandoned grassland into forest when it was located below the potential treeline (~2300 m a.s.l.). Although a severe downshift in the current treeline was recorded in the Alpine region due to long-lasting anthropo-zoogenic impacts (Pecher et al. 2011), abandonment of summer pastures and the response of plants to rising temperatures will result in an upshift in the potential treeline in future (Vittoz et al. 2008).

In order to better compare LULC changes among scenarios, we used ecoregions, i.e., landscape units that share certain site characteristics such as topography, climate as well as basic socio-ecological conditions (Schirpke et al. 2012; Tasser et al. 2009). We differentiated four ecoregions: (1) valley floor (<1500 m a.s.l.), (2) forest belt, and (3) sub-alpine grassland (both between 1500 and 2300/2400 m a.s.l. with the forest belt generally at a lower elevation), and (4) alpine/nival belt (>2300/2400 m a.s.l.).

Results

Farming System (Step a)

In the following, characteristics of the farming system are presented.

Labor organization

Since the 1970s structural change has led to a decrease in employment in the agricultural sector and an increase in the tourism sector with regard to the economic situation in the Stubai Valley. This development is favoured by the valley’s environmental conditions and geographic proximity to Innsbruck (commuters). Parallel thereto, the structural change causes a shift in agricultural working structures, i.e., from main-income farming (15.5%) to part-time farming (72.6%, 2010 for Neustift, others structures are collective farms and farm associations) (Statistik Austria 2011).

However, structural change (i.e., abandonment of farms) is less pronounced in Neustift than at the state or national level in Austria. Within the last 10 years the number of farms decreased from 181 to 168, i.e., −7.2% (Statistik Austria 2011). The persistence of part-time managed farms might be attributed to pluri-active income possibilities, mainly within the tourism sector (key informants). The main income in part-time farming is obtained either on-farm (e.g., agri-tourism, direct marketing of agricultural products), or off-farm (e.g., working in the tourism sector in the valley, or commuting to Innsbruck).

Production system

Farming systems in the Stubai Valley can be separated into farms with animal husbandry focusing on either cattle, cows or sheep (and goats) and farms without animal husbandry, namely focusing on grassland production.

Cattle/cows

The main production system in the Stubai Valley is cattle breeding in combination with milk production. Main-income farmers with a focus on dairy cows keep their animals (mainly Holstein-Fresian) in barns in the valley (Tasser et al. 2012a). Dairy cows on alps become extinct as these cows are too heavy and their energy demand cannot be covered by mountain grasslands alone. However, suckler cows and breeding stocks are still kept on alps in summer and autumn. Common breeds are Brown Swiss and “Tiroler Grauvieh”, which are well adapted to mountainous terrain. Many farmers build their farming identity by breeding and are members of breeding associations (key informant).

Since 2013 dairy farmers have been delivering milk to Milchhof Sterzing in South Tyrol (Italy), which pays a high price for milk as compared with most other dairies in the European Union (Erker 2015). This special situation has stabilized the number of dairy farms in the Stubai Valley over the last three years (key informant). However, new EU regulations for animal husbandry (Austrian Federal Law Gazette II No. 219/2010) require barn modification with regard to free run instead of tethering. A transition period exists until 2020, but costs for a new barn run up to € 300.000 and space for modifications is limited. Consequently, it is to be expected that part-time farmers with few dairy cows and low milk production will stop farming as modifications are not profitable. As these farmers have mainly kept their cows on mountain pastures during the summer, this can result in abandonment of such pastures. Overall, the cattle stocking rate (LU ha−1 agricultural land) in the region is low, namely 0.6 LU ha−1 in 2014 (Bundesanstalt für Agrarwirtschaft 2015).

Sheep

Sheep and goats are often kept in combination with cattle. However, farmers with sheep only are mostly part-time farmers as this system is less labor-intensive than cattle. An increase in sheep and goat farming was recorded since 1970 (Tasser et al. 2012b), which can be due to changes in consumer demands as, for instance, an increase in allergies (cow milk). A majority of sheep farmers conduct stock breeding with a focus on meat production, whereas the breeding objective was formerly size and mobility. The dominant breed is the Tiroler Bergschaf (Österreichischer Bundesverband für Schafe und Ziegen 2016). It shows good surefootedness and is therefore highly suitable for grazing on unpassable grassland often above the treeline.

Farming systems and land use

Management schemes and land use can be differentiated according to altitude. In general, grassland steepness, proximity, and accessibility to the farm influence management intensity.

Valley

Grassland on the valley floor undergoes one to four cuts, and some sites are additionally grazed in spring and autumn. Meadows on hillsides are mown between one and two times (Fondevilla et al. 2016). Grassland is fertilized and produces hay or silage. Intensively used grassland is cut for the first time in mid-May, resulting in fodder with a high protein content (for dairy farming). Fertilization differs between solid and liquid manure, due to either free-run or tethering barns. With new barn requirements, the manure system shifts from solid to liquid manure. This results in larger amounts (volume) of manure, and in turn might increase the number of times the field is fertilized. In the valley there are no pastures that see year-round use. Communal areas are used as forest pastures.

(Sub-)alpine meadows

Today only few mown meadows exist >1600 m a.s.l. They have to be accessible and usable for machines (e.g., slope) and are mown once a year. They are always managed in combination with grazing. The majority of farmers participate in agri-environmental schemes (key informant, Tirol Atlas 2014); these are funding schemes for nature conservation measures, e.g., late mowing.

(Sub-)alpine pastures

Alpine pastures are stocked with either cattle or sheep, or both. Sheep pastures are mostly above 2000 m a.s.l. in the (sub-)alpine zone without consistent shepherding. Cattle pastures are usually near alpine huts and located below 2000 m a.s.l. Alpine huts with animal husbandry are generally accessible by car. They have catering facilities that provide the economic basis and main income (key informant). However, hygiene regulations cause a decline in the number of managed huts. Some (sub-)alpine pastures are collective pastures used by on average five to seven part-time farmers, as mentioned by key informants. They are extensively used, mainly grazed by sheep and young stock. Milking is still done on only a few pastures.

It can be concluded that agriculture plays only a minor direct economic role in the Stubai Valley today. Nevertheless, the existing vital farming structures and a variety of different applied management schemes contribute to vitalization of the valley. The preservation of traditional cultural landscapes remains important, especially for summer tourism.

Key Drivers (Step b)

The identified key drivers were grouped according to Wilson (2010) and are presented in Table 1.

Narratives of Scenarios (Step c)

Based on identified key drivers, storylines for scenarios were developed and checked for plausibility by farmers during the stakeholder workshop (step d). The most important outcomes of the plausibility discussion regarded climate change as a driver and the general influence of key drivers (see Discussion). Consequently, the negative scenario was adapted and the interpretation of key drivers relativized. The negative scenario presented here already illustrates the final adapted scenario. Overall, this resulted in more similar scenarios. The following shortened narratives of the scenarios were used in the stakeholder workshop.

Trend scenario

Economically, farming activities show little importance. Nevertheless, the community does value the ecological and societal services provided by the farming community. A diversified but rather extensive agriculture is mainly realized in part-time work, as tourism and commuting to Innsbruck provide good employment opportunities. Pluri-active income is important and direct payments guarantee a substantial part of it, but also demand administrative efforts. Identity building is still shaped by the local social farming institutions and basic synergies between agriculture and tourism are exploited. The continuing trend is to a slow intensification on the valley floor and a slight increase in abandonment of grassland at higher altitudes. However, even with slowly ongoing structural change the farming system is able to retain an open cultural landscape.

Positive scenario

The diversified agriculture within the valley efficiently cooperates with the tourism industry, e.g., providing part-time jobs, markets for local products, or clients for holidays on a farm. Still, part-time farming remains very important for supplementary farm income, but also direct payments contribute to a fixed income for farmers. Therein, self-regulating measures support collaboration among farmers. Farm succession is guaranteed and financial support/advice helps to react to new EU regulations. Even if the general development objective of the community focuses on tourism, agricultural activities are valued. Identity and overall attitude towards farming are heavily influenced by several social farming organizations in a mixture of tradition and innovation.

Negative scenario

Farming has little importance for food production and instead serves to sell an image for tourism purposes. Some farms generate income with holiday on farms or farm visits. Alpine pastures in certain areas function as living museums. Due to budget constraints of EU agricultural policy, direct payments do not secure an income. Many small-scale farmers have difficulties coping with new EU barn regulations and will retire. As tourism is promoted via the “new wilderness”, ecological and social services provided by farming are no longer valued by the community. Social farming organizations have lost their influence on identity building as fewer farmers continue farming.

Land Use and Land Cover Changes (Step e)

Currently, managed grassland is mainly located on the valley floor (40%) and in the sub-alpine zone (48%), whereas 98% of the abandoned land can be found in the ecoregions at higher elevation (sub-alpine zone and alpine/nival belt). The trend scenario shows that most changes (74%) occur in the valley with a conversion of grassland into cropland; a slight abandonment of grassland and thus an increase in forest area in the sub-alpine zone (21% of changes) (Fig. 3). In the positive scenario LULC change is greatest on the valley floor (45%) and in the forest belt (42%). Similar to the trend scenario, grassland will be converted into cropland on the valley floor (Fig. 3). The conversion from forest back to grassland within ecoregions two (forest belt) and three (sub-alpine zone) in the positive scenario can be explained by reactivated forest pastures. In the negative scenario only abandonment was recorded, with highest values in the zone of sub-alpine meadows and pastures (73% of changes) (Fig. 3).

In total, LULC changes in the scenarios over all ecoregions range between 187 ha in the trend scenario and 426 ha in the negative scenario (254 ha in the positive scenario). In comparison with the total managed grassland area in our study region today (~2370.6 ha), positive and negative changes in grassland area range between 7.9% (trend) and 17.1% (negative), with the positive scenario in between (10.7%) (Fig. 3).

Changes in LULC (current—2050) within the ecoregions (1) valley, (2) forest belt, and (3) sub-alpine zone for the trend, positive and negative scenarios (no changes were recorded for the (4) alpine/nival belt). Within the diagrams abandonment of grassland results directly in forest (transition state “abandoned land” skipped over). Maps of the Stubai Valley show location of LULC changes mapped by farmers for each scenario. Natural afforestation (mapped in pink) results from grassland already abandoned today

Discussion

Plausibility of Results

Agricultural intensification under the trend and positive scenarios can be linked to the predicted increase in temperature (+1.5 to 2 K), which enables cultivation of crops at the lower elevations of the valley (Gobiet et al. 2014; Schirpke et al. 2013a). However, despite higher temperatures and extreme events (climate change) causing the farmers to irrigate their sites (whenever possible), they did not intend to change their farming systems (see also Lamarque et al. 2014) by changing their management or converting grassland to cropland as they rely on fodder production for the dairy farming systems. Further, for the farmers, tourism is the most important issue. They stressed the fact that as long as tourists visit the valley, they will manage grassland sites to support a traditional and touristic picture (see also Lindemann-Matthies et al. 2010; Schirpke et al. 2013b). Grassland management on most sites will thus be continued and large-scale afforestation is not an option (as originally suggested in the negative scenario). On contrary, farmers see the possibility of recultivating forest into pastures or meadows if regulations for former managed areas are added to the currently very strict forest laws. Moreover, a favorable consumer market (demand for local products) and subsidies for extensively used pastures were assumed. In both the trend and the positive scenarios farmers emphasized the importance of having several sources of income (pluri-activity) and their self-perception as farmers (e.g., Kvakkestad et al. 2015) for the continuation of grassland management at higher elevations, including the forest belt, the sub-alpine and the alpine/nival zones (Darnhofer et al. 2010; Tasser et al. 2012a). In line with other studies (e.g., Lindborg et al. 2009), reactivated pastures and cropland were mostly located on already historically used land. The negative scenario assumed a reduction in subsidies and direct payments within the Common Agricultural Policy (Hanspach et al. 2014) as well as a trend in consumer behavior to cheaper and non-local products (Schermer et al. 2016; Soliva et al. 2008). Farmers react by ceasing to manage grassland in all ecoregions (Loibl and Walz 2010). As the management of sub-alpine meadows and pastures is favoured by subsidies, loss of these payments is seen to have its greatest influence in this zone (Lindborg et al. 2009; MacDonald et al. 2000; Schirpke et al. 2013a).

Overall, farmers do not expect distinct changes in the trend and positive scenarios. Contrasting to past large-scale abandonment or intensification processes in many alpine regions (Egarter Vigl et al. 2016), significant changes in LULC have not occurred. This can first be linked to tourist demand, proximity to Innsbruck, and thus employment possibilities outside the agricultural sector (see also Fondevilla et al. 2016; MacDonald et al. 2000). Second, historical assessment of landscape patterns in the Stubai Valley shows that significant LULC changes already took place between 1950 and 1985 (Egarter Vigl et al. 2016), and we are therefore at the end of a large-scale transformation process. However, still considerable conversion of grassland into forest (17%) was recorded for the negative scenario.

Changes in LULC induce a shift in ecosystem functions (and, after human demand, in ecosystem services) as they rely on certain ecosystem processes (e.g., nutrient cycle) provided by habitat types in varying extent (Lamarque et al. 2011). As an example, with the conversion from grassland to forest, forage quantity will decrease (or diminish) while the amount of carbon storage will increase (Burkhard et al. 2012). Therefore, impacts of LULC change must be further analyzed for their effects on multifunctional ecosystem service provision.

Conceptual Approach

Less an explicit tool and more a guiding framework, the concept of social-ecological resilience can frame analysis of future SES development (Darnhofer 2014; van Apeldoorn et al. 2011). By recognizing the complexity of drivers and scales that influence a system’s resilience, use of the resilience concept in combination with future land use assessment proved to be successful. Application of the resilience framework contributed positively to the structuring of social, economic and environmental interlinkages and increased understanding of the system’s dynamics. We recognized the importance of focusing on a limited set of relevant indicators and thus simplifying the complexity of the system, especially in the case of our participatory approach (Helming et al. 2011). With farmers as our target group and the evaluation of impacts on respective land use management decisions, we indirectly included other scales of the SES such as e.g., institutional regulations or policy design.

Our methodological approach, namely (a) characterization of the SES (farming system) by literature research and expert interviews, (b) identification of key drivers, (c) scenario development, (d) stakeholder workshop, and (e) mapping of LULC change, resulted in a high level of detailed and spatially explicit outcomes of possible future grassland land use. By applying both scientific methods and local knowledge—first within expert interviews and second with the validation of the future scenarios by local stakeholders, we gained a deep insight into the farming system and therefore enhanced the probability of evaluating possible future LULC changes (Hanspach et al. 2014; Oteros-Rozas et al. 2015; Plieninger et al. 2013). Nevertheless, deriving from an approach of qualitative social research (expert interviews), the results of this study do not claim to be representative (see e.g., Kruse 2014). However, we claim that the same methodology could be applied in other areas to map possible futures. For its application it is always the local context and the access to the field, which are decisive for the identification of participants for the expert interviews and the stakeholder workshop; and thus, the results. However, our approach shows a high demand on time and labor and might therefore not be applicable when resources are limited, especially in regions with a great diversity in farming systems.

Conclusion

LULC patterns are the result of social and ecological processes and one component of social-ecological resilience. Here, we used the framework of resilience to ensure that landscape scenarios contain all relevant (multi-sectoral) drivers that influence future land use. With our transdisciplinary methodological approach, we translated tacit local knowledge into spatial information, which allowed us to evaluate quantitative and spatially explicit results of grassland development. We believe that our study could serve as a basis for elaborating practical solutions and recommendations for community development or policy design to guide land use and consequently ecosystem service provision in future (Plieninger and Bieling 2013).

Notes

For details see the country reports on the project homepage: http://www.project-regards.org/Publications.html

References

Aranzabal Ide, Schmitz MF, Aguilera P, Pineda FD (2008) Modelling of landscape changes derived from the dynamics of socio-ecological systems. Ecol Indic 8(5):672–685. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2007.11.003

Beniston M (2012) Impacts of climatic change on water and associated economic activities in the Swiss Alps. J Hydrol 412–413:291–296. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.06.046

Biggs R, Schlüter M, Biggs D, Bohensky EL, BurnSilver S, Cundill G, Dakos V, Daw TM, Evans LS, Kotschy K, Leitch AM, Meek C, Quinlan A, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Robards MD, Schoon ML, Schultz L, West PC (2012) Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annu Rev Environ Resour 37(1):421–448. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-051211-123836

Bogner A, Menz W (2002) Das theoriegenerierende experteninterview. erkenntnisinteresse, wissensformen, interaktion. In: Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W (eds) Das Experteninterview: theorie, Methode, Anwendung. Springer, Wiesbaden, p 33–70

Brandt J, Primdahl J, Reenberg A (1999) Rural land-use and landscape dynamics—analysis of ‘driving forces’ in space and time. In: Krönert R, Baudry J, Bowler IR, Reenberg A (eds) Land-use changes and their environmental impact in rural areas in Europe. UNESCO, Paris, p 81–102

Bundesanstalt für Agrarwirtschaft (2015) Rinderbestände auf Bezirksebene. Rinder je Rinderhalter nach politischen Bezirken. http://www.agraroekonomik.at/index.php?id=regrinderbest. Accessed 2 Jun 2016

Bürgi M, Hersperger AM, Schneeberger N (2004) Driving forces of landscape change—current and new directions. Landsc Ecol 19:857–868

Burkhard B, Kroll F, Nedkov S, Müller F (2012) Mapping ecosystem service supply, demand and budgets. Ecol Indic 21:17–29. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.06.019

Colding J (2007) ‘Ecological land-use complementation’ for building resilience in urban ecosystems. Landsc Urban Plan 81(1-2):46–55. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2006.10.016

Darnhofer I (2014) Resilience and why it matters for farm management. Eur Rev Agric Econ 41(3):461–484. doi:10.1093/erae/jbu012

Darnhofer I, Fairweather J, Moller H (2010) Assessing a farm’s sustainability: insights from resilience thinking. Int J Agric Sustain 8(3):186–198. doi:10.3763/ijas.2010.0480

Egarter Vigl L, Schirpke U, Tasser E, Tappeiner U (2016) Linking long-term landscape dynamics to the multiple interactions among ecosystem services in the European Alps. Landsc Ecol 10.1007/s10980-016-0389-3

Erker (2015) Milchhof Sterzing steigert Umsatz und Milchauszahlungspreis. http://www.dererker.it/de/news/762-milchhof-sterzing-steigert-umsatz-und-milchauszahlungspreis.html. Accessed 7 Jun 2016

Farina A (2000) The cultural landscape as a model for the integration of ecology and economics. BioScience 50(4):313–320

Flick U (2007) Designing qualitative research. SAGE Publications Ltd, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Qualitative Research Kit

Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, Chapin SF, Coe MT, Daily GC, Gibbs HK, Helkowski JH, Holloway T, Howard EA, Kucharik CJ, Monfreda C, Patz JA, Prentice IC, Ramankutty N, Snyder PK (2005) Global consequences of land use. Science 309(5734):570–574. doi:10.1126/science.1111772

Folke C (2006) Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob Environ Change 16(3):253–267. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

Folke C, Carpenter SR, Walker B, Scheffer M, Chapin T, Rockström J (2010) Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol Soc 15(4):20

Fondevilla C, Àngels Colomer M, Fillat F, Tappeiner U (2016) Using a new PDP modelling approach for land-use and land-cover change predictions: a case study in the Stubai Valley (Central Alps). Ecol Model 322:101–114. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.11.016

Gobiet A, Kotlarski S, Beniston M, Heinrich G, Rajczak J, Stoffel M (2014) 21st century climate change in the European alps—a review. Sci Total Environ 493:1138–1151. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.050

Hanspach J, Hartel T, Milcu AI, Mikulcak F, Dorresteijn I, Loos J, Wehrden H von, Kuemmerle T, Abson D, Kovács-Hostyánszki A, Báldi A, Fischer J (2014) A holistic approach to studying social-ecological systems and its application to southern Transylvania. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-06915-190432

Helming K, Diehl K, Kuhlman T, Jansson T, Verburg PH, Bakker M, Perez-Soba M, Jones L, Johannes Verkerk P, Tabbush P, Breton Morris J, Drillet Z, Farrington J, LeMouël P, Zagame P, Stuczynski T, Siebielec G, Wiggering H (2011) Ex ante impact assessment of policies affecting land use, Part B: application of the analytical framework. Ecol Soc 16(1): 29. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss1/art29/

Henrichs T, Zurek M, Eickhout B, Kok K, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Ribeiro T, van Vuuren D, Volkery A (2010) Scenario development and analysis for forward-looking ecosystem assessment. In: Ash N, Blanco H, Brown C, Garcia K, Henrichs T, Lucas N, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Simpson RD, Scholes R, Tomich TP, Vira B, Zurek M (eds) Ecosystems and human well-being. A manual for assessment practitioners. Island Press, Washington, p 151–220

Hersperger AM, Bürgi M (2009) Going beyond landscape change description: quantifying the importance of driving forces of landscape change in a central Europe case study. Land Use Policy 26(3):640–648. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.08.015

Hersperger AM, Gennaio M-P, Verburg PH, Bürgi M (2010) Linking land change with driving forces and actors: four conceptual models. Ecol Soc 15(4):1–17

Holling CS (2001) Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 4(5):390–405. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2016) Summary for policymakers of the methodological assessment of scenarios and models of biodiversity and ecosystem services (deliverable 3 ©). IPBES/4/L.4:1–21

Jones L, Tanner T (2016) ‘Subjective resilience’: using perceptions to quantify household resilience to climate extremes and disasters. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-016-0995-2

Kizos T, Detsis V, Iosifides T, Metaxakis M (2014) Social capital and social-ecological resilience in the asteroussia mountains, Southern Crete, Greece. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-06208-190140

Kruse J (2014) Qualitative Interviewforschung. Ein integrativer Ansatz. Beltz, Weinheim

Kvakkestad V, Rørstad PK, Vatn A (2015) Norwegian farmers’ perspectives on agriculture and agricultural payments: between productivism and cultural landscapes. Land Use Policy 42:83–92. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.07.009

Lamarque P, Lavorel S, Mouchet M, Quetier F (2014) Plant trait-based models identify direct and indirect effects of climate change on bundles of grassland ecosystem services. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(38):13751–13756. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216051111

Lamarque P, Quétier F, Lavorel S (2011) The diversity of the ecosystem services concept and its implications for their assessment and management. Comptes Rendus Biologies 334(5-6):441–449. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2010.11.007

Lindborg R, Stenseke M, Cousins SA, Bengtsson J, Berg Å, Gustafsson T, Sjödin NE, Eriksson O (2009) Investigating biodiversity trajectories using scenarios—lessons from two contrasting agricultural landscapes. J Environ Manage 91(2):499–508. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.09.018

Lindemann-Matthies P, Briegel R, Schüpbach B, Junge X (2010) Aesthetic preference for a Swiss alpine landscape: the impact of different agricultural land-use with different biodiversity. Landsc Urban Plan 98(2):99–109. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.07.015

Loibl W, Walz A (2010) Generic regional development strategies from local stakeholders’ scenarios—an alpine village experience. Ecol Soc 15(3):3

MacDonald D, Crabtree J, Wiesinger G, Dax T, Stamou N, Fleury P, Gutierrez Lazpita J, Gibon A (2000) Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: environmental consequences and policy response. J Environ Manage 59(1):47–69. doi:10.1006/jema.1999.0335

Mayring P (2014) Qualitative content analysis. theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Beltz, Klagenfurt

Österreichischer Bundesverband für Schafe und Ziegen (2016) Tiroler Bergschaf. http://alpinetgheep.com/tiroler-bergschaf.html. Accessed 2 Jun 2016

Oteros-Rozas E, Martín-López B, Daw TM, Bohensky EL, Butler JR, Hill R, Martin-Ortega J, Quinlan A, Ravera F, Ruiz-Mallén I, Thyresson M, Mistry J, Palomo I, Peterson GD, Plieninger T, Waylen KA, Beach DM, Bohnet IC, Hamann M, Hanspach J, Hubacek K, Lavorel S, Vilardy SP (2015) Participatory scenario planning in place-based social-ecological research: insights and experiences from 23 case studies. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-07985-200432

Pecher C, Tasser E, Tappeiner U (2011) Definition of the potential treeline in the European Alps and its benefit for sustainability monitoring. Ecol Indic 11(2):438–447. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.06.015

Plieninger T, Bieling C (2013a) Resilience-based perspectives to guiding high-nature-value farmland through socioeconomic change. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-05877-180420

Plieninger T, Bieling C, Ohnesorge B, Schaich H, Schleyer C, Wolff F (2013b) Exploring futures of ecosystem services in cultural landscapes through participatory scenario development in the Swabian Alb, Germany. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-05802-180339

Plieninger T, Kizos T, Bieling C, Le Dû-Blayo L, Budniok M-A, Bürgi M, Crumley CL, Girod G, Howard P, Kolen J, Kuemmerle T, Milcinski G, Palang H, Trommler K, Verburg PH (2015) Exploring ecosystem-change and society through a landscape lens: recent progress in European landscape research. Ecol Soc 20(2):5

Plieninger T, van der Horst, Dan, Schleyer C, Bieling C (2014) Sustaining ecosystem services in cultural landscapes. Ecol Soc. doi:10.5751/ES-06159-190259

Quinlan AE, Berbés-Blázquez M, Haider LJ, Peterson GD, Allen C (2016) Measuring and assessing resilience: broadening understanding through multiple disciplinary perspectives. J Appl Ecol 53:677–687. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12550

Schermer M (2015) From “Food from Nowhere” to “Food from Here:” changing producer–consumer relations in Austria. Agric Hum Values 32(1):121–132. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9529-z

Schermer M, Darnhofer I, Daugstad K, Gabillet M, Lavorel S, Steinbacher M (2016) Institutional impacts on the resilience of mountain grasslands: an analysis based on three European case studies. Land Use Policy 52:382–391. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.009

Schirpke U, Leitinger G, Tappeiner U, Tasser E (2012) SPA-LUCC: Developing land-use/cover scenarios in mountain landscapes. Ecol Inform 12:68–76. doi:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.09.002

Schirpke U, Leitinger G, Tasser E, Schermer M, Steinbacher M, Tappeiner U (2013a) Multiple ecosystem services of a changing Alpine landscape: past, present and future. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage 9(2):123–135. doi:10.1080/21513732.2012.751936

Schirpke U, Tasser E, Tappeiner U (2013b) Predicting scenic beauty of mountain regions. Landsc Urban Plan 111:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.11.010

Soliva R, Rønningen K, Bella I, Bezak P, Cooper T, Flø BE, Marty P, Potter C (2008) Envisioning upland futures: stakeholder responses to scenarios for Europe’s mountain landscapes. J Rural Stud 24(1):56–71. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.04.001

Statistik Austria (2011) Ein Blick auf die Gemeinde Neustift im Stubaital <70334>. Land- und forstwirtschaftliche Betriebe und Flächen nach Erwerbsart. http://www.statistik.at/blickgem/blick5/g70334.pdf

Statistik Austria (2015) Abgestimmte Erwerbsstatistik 2013—Erwerbspendler nach Pendelziel. http://www.statistik.at/blickgem/ae3/g70334.pdf

Tasser E, Pecher C, Schreiner K, Tappeiner U (2012a) Wirtschaft schafft Landschaft. In: Tasser E, Schermer M, Siegl G, Tappeiner U (eds) Wir Landschaftsmacher. Vom Sein und Werden der Kulturlandschaft in Nord-, Ost- und Südtirol. Athesia, Bozen, p 103–147

Tasser E, Ruffini FV, Tappeiner U (2009) An integrative approach for analysing landscape dynamics in diverse cultivated and natural mountain areas. Landsc Ecol 24(5):611–628. doi:10.1007/s10980-009-9337-9

Tasser E, Schermer M, Siegl G, Tappeiner U (eds) (2012b) Wir Landschaftsmacher. Vom Sein und Werden der Kulturlandschaft in Nord-, Ost- und Südtirol. Athesia, Bozen

Tirol Atlas (2014) Zahlungen im Rahmen der gemeinsamen Agrarpolitik der EU (2014). http://tirolatlas.uibk.ac.at/maps/interface/thema.py/sheet?lang=de;menu_id=248

Tiroler Landesregierung (2015) Regionsprofil Stubaital. Planungsverband 21. Statistik 2015. https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/statistik-budget/statistik/downloads/Regionsprofile/Stat_profile/Planungsverbaende/PV_Stubaital.pdf

van Apeldoorn DirkF, Kok K, Sonneveld MP, Veldkamp T (2011) Panarchy rules: rethinking resilience of agroecosystems, evidence from dutch dairy-farming. Ecol Soc 16(1):39

van Notten PhilipWF, Rotmans J, van Asselt MarjoleinBA, Rothman DS (2003) An updated scenario typology. Futures 35(5):423–443. doi:10.1016/S0016-3287(02)00090-3

Verburg PH, van Berkel DerekB, van Doorn AnneM, van Eupen M, van den Heiligenberg HarmARM (2010) Trajectories of land use change in Europe: a model-based exploration of rural futures. Landsc Ecol 25(2):217–232. doi:10.1007/s10980-009-9347-7

Vittoz P, Rulence B, Largey T, Freléchoux F (2008) Effects of climate and land-use change on the establishment and growth of cembran pine (pinus cembra l.) over the altitudinal treeline ecotone in the central swiss alps. Arct Antarct Alp Res 40(1):225–232. doi:10.1657/1523-0430(06-010)[VITTOZ]2.0.CO;2

Walker B, Holling C, Carpenter SR, Kinzig A (2004) Resilience, adaptability and transformability in sociol-ecological systems. Ecol Soc 9(2):5

Wilson G (2010) Multifunctional ‘quality’ and rural community resilience. Trans Inst Br Geogr 35(3):364–381

Wilson GA (2012) Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision-making. Geoforum 43(6):1218–1231. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.03.008

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their contribution to improve the manuscript, and farmers of Neustift for their support. This work was supported by the ERA-Net BiodivERsA, with the national funder FWF Der Wissenschaftsfond (I 1056, I 1055), as part of the 2011–2012 BiodivERsA call for research proposals (project REGARDS) and by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy with the HRSM—cooperation project KLIMAGRO. This study was conducted at the LTER site “Stubai Valley” (LTSER platform “Tyrolean Alps”). Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Marina Kohler and Rike Stotten contributed equally to this work.

Melanie Steinbacher was previously employed at the Department of Sociology, Mountain Agricultural Research Centre, University of Innsbruck, Universitätsstrasse 15, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kohler, M., Stotten, R., Steinbacher, M. et al. Participative Spatial Scenario Analysis for Alpine Ecosystems. Environmental Management 60, 679–692 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0903-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0903-7