Abstract

Wet/dry mapping provides a low-cost, comprehensive snapshot for monitoring flow conditions in rivers with interrupted perennial (spatially intermittent) surface flow. When used in conjunction with more traditional point-specific stream flow or groundwater measurements, it provides a better understanding of hydrologic systems at the broad landscape or watershed scale. Through use of trained volunteers, we mapped reaches with surface water during the driest time of year to track annual variation in length and location of perennial flow. Data from 12 years of wet/dry mapping on the San Pedro River in Arizona, USA, showed 62 reaches with surface flow in every year, totaling 32% of the river length through the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. They also show areas with high year-to-year variation in flow length, which indicate changes in local groundwater conditions and may provide early warning of ecological changes. Data and maps from this project have been useful for a wide variety of conservation, management, and research efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perennial streams and their associated riparian communities have contracted or disappeared in arid and semi-arid regions around the world, the result of surface diversions and groundwater extraction (FitzHugh and Richter 2004; Postel 2000; Stromberg and others 2004). The state of Arizona, alone, has lost approximately 35% of its perennial stream flow in the past 200 years (Brown and others 1981). The loss of streams and rivers has large social, economic, and ecological consequences, so managers and concerned citizens seek ways to track the status of these systems.

There is also growing scientific interest in the ecology of spatially-intermittent streams and the lessons they offer for understanding the effects of drought as a disturbance regime, especially in anticipation of changing climates (Humphries and Baldwin 2003; Larned and others 2010; Sponseller and others 2010). Expansion and contraction in the length of wetted reaches can cause large variations in water quality, the composition of aquatic and riparian communities, and metapopulation dynamics, so ecological studies of spatially variable streams need to identify and account for those hydrologic cycles (Larned and others 2010; Stanley and others 1997; Stromberg and others 2005). This suggests a need for cost-effective methods to repeatedly map wetted reaches in intermittent streams.

Standard methods for monitoring stream and groundwater conditions typically measure at a small set of geographic points (e.g., stream flow at gages, groundwater elevation at wells) at frequent time intervals. These provide precise measurements of conditions at a few locations, but require extensive interpolation to characterize basin-scale conditions, and do not effectively communicate the essential spatial relationships of complex hydrologic systems. In addition, developing long-term data sets requires significant financial and organizational investments to maintain equipment and data collection (e.g., each U.S. Geological Survey stream gage costs about $15,000/year to maintain). Aerial photographs have sometimes been used to determine extent of perennial flow, but their utility is impaired by riparian tree canopy which often obscures the view of a stream in places with perennial flow or shallow groundwater.

Wet/dry mapping, as we have applied it, uses citizen scientists to annually map the spatial extent of surface flow in a river. In contrast to most standard hydrologic monitoring methods, this approach measures conditions over a large, continuous geographic domain, but at relatively infrequent time intervals. The method provides a comprehensive snapshot of conditions for the whole river at the same date each year, allowing comparisons of year-to-year variability. Our use of wet/dry mapping described below has run for more than a decade, with little cost, and has provided useful data for water management, riparian studies, and protection of aquatic species. It has also engaged the local communities in understanding more about the status of the river.

The goals of this paper are to: (1) describe the technique of wet/dry mapping, and (2) provide an example of its application to the San Pedro River, Arizona.

Study Site

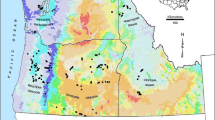

The San Pedro River flows 279 km (173 mi) north from its headwaters in northeastern Sonora, Mexico, to its confluence with the Gila River in southeastern Arizona, USA (Fig. 1). It is one of the few remaining free-flowing perennial streams in this semi-arid region, but has lost more than 50% of its perennial length (Brown and others 1981). The river’s riparian forest supports more than 350 bird species and has some of the highest reported breeding and migratory bird densities in North America (Skagen and others 1998; Krueper 2000). In 1988, the US Congress designated the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA), the first of its kind in the nation, to protect the riparian area and its aquatic resources.

Groundwater discharge supports the base flows in the river. Groundwater also supports the growing human population in the city of Sierra Vista and in rural Cochise County, Arizona. Wells in the Sierra Vista and Cananea subwatersheds (Fig. 1) remove water at 240% of the natural recharge rate, approximately 145,000 vs. 60,600 m3/day, causing a large and growing deficit in the water budget (Pool and Dickinson 2007). The continuous presence of surface flow in the river, along with the shallow groundwater that supports it, is a primary driver of riparian conditions and thus of wildlife habitat (Stromberg and others 2006). If historical trends continue, declines in groundwater levels due to pumping will eventually reduce base flow in the river and damage the riparian vegetation within the SPRNCA (Leenhouts and others 2006). A combination of water conservation, reuse, recharge, and augmentation projects in the Sierra Vista subwatershed implemented by the Upper San Pedro Partnership and its member agencies have restored about 32,000 m3/day toward the annual water budget in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed in 2007 (USGS 2008), but a deficit remains.

Stream flow levels at the Charleston gage (USGS station 09471000, Fig. 2) have traditionally been considered the lead metric for the San Pedro River’s upper basin, primarily due to the long period of record there. Summer base flow at the gage has declined over the past century, to the point of zero flow in July 2005 for the first time since it was established in 1903. This pattern is partly tied to declines in warm-season rainfall (Thomas and Pool 2006). About 55% of summer base flow at Charleston consists of recharged floodwaters from the previous warm season, a proportion that ranges up to 80% at Palominas (Baillie and others 2007, Fig. 2). While other causes of base flow decline have not been quantified, they likely include groundwater pumping from wells near the river and changes in riparian and upland vegetation (Leake and others 2008; Thomas and Pool 2006).

This map shows the San Pedro River and San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. The heavy river line shows reaches which were mapped as consistently wet in all 12 years surveyed. Bars on right side represent wet reaches for each year, 1999–2010. Labels on the far right identify the 10 analysis segments, each covering 8.06 km. The study area includes three stream gages, as shown: Palominas, Charleston, and Tombstone. Rainfall data reported here was from the town of Tombstone, not the Tombstone gage site

Precipitation in the upper San Pedro River basin ranges from 35 to 76 cm/year (14–30 in/year). It is predictably bimodal, with a summer monsoon season from July through September and a winter wet season December through March. Stream flow is lowest in April through June, typically reaching its low point in June.

Despite wet and dry periods, no long-term trend appears in the annual rainfall record for nearby Tombstone, AZ (Fig. 2), for the period 1913–2002 (MacNish and others 2009; Pool and Coes 1999; Thomas and Pool 2006). While year-to-year variation can have significant effects on water table elevation at the mountain fronts where most recharge occurs, those fluctuations are dampened as they move across the basin so the amount of groundwater reaching the river from the regional aquifer is fairly constant over time (MacNish and others 2009; Wahi and others 2008).

Methods

From 1999 through 2010, staff from The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) coordinated efforts of volunteers to map the spatial extent of wet reaches on the SPRNCA. The exact dates varied slightly, but mapping was conducted during the third weekend of June each year to coincide with the lowest flow before the expected start of the summer rainy season. For the first three years, mapping was conducted on the 80.6 km portion that lies within the SPRNCA, and only data from that portion are presented here. Beginning in 2002, progressively more of the river and its tributaries were surveyed, increasing to a high of 212 km in 2010, 76% of the total river length, from reaches within Mexico down to its confluence with the Gila River.

Surveyors were trained for consistency in data collection each year, during a social event that also incorporated sharing previous results, essential safety precautions, and logistics. Groups were assigned to predetermined portions of the river, ensuring continuous coverage along the river.

Surveyors recorded the beginning and end points of all surface water reaches ≥9.1 m (30 ft) in length, using paper data forms and consumer-grade global positioning system (GPS; Garmin 76) units that we provided. They also disregarded any dry gaps <9.1 m (30 ft) in otherwise wet reaches. While those short wet or dry reaches may have significant ecological meaning as refugia or barriers, this approach acknowledged the potential for cumulative location errors inherent in the GPS units (e.g., due to atmospheric distortions of the satellite signal), and simplified data collection in areas with short gaps or small pools. Most surveyors walked their portions, but some long dry portions were also surveyed on horses or all-terrain vehicles. The GPS units were collected and downloaded on the survey days and the data examined for obvious errors or omissions.

The resulting end-point coordinates were imported to a geographic information system (ArcGIS version 9, Environmental Systems Research Institute), and snapped to the closest points on a linear representation of the river (National Hydrography Dataset, 1:24,000-scale, US Geological Survey, http://nhd.usgs.gov), with manual corrections for errors caused by river bends. By using linear referencing, the wet reaches and overall surveyed reaches were converted to tables with start and stop points along the line. Because they share a common geometry, this allowed easy manipulation and analysis of the spatial data with common spreadsheet software and allowed direct comparison between years. Starting in 2007, maps and summary data from the wet/dry surveys have been posted each year to a web site (http://www.azconservation.org) for public distribution.

Data Analysis

To determine whether there have been localized changes over time, we divided our study area into 10 equal segments, 8.06 km long (Fig. 2). These analysis segments were identified post-hoc, without regard for surface flow or survey effort, and were intended to provide unbiased analysis units. Using program JMP version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) the wetted length within each segment across all years was examined for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test, and 7 segments showed significant variation from a normal distribution at α = 0.05. The Durbin-Watson test showed that a different set of 7 segments appear to have autocorrelation through time. Thus all segments were analyzed for trend with the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test (Kendall and Gibbons 1990), using a correction for one-year serial correlations within program Multitest version 5 (Grimvall, Libiseller, and Wahlin, Linköping University 2009). For graphic purposes, we calculated the Sen (1968) estimate of linear trend using program MAKESENS version 1.0 (Finnish Meteorological Institute).

The analysis segments were also compared to each other for variation in their response to regional weather conditions, using a null hypothesis that wetted length will vary in the same direction and proportion for all segments in a given year. Residual values were calculated by subtracting the mean for all segments in a given year from the value of each segment in that year. Pairwise comparisons between the residuals of segments were made with the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test using program JMP.

Results

Total wetted length of the San Pedro River through the SPRNCA varied from 35.8–57.3 km (mean = 42.8 km, +/− 1.79 km SE). Across 12 years of surveys, we found 62 separate reaches of various lengths that each had surface flow in all years, totaling 32% (25.6 km) of the river through the SPRNCA (Fig. 2). The length with surface flow in all years was less than in any given year, due to year-to-year variations. Total wetted length was positively correlated with the mean daily flow rate at the Charleston gage on the day of the survey (P = 0.001, R 2 = 0.68).

In all but two of the analysis segments, the wetted length varied year to year (Figs. 2, 3), but only Segments 2 and 5 showed a significant trend over time (Table 1). The reported trend in Segment 5 is not meaningful, as it describes a line of zero slope. The magnitude and direction of year-to-year variation differed between segments, aside from Segments 5 and 6 which were completely wetted in all but one year. In pairwise comparisons of residuals for all segments, we found significant variation between most pairs of segments. Only two sequential pairs of segments, 5–6 and 8–9, had similar year-to-year responses, as did four non-sequential pairs (Table 2).

Discussion

Wet/Dry Mapping as a Monitoring Technique

Wet/dry mapping is a simple concept for monitoring changes in surface water extent, and has been relatively straightforward to apply. Despite some turnover among organizers and participants, the methods have remained consistent for more than a decade, aside from minor refinements in the data forms and training. The resulting data have allowed both quantitative analysis and spatial representations of conditions.

Wet/dry mapping has provided several insights that were different from those offered by other monitoring techniques. The total wetted length within SPRNCA was correlated with stream flow at the Charleston gage, but those flow measurements could never describe the spatial arrangement of wet and dry stream channel, and wet/dry mapping provided no details on the rate of stream flow. Wet/dry mapping also showed that identification of perennial reaches depends critically on which years are examined.

Project costs included a one-time expense of $2,000 for 9 GPS units, along with annual costs of approximately five days of BLM and TNC staff time for training and survey events. Data processing and creation of display maps require about another seven days of staff time each year. Expansion of the project beyond the SPRNCA to the entire length of river in the US and Mexico has benefitted from efficiencies of scale, requiring very little increase in annual costs.

The Role of Citizen Science

The term “citizen science” has been used for projects in which volunteers, who may have no scientific training, collect data for research or monitoring projects directed by scientists. The approach has been used for a variety of efforts, including the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, which has run annually since 1900. Citizen scientists have worked on several other river conservation efforts in Arizona, including water quality sampling on the Santa Cruz and Verde Rivers. Such efforts often include social goals, such as education and public participation in politically-charged technical issues (Clark and Illman 2001). There is a growing need for tools to resolve conflicts associated with water management, and this type of participatory, citizen science may be helpful for basins where conflicting opinions exist in the absence of adequate streamflow data, or as a supplement to standard stream gages.

Citizen scientists have been critical to the wet/dry mapping project, and this volunteer approach had social and scientific benefits. This project engaged hundreds of volunteers in understanding and appreciating the flow variability in their local river. They included elected officials, military personnel, environmental activists, ranchers, business representatives, land managers, academics, and regulatory agency staff getting their feet wet and sharing an interest in the river’s life. As a result of their involvement, we have been able to create a useful data set with a small investment of time and money.

Implications for San Pedro River Management

Adaptive management toward the sustainable yield of groundwater in this region will require that monitoring programs, such as the wet/dry mapping effort, provide feedback on the effectiveness of a wide spectrum of management measures. Only by considering how surface flows are changing spatially, in a comprehensive manner, can we fully understand the combined effects of management efforts across the watershed.

As an example, the longest permanently wet reach, occurring in Segments 5 and 6, coincided with an area of shallow clay and near-surface bedrock (Fig. 2; Gettings and Houser 2000; Pool and Dickinson 2007). While continual base flows in these segments were documented in the earliest years of this project, they are also almost perfectly coincident with rising regional groundwater elevations from a City of Sierra Vista effluent recharge facility which began operations in 2002 (Schmerge and others 2009). While recharged effluent is likely augmenting the magnitude of base flows in that reach, no statistically-significant change in the spatial extent of flows is evident. Changes in the magnitude of flows are still best detected by conventional stream gage monitoring.

The increasing length of wetted channel in Segment 2, in contrast to other segments, suggests a localized change in groundwater availability. During the period of this study, conservation land purchases retired 114 ha of irrigated farm fields near or adjacent to the river in Segments 1 and 2, likely reducing water consumption in that vicinity (TNC unpublished data). Wet/dry mapping cannot prove causality for changes in baseflows within a complex hydrologic system. However, we do believe the method holds great promise for distinguishing system-wide influences on flows, such as climate change, from the localized influences of groundwater withdrawals or artificial recharge. These insights can be helpful for refining conservation strategies.

Results of the wet/dry mapping project have had several applications during the past decade. The organizing board of the Upper San Pedro water district included the 2008 wet/dry map in their comprehensive water resources plan (ADWR 2010). The USGS used wet/dry data to delineate study reaches for riparian community conditions (Leenhouts and others 2006). The BLM has used the data to better understand the distribution and effects of beaver activity on surface flows since their reintroduction, and academic researchers have used the data to help design various research and monitoring efforts (e.g., Stromberg and others 2006).

Implications for Ecological Research

Recent studies have noted that spatial intermittency in surface flow has large effects on ecological conditions within aquatic and riparian systems (Boulton and Lake 2008; Larned and others 2010; Stanley and others 1997; Stromberg and others 2005). Repeated measurements in a few systems have shown complex longitudinal patterns in flow permanence (the proportion of time that water is present) leading to identification of long-term average flow permanence as a driver of community structure in intermittent streams (see review by Larned and others 2010). One measure of this has been the percentage of time with surface flow at a site in a given year (Stromberg and others 2005).

This study shows that flow permanence during a predictably dry season can vary across time as well as space in a groundwater-fed, main stem river. While some reaches of various lengths were consistently wet and thus perennial, total wetted length varied widely from year to year within most analysis segments and across the study area as a whole. Thus, using a single-year assessment of flow status may give an inaccurate basis for analyzing the ecological community in a spatially-intermittent stream. It also suggests the need to test whether average flow permanence or a percentage of days with flow is the best metric for the ecological effects of intermittent flow, or if some minimum value has greater explanatory value.

Other Applications of the Wet/Dry Mapping Technique

This approach has been used in other stream systems around Arizona, including Cienega Creek (conducted by TNC, BLM, and Pima County), Agua Fria River (Arizona NEMO), and several tributaries of the San Pedro (TNC).

Wet/dry mapping to monitor seasonal changes in flow length and groundwater conditions on part of Cienega Creek have been conducted by the Pima Association of Governments since 1999 (Fonseca 2008). Surface flow was mapped for ten years prior to that by a consultant using aerial surveys, but they changed to walking surveys after the riparian forest canopy closed over perennial reaches. Pima County has also used their wet/dry data to identify discharge cells for MODFLOW hydrologic models, and to justify an instream flow water right application by documenting the extent of perennial flow (J. Fonseca, personal communication).

Conclusion

Wet/dry mapping on the San Pedro River has brought many benefits, and the results have had many uses. The finding that roughly half of the river’s length continues to flow all year has changed many people’s perception of the river. Before wet/dry data were available, some believed the river had already disappeared and that “saving” it was a lost cause, while others swore it flowed almost continuously over its entire length and that water management actions were needless. We now know that the truth lies somewhere in the middle of these perceptions, and that the difference in outcomes between these extremes will likely depend on decisions made in the near future. The role of collaborative learning processes in effectively transforming science into informed decisions will continue as one of the essential factors that determine the fate of this river and of the waters that sustain it (Richter and others 2009). Surface flow has declined relative to historic records, but a significant portion of the river still exhibits perennial flows, a rarity for Arizona and the desert Southwest. Is the San Pedro’s glass half empty or half full? That will only be answered with certainty as adaptive management efforts apply new strategies to ensure the river’s flows into the future.

References

Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) (2010) Upper San Pedro Water District comprehensive water resources plan. pp. 17

Baillie MN, Hogan JF, Ekwurzel B, Wahi AK, Eastoe CJ (2007) Quantifying water sources to a semiarid riparian ecosystem San Pedro River Arizona. Journal of Geophysical Research 112:GO3S02

Boulton AJ, Lake PS (2008) Effects of drought on stream insects and its ecological consequences. In: Lancaster J, Briers RA (eds) Aquatic insects: challenges to populations. CABI International, Wallingford, pp 91–102

Brown DE, Carmony NB, Turner RM (1981) Drainage map of Arizona showing perennial streams and some important wetlands. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix. 1 sheet (1:1,000,000)

Clark F, Illman DL (2001) Dimensions of civic science: introductory essay. Science Communication 23:5–27

FitzHugh TW, Richter BD (2004) Quenching urban thirst: growing cities and their impacts on freshwater ecosystems. Bioscience 54:741–754

Fonseca J (2008) Aquifer monitoring for groundwater-dependent ecosystems, Pima County, Arizona. Pima County Natural Resources, Parks and Recreation, Tucson, p 36

Gettings ME, Houser BB (2000) Depth to bedrock in the Upper San Pedro Valley, Cochise County, southeastern Arizona. Open-File Report 00–138, online version 1.0. US Geological Survey, Tucson

Humphries P, Baldwin DS (2003) Drought and aquatic ecosystems: an introduction. Freshwater Biology 48:1141–1146

Kendall MG, Gibbons JD (1990) Rank correlation methods, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, p 260

Krueper DJ (2000) Annotated checklist to the birds of the Upper San Pedro River Valley, Arizona. US Bureau of Land Management, Tucson

Larned ST, Thibault D, Arscott DB, Tockner K (2010) Emerging concepts in temporary-river ecology. Freshwater Biology 55:717–738

Leake SA, Pool DR, Leenhouts JM (2008) Simulated effects of ground-water withdrawals and artificial recharge on discharge to streams, springs, and riparian vegetation in the Sierra Vista Subwatershed of the Upper San Pedro Basin, southeastern Arizona. US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5207, p 14

Leenhouts JM, Stromberg JC, Scott RL (eds) (2006) Hydrologic requirements of and consumptive ground-water use by riparian vegetation along the San Pedro River, Arizona. US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5163, p 154

MacNish R, Baird KJ, Maddock T III (2009) Groundwater hydrology of the San Pedro River Basin. In: Stromberg JC, Tellman B (eds) Ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 285–299

Pool DR, Coes AL (1999) Hydrogeologic investigations of the Sierra Vista sub-watershed of the upper San Pedro Basin, Cochise County, southeast Arizona. US Geological Survey Water Resources Investigations Report 99-4197, p 41

Pool DR, Dickinson JE (2007) Ground-water flow model of the Sierra Vista subwatershed and Sonoran portions of the upper San Pedro basin, southeastern Arizona, United States, and northern Sonora, Mexico. Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5228, p 48

Postel S (2000) Entering an era of water scarcity: the challenges ahead. Ecological Applications 10:941–948

Richter H, Goodrich DC, Browning-Aiken A, Varady R (2009) Integrating science and policy for water management. In: Stromberg JC, Tellman B (eds) Ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 388–406

Schmerge D, Corkhill F, Flora S (2009) Water level conditions in the upper San Pedro basin, Arizona, 2006. Water level change map series report #3. Arizona Department of Water Resources, Phoenix

Sen PK (1968) Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. Journal of the American Statistical Association 63:1379–1389

Skagen SK, Melcher CP, Howe WH, Knopf FL (1998) Comparative use of riparian corridors and oases by migrating birds in southeast Arizona. Conservation Biology 12:896–909

Sponseller RA, Grimm NB, Boulton AJ, Sabo JL (2010) Responses of macroinvertebrate communities to long-term flow variability in a Sonoran Desert stream. Global Change Biology 16:2891–2900

Stanley EH, Fisher SG, Grimm NB (1997) Ecosystem expansion and contraction in streams. BioScience 47:427–435

Stromberg J, Briggs M, Gourley C, Scott M, Shafroth P, Stevens L (2004) Human alterations of riparian ecosystems. In: Baker M Jr, Folliott P, DeBano L, Neary DG (eds) Riparian areas of the southwestern United States: hydrology, ecology, and management. Lewis Publishers (CRC Press), Boca Raton, pp 101–126

Stromberg JC, Bagsted KJ, Leenhouts JM, Lite SJ, Making E (2005) Effects of stream flow intermittency on riparian vegetation of a semiarid region river (San Pedro River, Arizona). River Research and Applications 21:925–938

Stromberg JC, Lite SJ, Rychener TJ, Levick LR, Dixon MD, Watts JM (2006) Status of the riparian ecosystem in the Upper San Pedro River, Arizona: application of an assessment model. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 115:145–173

Thomas BE, Pool DR (2006) Trends in streamflow of the San Pedro River, southeastern Arizona, and regional trends in precipitation and streamflow in southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. US Geological Survey Professional Paper 1712, p 79

US Geological Survey (USGS) (2008) Water management of the regional aquifer in the Sierra Vista subwatershed, Arizona, 2007 report to Congress. p 80

Wahi AK, Hogan JF, Ekwurzel B, Baillie MN, Eastoe CJ (2008) Geochemical quantification of semiarid mountain recharge. Ground Water 46:414–425

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed substantial effort to organizing and conducting the wet/dry surveys and to mapping the data, especially Bill Childress, Nate Dieterich, Mark Rekshynskyj, Sandy Kunzer, Betsy Kunzer, Matt Killeen, Michael List, Dan Majka, and staff of the BLM Gila District Office. We also recognize the hundreds of committed American and Mexican volunteers over the past decade who got their feet wet and grew this project to encompass 120 miles of the San Pedro River. The manuscript was improved by suggestions from Julia Fonseca, Jeanmarie Haney, Peter Karieva, Lainie Levick, Marcos Robles, John Sanderson, Stacie Solie, Ellen Wohl, and 3 anonymous reviewers. Financial support was provided by Friends of the San Pedro, the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust, Arizona NEMO, and the Walton Family Foundation. In-kind support was provided by the Bureau of Land Management, Community Watershed Alliance, Cascabel Volunteers, Salt River Project, CONANP, BIDA, Reserva Forestal National y Refugio de Fauna Silvestre Ajos-Bavispe, Naturalia, and The Nature Conservancy.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, D.S., Richter, H.E. Wet/Dry Mapping: Using Citizen Scientists to Monitor the Extent of Perennial Surface Flow in Dryland Regions. Environmental Management 47, 497–505 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9607-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9607-y