Abstract

Past studies have revealed the benefits of rodent participation in the colonization process of oak species. Certain rodent species (Apodemus sylvaticus and Mus spretus) partially consume acorns, beginning at the basal part and preserving the embryo. Perea et al. (2011) and Yang and Yi (2012) found that during periods of abundance, the remains left after partial consumption continue to be present on the surface and are not transported to caches, given that they are perceived as leftovers. These remains, produced after several visits by the cache owner or by thieving conspecifics, also appear in the caches. If they are perceived as offal, they will not be attacked and may remain in these stores for longer periods, serving as resources for the cache builder. Our objective is to determine whether these remnants are perceived as offal by the rodent generating them or if the remains left by other rodents are considered offal. This is relevant in cases of theft, a common behavior of this species, if the thieving animals reject the remains. The results suggest that foreign remains and the rodents’ own remains are not rejected, but rather, they are consumed in preference to intact acorns. The intact acorns remain in the cache for longer periods and have a greater opportunity to germinate and emerge. Rodents prefer to consume foreign remains first. This may be due to the fact that, in case of shortage, it is considered advantageous to finish the reserves of a potential competitor before depleting one’s own reserves.

Significance statement

Rodents participate in the acorn dissemination process by constructing surface stores (caches). The rodent species studied here partially consumes acorns, beginning with the basal part and preserving the embryo located at the apical end. These partially consumed acorn remains are considered offal and remain in the caches for longer periods, serving as reserves for the rodent. Our objective is to examine whether these acorn remains are viewed as offal by the rodents. We have found that, to the contrary, they are consumed before intact acorns. Intact acorns remain in the caches for longer periods, assuming the role of reserves and taking on a greater capacity to germinate. This species of rodent differentiates between its own remains and those of others, first consuming the foreign offal. Therefore, their own offal remains in the stores for longer periods and may potentially germinate if the embryo is preserved. This behavior has been demonstrated by this rodent species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In previous studies, authors demonstrated the benefits of rodent participation in the colonization process of oak species (Morán-López et al. 2016; Gallego et al. 2017; Wang and Corlett 2017; Del Arco et al. 2018). Some authors have revealed that certain rodent species (Apodemus sylvaticus and Mus spretus) partially consume acorns, based on the ratio between the mass of acorns and the animal’s body mass (Muñoz and Bonal 2008), beginning at the basal part and preserving the embryo (Perea et al. 2011; Del Arco et al. 2018; Del Arco and Del Arco 2022), in both surface and scatter hoard caches (Del Arco and Carretero 2013; Zhang et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2016; Mittelman et al. 2021). Embryo preservation enhances the mutualistic relationship between the plant and the rodent (Muñoz and Bonal 2008; Del Arco et al. 2018; Bogdziewicz et al. 2020; Moore and Dittel 2020; Del Arco and Del Arco 2022).

Perea et al. (2011) and Yang and Yi (2012) found that during periods of abundance, the remains produced after partial consumption are left on the surface without being transported to the scatter hoard, where they would be buried (Perea et al. 2016; Dittel et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2017; Dittel and Vander Wall 2018; Li et al. 2018; Yi et al. 2019). Transporting these remains is not considered worthwhile. These acorns are left on the ground because competitors perceive them as leftovers (Perea et al. 2011). There is a lack of interest in the uneaten remains due to their perception as offal, undesired waste, because they lose turgidity upon dying, potentially altering their nutritional composition, with a possible resulting bad taste. If taken to the buried caches, the moisture of the remains would increase and they could potentially germinate and shell (Perea et al. 2011; Yang and Yi 2012). The caches contain remains of partially consumed acorns resulting from successive visits by cache owners or thieving rodents to feed (Muñoz and Bonal 2011; Yi et al. 2016; Yang and Yi 2018).

The M. spretus species displays these behaviors. These rodents partially consume acorns, starting at the basal end and maintaining the embryo. They build hoards that they visit repeatedly to stock up on food (Bartlow et al. 2018), while pilfering from other rodents’ hoards encountered during the foraging period (Wang et al. 2017, 2018, 2019).

The following questions arise in response to these behaviors: Are partially consumed acorn remains in fact perceived as offal by this rodent species and subsequently rejected? Can this species differentiate between its own remains and remains generated by a distinct congener? Which does it prefer? The consequences of the oak seed dispersal process are clear. If the remains are rejected by the owner of the cache or by the rodent acting as a thief, they will remain in the cache for a longer period, and because the embryo is preserved, they will germinate.

To respond to these questions, we designed three experiments. In the first and the second experiments, we attempted to determine if the rodents’ own remains (experiment 1) or foreign remains (experiment 2) were rejected. In the third experiment, we examined whether this species differentiates between remains and which it prefers, its own or those of others.

Once the results of these three experiments were obtained, another doubt arose. The remains used in the three experiments were between 1 and 3 days old, but we found that remains that had an age of up to 1 week were covered with fungi and mold on the open cotyledons. This led to the following question: Does the presence of mold change the organoleptic characteristics of the remains and alter the preferences observed in the three previous experiments? To test this, we repeated experiments 1 and 2, but using 1-week-old remains containing mold. These are the fourth and fifth experiments.

The presence of each of these types of acorns in the caches and the time remaining in storage condition the success of the oak dispersal process.

Methods

Study system

For this study, we captured 15 Mus spretus Lataste, 1883 (Algerian mouse) specimens. They were placed in a 100 m2 fenced enclosure. Inside this enclosure, 16 plots measuring 4 m2 (2*2 m per side) were built. Each of these plots was isolated using a 2 m wide metal sheet buried in the ground at a depth of 50 cm and a height of 1 m on all sides of the square to prevent the rodents from escaping by jumping. Under these conditions, the mice behaved as if they were in semi-wild conditions: building burrows, creating shallow storages, galleries, pantries, and caches to hide the acorns, which they moved around the plot.

Experimental procedures and design

The rodents were fed with acorns from the Quercus ilex subsp. (Desf.) Samp. (Holm oak). This plant species dominates in distribution and abundance in the study area, making it likely that this rodent species has fed on these acorns since ancient times. The acorns were collected in the environment where the mice were captured. All of the acorns selected for the study were marked with a small and numbered plastic tag that was attached by a thin wire placed in the middle of the acorns (Fig. 1). They were all weighed with their label and wire prior to being placed in the plot. This is a nocturnal rodent species. All acorns, remains or intact, that remained after each night of breeding were removed in the early morning hours after searching the plot for the remnants of the nocturnal transport. This species engages in the partial consumption of most of the acorns, starting at the basal end and keeping the embryo at the apical end until the acorn is completely consumed (Fig. 1). All acorn remains were reweighed with their label and wire to estimate the mass consumed per acorn during the night. They were then quickly returned to the plot in their initial position to prevent odor loss due to handling. This handling was performed using sterilized paints and gloves to avoid altering any odor marks that the rodent may have left on the acorns with their urine or defecation during the previous night (Sunyer et al. 2013). On days prior to the start of each experiment, we provided each mouse with a large number of weighed and labeled acorns. The objective was to have several partially consumed acorns from each rodent in order to consider these remains their own offal. Some of these partially consumed acorn remains were kept for a week in small cages, inaccessible to the mouse, situated in the plots of each rodent. During this period, the remains suffered a natural deterioration and became covered with mold as occurs in acorns processed by these rodents in the wild. In each experiment, the acorns were offered in a pile that was placed in an area of the plot that was covered superficially by earth, stones, leaf litter, or dry grasses, imitating the caches made by this species in the wild.

To respond to these questions, we designed five experiments (Fig. 2). The first three refer to the questions that initially prompted this study: Are the remains perceived as offal? Do the rodents distinguish between their own remains and those of others? The last two experiments, the fourth and fifth, were designed upon finding that the age of the remains could change the organoleptic characteristics of the same, potentially influencing consumption preferences. These experiments refer to the following questions: Are remains containing mold rejected? To conduct the experiments, we used five types of acorns: intact (I), 1–3-day-old own remains (PI), 1–3-day-old foreign remains (PO), 1-week-old own remains (PIM), and 1-week-old foreign remains (POM) (Fig. 2).

First experiment

In the first experiment we attempted to answer the question: Are the rodents’ own remains perceived as offal? Are the rodents’ own remains rejected?

In response to these questions, we examined the rodents’ preference for their own remains as compared to the intact acorns. We gave the 15 rodents five intact acorns (I), and five of their own 1–3-day-old remains (PI) every day for 10 days (Fig. 3). A total of 1500 acorns were used during the experiment. We estimated these preferences as a function of the number of acorns attacked in each group, as a function of the total mass consumed each day within each group, and as a function of the mean mass consumed per acorn or remainder each day within the two groups. These same three means of estimating preferences were applied in the five experiments.

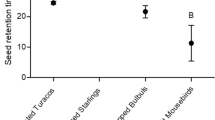

Acorn categories consumed by M. spretus in a experiment 1 (I, intact; PI, own remains 1–3 days old); b experiment 2 (I, intact; PO, foreign remains 1–3 days old); c experiment 3 (PI, own remains 1–3 days old; PO, foreign remains 1–3 days old). Number of acorns/day; total mass/day (g); mean mass/acorn day (g), each mouse per day, 15 mice, 10 days

Second experiment

The second experiment was designed to respond to the questions: Are foreign remains perceived as offal? Are they rejected and not attacked? Like the previous one, this experiment lasted 10 days and the same 15 mice were used. Each day, the mice were provided with five intact acorns (I) and five 1–3-day-old remains (PO) generated by another congener (Fig. 3). We examined the preferences for intact acorns or foreign remains, as a function of the number of acorns attacked in each group, as a function of the total mass consumed each day within each group, and as a function of the mean mass consumed per acorn or remains each day within the two groups.

Third experiment

The third experiment was designed in response to the question: “Which remains does this rodent species prefer, its own or those of others? During the 10 days of the experiment, we provided each of the 15 mice with five remains generated by the mouse (PI) and five remains generated by another rodent (PO) (Fig. 3). In both cases, the remains were generated during the previous three days. We examined the preferences according to the number of remains of each group attacked by each mouse each day, the total mass consumed per day in each group, and the mean mass consumed per acorn each day.

Given that it was verified that the remains deteriorate over time, with the cotyledons exposed to the air becoming covered with fungi and molds, the following question arose: Can these modifications due to the age of the remains affect the preferences of this rodent species seen in the previous experiments? To consider this, we repeated experiments 1 and 2 by replacing the 3-day-old remains with 1-week-old offal.

Fourth experiment

In this experiment, a repetition of the first one, we asked, are the remains rejected due to the presence of mold? This experiment also lasted 10 days and the same 15 mice were used (Fig. 4). Each day, they were provided with five intact acorns (I) and five 1-week-old remains with molds (PIM) generated by the mouse. We used the variables number, total daily mass, and mean mass consumed per acorn to estimate the preferences for the two groups of acorns provided.

Fifth experiment

In the fifth experiment, a repetition of the second, we asked the same question as previously, although in this case, with foreign remains: Are foreign remains rejected due to the presence of mold? This experiment also lasted 10 days and the same 15 mice were used. Each day, the mice were provided with five intact acorns (I) and five 1-week-old remains with molds (POM) generated by another congener (Fig. 4). We used the number of acorns attacked per rodent per day, the total daily mass consumed by each mouse, and the mean mass consumed per acorn per day to estimate preferences for the two groups of acorns provided.

Data analysis

The possible effects of acorn category consumption (intact acorns (I), acorns that were partially consumed by the mice (PI), those partially consumed by a conspecific (PO)), day (10 levels), and interactions with the number of acorns eaten per specimen, total acorns mass per day, and mean acorns mass per day, were analyzed using linear mixed models (LMM) with the restricted maximum likelihood method (REML). The specimens were treated as the random factor and time was the repeated factor. Finally, working with the model matrix, contrasts were performed to examine the differences between fixed factor levels (Pinheiro and Bates 2000). The Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for the significance level of each t-test (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). Statistical calculations were performed in the R software environment (version 2.15.3; R Core Team 2013), using the NLME package for LMM (Pinheiro et al. 2013).

Blinded methods were used for the recording and analysis of all behavioral data, to minimize observer bias.

Results

In the first experiment, we examined the preferences of the Algerian mouse for intact acorns (I) or for remains generated by the rodent itself (PI). The LMM indicates that, for the three variables measured, significant differences exist between the two groups (Table 1). The number of acorns consumed each day by each mouse was higher in the remains group (PI) than in the intact acorn group (I) (Fig. 1a). The total daily mass of acorns consumed was also higher in the remains group (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the mean mass consumed per acorn was higher in the remains group than in the group of intact acorns (Fig. 1a).

No significant differences in time were found between the two groups of acorns for any of the three variables used (Table 1). Therefore, neither the number of acorns attacked, the daily mass consumed, nor the average mass per acorn changed over the days of the experiment.

As a result of the second experiment in which we compared the preferences of the Algerian mouse for intact acorns (I) or remains generated by another congeneric rodent (PO), according to the LMM, it was found that significant differences exist between both acorn groups (Table 2). Specifically, the number of acorns consumed daily by each mouse is higher in the foreign remains (PO) group than in the intact acorn (I) group (Fig. 1b). The same is true for the total mass of acorns consumed per day and the mean mass per acorn consumed daily (Fig. 1b). In both cases, they are higher in the foreign remains (PO) group than in the intact acorn (I) group. Time does not significantly affect the three variables (Table 2).

In the third experiment, we tested the preferences of the Algerian mouse for its own remains (PI) and foreign remains (PO). The results reveal significant differences between both acorn groups (Table 2). The number of acorns attacked daily by each mouse is higher in the foreign remains group (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the total mass consumed daily is higher in these foreign remains (PO) group than in the own remains (PI) group (Fig. 1c). Likewise, the mean mass per acorn consumed daily is higher in the foreign remains group (Fig. 1c). Time is not found to significantly affect the three variables studied (number, total daily mass, and mean mass consumed per acorn per day). None of them changed during the experiment (Table 3).

In the fourth experiment, like the first one, we studied the preferences of the Algerian mouse for intact acorns (I) or acorn remains generated by the rodent participating in the test (PIM), but unlike the first experiment, the remains were 1 week old. They were generated by the same mouse, but 1 week previously. The open part of the cotyledons contained mold (PIM). The LMM indicates that significant differences exist between the two acorn groups (Table 4). The number of acorns attacked daily by each mouse is higher in the group of acorn remains containing mold (PIM) than in the intact acorn (I) group (Fig. 2a). The total mass of acorns consumed daily is also higher in the own remains group than in the intact acorn group (Fig. 2a). The same is also true for the mean mass consumed per acorn daily (Fig. 2a). Time did not alter the values of these three variables during the experiment (Table 4).

The results of the fifth experiment are similar to those obtained in the second experiment. The preferences examined here were intact acorns (I) versus remains generated by a congener, but 1 week previously (POM). These remains were moldy. As in the previous experiments, according to the LMM, the differences observed in each group are significant (Table 5). The number of acorns attacked daily by each mouse is higher in the group with moldy remains (POM) than in the intact acorn (I) group (Fig. 2b). The total mass consumed daily is higher in the foreign remains covered with mold (Fig. 2b). The mean mass consumed per acorn daily is higher in the foreign remains (POM) than in the intact acorns (I) (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Perea et al. (2011) and Yang and Yi (2012) proposed that partially consumed acorns were abandoned on the surface because these remains were perceived by rodents as offal. Our results indicate that, to the contrary, the remains of partially consumed acorns are not perceived as offal and are not discarded; in fact, they are even more highly appreciated than intact acorns. Foreign remains and those generated by the mouse itself are consumed before the intact acorns, as found in experiments 2 and 1, respectively, and even when the foreign and own remains are covered by a layer of mold on the exposed cotyledons, as seen in experiments 4 and 5, respectively. What is the reason for this preference? We believe that this preference may be energy-related, given that less energy expenditure is required (Sundaram et al. 2015). Removing the shell from acorns implies a high energy expense in addition to being subject to an unpleasant taste due to the presence of tannins (Steele et al. 1993; Perea et al. 2011; Muñoz et al. 2012). Accessing remains with an already removed shell is easier and requires less energy (Jansen et al. 2010; Yi et al. 2012). Shelling acorns is energy-intensive, so shelled acorns are preferred, even if a layer of mold needs to be removed to access the cotyledons. It is likely that the mold modifies the palatability of acorns, but nevertheless, it is more profitable to consume shelled acorns than to expend energy to remove the shell (Perea et al. 2011; Muñoz et al. 2012).

The consequences in terms of acorn dissemination are that intact acorns may remain in the scatter hoards for longer periods of time, thus having a higher likelihood of germinating and shelling (Yang and Yi 2012).

Rodents of this species can distinguish their own acorn remains from those of others. We have observed that they prefer foreign remains to their own (experiment 3). This behavior may be motivated by the fact that, in case of acorn scarcity, it may be convenient to preserve one’s own remains and prematurely consume the remains of others found in scatter hoards (Steele et al. 2011; Alpern et al. 2012; Lichti et al. 2015; Dittel et al. 2017; Dittel and Vander Wall 2018). The implication for the seed dispersal process is that the remains are in the scatter hoards for longer periods of time. Since this rodent species engages in partial consumption of acorns and preserves the embryo (Del Arco et al. 2018; Del Arco and Del Arco 2022), these acorn remains may have the opportunity to germinate and emerge as intact acorns since the embryo remains viable, even though part of the cotyledons is missing. Perea et al. (2012) considered that plants place more resources in the cotyledons than necessary for the acorn to germinate and settle. Therefore, fewer cotyledons may still provide the necessary resources to germinate with depleted cotyledons (Yang and Yi 2012).

These remains are consumed in the scatter hoards first, allowing the intact acorns to remain in these stores for longer periods, giving them the opportunity to germinate and shell (Yang and Yi 2012). The own remains would play this same role since the foreign remains are consumed first, but only if the embryo is preserved. This is the behavior of this rodent species, which consumes acorns while preserving the embryo (Del Arco et al. 2018; Del Arco and Del Arco 2022).

Conclusion

Rodents of the species M. spretus do not perceive their own or foreign acorn remains found in caches as offal. Therefore, they do not remain in the caches for longer periods of time, and they do not serve as a reserve for the cache owner. This role is performed by the intact acorns, which remain in the caches for longer periods, given that the rodents’ own or foreign acorn remains are consumed first. Therefore, intact acorns have a higher likelihood of germinating. This rodent species differentiates between its own remains and those of foreign species, consuming the foreign ones first, allowing the own remains to stay in the caches for longer periods and having the opportunity to germinate if the embryo is preserved, a behavior displayed by this rodent species.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the [https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/57210] repository. All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Alpern S, Fokkink R, Lidbetter T, Clayton NS (2012) A search game model of the scatter hoarder’s problem. J R Soc Interface 9:869–879. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2011.0581

Bartlow AW, Lichti NI, Curtis R, Swihart RK, Steele MA (2018) Re-caching of acorns by rodents: cache management in eastern deciduous forests of North America. Act Oecol 92:117–122

Bogdziewicz M, Crone EE, Zwolak R (2020) Do benefits of seed dispersal and caching by scatterhoarders outweigh the costs of predation? An example with oaks and yellow-necked mice. J Ecol 108:1009–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13307

Del Arco JM, Carretero M (2013) Preferencias en el consumo de bellotas por Mus spretus Lataste (1883) y su influencia en la dispersión de especies quercíneas (preferences in the consumption of acorns by Mus spretus Lataste (1883) and their influence on the dispersion of oaks species). In: Martínez C, Lario FJ, Fernández B (eds) Advances in the restoration of forest systems: implantation techniques. SECF AEET, Palencia, Spain, pp 95–100

Del Arco JM, Beltrán D, Martínez-Ruiz C (2018) Risk for the natural regeneration of Quercus species due to the expansion of rodent species (Microtus arvalis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72:160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2575-6

Del Arco JM, Del Arco S (2022) Partial consumption of acorns by some rodents leads their relationship with oaks species towards mutualism. Ecol Evol Biol 7:1–6. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.eeb.20220701.11

Dittel JW, Vander Wall SB (2018) Effects of rodent abundance and richness on cache pilfering. Integr Zool 13:331–338

Dittel JW, Perea R, Vander Wall SB (2017) Reciprocal pilfering in a seed-caching rodent community: implications for species coexistence. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 71:147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-017-2375-4

Gallego D, Morán-López T, Torre I, Navarro-Castilla A, Barja I, Díaz M (2017) Context dependence of acorn handling by the Algerian mouse (Mus spretus). Act Oecol 84:1–7

Jansen PA, Elschot K, Verkerk PJ, Wright SJ (2010) Seed predation and defleshing in the agouti-dispersed palm Astrocaryum standleyanum. J Trop Ecol 26:473–480. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467410000337

Li Y, Zhang D, Zhang H, Wang Z, Yi X (2018) Scatter-hoarding animal places more memory on caches with weak odor. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72:53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2474-x

Lichti NI, Steele MA, Swihart RK (2015) Seed fate and decision-making processes in scatter-hoarding rodents. Biol Rev 92:474–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv12240

Mittelman P, Pires AS, Fernandez FAS (2021) The intermediate dispersal hypothesis: seed dispersal is maximized in areas with intermediate usage by hoarders. Plant Ecol 222:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-020-01100-6

Moore CM, Dittel JW (2020) On mutualism, models, and masting: the effects of seed-dispersing animals on the plants they disperse. J Ecol 108:1775–1783

Morán-López T, Wiegand T, Morales JM, Valladares F, Díaz M (2016) Predicting forest management effects on oak–rodent mutualisms. Oikos 125:1445–1457. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik02884

Muñoz A, Bonal R (2008) Are you strong enough to carry that seed? Seed size/body size ratios influence seed choices by rodents. Anim Behav 76:709–715

Muñoz A, Bonal R (2011) Linking seed dispersal to cache protection strategies. J Ecol 99:1016–1025

Muñoz A, Bonal R, Espelta JM (2012) Responses of a scatter-hoarding rodent to seed morphology: links between seed choices and seed variability. Anim Behav 84:1435–1442

Perea R, San Miguel A, Gil L (2011) Leftovers in seed dispersal: ecological implications of partial seed consumption for oak regeneration. J Ecol 99:194–201

Perea R, San Miguel A, Martínez-Jauregui M, Valbuena-Carabaña M, Gil L (2012) Effects of seed quality and seed location on the removal of acorns and beechnuts. Eur J for Res 131:623–631

Perea R, Dirzo R, San Miguel A, Gil L (2016) Post-dispersal seed recovery by animals: is it a plant- or an animal-driven process? Oikos 125:1203–1210. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik02556

Pinheiro J, Bates D (2000) Mixed-effects models in S and S-Plus. Springer, New York

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, The R Development Core Team (2013) nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Package Version 3:1–108. https://svn.r-project.org/R-packages/trunk/nlme/. Accessed 2023-08-09

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org. Accessed 2023-08-09

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1995) Biometry, 3rd edn. WH Freeman and Co, New York

Steele MA, Knowles T, Bridle K, Simms EL (1993) Tannins and partial consumption of acorns: implications for dispersal of oaks by seed predators. Am Midl Nat 130:229–238

Steele MA, Bugdal M, Yuan A, Bartlow A, Buzalewski J, Lichti N, Swihart R (2011) Cache placement, pilfering, and a recovery advantage in a seed-dispersing rodent: could predation of scatter hoarders contribute to seedling establishment? Act Oecol 37:554–560

Sundaram M, Willoughby JR, Lichti NI, Steele MA, Swihart RK (2015) Segregating the effects of seed traits and common ancestry of hardwood trees on Eastern gray squirrel foraging decisions. PLoS ONE 10:e0130942. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130942

Sunyer P, Muñoz A, Bonal R, Espelta JM (2013) The ecology of seed dispersal by small rodents: a role for predator and conspecific scents. Funct Ecol 27:1313–1321

Wang B, Corlett RT (2017) Scatter-hoarding rodents select different caching habitats for seeds with different traits. Ecosphere 8:e01774. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1774

Wang Z, Zhang D, Liang S, Li J, Zhang Y, Yi X (2017) Scatter-hoarding behavior in Siberian chipmunks (Tamias sibiricus): an examination of four hypotheses. Acta Ecol Sin 37:173–179

Wang Z, Wang B, Yi X, Yan C, Cao L, Zhang Z (2018) Scatter-hoarding rodents are better pilferers than larder-hoarders. Anim Behav 141:151–159

Wang Z, Wang B, Yi X, Yan C, Zhang Z, Cao L (2019) Re-caching behaviour of rodents improves seed dispersal effectiveness: evidence from seedling establishment. Forest Ecol Manag 444:207–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.044

Yang Y, Yi X (2012) Partial acorn consumption by small rodents: implication for regeneration of white oak, Quercus mongolica. Plant Ecol 213:197–205

Yang Y, Yi X (2018) Scatter-hoarders move pilfered seeds into their burrows. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72:158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2578-3

Yi X, Steele MA, Zhang Z (2012) Acorn pericarp removal as a cache management strategy of the Siberian chipmunk, Tamias sibiricus. Ethology 118:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j1439-0310201101989x

Yi X, Wang Z, Zhang H, Zhang Z (2016) Weak olfaction increases seed scatter-hoarding by Siberian chipmunks: implication in shaping plant–animal interactions. Oikos 125:1712–1718. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03297

Yi Y, Ju M, Yang Y, Zhang M (2019) Scatter-hoarding and cache pilfering of rodents in response to seed abundance. Ethology 125:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.12874

Zhang H, Steele MA, Zhang Z, Wang W, Wang Y (2014) Rapid sequestration and recaching by a scatter-hoarding rodent (Sciurotamias davidianus). J Mammal 95:480–490

Zhang D, Li J, Wang Z, Yi X (2016) Visual landmark-directed scatter-hoarding of Siberian chipmunks Tamias sibiricus. Integr Zool 11:175–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-487712171

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Junta de Castilla y León for granting permission to conduct this research; in their mission to safeguard ethics in animal welfare during their handling. We offer our thanks to Ángel José Álvarez Barcia, the director of S.I.B.A. (Servicio de Investigación y Bienestar Animal) at the University of Valladolid, for his advice on the proper treating and handling of rodents. We also wish to thank the associate editor, Prof. Erkki Korpimäki, and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments to improve the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This study was partially supported by the VA002A07 and VA035G18 projects granted by the Junta de Castilla y León to JMDA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures involving animals in this study were carried out according to the ethical standards of the institution where the studies were conducted (CEEBA University of Valladolid, Spain). The experimental procedures used were designed in accordance with the requirements of replacement, reduction, and refinement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by A. G Ophir.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Del Arco, S., Del Arco, J.M. The role of partially consumed acorn remains in scatter hoards and their implications in oak colonization. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 77, 132 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-023-03409-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-023-03409-4