Abstract

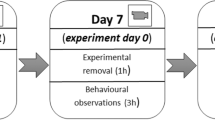

Parental care, a component of reproductive effort, should evolve in response to its impact on both offspring and parent fitness. If so, manipulations in brood value should shift levels of care in predictable ways, provided that appropriate cues about the change in offspring value are altered. Prior brood size manipulations in birds have produced considerable variation in responses that have not been fully investigated. We conducted paired, short-term (2 h) reductions and enlargements in brood size (± 2 nestlings) of house sparrows in each of 4 years. Parents at reduced broods shifted parental care downward in all four seasons. Parents experiencing increased broods responded significantly variably across years; in some, they increased care, but in others, they decreased care compared with control periods. Nestlings in both treatments gained less mass than during control sessions, with year producing variable effects. We found evidence that parents experiencing reduced broods behave as if recurring predation is a risk, but we found no evidence that parents with enlarged broods were responding to inappropriate cues. Instead, parent sparrows may be behaving prudently and avoid costs of reproduction when faced with either broods that are too small or too large. We modified a published model of optimal care, mimicked our empirical manipulation, and found that the model replicated our results provided cost and benefit curves were of a particular shape. Variation in ecology among years might affect the exact nature of the relationship between care and either current or residual reproductive value. Other data from the study population support this conclusion.

Significance statement

Parent animals often adjust their levels of care in response to manipulations of offspring value, but considerable variation in these responses exists. This suggests either a mismatch between manipulation and natural cues or undetected subtleties in the fitness consequences of care. Over 4 years, we conducted manipulations of offspring number in the biparental house sparrow (Passer domesticus). We found little evidence that parents misinterpreted cues regarding the change in number, but they behaved differently depending on the year of the manipulation. A model recovered the observed patterns if a parameter influencing the curve relating offspring fitness to levels of care was altered. This parameter should vary with food supply, and our data suggested that this varied in the years of our study. Our results emphasize that predictions about patterns of parental care are risky without attending to the shapes of fitness curves and that some organisms may be particularly sensitive to food supply.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data files associated with results in this paper have been archived with Dryad under the DOI: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.cs673qg.

References

Anderson TR (2006) Biology of the ubiquitous house sparrow - from genes to populations. Oxford University Press, New York

Ardia DR (2007) Site- and sex-level differences in adult feeding behaviour and its consequences to offspring quality in tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) following brood-size manipulation. Can J Zool 85:847–854

Askenmo C (1977) Effects of addition and removal of nestlings on nestling weight, nestling survival, and female weight loss in the pied flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca (Pallas). Ornis Scan 8:1–8

Budden AE, Wright J (2001) Begging in nestling birds. In: Nolan V Jr, Thompson CF (eds) Current Ornithology, vol 16. Springer, New York, pp 83–118

Clutton-Brock TH (1991) The evolution of parental care. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Dijkstra C, Bult A, Bijlsma S, Daan S, Meijer T, Zijlstra M (1990) Brood size manipulations in the kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) - effects of offspring and parent survival. J Anim Ecol 59:269–285

García-Navas V, Sanz JJ (2010) Flexibility in the foraging behavior of blue tits in response to short-term manipulations of brood size. Ethology 116:744–754

Glassey B, Forbes S (2002) Muting individual nestlings reduces parental foraging for the brood. Anim Behav 63:779–786

Gustafsson L, Sutherland WJ (1988) The costs of reproduction in the collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis. Nature 335:813–815

Hegner RE, Wingfield JC (1987) Effects of brood size manipulations on parental investment, breeding success, and reproductive endocrinology of house sparrows. Auk 104:470–480

Högstedt G (1980) Evolution of clutch size in birds: adaptive variation in relation to territory quality. Science 210:1148–1150

Kilner RM, Noble DG, Davies NB (1999) Signals of need in parent-offspring communication and their exploitation by the common cuckoo. Nature 397:667–672

Klomp H (1970) Determination of clutch-size in birds - a review. Ardea 58:1–125

Kluijver HN (1933) Bijdrage tot de biologie en de ecologie van de spreeuw (Sturnus vulgaris L.) gedurende zijn voortplantingstijd. Med Plantenziektenk Dienst 69:1–145

Kvarnemo C (2010) Parental care. In: Westneat DF, Fox CW (eds) Evolutionary behavioral ecology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 451–467

Lack D (1947) The significance of clutch-size. Ibis 89:302–352

Lack D (1954) The natural regulation of animal numbers. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Leonard M, Horn A (1996) Provisioning rules in tree swallows. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 38:341–347

Leonard ML, Horn AG (2006) Age-related changes in signalling of need by nestling tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor). Ethology 112:1020–1026

Magrath MJL, Janson J, Komdeur J, Elgar MA, Mulder RA (2007) Provisioning adjustments by male and female fairy martins to short-term manipulations of brood size. Behaviour 144:1119–1132

Martin TE, Scott J, Menge C (2000) Nest predation increases with parental activity: separating nest site and parental activity effects. Proc R Soc Lond B 267:2287–2293

Martins TLF, Wright J (1993) Cost of reproduction and allocation of food between parents and young in the swift (Apus apus). Behav Ecol 4:213–223

Mathot KJ, Olsen AL, Mutzel A, Araya-Ajoy YG, Nicolaus M, Westneat DF, Wright J, Kempenaers B, Dingemanse NJ (2017) Provisioning tactics of great tits (Parus major) in response to long-term brood size manipulations differ across years. Behav Ecol 28:1402–1413

Mock DW, Schwagmeyer PL, Parker GA (2005) Male house sparrows deliver more food to experimentally subsidized offspring. Anim Behav 70:225–236

Mock DW, Schwagmeyer PL, Dugas MB (2009) Parental provisioning and nestling mortality in house sparrows. Anim Behav 78:677–684

Moreno J, Cowie RJ, Sanz JJ, Williams RSR (1995) Differential response by males and females to brood manipulations in the pied flycatcher - energy expenditure and nestling diet. J Anim Ecol 64:721–732

Nicolaus M, Mathot KJ, Araya-Ajoy YG, Mutzel A, Wijmenga JJ, Kempenaers B, Dingemanse NJ (2015) Does coping style predict optimization? An experimental test in a wild passerine bird. Proc R Soc B 282:20142405

Nur N (1984) The consequences of brood size for breeding blue tits I. Adult survival, weight change and the cost of reproduction. J Anim Ecol 53:479–496

Orell M, Koivula K (1988) Cost of reproduction - parental survival and production of recruits in the willow tit Parus montanus. Oecologia 77:423–432

Pelletier K, Oedewaldt C, Westneat DF (2016) Surprising flexibility in parental care revealed by experimental changes in offspring demand. Anim Behav 122:207–215

R Development Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org

Redondo T, Castro F (1992) Signaling of nutritional need by magpie nestlings. Ethology 92:193–204

Reznick D, Nunney L, Tessier A (2000) Big houses, big cars, superfleas and the costs of reproduction. Trends Ecol Evol 15:421–425

Ringsby TH, Berge T, Saether BE, Jensen H (2009) Reproductive success and individual variation in feeding frequency of house sparrows (Passer domesticus). J Ornithol 150:469–481

Royle NJ, Smiseth PT, Kölliker M (2012) The evolution of parental care. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Santos ESA, Nakagawa S (2012) The costs of parental care: a meta-analysis of the trade-off between parental effort and survival in birds. J Evol Biol 25:1911–1917

Sanz JJ, Tinbergen JM (1999) Energy expenditure, nestling age, and brood size: an experimental study of parental behavior in the great tit Parus major. Behav Ecol 10:598–606

Schwagmeyer PL, Mock DW, Parker GA (2002) Biparental care in house sparrows: negotiation or sealed bid? Behav Ecol 13:713–721

Smith HG, Kallander H, Fontell K, Ljungstrom M (1988) Feeding frequency and parental division of labor in the double-brooded great tit Parus major - effects of manipulating brood size. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 22:447–453

Tammaru T, Horak P (1999) Should one invest more in larger broods? Not necessarily. Oikos 85:574–581

Tinbergen JM, Daan S (1990) Family-planning in the great tit (Parus major) - optimal clutch size as integration of parent and offspring fitness. Behaviour 114:161–190

Trivers RL (1972) Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campell B (ed) Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871–1971. Aldine-Atherton, Chicago, pp 136–179

Vitousek MN, Jenkins BR, Hubbard JK, Kaiser SA, Safran RJ (2017) An experimental test of the effect of brood size on glucocorticoid responses, parental investment, and offspring phenotype. Gen Comp Endocrinol 247:97–106

Westneat DF, Stewart IRK, Woeste EH, Gipson J, Abdulkadir L, Poston JP (2002) Patterns of sex ratio variation in house sparrows. Condor 104:598–609

Westneat DF, Stewart IRK, Hatch MI (2009) Complex interactions among temporal variables affect the plasticity of clutch size in a multi-brooded bird. Ecology 90:1162–1174

Westneat DF, Hatch MI, Wetzel DP, Ensminger AL (2011) Individual variation in parental care reaction norms: integration of personality and plasticity. Am Nat 178:652–667

Westneat DF, Bókony V, Burke T, Chastel O, Jensen H, Kvalnes T, Lendvai Á, Liker A, Mock D, Schroeder J, Schwagmeyer PL (2014) Multiple aspects of plasticity in clutch size vary among populations of a globally distributed songbird. J Anim Ecol 83:876–887

Williams GC (1966) Natural selection costs of reproduction and a refinement of lacks principle. Am Nat 100:687–690

Winkler DW (1987) A general model for parental care. Am Nat 130:526–543

Winkler DW, Wallin K (1987) Offspring size and number - a life-history model linking effort per offspring and total effort. Am Nat 129:708–720

Wright J, Cuthill I (1990) Biparental care: short-term manipulation of partner contribution and brood size in the starling, Sturnus vulgaris. Behav Ecol 1:116–124

Wright J, Hinde C, Fazey I, Both C (2002) Begging signals more than just short-term need: cryptic effects of brood size in the pied flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:74–83

Acknowledgments

We thank the managers and staff at Maine Chance and Coldstream Farms for accommodating us in the midst of their daily routine. We are deeply indebted to the many people who helped in the field (Jonathan Brown, Stephanie Cervino, David Moldoff, Kat Sasser, Dan Wetzel, Chelsey Oedewaldt, Kate Pelletier, and Becky Fox) and with the scoring of video files (Jonathan Brown, Annie Griggs, Laura Westneat, Jamile Naciemento, and Stephanie Cervino). We also appreciate many useful suggestions on the manuscript from Allyssa Kilanowski, Allison McLaughlin, Tim Salzman, Eduardo Santos, Kat Sasser, Jonathan Wright, and several anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This project was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (IOS1257718) and the University of Kentucky.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All basic activities and the manipulation described were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky (protocols 2007-0227 and 2012-0948).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by M. Leonard

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 141 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Westneat, D.F., Mutzel, A. Variable parental responses to changes in offspring demand have implications for life history theory. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 73, 130 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2747-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2747-z