Abstract

Purpose

Compression of the peroneal nerve is recognized as a common cause of falls. The superficial course of the peroneal nerve exposes it to trauma and pressure from common activities such as crossing of legs. The nerve can be exposed also to distress due to metabolic problems such as diabetes. The purpose of our manuscript is to review common peroneal nerve dysfunction symptoms and treatment as well as provide a systematic assessment of its relation to falls.

Methods

We pooled the existing literature from PubMed and included studies (n = 342) assessing peroneal nerve damage that is related in any way to falls. We excluded any studies reporting non-original data, case reports and non-English studies.

Results

The final systematic assessment included 4 articles. Each population studied had a non-negligible incidence of peroneal neuropathy. Peroneal pathology was found to be consistently associated with falls.

Conclusion

The peroneal nerve is an important nerve whose dysfunction can result in falls. This article reviews the anatomy and care of the peroneal nerve. The literature review highlights the strong association of this nerve’s pathology with falls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The peroneal (or fibular) nerve is a major lower limb nerve. Recently, there has been increased recognition of the association between peroneal nerve dysfunction and fall risk. This paper reviews the common peroneal nerve anatomy, common pathology, symptoms, testing and treatments. This study also pools the literature with a systematic assessment of the peroneal nerve and falls. The aim of this paper is to provide clinicians with a better understanding of this common condition and its relation to falls.

Anatomy and function

The peroneal nerve originates from the posterior divisions of L4-S2, which then form the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve bifurcates into the tibial and peroneal nerves proximal to the popliteal fossa. The common peroneal nerve courses posterolaterally just posterior to the long head of the biceps femoris. The nerve then moves anteriorly wrapping around the fibular neck, 2 cm distal to the fibular head, and passes beneath the lateral compartment on the calf. At or near the fibular neck, the nerve divides into its deep and superficial branches (Fig. 1). The deep peroneal nerve runs within the anterior compartment of the leg between the extensor hallucis longus muscle and the tibialis anterior muscle. It continues down the anterior tibia ultimately terminating between the 1st and 2nd toes. The superficial peroneal runs in the lateral compartment of the leg, before reaching the dorsum of the ankle and foot [1,2,3,4].

The peroneal nerve is a sensory-motor nerve. The motor function consists of dorsiflexion of the foot and toe extension through the deep peroneal branch and ankle eversion through the superficial branch. The sensory component of the superficial peroneal nerve supplies the dorsum of the foot except for the webspace between the first and second toes which is supplied by the deep peroneal nerve [1].

Dysfunction, symptoms, physical and diagnostic testing

The common peroneal nerve is at risk of compression and injury as it wraps around the fibular neck. At this location, the nerve is superficial and is transitioning beneath the lateral compartment muscles resulting in a higher exposure to trauma and swelling. Consequently, common aetiologies for peroneal dysfunction are mechanical-related, such as injuries and surgery around the knee. Mechanical, non-traumatic causes of peroneal nerve compression include too tight bandages, prolonged leg crossing and positioning during anaesthesia [2, 3, 5].

There are also non-mechanical reasons for peroneal dysfunction, such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and polyarteritis nodosa [6], but diabetes is by far the most common. Diabetes is a high prevalence disease impacting 19.3% of adults older than 65. Diabetes is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity especially impacting peripheral nerves such as the peroneal nerve [7, 8]. High blood sugar, reduced blood flow and high triglyceride and cholesterol levels work in synergy to cause peripheral nerve damage. Studies assessing peroneal nerve compression in patients with diabetes show a high incidence ranging from 10 to 60% depending on population and definition [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Peroneal nerve symptoms range in severity with mild symptoms often unrecognized. Patients may complain of lateral knee pain or frequent tripping. Patients may relate a “drop” foot and tripping accidents catching their foot on uneven surfaces. Sensory symptoms may be numbness on the dorsum of the foot or complaints of a numb, ticklish sensation from the upper lateral calf [15].

The physical examination starts with sensory testing, which can be done by monofilament or Ten-Test sensory examinations in the superficial and deep sensory distributions [16]. Motor testing includes assessing ankle and toe dorsiflexion and ankle eversion. Slight weakness compared to the contralateral side can help localize the pathology. Provocative tests including Tinel and Scratch collapse tests at the fibular neck are also part of the examination [17,18,19] (Supplementary Material, Video 1).

The diagnostic testing can comprise an electrodiagnostic evaluation, which is more useful in diagnosing a neuropathy with axonal deficits and can help localize a more severe peroneal neuropathy [20]. In milder cases, nerve conduction studies of the peroneal nerve are often normal, limiting the usefulness of electrodiagnostic testing [21]. Imaging, in the form of ultrasound and magnetic resonance neurography, is emerging as an additional tool to identify a swollen peroneal nerve [22]. Ultrasound holds promise as it already has been successfully used to diagnose other entrapment neuropathies such as carpal tunnel syndrome [23].

Treatments

There are several non-surgical treatments for peroneal nerve compression. A systematic review with meta-analysis [24] found exercise was helpful for patients with diabetic peripheral and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Supplements such as vitamin B α-lipoic acid have shown some benefits [25, 26]. Unconventional therapies such as moxibustion were found to be effective in increasing sensory-nerve conduction velocity [27].

Surgical decompression of the common peroneal nerve is a common treatment with increasingly robust evidence of efficacy. A small oblique incision distal to the fibular head provides adequate exposure (Figs. 2 and 3). The proximal nerve is isolated and then neurolysis continues distally including both the deep and superficial branches [28].

A recent meta-analysis found that decompression of the common peroneal nerve is safe and effective with a log(OR) of a favourable outcome after neurolysis of 3.38 (95% CI, 2.29–4.48) [29].

Methods for rapid systematic assessment

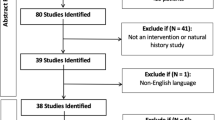

A systematic assessment of the common peroneal nerve and its relation to falls was conducted; since this study did not involve contact with patients nor animals, no ethics committee was necessary to assess compliance with Human and Animal Rights. This systematic assessment follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) approach [30], including studies that are considered peroneal nerve damage and falls.

The initial PubMed search was implemented on September 1, 2022 and used the following search string: ((perone* OR fibul*) AND nerve* AND (Fall* OR Fell OR Slip* OR Trip* OR Stumbl* OR Collaps*)) AND (("1000/01/01"[Date—Publication]: "2022/09/01"[Date—Publication])) NOT (“congress”[pt] OR “editorial”[pt] OR “meta analysis”[pt] OR “systematic review”[pt] OR review[pt]).

We included articles if they were human-based studies assessing peroneal nerve damage that is related in any way to falls. We excluded studies that did not use English as a language, systematic reviews, opinions, editorials, congress publications, meta-analyses and case reports.

Data extraction

Data was extracted by one reviewer (AC). Doubt on extracted data was discussed with an independent arbiter (CC). The following data were extracted (main text and/or supplementary material): country of origin, population number, age (median), main pathology, prevalence of peroneal neuropathy and fall association reported.

Results

Of the 342 articles retrieved from PubMed, 296 were ruled out after title screening; 36 were excluded after abstract screening; and six were excluded after full-text screening. A total of four articles were selected for data extraction (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

All the selected studies were published by authors affiliated with institutions based in North America [31,32,33,34].

Demographics

The total enrolled population was 3584 individuals, with a mean age of 60.8 and mean gender distribution of 47.8% females.

The study populations were taken from plastic surgery clinics [31] and general medicine wards [32] and focused on diabetic patients [33, 34].

Prevalence of peroneal neuropathy

One study [34] assessed equilibrium and stability in diabetic patients having peroneal neuropathy. The following results refer to the remaining 3 studies. One study found a prevalence of 3.3% subclinical peroneal neuropathy in their community-dwelling population [31]. The same first author, in another study, reported a prevalence of 67% of their inpatient sample had at least one sign of subclinical peroneal neuropathy, and 31% of patients had two signs, meeting the definition of subclinical peroneal neuropathy [32]. Finally, a prevalence of 22.5% was found in a diabetic inpatients’ sample, having “loss of light touch discrimination” in the peroneal nerve territory [33].

Association with falls

Every study reported an association between peroneal nerve dysfunction and falls.

The community dwellers with subclinical peroneal neuropathy were 3.7 times more likely to have a self-reported fall two or more times in the past year [31]. Another study found that patients, who had subclinical peroneal neuropathy, were 4.7 times more likely to have a self-reported fall in the past year, while patients who presented just one sign of subclinical peroneal neuropathy were 2.9 times more likely to self-report a fall [32]. Postural instability, and therefore the possibility of falling, was found to increase linearly with the severity of the neuropathy (p < 0.05), heedlessly of vision [34]. Schwartz et al. [33] found an association between decreasing nerve response amplitude in the peroneal nerve with falls with an odds ratio of 1.71 (CI: 1.19–2.44).

Discussion

Common peroneal compression is a common nerve entrapment with incidence similar to other compression neuropathies such as ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. The systematic assessment found a strong association between peroneal nerve neuropathy and falls. Clinicians should have a heightened awareness for this condition in elders, people with diabetes and those complaining of frequent stumbles. The first step to improving outcomes is recognition. Identification of this neuropathy relies heavily on history and physical exam. Conservative treatment can be attempted, but if symptoms persist, surgical decompression is an effective alternative. Considering these findings, we argue that increased screening of at-risk patients aimed to recognize early signs of peroneal neuropathy might be useful to lighten the toll falls take on society.

References

Khan IA, Mahabadi N, D’Abarno A, Varacallo M (2022) Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, leg lateral compartment. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519526/. Accessed 2 Aug 2022

De Maeseneer M, Madani H, Lenchik L, KalumeBrigido M, Shahabpour M, Marcelis S, de Mey J, Scafoglieri A (2015) Normal anatomy and compression areas of nerves of the foot and ankle: US and MR imaging with anatomic correlation. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc 35(5):1469–1482. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2015150028

Bromberg MB (2018) Peripheral neuropathies a practical approach. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316135815.011

Hardin JM, Devendra S (2022) Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, calf common peroneal (fibular) nerve. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532968/. Accessed 9 Aug 2022

Bouche P (2013) Compression and entrapment neuropathies. Handb Clin Neurol 115:311–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52902-2.00019-9

Bray A (2017) Essentials of physical medicine and rehabilitation: musculoskeletal disorders, pain, and rehabilitation. Occup Med Oxf Engl 67(1):80–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqw129

World Health Organization - Who, “Diabetes Fact-Sheet”. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed on 8/08/22

Sinclair A, Saeedi P, Kaundal A, Karuranga S, Malanda B, Williams R (2020) Diabetes and global ageing among 65–99-year-old adults: findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 162:108078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108078

Siemionow M, Zielinski M, Sari A (2006) Comparison of clinical evaluation and neurosensory testing in the early diagnosis of superimposed entrapment neuropathy in diabetic patients. Ann Plast Surg 57(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000210634.98344.47

Aszmann O, Tassler PL, Dellon AL (2004) Changing the natural history of diabetic neuropathy: incidence of ulcer/amputation in the contralateral limb of patients with a unilateral nerve decompression procedure. Ann Plast Surg 53(6):517–522. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000143605.60384.4e

Llewelyn JG (2003) The diabetic neuropathies: types, diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74 Suppl 2:ii15–ii19. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.74.suppl2.ii15

Rinkel WD, Castro Cabezas M, Setyo JH, Van Neck JW, Coert JH (2017) Traditional methods versus quantitative sensory testing of the feet at risk: results from the Rotterdam Diabetic Foot Study. Plast Reconstr Surg 139(3):752e–763e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003047

Rota E, Quadri R, Fanti E, Isoardo G, Poglio F, Tavella A, Paolasso I, Ciaramitaro P, Bergamasco B, Cocito D (2005) Electrophysiological findings of peripheral neuropathy in newly diagnosed type II diabetes mellitus. J Peripher Nerv Syst 10(4):348–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.00046.x

Vinik A, Mehrabyan A, Colen L, Boulton A (2004) Focal entrapment neuropathies in diabetes. Diabetes Care 27(7):1783–1788. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.7.1783

Katirji B (2022) Disorders of peripheral nerves. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ (eds) Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, 8th edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, p chap 106

Strauch B, Lang A, Ferder M, Keyes-Ford M, Freeman K, Newstein D (1997) The ten test. Plast Reconstr Surg 99(4):1074–1078. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199704000-00023

Uddin Z, MacDermid J, Packham T (2013) The ten test for sensation. J Physiother 59(2):132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70171-1

Pisquiy JJ, Carter JT, Gonzalez GA (2022) Validity of using the scratch collapse test in the lower extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg 150(1):194e–200e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000009237

Chikai M, Ozawa E, Takahashi N, Nunokawa K, Ino S (2015) Evaluation of the variation in sensory test results using Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference, pp 1259–1262. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2015.7318596

Thatte H, De Jesus O (2022) Electrodiagnostic evaluation of peroneal neuropathy. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563251/. Accessed 9 Aug 2022

Lu JC, Dengler J, Poppler LH, Van Handel A, Linkugel A, Jacobson L, Mackinnon SE (2020) Identifying common peroneal neuropathy before foot drop. Plast Reconstr Surg 146(3):664–675. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000007096

Oosterbos C, Decramer T, Rummens S, Weyns F, Dubuisson A, Ceuppens J, Schuind S, Groen J, van Loon J, Rasulic L, Lemmens R, Theys T (2022) Evidence in peroneal nerve entrapment: a scoping review. Eur J Neurol 29(2):665–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15145

Lin TY, Chang KV, Wu WT, Özçakar L (2022) Ultrasonography for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: an umbrella review. J Neurol 269(9):4663–4675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11201-z

Streckmann F, Balke M, Cavaletti G, Toscanelli A, Bloch W, Décard BF, Lehmann HC, Faude O (2021) Exercise and neuropathy: systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med 52(5):1043–1065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01596-6

Farah S, Yammine K (2022) A systematic review on the efficacy of vitamin B supplementation on diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Nutr Rev 80(5):1340–1355. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab116

Han T, Bai J, Liu W, Hu Y (2012) Therapy of endocrine disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of α-lipoic acid in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Endocrinol 167(4):465–471. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-12-0555

Tan Y, Hu J, Pang B, Du L, Yang Y, Pang Q, Zhang M, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Ni Q (2020) Moxibustion for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis following PRISMA guidelines. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(39):e22286. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022286

Corriveau M, Lescher JD, Hanna AS (2018) Peroneal nerve decompression. Neurosurg Focus 44(VideoSuppl1):V6. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.1.FocusVid.17575

Chow AL, Levidy MF, Luthringer M, Vasoya D, Ignatiuk A (2021) Clinical outcomes after neurolysis for the treatment of peroneal nerve palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Plast Surg 87(3):316–323. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002833

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269, W64. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Poppler LH, Yu J, Mackinnon SE (2020) Subclinical peroneal neuropathy affects ambulatory, community-dwelling adults and is associated with falling. Plast Reconstr Surg 145(4):769e–778e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000006637

Poppler LH, Groves AP, Sacks G, Bansal A, Davidge KM, Sledge JA, Tymkew H, Yan Y, Hasak JM, Potter P, Mackinnon SE (2016) Subclinical peroneal neuropathy: a common, unrecognized, and preventable finding associated with a recent history of falling in hospitalized patients. Ann Fam Med 14(6):526–533. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1973

Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, Feingold KR, de Rekeneire N, Strotmeyer ES, Shorr RI, Vinik AI, Odden MC, Park SW, Faulkner KA, Harris TB (2008) Health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes-related complications, glycemic control, and falls in older adults. Diabetes Care 31(3):391–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1152. Erratum in: Diabetes Care. 2008 May;31(5):1089

Boucher P, Teasdale N, Courtemanche R, Bard C, Fleury M (1995) Postural stability in diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care 18(5):638–645. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.18.5.638

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported by the Palo Alto Veterans Hospital.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This material is the result of work supported by the Palo Alto Veterans Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC researched the literature, drafted the manuscript, and performed the systematic assessment.

EH drafted the manuscript and provided insight and important intellectual content.

HD performed the illustration.

CC drafted the manuscript, provided insight and important intellectual content, and supervised the entire process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval, consent to participate, consent to publish

Not applicable, being this a review paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Level of evidence: IV, retrospective study

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Video 1. Clinical examination of common peroneal nerve compression, performed by Dr. PhD Elisabet Hagert. (MP4 59014 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Capodici, A., Hagert, E., Darrach, H. et al. An overview of common peroneal nerve dysfunction and systematic assessment of its relation to falls. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 46, 2757–2763 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-022-05593-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-022-05593-w