Abstract

Purpose

A formalised, universally accepted, radiological staging system of gleno-humeral joint osteonecrosis (ON) is lacking. Consequently, there is absence of a standardised management strategy. The aim is to propose a simple radiological staging system of gleno-humeral joint ON based on principles of the Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) Society and review of clinical practice.

Methods

A radiographic and clinical review of 45 patients with haematological-induced gleno-humeral ON was performed. The related management plans were analysed and categorised.

Results

Analysis divided the disease into stages 0–4. Non-interventional management was the first-line treatment in stages 1–2. If unsuccessful, arthroscopic core decompression was performed. Patients with stages 3–4 were initially managed conservatively. If unsuccessful, in younger patients, arthroscopic joint debridement and capsular release was trialled. In older patients, or where this approach failed, shoulder arthroplasty was advised.

Conclusion

The simple radiological classification assessed is useful to the provision of a standardised staged management strategy of gleno-humeral ON.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atraumatic gleno-humeral joint osteonecrosis (ON) is an infrequent primary cause of shoulder pain in newly presenting patients. The humeral head is secondary only to the femoral head as the most common locus for atraumatic ON [20]. Unmanaged ON carries the risk of deleterious progression in conjunction with significant clinical and functional impediments [11, 18]. ON has multiple aetiologies. These include chronic renal disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, asthma, prolonged systemic steroid use and bone infarcting haematological diseases [2, 16, 17]. Sickle cell disease (SCD), thalassaemia and G6PD deficiency are recognised haematological conditions that can induce osteonecrosis [10]. Such diseases often manifest in younger patients and subsequently require a lifetime management approach that encompasses care for both the underlying conditions and the affected joint itself. Optimal care delivery for such a complex issue requires a multi-disciplinary and holistic approach.

Osteonecrosis of the hip has benefited from internationally recognised staging and classification systems which have developed over time [4, 15, 22, 23]. The Association of Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) has provided a platform for debate and guidance for universal principles for classification of ON in large joints [6, 15, 22]. The recognition of ‘staging’ is the basis of each classification for ON, as each patient is very likely to travel through various ‘stages’ during their individual disease process. Treatment decisions are often based on the ‘stage’ of the disease process, irrespective of the underlying aetiology of the disease. For the hip joint, this recognition has provided useful treatment guidelines.

However, gleno-humeral joint ON has yet to receive an internationally recognised specific staging system that would attract wide-spread adoption and application. Historic studies have modified the Ficat and Arlet [4] classification in an attempt to have a staged shoulder ON system on which to centre their work on [1, 15]. Such work however was conducted over 40 years ago and subsequent shoulder ON studies have not replicated the same staging approach in their analyses or study designs.

The benefits of having a modern and universally accepted system include the potential for improved clinician communication, improved research and progression towards a standardised staged disease management strategy.

This study radiologically and clinically assessed an adult population of patients with haematological-induced gleno-humeral joint ON at all disease stages. This patient group is noteworthy due to the significant systemic disease process, affecting often more than one joint as well as requiring a multi-disciplinary approach between the haematologist and associated medical teams, the pain specialist and orthopaedic surgeon. The more important is a rational approach to treatment of the joint disease. The aim of our study is to propose a simple radiological staging system of gleno-humeral joint ON based upon radiological findings and the ARCO principles. The study secondarily aims to apply the classification and correlate with our clinical observations in order to categorise management by ON stage and subsequently propose a staged management strategy.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The present study is a single-centre retrospective cohort review of adult patients with haematological-induced atraumatic gleno-humeral joint ON who presented to the shoulder unit with active regional symptoms. The patients were included into the departmental shoulder database. Patients were excluded from the study if they had any evidence of shoulder girdle trauma, previous shoulder joint infection, or previous cervical spine trauma or brachial plexopathy.

Patient demographics

The study population comprised of 45 patients (25 male, 20 female, average age 40 years, range 21–62 years). All patients had a haematological condition as the aetiology for their gleno-humeral ON. All patients in the study population had a diagnosis of sickle cell disease whilst six of the patients had a dual diagnosis of SCD and another haematological condition (SCD + thalassaemia n = 1; SCD + G6PD deficiency n = 5; SCD only n = 39). The SCD genotype profile of the patient population was recorded (HBSS SCD n = 29; HBSC SCD n = 10, HBSS SCD + G6PD n = 4; HBSB SCD + G6PD n = 1; HBSS SCD + thalassaemia n = 1). Concurrent history of hip ON was noted in n = 40 patients.

Radiological and staging assessment

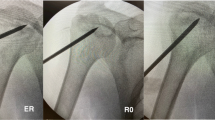

All patients had comprehensive radiographic evaluation with anteroposterior (AP) views and axillary gleno-humeral views at their first clinic attendance. These were used to classify gleno-humeral ON based upon the parameters set out by ARCO; in specific, the ARCO classification outlined by Gardeniers (1993) [4] following an international work group meeting was applied. A simplified version was adapted to aid clinical evaluation [Table 1]. The classification was adapted pragmatically from the hip joint to the gleno-humeral joint. Stage 0 (all images normal), Stage 1 (radiograph and CT normal, MRI abnormal) and Stage 2 (radiographic evidence of sclerosis, osteolysis and focal porosis but spherical outline of head intact) were analysed as for the hip joint. Stage 3, in the hip characterised by the crescent sign on the lateral view with flattening of the head due to subchondral collapse, was adapted to ‘subchondral collapse with preservation of joint space’. This was differentiated from Stage 4 (advancing joint destruction due to secondary osteoarthritis (OA) and loss of joint space, again similar to the classification of the hip). Later versions of the classification include additional stages specifying articular involvement; however, these were regarded as less relevant for the gleno-humeral joint. Three consultant shoulder surgeons independently assessed these images and classified the ON stage at first presentation with respect to the classification. Inter-observer variation was assessed and statistically analysed.

The individual management of each patient was recorded and assessed. Subsequently, the prescribed management pathways were grouped by classification stage. This enabled a staged management pathway to be elucidated.

Outcome assessment

Subjective assessment was conducted with pre- and post-treatment visual analogue scores (VAS) regarding shoulder pain. On this, VAS ten out of ten represented the worst pain and conversely zero out of ten no pain. As for the hip at present, no standard outcome score is validated for osteonecrosis of the shoulder as ON often presents with a systemic effect, in particular residual pain from other sources as well as limited function by the individual degree of the haematological disease. As such outcome measurements of only the shoulder may provide an incomplete assessment [12]. All patients in this study population had ON secondary to systemic haematological diseases. A post-treatment patient satisfaction was also recorded. This was graded out of ten with a maximum satisfaction score being ten and the least being zero. The addition of the satisfaction score whilst subjective aimed to assess a more holistic outcome measure.

Results

Radiographic evaluation

Analysis using the staging and classification system as described demonstrated no patients had Stage 0 disease. The percentage of patients with stages 1, 2, 3 and 4 disease were 40, 36, 9 and 16% respectively [Table 1, Fig. 1]. The radiographic assessment allowed clear differentiation of the stages as outlined. The inter-observer correlation regarding classification was 0.9.

a AP shoulder radiograph of patient with Stage 1 gleno-humeral joint changes. b AP and axial shoulder radiographs of patient with Stage 2 gleno-humeral joint changes. c AP and axial shoulder radiographs of patients with Stage 3 gleno-humeral joint changes. d AP and axial shoulder radiographs of patients with Stage 4 gleno-humeral joint changes

Staged gleno-humeral ON management

Stage 1–2

Non-interventional management was the first-line treatment that was offered in all stages [Table 2]. The non-interventional managements offered were analgesics, physiotherapy, corticosteroid injection or a combination of these. Patients at Stage 1 and 2 had minimal radiographic findings (Stage 1) and importantly, a preserved radiological outline of the humeral head (Stage 2). Thus, non-interventional management was prescribed most commonly in the stages 1 and 2. No patients with Stage 1 disease had surgery prescribed at the initial clinical review and the majority of patients with Stage 2 disease also initially were managed with conservative therapies. If the conservative management options were insufficient then patients with Stage 2 disease were offered arthroscopy, humeral head core decompression, joint debridement and decompression.

Stage 3–4

Patients at Stage 3 showed clear radiographic alteration of the outline of the humeral head, but importantly with preservation of the joint space in all views. Thus, patients with Stage 3 disease when the conservative management options failed were treated with joint-preserving treatments as arthroscopic capsular release, gleno-humeral joint debridement, bursectomy and subacromial decompression procedures. In patients with advanced radiographic OA, Stage 4 disease, if conservative therapies failed, a variety of surgical procedures were performed. These included an arthroscopic approach incorporating capsular release, gleno-humeral joint debridement, subacromial decompression and shoulder arthroplasty. There was variation in the type of shoulder arthroplasty performed. The average age of patient undergoing shoulder arthroplasty was 51 years old (range 44–59 years). Arthroplasty included glenoid-sparing and non-glenoid-sparing surgery. The glenoid-sparing hemiarthroplasty was performed in the younger patients with an intact rotator cuff and less advanced glenoid changes. Reverse shoulder replacement occurred in the older, lower demand, patient with rotator cuff deficiency.

Staged ON outcomes

All patient groups, independent of stage, demonstrated improvement in VAS scores between pre- and post-treatment [Fig. 2]. The maximal effect of conservative treatment was seen in those with Stage 1 and the least with Stage 4 gleno-humeral ON. Arthroscopic surgical intervention in the guise of arthroscopic debridement, core decompression or capsular release had the greatest impact in those with earlier stage ON. One of the two patients with Stage 3 ON who underwent arthroscopic debridement and capsular release were subsequently considered for arthroplasty because of poor on-going clinical symptoms. A limited number of Stage 4 patients underwent a variety of different arthroplasty procedures. Improvement of VAS scores was noted in this group along with positive post-treatment patient satisfaction scores. There were no significant complications noted within this subgroup.

Discussion

Previous studies have assessed a variety of surgical and non-surgical methods in the management of gleno-humeral ON [5]. However, whilst these studies sought to assess the clinical efficacy of a particular treatment protocol, they often failed to target to a specific stage of gleno-humeral ON disease. This is likely to be because no work has specifically attempted to provide a simple unified radiographic staging and classification system for gleno-humeral ON that has gained wide-spread clinical traction. This lack of a universally applied classification and staging system weakens the interpretation of the results of these different surgical treatments.

This study proposes a simple and pragmatic radiographic classification for gleno-humeral ON based on the ARCO classification as outlined by Gardeniers [6] [Table 1]. This subsequently offers the opportunities to undertake meaningful specific research into the optimal management of gleno-humeral ON at the various stages. Through this approach, an accepted staged management strategy for such patients is a possibility. This study has demonstrated conservative treatment to be more effective with regard to symptom-control in the earlier stages of gleno-humeral ON as compared to the later ones. An arthroscopic approach with core decompression was seen to have positive results in Stage 2 whilst in Stage 3, arthroscopic debridement and capsular release was used primarily as a method to retain the native joint for longer. Patients at Stage 3 have been identified at a true point of transition, and surgical intervention aiming to preserve the gleno-humeral joint has been pursued in spite of wide-spread articular involvement. This approach is of especial relevance in the younger age groups although the impact of joint-preserving surgery over time may be limited. Here, clearly further longitudinal research is required. Shoulder arthroplasty was found to have a role in Stage 4 patients with advanced osteoarthritic changes and less age-based activity demands and expectations.

Previous systemic reviews into the management of gleno-humeral ON are limited [5]. A variety of different surgical techniques have been described to deliver improved clinical outcomes for patients with symptomatic ON by a number of authors [1, 3, 8, 9, 14, 19, 21]. These include core decompression, autologous concentrated bone marrow grafting, hemiarthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. The use of core decompression humeral head mirrors practice that is often seen in the management of hip ON at a similar stage. Humeral head core decompression aims to reduce intra-osseous pressure to restore the normal vascular flow. The outcomes following humeral head core decompression have historically shown a positive effect in patients with early stage disease [5, 8, 13, 16] with symptomatic benefit beyond five years following treatment. Core decompression can be performed open or with arthroscopic assistance. The benefit of an arthroscopic approach being that it offers an opportunity for a complete examination of the articular cartilage, the potential for joint debridement, decompression, capsular release or the identification and management of any other related joint issues. Arthroscopic decompression and debridement has been shown to have limited benefits as the disease stages progress [7]. Arthroplasty is generally reserved for patients with more advanced conditions [3, 5, 9, 19, 21]. The approach advocated in this present study is based on 85% of patients at Stage 1–2 having conservative treatment and 14% undergoing arthroscopic core decompression. This contrasts against the patients at Stages 3–4 of whom 55% received surgical intervention.

The relatively young age of the study population is characteristic for ON and is a significant issue when considering the immediate surgical decision making. Interventional decisions can have a significant impact in relieving pain but concerns relating to arthroplasty in young adults are valid, especially given the higher demands that this demographic understandably have and the impact that this can have on prosthesis longevity. Studies comparing glenoid-sparing hemiarthroplasty with glenoid-inclusive arthroplasty are limited; however, the relative rate of complications is higher in the latter group potentially without a significant improvement in outcomes [3, 9]. However, these studies are limited and need to be interpreted with a judicious approach. As such, a holistic methodology is imperative to rationalise decision making whilst balancing this with bespoke lifetime surgical planning. Given these challenges, and the technically demanding nature of the surgical interventions in this patient group, management is best led by experts and experienced sub-specialists.

Haematological conditions were the aetiology of shoulder ON in this study, with SCD being the predominant cause. A previous study assessing the natural history of symptomatic humeral head osteonecrosis in adults with SCD concluded that untreated symptomatic shoulder osteonecrosis secondary to SCD had a high likelihood of progressive change requiring surgical intervention [18]. They reported 86% of their population demonstrated radiological progression and 61% needed some form of surgical intervention. The mean time between the onset of pain and radiological collapse was six years. Pre-existing hip ON or the SCD genotype ST or SC were identified as risk factors for the development of shoulder ON. Patients with postero-medial humeral head osteonecrotic lesions or early lesions of greater sizes had an elevated risk of an advanced rate of progression. The combination of an early age of onset of symptomatic shoulder ON in patients with SCD and the potential risk for swift deleterious bony changes emphasise the need for a staged multi-disciplinary treatment strategy.

This study proposes an easy to use radiological classification for patients with gleno-humeral ON and correlates management with this classification [Table 3]. Non-interventional management is the suggested first-line treatment in patients at Stages 1–2. If this fails then early progression to arthroscopic core decompression potentially in combination with subacromial decompression should be considered. In patients at Stages 3–4 if conservative therapies fail then subsequent management can be broadly split into two groups. In younger patients, an initial arthroscopic joint debridement and capsular release can be trialled. However, if patients are older or in those where this approach fails, to alleviate symptoms, shoulder arthroplasty should be considered.

It is noteworthy that patients in this study with Stage 3 disease experienced symptomatic benefits without undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, in spite of wide-spread articular involvement of the humeral head but preserved joint space. This is in comparison to patients with hip ON of a similar stage in whom arthroplasty is often routine. Speculation regarding the shoulder having a lesser role in continuous full body-weight load-bearing, as compared to the hip, may help to explain why shoulder patients may comparatively be able to delay their arthroplasty. There will be variation in the type of arthroplasty performed and this will be dependent on the individual circumstance. In the younger age groups, given the high likelihood of future revision surgeries, a glenoid-sparing approach may be more appropriate. If the glenoid is unsuitable for this approach secondary to progressive reciprocal changes or if there is rotator cuff deficiency or if the patient has lower demands then a more comprehensive arthroplasty solution is likely to be preferred.

This study has several weaknesses which are acknowledged. This is a retrospective Level IV study, with a limited population size and follow-up period, albeit in a very specific patient group. Outcomes reporting issues worth commenting on include the absence of a dedicated shoulder outcome measure. This may impact on the ability to comment on treatment pathway comparisons. However, as SCD-induced ON is a systemic disease, the isolated use of shoulder-specific outcome measures would be also problematic. In addition, there was some variation in the haematological conditions with the study population but all patients primary suffered from SCD. This offered some relative homogeneity to the aetiology.

The study presents a pragmatic adaptation of the ARCO radiological staging system to osteonecrosis of the gleno-humeral joint. This has been shown to be easily applied with good inter-observer correlation. Treatment strategies were found to be aligned with the applied classification. Particular Stage 3 was found to be relevant for the gleno-humeral joint as a transition stage, and in these patients, a joint-preservative surgical approach was possible in spite of wide-spread articular involvement of the humeral head. More longitudinal studies are required.

We are optimistic that if a simple to use, unified and ubiquitous staging system for gleno-humeral joint ON was to be widely accepted that it would improve and optimise multi-disciplinary decision making and aid future research opportunities in the management of this complex condition.

References

Cruess RL (1976) Steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the head of the humerus. Natural history and management. J Bone Joint Surg Br 58(3:313–317

Cruess RL (1978) Experience with steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the shoulder and etiologic considerations regarding osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 130:86–93

Feeley BT, Fealy S, Dines DM, Warren RF, Craig EV (2008) Hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty for avascular necrosis of the humeral head. J Shoulder Elb Surg 17(5):689–694

Ficat P, Arlet J (1973) Pre-radiologic stage of femur head osteonecrosis: diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 59(Suppl 1):26–38

Franceschi F, Franceschetti E, Paciotti M, Torre G, Samuelsson K, Papalia R, Karlsson J, Denaro V (2017) Surgical management of osteonecrosis of the humeral head: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25(10):3270–3278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-4169-z

Gardeniers JWM (1993) ARCO Committee on Terminology and Staging. ARCO Newsletter 5:79–82

Hardy P, Decrette E, Jeanrot C, Colom A, Lortat-Jacob A, Benoit J (2000) Arthroscopic treatment of bilateral humeral head osteonecrosis. Arthroscopy 16(3):332–335

Harreld KL, Marulanda GA, Ulrich SD, Marker DR, Seyler TM, Mont MA (2009) Small-diameter percutaneous decompression for osteonecrosis of the shoulder. Am J Orthop 38(7):348–354

Hattrup SJ, Cofield RH (2000) Osteonecrosis of the humeral head: results of replacement. J Shoulder Elb Surg 9(3):177–182

Hernigou P, Allain J, Bachir D, Galacteros F (1998) Abnormalities of the adult shoulder due to sickle cell osteonecrosis during childhood. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 65(1):27–32

Hernigou P, Bachir D, Galacteros F (2003) The natural history of symptomatic osteonecrosis in adults with sickle cell disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85(3):500–504

Jack CM, Howard J, Aziz ES, Kesse-Adu R, Bankes MJ (2016) Cementless total hip replacements in sickle cell disease. Hip Int 26(2):186–192

LaPorte DM, Mont MA, Mohan V, Pierre-Jacques H, Jones LC, Hungerford DS (1998) Osteonecrosis of the humeral head treated by core decompression. Clin Orthop Relat Res 355:254–260

Makihara T, Yoshioka T, Sugaya H, Yamazaki M, Mishima H (2017) Autologous concentrated bone marrow grafting for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the humeral head: a report of five shoulders in four cases. Case Report Orthop 2017:4898057. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4898057

Marcus ND, Enneking WF, Massam RA (1973) The silent hip in idiopathic aseptic necrosis: treatment by bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am 55:1351–1366

Mont MA, Maar DC, Urquhart MW, Lennox D, Hungerford DS (1993) Avascular necrosis of the humeral head treated by core decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br 75(5):785–788

Mont MA, Payman RK, Laporte DM, Petri M, Jones LC, Hungerford DS (2000) Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. J Rheumatol 27(7):1766–1773

Poignard A, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Amzallag J, Galacteros F, Hernigou P. (2012) The natural progression of symptomatic humeral head osteonecrosis in adults with sickle cell disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 18;94(2): 156–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.J.00919.

Raiss P, Kasten P, Baumann F, Moser M, Rickert M, Loew M (2009) Treatment of osteonecrosis of the humeral head with cementless surface replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(2):340–349. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00560

Sakai T, Sugano N, Nishii T, Hananouchi T, Yoshikawa H (2008) Extent of osteonecrosis on MRI predicts humeral head collapse. Clinical Orthop Relat Res 466(5):1074–1080

Smith RG, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Hattrup SJ, Schleck CD (2008) Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for steroid-associated osteonecrosis. J Shoulder Elb Surg 17(5):685–688

Steinberg ME, Hayen GD, Steinberg D (1995) A quantitative system for staging avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 77:34–41

Sugioka Y (1978) Transtrochanteric anterior rotational osteotomy of the femoral head in the treatment of osteonecrosis affecting the hip: a new osteotomy operation. Clin Orthop Relat Res (130):191–201

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Colegate-Stone, T.J., Aggarwal, S., Karuppaiah, K. et al. The staged management of gleno-humeral joint osteonecrosis in patients with haematological-induced disease—a cohort review. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 42, 1651–1659 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-3957-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-3957-0