Abstract

Purpose

To determine institutional practice requirements for personal protective equipment (PPE) in cross-sectional interventional radiology (CSIR) procedures among a variety of radiology practices in the USA and Canada.

Methods

Members of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) CSIR Emerging Technology Commission (ETC) were sent an eight-question survey about what PPE they were required to use during common CSIR procedures: paracentesis, thoracentesis, thyroid fine needle aspiration (FNA), superficial lymph node biopsy, deep lymph node biopsy, solid organ biopsy, and ablation. Types of PPE evaluated were sterile gloves, surgical masks, gowns, surgical hats, eye shields, foot covers, and scrubs.

Results

26/38 surveys were completed by respondents at 20/22 (91%) institutions. The most common PPE was sterile gloves, required by 20/20 (100%) institutions for every procedure. The second most common PPE was masks, required by 14/20 (70%) institutions for superficial and deep procedures and 12/12 (100%) institutions for ablation. Scrubs, sterile gowns, eye shields, and surgical hats were required at nearly all institutions for ablation, whereas approximately half of institutions required their use for deep lymph node and solid organ biopsy. Compared with other types of PPE, required mask and eye shield use showed the greatest increase during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Conclusion

PPE use during common cross-sectional procedures is widely variable. Given the environmental and financial impact and lack of consensus practice, further studies examining the appropriate level of PPE are needed.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

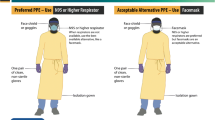

Any invasive procedure carries at least a theoretical risk of introducing infection. Surgical site infections (SSIs) are significant clinical problems associated with increased patient morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Efforts have been made in the operating room to counteract SSIs by increasing the physical barriers between the incision site and pathogens introduced from the air or body surfaces. This has led to stringent requirements for use of personal protective equipment (PPE)—scrubs, sterile gloves, sterile gowns, surgical hats, ear covers, beard covers, and disposable shoe covers—albeit based primarily on theoretical benefits rather than evidence-based practices [1,2,3,4,5]. Many of the PPE recommendations have filtered into the practice of procedures performed outside of the operating room, such as US- and CT-guided procedures, commonly referred to as cross-sectional interventional radiology (CSIR) procedures [6]. The infection rate associated with CSIR procedures is far less than is cited for SSIs, likely due to the minimal invasiveness of a skin puncture a few millimeters in diameter; however, the financial cost and environmental impact associated with the use of PPE are considerable [7, 8]. Multiple societies have published practice guidance for CSIR procedures, although there is no consensus standard addressing required PPE, and differing practices are observed anecdotally among various institutions [6, 9,10,11,12,13].

In 2020, Society of Abdominal Radiology created the Cross-sectional Interventional Radiology Emerging Technology Commission (CSIR ETC) to support radiologists performing cross-sectional procedures by researching best practices and developing practice guidelines to optimize patient outcomes. CSIR ETC currently includes 38 members from 22 institutions with geographic and practice-type diversity across the USA and Canada. The CSIR ETC members were surveyed to assess currently utilized PPE for CSIR procedures.

The main goal of this study was to determine institutional PPE requirements for common CSIR procedures. The secondary goal was to evaluate changes in PPE requirements during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods

This Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant study was exempt from institutional review board approval. An eight-question survey about PPE during CSIR procedures performed by abdominal radiologists was created using SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was sent by email to all 38 members of the SAR CSIR ETC from 22 institutions. Data regarding PPE were evaluated on a per institution basis (one respondent per institution) to mitigate undue weighting of particular institutional practices.

Most of the survey items were checkbox questions evaluating required PPE, skin preparation agents, and the use of sterile towels, paper drape, and sterile back table cover during paracentesis/thoracentesis, thyroid fine needle aspiration (FNA), superficial lymph node biopsy, deep lymph node biopsy, solid organ biopsy, and ablation. The survey asked if these procedures were performed and what types of PPE were required (sterile gloves, scrubs, sterile gown, non-sterile gown, surgical mask, surgical hat, disposable shoe covers, and eye shield). In anticipation of changes in PPE use during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, survey items evaluated proceduralist PPE requirements prior to and during the pandemic. The complete survey can be found in the Appendix.

CSIR ETC members received the survey on July 14, 2021. A follow-up reminder email to complete the survey was sent on July 28, 2021, and the survey was closed on August 4, 2021. The results were managed using Microsoft Excel for Mac and summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

The survey was completed by 26/38 (68%) members, representing 20/22 (91%) institutions in the CSIR ETC. Respondents were from 18 academic centers and 2 private practices. Of the 20 institutions represented in the responses, 20/20 (100%) performed superficial procedures (paracentesis, thoracentesis, thyroid FNA, superficial lymph node biopsy), 20/20 (100%) performed deep biopsy (deep lymph node biopsy and solid organ biopsy), and 12/20 (60%) performed ablation.

Results are graphically represented in Figs. 1, 2, and 3. Prior to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the most common PPE was sterile gloves, which were required by all institutions for every procedure. The second most common PPE was surgical masks, which were required by 14/20 (70%) institutions for superficial and deep procedures and 12/12 (100%) institutions for ablation. Scrubs, sterile gowns, eye shields, and surgical hats were required at nearly all institutions for ablation, whereas approximately half of institutions required their use for deep lymph node and solid organ biopsy. During the pandemic, eye shield and mask requirements increased far more than other PPE.

Foot covers were rarely required and only reported by 1/20 (5%) institutions for deep lymph node and solid organ biopsy and 2/12 (17%) institutions for ablation. Required non-sterile gowns were reported by 1/20 (5%) institutions for all superficial procedures and deep lymph node and solid organ biopsy. During the pandemic, 2/20 (10%) institutions added non-sterile gowns to their PPE requirements during deep lymph node and solid organ biopsy and 3/20 (15%) institutions added required non-sterile gowns during superficial procedures.

The different combinations of required PPE (e.g., “gloves and mask,” “gloves, mask, gown, and hat”) varied widely among the institutions and among procedures. For example, 13 different combinations of PPE were reported for solid organ biopsy, ranging from required use of only sterile gloves to required use of sterile gloves, scrubs, sterile gown, mask, hat, and eye shield. No more than 3 institutions shared the same combination of required PPE for solid organ biopsy. For paracentesis and thoracentesis, 16 different combinations of PPE were reported and ranged from only sterile gloves to a combination of sterile gloves, scrubs, sterile gown, mask, and hat. No more than 2 institutions shared the same combination of required PPE for paracentesis/thoracentesis. For the remaining procedures, the numbers of different PPE combinations were 14 for thyroid FNA, 13 for superficial LN biopsy, 14 for deep LN biopsy, and 5 for ablation. No similarities in required PPE use were observed between practices in the same geographic region or the same practice type (academic vs. private).

Table 1 represents the institutions reporting PPE practice that complies with recommendations from the joint practice guidelines from Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), and the Association for Radiologic and Imaging Nursing (ARIN), which include wearing scrubs, hat, mask, sterile surgical gown, and sterile gloves during percutaneous biopsy and ablation [6].

Chlorhexidine agents were preferred for skin preparation by the majority of individual respondents for all procedures, ranging from 87 to 92%. Ninety-four percent of individual respondents reported use of a sterile table cover for the back table during ablation, but this was less commonly reported in other procedures, ranging from 48 to 64%. Preference for sterile towel and sterile paper drape use also varied (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Preventing infection is important when performing any procedure and follows the dictum, primum non nocere—first, do no harm. Use of PPE is viewed as a way to protect both the patient from infection and the proceduralist from body fluid and tissue exposure, but the extent to which PPE is used during CSIR procedures is variable. These survey results demonstrate tremendous variation in PPE practices and are in keeping with a similar past survey of interventional radiologists that also showed varied use of PPE [14]. In the current survey, the majority of institutions required sterile gloves and masks for CSIR procedures prior to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, but other PPE requirements were largely inconsistent across the group. During the pandemic, required mask and eye shield use increased for all procedures (65–100% to 95–100% for masks and 45–67% to 80–92% for eye shields), although other PPE requirements continued to vary. Sterile gloves and masks seemingly represent the minimum requirements of PPE for CSIR procedures, along with eye shields during the pandemic, although a majority consensus on other elements of PPE was not evident from the survey.

The lack of consensus and the paucity of data evaluating PPE in CSIR procedures likely contribute to the practice variation observed in this survey. Several societies in radiology and other medical specialties have published practice guidelines for these procedures but make differing recommendations or do not make specific recommendations for PPE use [6, 9,10,11,12,13]. Joint practice guidelines from the SIR/AORN/ARIN recommend to mirror the operating room setting during all percutaneous biopsies and tumor ablations, requiring proceduralists to wear scrubs, hair coverings, sterile gowns, sterile gloves, and masks, although only a minority of institutions were noted in the survey to comply with this recommendation for biopsies [6]. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) Practice Parameters recommend to follow facility infection control practices, but do not provide specific guidance regarding PPE for most procedures [9]. In the literature, PPE use is usually not specified or addressed in articles describing the technique and complications of CSIR procedures, including those focused specifically on post-procedural infection. A large retrospective series evaluating infection after more than 13,000 ultrasound-guided CSIR procedures found an overall incidence of 0.1% for post-procedural infection, but the details of PPE were not included [15].

The relationship between PPE use in the operating room and the prevalence of SSIs is unclear, and the rate of infection during CSIR procedures is exceedingly low (0 to < 1%), less than the rate cited for SSIs [3,4,5, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Adopting the same standards of an operating room for CSIR procedures may be unnecessary when considering an analogous comparison in the surgical literature: minor hand and skin surgery. In Canada, the most common procedural setting for carpal tunnel surgery is an ambulatory procedure room using “field sterility,” defined by the use of a surgical mask, sterile gloves, and small sterile drape [22, 23]. No gown or hat is worn. In this setting, multiple groups have shown no difference in clinical outcomes or post-operative infections when compared to carpal tunnel surgeries performed in the traditional operating room setting [24, 25]. A similar trend has also been observed in Mohs micrographic skin surgery, where prospective trials have shown no differences in the prevalence of SSIs between Mohs surgeries performed with non-sterile and sterile gloves [26, 27].

PPE guidelines need to consider the protection of the proceduralist from exposures to blood, tissue, and other bodily fluid. Such concerns may be more attributable to procedures involving high-pressure systems (such as arterial access) in which fluid splashes may be more common. For example, in a series of 100 angiographic procedures, 23 blood splashes occurred during 7 procedures, and the authors concluded that while the risk was low, face and eye protection were warranted [28].

Considering rising healthcare costs and the production of approximately four billion pounds of medical waste annually in the USA, it behooves proceduralists to weigh the theoretical benefit of infection rate reduction by PPE with the costs, both financially and environmentally. Increased healthcare costs associated with more stringent requirements for operating room attire has been extensively published in the surgical literature [23, 25, 29,30,31,32,33]. The healthcare industry is estimated to be responsible for 8% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the USA [7]. A recent analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from a tertiary care interventional radiology service found that the production and transportation of single-use supplies, including personal protective equipment, accounted as the second largest contributor to emitted carbon dioxide from the service [8]. Not unexpectedly, the survey results showed increased PPE use during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Global shortages in PPE during the beginning of the pandemic further echo the need for prudent and judicious use of these medical resources [34]. Most PPE is designed as single use and intended to be subsequently disposed, but preservation strategies for decontamination and reuse of PPE have been critical during supply shortages [35, 36]. These strategies may be useful for decreasing waste and cost when applied to CSIR procedures.

The survey also found that chlorhexidine agents are used by the vast majority of respondents for all procedures for skin site antisepsis, in keeping with the widespread adoption after superior performance of chlorhexidine-alcohol over povidone-iodine was demonstrated [37]. All respondents reported use of sterile towels and/or sterile paper drapes for all procedures.

There are several limitations to this study. This survey was sent to a subset of abdominal radiologists, the vast majority working in academic practices, and the observations may thus vary from other types of practice groups. Nonresponse bias may also affect the results, although members from 20 out of 22 institutions represented in the ETC completed the survey. Additionally, institutional and individual post-procedural infection rates were not assessed and therefore the true relationship between PPE and the risk of infection cannot be determined on the basis of this survey.

Further investigation is warranted to examine the appropriate level of PPE for CSIR procedures and elucidate the true role of PPE in protecting both the patient and proceduralist. Given the extremely low risk of infection and the wide range of current practices evident in the survey, prospective studies comparing procedures performed with and without certain types of PPE can be ethically conducted. Assessment of cost and waste reduction would also be necessary, as this information would be of interest to institutions seeking to reduce their carbon footprint or to maximize profits by decreasing costs.

In conclusion, this survey shows the variation of PPE practices among abdominal radiologists performing CSIR procedures. Considering the lack of strong evidence to support increased PPE use and the financial and environmental impact, it is time to re-examine the theoretical but not proven benefit of PPE in CSIR procedural settings and establish consensus standards.

References

Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, Harbrecht BG, Jensen EH, Fry DE, Itani KMF, Dellinger EP, Ko CY, Duane TM (2017) American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, 2016 Update. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 224:59–74 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029

Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Greene L, Nyquist A-C, Saiman L, Yokoe DS, Maragakis LL, Kaye KS (2014) Strategies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 35:605–627 . https://doi.org/10.1086/676022

Bartek M, Verdial F, Dellinger EP (2017) Naked Surgeons? The Debate About What to Wear in the Operating Room. Clinical Infectious Diseases 65:1589–1592 . https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix498

Salassa TE, Swiontkowski MF (2014) Surgical Attire and the Operating Room: Role in Infection Prevention. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 96:1485–1492 . https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.01133

McHugh SM, Corrigan MA, Hill ADK, Humphreys H (2014) Surgical attire, practices and their perception in the prevention of surgical site infection. The Surgeon 12:47–52 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2013.10.006

Chan D, Downing D, Keough CE, Saad WA, Annamalai G, d’Othee BJ, Ganguli S, Itkin M, Kalva SP, Khan AA, Krishnamurthy V, Nikolic B, Owens CA, Postoak D, Roberts AC, Rose SC, Sacks D, Siddiqi NH, Swan TL, Thornton RH, Towbin R, Wallace MJ, Walker TG, Wojak JC, Wardrope RR, Cardella JF (2012) Joint Practice Guideline for Sterile Technique during Vascular and Interventional Radiology Procedures: From the Society of Interventional Radiology, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, and Association for Radiologic and Imaging Nursing, for the Society of Interventional Radiology (Wael Saad, MD, Chair), Standards of Practice Committee, and Endorsed by the Cardiovascular Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 23:1603–1612 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2012.07.017

Eckelman MJ, Sherman J (2016) Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS One 11:e0157014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157014

Chua ALB, Amin R, Zhang J, Thiel CL, Gross JS (2021) The Environmental Impact of Interventional Radiology: An Evaluation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from an Academic Interventional Radiology Practice. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 32:907-915.e3 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2021.03.531

(2016) AIUM Practice Parameter for the Performance of Selected Ultrasound-Guided Procedures. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 35:1–40. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2016.35.9.5

Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD (2009) Liver biopsy. Hepatology 49:1017–1044 . https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22742

Lee YH, Baek JH, Jung SL, Kwak JY, Kim J, Shin JH, Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology (KSThR), Korean Society of Radiology (2015) Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration of Thyroid Nodules: A Consensus Statement by the Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology. Korean J Radiol 16:391 . https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2015.16.2.391

Luciano RL, Moeckel GW (2019) Update on the Native Kidney Biopsy: Core Curriculum 2019. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 73:404–415 . https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.011

Lorentzen T, Nolsøe C, Ewertsen C, Nielsen M, Leen E, Havre R, Gritzmann N, Brkljacic B, Nürnberg D, Kabaalioglu A, Strobel D, Jenssen C, Piscaglia F, Gilja O, Sidhu P, Dietrich C (2015) EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part I. Ultraschall in Med 36:E3–E16 . https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1553593

Reddy P, Liebovitz D, Chrisman H, Nemcek AA, Noskin GA (2009) Infection Control Practices among Interventional Radiologists: Results of an Online Survey. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 20:1070-1074.e5 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.071

Cervini P, Hesley GK, Thompson RL, Sampathkumar P, Knudsen JM (2010) Incidence of Infectious Complications After an Ultrasound-Guided Intervention. American Journal of Roentgenology 195:846–850 . https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.09.3168

Knott EA, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lubner SJ, Swietlik JF, Weber SM, Zlevor AM, Longhurst C, Hinshaw JL, Lubner MG, Mulkerin DL, Abbott DE, Deming D, LoConte NK, Uboha N, Couillard AB, Wells SA, Laeseke PF, Alexander ML, Lee Jr FT (2021) Microwave ablation for colorectal cancer metastasis to the liver: a single-center retrospective analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol 12:1454–1469. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo-21-159

Klapperich ME, Abel EJ, Ziemlewicz TJ, Best S, Lubner MG, Nakada SY, Hinshaw JL, Brace CL, Lee FT, Wells SA (2017) Effect of Tumor Complexity and Technique on Efficacy and Complications after Percutaneous Microwave Ablation of Stage T1a Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Center, Retrospective Study. Radiology 284:272–280 . https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016160592

Atwell TD, Farrell MA, Leibovich BC, Callstrom MR, Chow GK, Blute ML, Charboneau JW (2008) Percutaneous Renal Cryoablation: Experience Treating 115 Tumors. Journal of Urology 179:2136–2141 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.144

Welch BT, Schmitz JJ, Atwell TD, McGauvran AM, Kurup AN, Callstrom MR, Schmit GD (2017) Evaluation of infectious complications following percutaneous liver ablation in patients with bilioenteric anastomoses. Abdom Radiol 42:1579–1582 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-017-1051-5

Larson AM, Chan GC, Wartelle CF, McVicar JP, Carithers RL, Hamill GM, Kowdley KV (1997) Infection complicating percutaneous liver biopsy in liver transplant recipients. Hepatology 26:1406–1409 . https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510260605

Committee of Practical Guide for Kidney Biopsy 2019, Kawaguchi T, Nagasawsa T, Tsuruya K, Miura K, Katsuno T, Morikawa T, Ishikawa E, Ogura M, Matsumura H, Kurayama R, Matsumoto S, Marui Y, Hara S, Maruyama S, Narita I, Okada H, Ubara Y (2020) A nationwide survey on clinical practice patterns and bleeding complications of percutaneous native kidney biopsy in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol 24:389–401 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-020-01869-w

Peters B, Giuffre JL (2018) Canadian Trends in Carpal Tunnel Surgery. The Journal of Hand Surgery 43:1035.e1-1035.e8 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.02.014

Yu J, Ji TA, Craig M, McKee D, Lalonde DH (2019) Evidence-based Sterility: The Evolving Role of Field Sterility in Skin and Minor Hand Surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open, 7(11), e2481. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002481

LeBlanc MR, Lalonde DH, Thoma A, Bell M, Wells N, Allen M, Chang P, McKee D, Lalonde J (2011) Is main operating room sterility really necessary in carpal tunnel surgery? A multicenter prospective study of minor procedure room field sterility surgery. Hand (New York, N.Y.), 6(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-010-9301-9

Stephens AR, Tyser AR, Presson AP, Orleans B, Wang AA, Hutchinson DT, Kazmers NH (2021) A Comparison of Open Carpal Tunnel Release Outcomes Between Procedure Room and Operating Room Settings. J Hand Surg Glob Online 3:12–16 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.10.009

Kemp DM, Weingarten S, Chervoneva I, Marley W (2019) Can Nonsterile Gloves for Dermatologic Procedures Be Cost-Effective without Compromising Infection Rates? Skinmed 17:155–159

Mehta D, Chambers N, Adams B, Gloster H (2014) Comparison of the Prevalence of Surgical Site Infection with Use of Sterile Versus Nonsterile Gloves for Resection and Reconstruction During Mohs Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.], 40(3), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsu.12438

McWilliams RG, Blanshard KS (1994) The risk of blood splash contamination during angiography. Clinical Radiology 49:59–60 . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9260(05)82917-4

Stapleton EJ, Frane N, Lentz JM, Armellino D, Kohn N, Linton R, Bitterman AD (2020) Association of Disposable Perioperative Jackets With Surgical Site Infections in a Large Multicenter Health Care Organization. JAMA Surg 155:15 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4085

Elmously A, Gray KD, Michelassi F, Afaneh C, Kluger MD, Salemi A, Watkins AC, Pomp A (2019) Operating Room Attire Policy and Healthcare Cost: Favoring Evidence over Action for Prevention of Surgical Site Infections. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 228:98–106 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.010

Wang JV, Do RDM, Bs NJ, Rohrer T, Saedi N. Sterility and cost of gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: Sterile or peril? Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 19(9), 2384–2385. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13422

Kazmers NH, Stephens AR, Presson AP, Yu Z, Tyser AR (2019) Cost Implications of Varying the Surgical Setting and Anesthesia Type for Trigger Finger Release Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7:e2231 . https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002231

Nuzzi LC, Taghinia A Surgical Site Infection After Skin Excisions in Children: Is Field Sterility Sufficient? Pediatric dermatology, 33(2), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12523

Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M (2020) Sourcing Personal Protective Equipment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 323:1912 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317

Wormer BA, Augenstein VA, Carpenter CL, Burton PV, Yokeley WT, Prabhu AS, Harris B, Norton S, Klima DA, Lincourt AE, Heniford BT (2013) The green operating room: simple changes to reduce cost and our carbon footprint. Am Surg 79:666–671

Grant K, Andruchow JE, Conly J, Lee DD, Mazurik L, Atkinson P, Lang E (2021) Personal protective equipment preservation strategies in the covid-19 era: A narrative review. Infection Prevention in Practice 3:100146 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2021.100146

Darouiche RO, Otterson MF, Miller HJ, Mosier MC (2010) Chlorhexidine–Alcohol versus Povidone–Iodine for Surgical-Site Antisepsis. The New England journal of medicine, 362(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810988

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Planz, V., Huang, J., Galgano, S.J. et al. Variability in personal protective equipment in cross-sectional interventional abdominal radiology practices. Abdom Radiol 47, 1167–1176 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-021-03406-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-021-03406-z