Abstract

Accurate diagnosis, monitoring and treatment decisions in patients with chronic liver disease currently rely on biopsy as the diagnostic gold standard, and this has constrained early detection and management of diseases that are both varied and can be concurrent. Recent developments in multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) suggest real potential to bridge the diagnostic gap between non-specific blood-based biomarkers and invasive and variable histological diagnosis. This has implications for the clinical care and treatment pathway in a number of chronic liver diseases, such as haemochromatosis, steatohepatitis and autoimmune or viral hepatitis. Here we review the relevant MRI techniques in clinical use and their limitations and describe recent potential applications in various liver diseases. We exemplify case studies that highlight how these techniques can improve clinical practice. These techniques could allow clinicians to increase their arsenals available to utilise on patients and direct appropriate treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic liver disease leads to progressive injury from various aetiologies such as: iron overload, steatosis, steatohepatitis, viral hepatitis, autoimmune, metabolic disease and some drug toxicities. These represent the majority of aetiologies of liver diseases and vary in estimated worldwide prevalence so that of 112 million prevalent cases of compensated cirrhosis reported in 2017, 36 million were due to hepatitis B, 23 million from alcoholic liver disease and 4 million from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [1].

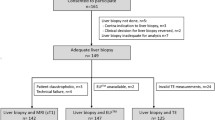

In recent clinical practice, the number of referrals for abdominal and liver magnetic resonance (MR), including focussed liver MRI for diffuse disease, has increased. In part this is because tools used in current clinical practice for the diagnosis of liver disease have intrinsic limitations. Screening, monitoring and therapy decision-making abilities of multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) are being increasingly recognised by hepatologists and gastroenterologists. Liver biopsy on the other hand is invasive, associated with potential complications [2,3,4] and subject to variability in sampling and interpretation [5,6,7]. Serum biomarkers are widely available but are non-specific [8,9,10,11]. Transient elastography (TE) and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) are available in many practices as point of care to assess elasticity of the liver and steatosis, respectively, but are limited by high measurement failure rates especially in obese patients [12,13,14,15,16]. New methods and standardisation of imaging protocols have allowed radiologists to quantify features of liver parenchyma and alter practice and decision-making, although this is not yet fully reflected in clinical guidelines.

Current clinical guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) do not recommend routine screening for steatosis, even in high-risk groups in primary care, diabetes, or obesity clinics [17]. Instead NAFLD guidelines emphasise stratification of patients into those at low and high risk of fibrosis, with diagnosis based on the use of specific serum biomarkers and elastography-based techniques [17,18]. Liver biopsy is recommended in patients at higher risk of steatohepatitis or advanced fibrosis, or cirrhosis, to confirm diagnosis or to clarify disease aetiology [17]. Nevertheless, guidelines for diabetes management recommend diagnostic procedures to assess the degree of NAFLD or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) irrespective of liver enzyme levels, due to the high risk of liver disease progression in this patient population [19,20]. In autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), clinical guidelines recommend a combination of blood tests and biopsy to assess response to pharmacotherapy and monitor resolution of histological inflammation [21]. This can lead to disease mismanagement or complications for the patient that an imaging test has the potential to avoid. In genetic haemochromatosis, the guidelines centre around early detection and monitoring via blood tests and confirmation, if necessary, with biopsy [22].

The needs of payers, clinicians and healthcare systems that support patients through disease progression and prevention, however, go beyond the existing guidelines and highlight diagnostic gaps. The needs in the management of chronic liver disease are largely dictated by costs and availability of treatment options. Academic and real-world community clinical management varies due to availability of resources, with community clinicians less likely to follow guidelines or monitor patients frequently [23,24]. In outpatient clinics, differentiation of steatosis from steatohepatitis to identify severe disease in alcoholic liver disease, NAFLD or both (BAFLD) is extremely vital in the management of these patients [25]. In AIH and haemochromatosis early diagnosis and monitoring response to disease treatment is important. In addition, recent developments in our understanding of liver disease, in light of increased epidemics of obesity and autoimmunity, have increased the impact of chronic liver disease in related clinical care pathways, for metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [26], for example. This places additional pressure on an already overloaded healthcare system but may be transformed by additional diagnostic tools, especially as the maturation of new pharmacotherapies in steatohepatitis and diabetes could introduce new treatment and diagnostic opportunities.

Recent developments suggest that mpMRI could bridge some of these diagnostic gaps, the biggest impact being to obviate the need for histological assessment of disease activity and staging via liver biopsy in many clinical disease states [22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. It is only a matter of time before liver mpMRI enables clinical practice transformation, following in the footsteps of success stories already seen in breast cancer, prostate cancer and cardiology [37,38,39]. Here we review some of the parametric MRI techniques in clinical use that underpin mpMRI, as well as some of their potential clinical limitations and describe recent potential applications in patients with chronic liver disease.

mpMRI methods in clinical practice

Multiparametric MRI refers to use of multiple quantitative (parametric) MRI features or measures with several possibilities for combinations [34,35,36,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Therefore, these combinations could be used to evaluate two or more specific characteristics of chronic liver disease and diffuse liver processes, to include derivation of composite metrics [44,46]. We will limit this review to parametric MRI techniques in clinical decision-making for chronic liver disease that are available to the practicing radiologist. For example, T1rho is an exciting approach that explores a relaxation due to low frequency (kHz) exchange interactions and may find utility once it has been validated and deployed at scale [47], SWI (susceptibility weighted imaging) provides an approach for measuring local magnetic susceptibility that can assess fibrosis [41] and has been shown to be affected by iron, fat and collagen deposition [41,48,49]. Developments utilising contrast agents are not included, as these have been reviewed recently elsewhere [50] and are mainly used in characterisation of hepatocellular lesions and carcinomas.

-

T2/T2*: Since R2 = 1/T2 and R2* = 1/T2*, we will talk about them indiscriminately. Iron content can be measured using spin-density projection-assisted R2 [51,52] or T2* transverse relaxation, for example with GRE sequences [16,28,40,53]. These methods are standardised across scanners [42,51] and commercially available (Resonance Health, Australia and Perspectum, UK, respectively). Semi-automated post-processing services with same day turnarounds are now possible for T2*. Fibrosis, fat, and other hepatic cellular pathology contribute to R2 and R2* and interfere with liver iron content estimation [54,55,56]. The effect of fat has accuracy implications in NAFLD [55] but appears to be relatively small and may be minimised by mathematical correction [57,58]. In, addition, R2* can be obtained simultaneously with PDFF with Dixon-based sequences [55,56,59]. The confounding effect of fibrosis may be overcome with newer processing methods [54].

-

Proton density fat fraction (PDFF): PDFF is a ratio, expressed as a percentage, of the fraction of the MRI-visible protons attributable to fat divided by all MRI-visible protons in that region of the liver attributable to fat and water. Taking advantage of the chemical shift between fat and water, pulse sequences can be used to acquire images at multiple echo times at which fat and water signals have different phases relative to each other [60, 61]. PDFF can be performed with very high precision using a multiple echo spoiled GRE sequence with > 3 echo times. To avoid biasing the PDFF measurement it is important to image with a low flip angle to minimise T1 weighting (such as flip angle 5°, TR = 12 ms at 1.5T,flip angle 3°, TR = 14 ms at 3T) [62]. A complete set of sequence recommendations has been formulated by the quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance group (QIBA) [63,64]. MRI-PDFF is easier to perform, has high reproducibility [65, 59, 64] and reflects fat distribution on at least one cross-sectional slice rather than a few voxels, so has replaced measurement of triglyceride content using 1H MR spectroscopy even in guideline recommendations [17, 66] including for diabetes [19]. To minimise T1 bias (fat has shorter T1 than water), a low flip angle is used, along with acquisition or algorithmic corrections for T2* effects [59,67,68,69]. Developments in echo times [70,71,72] and processing improve sensitivity to field inhomogeneities, signal-to-noise ratios and sensitivity at PDFF > 50% [73,74]. These also highlight that PDFF accuracy is not meaningfully confounded by any of age, sex, BMI, inflammation or fibrosis [75,76].

-

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE): MRE uses low frequency mechanical shear waves to cause liver vibrations that are detected by MRI, based on a modified phase contrast pulse sequence [34, 77]. 3D-MRE takes advantage of additional spin-echo echo-planar-imaging (SE-EPI) to capture shear wave displacements along three dimensions, and images the entire liver rather than regions of interest (ROI) but to date is not FDA-cleared [78,79]. MRE is commercially available on 1.5T and 3T MRI scanners once suitable hardware is added in order to produce the requisite mechanical waves, and once specific software is installed for elastogram acquisition (Resoundant Inc., USA). Standardisation of 2D-MRE exists on three major vendors [80,81], although different shear wave frequencies are used outside the USA that are not FDA-cleared [82] and there is no consensus yet on the standards for ROI number, size or shape, which can add to measurement variability [83]. This could be overcome by dedicated freehand ROI selection under supervision of an experienced radiologist or by using additional software to aid in this process [84]. The accuracy of MRE for early fibrosis is reportedly superior to transient elastography (TE) but equivalent in cases of advanced fibrosis [34,85,86,87], and MRE shear waves may propagate through small- and medium-sized ascites. MRE has a lower measurement failure rate than TE and has reportedly better repeatability [88]. However, iron deposition in the liver is a reported confounder for MRE that is significantly associated with measurement failure [77]. MRE is confounded by even mild iron overload, necessitating mpMRI with T2, T2* or, more recently, SE-EPI sequences [35,89,90]. Additional measurement of PDFF to evaluate steatosis has been attempted alongside MRE [36,40], as PDFF and T2* can be acquired within a single breath-hold. As with TE, MRE values are affected by chronic and acute inflammation, which can cause overlap in elastography values of patients with no or mild fibrosis [9,91]. Thus, high liver stiffness values can be obtained without any degree of fibrosis, resulting in low positive predictive value.

-

T1/corrected T1 (cT1): Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) T1 maps provide diagnostic information in the heart, so that increased T1 can be diagnostic of oedema (increased tissue water) or increased interstitial space [92,93,94], whilst increased extracellular volume is a powerful independent predictor of mortality in patients with severe aortic stenosis [95]. Similarly, the T1 of the water component is of diagnostic significance in the liver using MOLLI mapping or inversion recovery echo-planar imaging readouts to characterise tissue [28,68,96,97,98]. Since iron is a ferromagnetic material, it can shorten tissue T1 and T2 relaxation times and this is further accentuated by the dependence of MOLLI T1 on T2 [99], with potential bias equivalent to one fibrosis stage when hepatic iron content increases from normal to high levels (1.0 to 2.5 mg/g) [100,101]. The confounding effect of iron on T1 mapping is corrected by a compensatory algorithm, based on the application of a multi-compartment model to simulate tissue and water environments in the liver during changes in iron content and in extracellular fluid (a proxy for fibrosis) [100]. For simplification the resulting cT1 is treated as a parametric component in this review, despite requiring T2* measurement. cT1 is commercially available as post-processing software (with T2* and PDFF, LiverMultiScan™, Perspectum, UK) and correlates with parenchymal fibrosis, inflammation and ballooning [16,28,31,32,76,102]. cT1 shows low measurement failure rates, high repeatability and reproducibility that are superior to those of elastography techniques in both published and preliminary data [42,80,88]. Fat has some additive effect on MOLLI T1 measurements at 3T [103] and by extension on cT1, but optimisation of MOLLI sequence parameters may be used to manage these biases, for example by use of asymmetric echo times during bSSFP [104]. Correlation of cT1 with histological disease features is maintained even after controlling for steatosis [76].

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): Quantitative measures of diffusion can be produced by measuring the magnitude (apparent diffusion coefficient; ADC) and directionality (fractional anisotropy) of diffusion. The accumulation of steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis can lead to changes in water diffusion and these can be measured using various DWI techniques. Whilst mainly applied clinically in focal lesion characterisation, recent developments have potential utility in viral hepatitis and staging fibrosis [105,106,107,108,109,110]. Limitations include lack of standardisation with inconsistencies reported for field strength [111] and B values [112,113]. Imaging homogeneity artefacts can be improved with simultaneous multi-slice respiratory-triggered acceleration (SMS-RT-DWI) [114]. Another DWI approach with promise is IVIM (intravoxel incoherent motion) that utilises diffusion imaging methods to explore both microcirculatory water motions and diffusion. Although specialist processing tools are required, recent studies indicate IVIM may further enhance fibrosis staging but this requires validation beyond focal disease [115,116,117,118].

Commercially available methodologies used in clinical practice differ in their performance and applicability to different MR scanner systems, with particular consequences in terms of operability (Table 1). Below we will describe how these techniques can be used for diagnosis, monitoring, and predicting outcomes—we will describe these in frequently occurring hepatology problems encountered in clinical care, with examples.

Applications of mpMRI in chronic liver disease

Haemochromatosis

The proper staging of patients with genetic heamochromatosis (HFE) is paramount for treatment. The ability to use MRI to quantify liver iron concentration and the presence of non-invasive serologic markers for fibrosis prediction (serum ferritin, platelets, transaminases), have diminished the diagnostic need for biopsy in haemochromatosis. Genetic testing is required to differentiate true genetic hemochromatosis (homozygous C282Y) from the other forms of milder hemochromatosis or even secondary iron overload syndromes [22,119]. Recent studies have identified elevated iron without homozygosity for the p.C282Y variant in the HFE gene, highlighting the continued undetected disease existing in the general population [120,121,122]. Increased iron can be co-existing in NAFLD, ALD and other chronic liver diseases [22,122,123]. Elevated liver iron has been reported in NALFD cohorts at prevalence that ranges between 10–34.5%, based on histochemical staining [40,102,124,125,126]. Both R2 and T2* based imaging could therefore be used clinically if integrated into clinical guidelines to identify such cases. Additional clinical applications for R2 and T2* are reviewed extensively by Wood [127].

Foci of increased iron occur in the regenerating nodules surrounded by fibrosis in cirrhotic livers [128]. The development of fibrosis and liver cirrhosis changes both the prognosis and the management of haemochromatosis, especially as patients improve after treatment with phlebotomy and show liver fibrosis regression [22]. Detection of fibrosis through cT1 or TE is preferable to MRE in these cases due to the confounding effect of iron resulting in MRE technical failures [77].

Steatohepatitis (NASH/ASH)

Alcohol acts synergistically with obesity and diabetes in the progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [93], patients with both NAFLD and ALD have more advanced fibrosis compared to those with NAFLD alone [25]. Indeed, steatohepatitis from both NAFLD and ALD is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and outcomes than either NASH or ASH alone [129, 130]. Hepatic fibrosis has been shown to predict patient mortality [131], so clinicians have relied on elastographic techniques to evaluate severity and make appropriate decisions.[78]. However, other histological features contribute to steatohepatitis, such as inflammation and ballooning, collectively known as disease activity [17]; steatohepatitis is defined as the presence of 5% steatosis with inflammation and hepatocyte injury (e.g. ballooning), with or without any degree of fibrosis. Most of these tissue characteristics may be detected as an increase in T1 relaxation time [31,96,98].

Diagnosis

The diagnostic accuracy, linearity and precision of PDFF has been validated in many studies, showing that PDFF assessments closely correlate with steatosis assessment based on liver biopsy, magnetic resonance spectroscopy and chemical analysis of tissue samples [30,64,132]. However, PDFF cannot differentiate simple steatosis (NAFL) from steatohepatitis (NASH) necessitating other measurements to identify disease activity and fibrosis. cT1 has been used to improve stratification of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the general population [133], in patients with co-prevalent type 2 diabetes [134] and from other parenchymal disease [102], whilst MRE can also discriminate healthy from NAFLD individuals [135]. Thus, radiology could enable earlier detection of disease before increased severity or fibrosis develop.

The diagnostic accuracy of fibrosis using cT1 is either equivalent or inferior to diagnosis by elastography based on comparative studies in NAFLD-only cohorts, with equivalent AUROC of 0.83 reported for cT1-based diagnosis of NASH or significant fibrosis in predominantly NAFLD cohorts as published and preliminary data indicate [32,85,102]. This may reflect the relatively small percent change in collagen percentage area that differentiates between stages of fibrosis [7], especially as mouse models of liver fibrosis have demonstrated that T1 and T2∗ correlations to fibrotic disease severity vary with aetiology [136]. Accuracy improves when cT1 is applied as a composite biomarker with blood biomarkers (AUROC of 0.84–0.97 are reported for detection of NASH with significant fibrosis, as published and preliminary data indicate [46,137]).

Using MRE, the accuracy of diagnosis of fibrosis (AUROC of 0.84–0.93 reported, depending on the fibrosis stage) is better than for identification of NASH only (AUROC of 0.58–0.73), although higher accuracy has been reported in mainly fibrotic NASH cohorts [34,82,85,87,135,138,139]. 3D-MRE was shown to be superior to 2D-MRE for advanced fibrosis and equivalent for NASH [78]. MRE is recommended for identifying patients who are at risk for steatohepatitis and/or advanced fibrosis in guidelines.

Conversely, cT1 is superior to MRE in stratification of NASH as shown in NAFLD cohorts in the UK, US and Japan, as preliminary data show [140,141]. In NAFLD cohorts cT1 strongly correlated with NAFLD activity score [102] and ballooning [32], with an AUROC of 0.84 for diagnosis so it may have utility in earlier detection and diagnosis of disease activity. Limited correlation to lobular inflammation has been observed in NALFD cohorts [16,32,76,102], although moderate to severe inflammation significantly increased T1 independently from fibrosis, using cT1 (or echoplanar imaging [96] in cohorts of chronic liver disease of mixed aetiologies [28]. This may reflect the low grade inflammation seen in NAFLD [142]. Use of cT1 to confirm disease in patients with suspected NAFLD may be financially advantageous as a result of reducing the need for further confirmatory diagnostics such as liver biopsy in UK and European clinical care published and preliminary data show [29,102,134]. Fat droplets in NASH cause changes to the liver parenchyma including oxidative stress, activation of cytokines resulting in local inflammation and eventual collagen deposition [143]. Such effects could also affect the amount of extracellular water and free water diffusion and have been investigated with DWI [110,115]. Emerging research on the derivation of ADC and IVIM signals suggests that microcirculation in vessels (perfusion) rather than molecular diffusion within liver tissue may correlate with histological staging of liver fibrosis [115]. Standardisation of the acquisition protocols, based on respiratory-triggered fat-saturated spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequences, would serve to validate these findings, with potential application in diagnosis of inflammation.

Monitoring

Until now there have been no licensed pharmaceutical therapies for the NAFLD spectrum and, despite the difficulty of patient adherence to lifestyle changes, diet and exercise have been the first-line recommendations. Bariatric surgery is available for morbidly obese patients with steatohepatitis and can be monitored by PDFF, MRE or cT1 [36] (Fig. 1). However, not all patients are candidates for surgery. Clinical practice will likely change due to the encouraging interim results of a phase 3 study with obeticholic acid in reducing fibrosis [144], and other phase 3 trials affecting hepatic metabolism, or acting as anti-inflammatory or anti-fibrotics [145]. MRI is critical in clinical trials for NASH, with PDFF and cT1 being used as primary endpoints and MRE as a secondary endpoint in both published and preliminary findings [146,147]. A recent study of a chemical inhibitor of de novo lipogenesis, GS-0976, improved outcomes in NASH patients and reduced PDFF but no substantial change was detected using MRE [148].

Diagnosis of complications and predicting outcomes

Both PDFF and cT1 are significantly higher in patients with type 2 diabetes [149,150] and a positive correlation between MOLLI T1 values in the liver and history of cardiovascular disease has been reported in a large multi-ethnic, adult population study spanning over 10 years [151]. In a smaller study MRE confirmed the association between fibrosis and increased cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes [152]. cT1 can be used to predict liver-related clinical outcomes (such as ascites, encephalopathy, liver-related mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma) with 100% negative predictive value [31] and as accurately as biopsy [153] in patients with ASH, NASH or viral hepatitis. cT1 can also be used to predict liver event-free survival as emerging data indicate [154,155]. cT1 has reported application in detecting portal hypertension as published and preliminary data indicate [156,157,158] and MRE in predicting variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients [159, 160]. Both technologies could provide additional value in prediction of liver-related outcomes of patients after hepatic resection or transplantation.

Paediatric disease

Histopathological features of NAFLD in children may differ from those in adults, particularly in younger children in whom steatosis may be more abundant or accentuated in different zones. Inflammation and fibrosis may be concentrated in portal tracts initially rather than the traditional pericentral seen in adults and ballooning is less frequent as well. The presence of significant steatosis or inflammation in a biopsy-confirmed fibrotic cohort spanning infants to young adults resulted in a significant reduction in MRE sensitivity [161]. AUROC for significant fibrosis dropped from 0.82 to 0.53 in the presence of steatosis [161], whilst in contrast data with cT1 confirms that higher disease activity is present with increasing obesity in emerging data [162] (Fig. 2). As with adults cT1 in paediatrics has high repeatability and reproducibility [163] and correlates with histological scoring of ballooning, fibrosis, and both portal and lobular inflammation [164], as suggested by preliminary data.

Viral hepatitis

Clinicians can stage fibrosis and level of inflammation with MRE or cT1 [28,31,102] and monitor effect of treatment [165], which is important to know prior to therapy decision-making for Hep C and Hep B. (Fig. 3). Compared to steatohepatitis, viral disease results in higher incidence of cirrhosis. Elevated T1 in the liver has been associated with increasing severity of cirrhosis using modified respiratory-triggered inversion-recovery sequences [98]. High T1 values could stratify compensated cirrhosis from decompensated cirrhosis and were associated with and predictive of liver disease outcomes in patients with compensated cirrhosis [98]. In addition, DWI, in particular IVIM, could stratify patients with viral hepatitis in terms of fibrosis [109,115,166] and inflammation [105,110,116], with recent publications discriminating cirrhotic livers from healthy livers [107,116] and stratifying disease severity based on blood biomarker scoring systems [106] or TE [167]. DWI also attains high accuracy for identification of oesophageal and gastric fundic varices [107]. However, as TE is more scalable in the developing world this is a more frequent diagnostic solution.

Autoimmune liver disease (AIH, cholangitis)

AIH is a disease associated with the production of autoantibodies (ANA, SMA), resulting in chronic inflammation and, if untreated, fibrosis and cirrhosis over time [168]. AIH patients tend to experience disease flares throughout their life span. Patients require life-long monitoring to evaluate response to treatment options, such as corticosteroids and azathioprine among others [21]. Biochemical remission is often challenging, and only 38–93% of patients are able to achieve a complete histological response [169]. Up to 50% of patients develop cirrhosis while undergoing treatment despite [170] having normal biochemical markers [171].

Diagnosis

cT1 is more sensitive to subtle changes in inflammation in the liver than circulating biomarkers and elastography, as published and preliminary data show [172,173,174,175]. This supports the ability of cT1 to measure liver inflammation without steatosis [172,173,174,175]. High AUROC for detection of advanced fibrosis have been reported in patients with AIH, using MRE [176] or DWI [109]. Additionally, as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) can be co-prevalent with AIH, cT1 can be used to differentiate between patients with AIH and biliary disease as emerging data show [177]. Furthermore, these patients may benefit from additional characterisation with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) [178] or DWI [167], including with recently developed software to enhance and quantitate MRCP images (MRCP+, Perspectum, UK) [179,180]. Additionally, cT1, MRE and DWI have reported application in detecting portal hypertension in such cohorts, with highest AUROC reported for MRE [157].

Monitoring

Improvements on immunosuppressive treatment (elevated baseline returning to normal levels at follow-up) have been detected by cT1 in AIH, and cT1 discriminates between treatment-naive AIH patients and those post-treatment, as published and emerging data show [173,181,182]. cT1 can be used to predict clinical outcomes (AUROC for future flare events 0.721, p = 0.003) better than TE (AUROC: 0.502, p = 0.983) and the enhanced liver fibrosis test (AUROC: 0.501, p = 0.992), indicated by emerging data [174,182,183]. Subtle changes in disease heterogeneity can also be quantified by cT1, as the interquartile range (IQR) (Fig. 4).

Paediatric disease

In paediatric populations cT1 has shown significant correlations with ballooning, fibrosis and inflammation in emerging data [164,182,184]. When combined with circulating biomarkers, cT1 can predict flares in paediatric AIH with a specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 50% (PPV 100%, NPV 57%) [183]. Moreover, cT1 can be used to stratify patients with AIH from those with other liver diseases including Wilson’s disease in emerging data [183,185,186,187] (Fig. 5), thus suggesting a wide range of potential utilities. This stratification is further improved when cT1 is used as a composite biomarker with PDFF in these studies [181].

Conclusion

The studies described here demonstrate that high accuracy can be obtained by application of an array of MRI techniques in clinical care. MRE supports stratification of fibrosis as a window to disease state, cT1 is diagnostic of disease activity and progression whilst iron content can be quantified by (reciprocal) transverse relaxation. These techniques have the potential to influence American College of Radiology guidelines and to complement existing diagnostics, enabling clinicians to diagnose, stratify and monitor liver disease earlier and with greater confidence. In particular, improved monitoring of response to new and existing treatments may also be possible for a variety of liver diseases. This may reduce the reliance on invasive liver biopsy and improve patient experience and outcomes.

References

Collaborators GBD 2017 C (2020) The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 5 (3): 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8

Kim K, Ko G, Sung K et al. (2008) Transjugular liver biopsy in patients with living donor liver transplantation: comparison with percutaneous biopsy. Liver Transplantation 14 (7): 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.21448

Kalambokis G, Manousou P, Vibhakorn S et al. (2007) Transjugular liver biopsy- Indications, adequacy, quality of specimens, and complications - a systematic review. Journal of Hepatology 47 (2): 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2007.05.001

West J, Card TR (2010) Reduced mortality rates following elective percutaneous liver biopsies. Gastroenterology 139 (4): 1230–1237. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.015

Goodman Z (2007) Grading and staging systems for inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology 47 (4): 598–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.006

Kleiner D, Brunt E, Van Natta M et al. (2005) Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41 (6): 1313–1321. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20701

Standish RA, Cholongitas E, Dhillon A et al. (2006) An appraisal of the histopathological assessment of liver fibrosis. Gut 55 (4): 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.084475

Chin JL, Pavlides M, Moolla A, Ryan JD (2016) Non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis: adjuncts or alternatives to liver biopsy? Frontiers in Pharmacology 7 159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00159

Tapper E, Lok A (2017) Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 377 (8): 756–768.

Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K et al. (2009) Use of the FIB4 index for non-invasive evaluation of fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 7 (10): 1104–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.033

European Association for Study of Liver; Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado (2015) EASL-ALEH clinical practice guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. Journal of Hepatololgy 63 (1): 237–264.

Nascimbeni F, Lebray P, Fedchuk L et al. (2015) Significant variations in elastometry measurements made within short-term in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 13 (4): 763-771.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.037

Cast́era L, Foucher J, Bernard PH et al. (2010) Pitfalls of liver stiffness measurement: a 5-year prospective study of 13,369 examinations. Hepatology 51 (3): 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23425

Myers R, Pomier-Layrargues G, Kirsch R et al. (2012) Feasibility and diagnostic performance of the FibroScan XL probe for liver stiffness measurement in overweight and obese patients. Hepatology 55 (1): 199–208.

de Lédinghen V, Vergniol J, Capdepont M et al. (2014) Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) for the diagnosis of steatosis: a prospective study of 5323 examinations. Journal of Hepatology 60 (5): 1026–1031.

McDonald N, Eddowes P, Hodson J et al. (2018) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for quantitation of liver disease: a two-centre cross-sectional observational study. Scientific Reports 8 (1): 9189.

Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine J et al. (2018) The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 67 (1): 328–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29367

NICE (2016) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng49/chapter/recommendations. Accessed: June 2020.

American Diabetes Association (2020) Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 43 (Supplement 1): S37–S47. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S004

EASL, EASD & EASO (2016) EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obesity Facts 9 (2): 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443344

European Association for the Study of the Liver (2015) EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. Journal of Hepatololgy 63 (4): 971–1004.

Fitzsimons EJ, Cullis JO, Thomas DW et al. (2018) Diagnosis and therapy of genetic haemochromatosis (review and 2017 update). British Journal of Haematology 181 (3): 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15164.

Lee H, Ahn J, Kim W et al. (2019) A comparison between community and academic practices in the USA in the management of chronic hepatitis B patients receiving entecavir: results of the ENUMERATE study. Dig Dis Sci 64 (2): 358–366.

Thomson MJ, Tapper EB, Lok ASF (2018) Dos and Don’ts in the Management of Cirrhosis: A View from the 21st Century. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 113 (7): 927–931. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0028-5

Khoudari G, Singh A, Noureddin M et al. (201https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i10.7109) Characterization of patients with both alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a large United States cohort. World Journal of Hepatology 11 (10): 710–718.

Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J et al. (2020) MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 158 (7): 1999-2014.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312

Karlsson M, Ekstedt M, Dahlström N et al. (2019) Liver R2* is affected by both iron and fat: A dual biopsy-validated study of chronic liver disease. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 50 (1): 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26601

Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM et al. (2014) Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease. Journal of Hepatology 60 (1): 69–77.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.002

Blake L, Duarte R V, Cummins C (2016) Decision analytic model of the diagnostic pathways for patients with suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using non-invasive transient elastography and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. BMJ Open 6 (9): e010507. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010507

Hong CW, Mamidipalli A, Hooker JC et al. (2018) MRI proton density fat fraction is robust across the biologically plausible range of triglyceride spectra in adults with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 47 (4): 995–1002.https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25845

Pavlides M, Banerjee R, Sellwood J et al. (2016) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging predicts clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. Journal of Hepatology 64 (2): 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.009

Pavlides M, Banerjee R, Tunnicliffe EM et al. (2017) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease severity. Liver International 37 (7): 1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13284

Stoopen-Rometti M, Encinas-Escobar E, Ramirez-Carmona C et al. (2017) Diagnosis and quantification of fibrosis, steatosis, and hepatic siderosis through multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 82 (1): 32–45.

Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y et al. (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging more accurately classifies steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease than transient elastography. Gastroenterology 150 (3): 626-637.e7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.048

Cunha G, Villela-Nogueira C, Bergman A, Lobo Lopes F (2018) Abbreviated mpMRI protocol for diffuse liver disease: a practical approach for evaluation and follow-up of NAFLD. Abdom Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1504-5

Allen AM, Shah VH, Therneau TM et al. (2019) Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Elastography Improves the Detection of NASH Regression Following Bariatric Surgery. Hepatology Communications 4 (2): 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1446

Marino M, Helbich T, Baltzer P, Pinker-Domenig K (2018) Multiparametric MRI of the breast: a review. Journal Magnetic Resonance Imaging 47 (2): 301–315.

Bjurlin M, Carroll P, Eggener S et al. (2020) Update of the Standard Operating Procedure on the use of multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the diagnosis, staging and management of prostate cancer. Journal of Urology 203 (4): 706–712.https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000617

Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM et al. (2017) Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2* and extracellular volume: a consensus statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imagi. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 19 (1): 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-017-0389-8

Kühn J-P, Meffert P, Heske C et al. (2017) Prevalence of fatty liver disease and hepatic iron overload in a Northeastern German population by using quantitative MR imaging. Radiology 284 (3): 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017161228

Obmann VC, Marx C, Berzigotti A et al. (2019) Liver MRI susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) compared to T2* mapping in the presence of steatosis and fibrosis. European Journal of Radiology 118 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.07.001

Bachtiar V, Wilman H, Jacobs J et al. (2019) Reliability and reproducibility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the liver. PLOS ONE 14 (4): e0214921.

Lee Y, Yoo Y, Jung Y et al. (2020) Multiparametric MR is a valuable modality for evaluating disease severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 11 (4): e00157.

Kim JW, Lee Y-S, Park YS et al. (2020) Multiparametric MR Index for the Diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Scientific Reports 10 (1): 2671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59601-3

Obmann VC, Mertineit N, Marx C et al. (2019) Liver MR relaxometry at 3T - segmental normal T(1) and T(2)* values in patients without focal or diffuse liver disease and in patients with increased liver fat and elevated liver stiffness. Scientific Reports 9 (1): 8106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44377-y

Dennis A, Mouchti S, McKay A et al. (2020) Multi-parametric MRI as a composite biomarker with standard liver function tests for NASH with fibrosis. Scientific Reports submitted

Chen W, Chen X, Yang L et al. (2018) Quantitative assessment of liver function with whole-liver T1rho mapping at 3.0T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 46 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2017.10.009

Li, R. K., Zeng, M. S., Qiang, J. W., Palmer, S. L., Chen, F., Rao, S. X., Chen, L. L., & Dai YM (2017) Improving detection of iron deposition in cirrhotic liver using susceptibility-weighted imaging with emphasis on histopathological correlation. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 41 (1): 18–24.

Wei H, Decker K, Nguyen H et al. (2020) Imaging diamagnetic susceptibility of collagen in hepatic fibrosis using susceptibility tensor imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 83 (4): 1322–1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27995

Welle C, Guglielmo F, Venkatesh S (2020) MRI of the liver: choosing the right contrast agent. Abdominal Radiology 45 (2): 384–392.

St Pierre TG, El-Beshlawy A, Elalfy M et al. (2014) Multicenter validation of spin-density projection-assisted R2-MRI for the noninvasive measurement of liver iron concentration. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 71 (6): 2215–2223. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.24854

Lin H, Fu C, Kannengiesser S et al. (2018) Quantitative analysis of hepatic iron in patients suspected of coexisting iron overload and steatosis using multi-echo single-voxel magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Comparison with fat-saturated multi-echo gradient echo sequence. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 48 (1): 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25967

Siegelman E, Mitchell D, Semelka R (1996) Abdominal iron deposition: metabolism, MR findings, and clinical importance. Radiology 199 (1): 13–22.

Li J, Lin H, Liu T et al. (2018) Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) minimizes interference from cellular pathology in R2* estimation of liver iron concentration. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 48 (4): 1069–1079. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26019

Bashir M, Wolfson T, Gamst A et al. (2019) Hepatic R2* is more strongly associated with proton density fat fraction than histologic liver iron scores in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 49 (5): 1456–1466.

Mamidipalli A, Hamilton G, Manning P et al. (2018) Cross-sectional correlation between hepatic R2* and proton density fat fraction (PDFF) in children with hepatic steatosis. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 47 (2): 418–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25748

Bydder M, Hamilton G, de Rochefort L et al. (2018) Sources of systematic error in proton density fat fraction (PDFF) quantification in the liver evaluated from magnitude images with different numbers of echoes. NMR in Biomedicine 31 (1): https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.3843

Bydder M, de Rochefort L, Hamilton G et al. (2018) The change in R2* with PDFF in liver can be explained by the water/fat susceptibility difference. Jt. Annu. Meet. ISMRM-ESMRMB, Paris, 16–21 June 2018

Hutton C, Gyngell M, Milanesi M et al. (2018) Validation of a standardized MRI method for liver fat and T2* quantification. PLOS ONE 13 (9): e0204175.

Reeder S, Pineda A, Wen Z et al. (2005) Iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL): application with fast spin-echo imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 54 (3): 636–644.

Reeder S, McKenzie C, Pineda A et al. (2007) Water-fat separation with IDEAL gradient-echo imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 25 (3): 644–652.

Reeder SB, Sirlin CB (2010) Quantification of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America 18 (3): 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mric.2010.08.013

Yokoo T, Pirasteh A, Bashir M et al. (2016) Proton-Density Fat Fraction Biomarker Committee: a meta-analysis interim report 2016. Radiol. Soc. North Am. 102nd Sci. Assem. Annu. Meet. Chicago, 27 November–2 December 2016

Yokoo T, Serai S, Pirasteh A et al. (2018) Linearity, bias, and precision of hepatic proton density fat fraction measurements by using MR imaging: a meta-analysis. Radiology 286 (2): 486–498.

Hernando D, Sharma SD, Aliyari M et al. (2017) Multi-site, multi-vendor validation of the accuracy and reproducibility of proton-density fat-fraction quantification at 1.5T and 3T using a fat-water phantom. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 77 (4): 1516–1524. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26228

Thomas EL, Hamilton G, Patel N et al. (2005) Hepatic triglyceride content and its relation to body adiposity: a magnetic resonance imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Gut 54 (1): 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.036566

Liu C, McKenzie C, Yu H et al. (2007) Fat quantification with IDEAL gradient echo imaging: correction of bias from T(1) and noise. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 58 (2): 354–364.

Leporq B, Ratiney H, Pilleul F, Beuf O (2013) Liver fat volume fraction quantification with fat and water T1 and T2* estimation and accounting for NMR multiple components in patients with chronic liver disease at 1.5 and 3.0 T. Eur Radiol 23 (8): 2175–2186.

Le T-A, Chen J, Changchien C et al. (2012) Effect of colesevelam on liver fat quantified by magnetic resonance in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 56 (3): 922–932. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25731

Dixon W (1984) Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology 153 (1): 189–194.

Glover G, Schneider E (1991) Three-point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 18 (2): 371–383.

Reeder S, Wen Z, Yu H et al. (2004) Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 51 (1): 35–45.

Hernando D, Liang Z-P, Kellman P (2010) Chemical shift-based water/fat separation: a comparison of signal models. Magn Reson Med 64 (3): 811–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22455

Yu H, Shimakawa A, Hines CDG et al. (2011) Combination of complex-based and magnitude-based multiecho water-fat separation for accurate quantification of fat-fraction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 66 (1): 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22840

Heba ER, Desai A, Zand KA et al. (2016) Accuracy and the effect of possible subject-based confounders of magnitude-based MRI for estimating hepatic proton density fat fraction in adults, using MR spectroscopy as reference. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 43 (2): 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25006

Dennis A, Kelly M, Fernandes C et al. (2020) Correlations between MRI biomarkers PDFF and cT1 with histopathological features of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Frontiers in Endocrinology. submitted

Wagner M, Corcuera-Solano I, Lo G et al. (2017) Technical failure of MR elastography examinations of the liver: experience from a large single-center ttudy. Radiology 284 (2): 401–412.

Loomba R, Cui J, Wolfson T et al. (2016) Novel 3D magnetic resonance elastography for the noninvasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD: A prospective study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 111 (7): 986–994. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.65

Morisaka H, Motosugi U, Glaser KJ et al. (2017) Comparison of diagnostic accuracies of two- and three-dimensional MR elastography of the liver. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 45 (4): 1163–1170.https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25425

Trout AT, Serai S, Mahley AD et al. (2016) Liver stiffness measurements with MR elastography: agreement and repeatability across imaging systems, field strengths, and pulse sequences. Radiology 281 (3): 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016160209

Yasar TK, Wagner M, Bane O et al. (2016) Inter-platform reproducibility of liver and spleen stiffness measured with MR elastography. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 43 (5): 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25077

Singh S, Venkatesh SK, Loomba R et al. (2016) Magnetic resonance elastography for staging liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a diagnostic accuracy systematic review and individual participant data pooled analysis. European Radiology 26 (5): 1431–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3949-z

Serai SD, Obuchowski NA, Venkatesh SK et al. (2017) Repeatability of MR elastography of liver: a meta-analysis. Radiology 285 (1): 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017161398

Dzyubak B, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Ehman RL (2017) Automated Liver Elasticity Calculation for 3D MRE. Proceedings of SPIE--the International Society for Optical Engineering 10134 101340Y. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2254476.

Harrison S, Roberts K, Paredes AH et al. (2017) Prospective prevalence study of adult NAFLD/NASH utilising multi-modality imaging compared with liver biopsy. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Brussels, 19–23 April

Huwart L, Sempoux C, Vicaut E et al. (2008) Magnetic resonance elastography for the noninvasive staging of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 135 (1): 32–40.

Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C et al. (2017) Magnetic resonance elastography vs transient elastography in detection of fibrosis and noninvasive measurement of steatosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 152 (3): 598-607.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.026

Harrison S, Dennis A, Fiore M et al. (2018) Utility and variability of three non-invasive liver fibrosis imaging modalities to evaluate efficacy of GR-MD-02 in subjects with NASH and bridging fibrosis during a Phase 2 controlled study. PLOS ONE 13 (9): e0203054.

Ghoz HM, Kröner PT, Stancampiano FF et al. (2019) Hepatic iron overload identified by magnetic resonance imaging-based T2* is a predictor of non-diagnostic elastography. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 9 (6): 921–927. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims.2019.05.13

Cunha GM, Glaser KJ, Bergman A et al. (2018) Feasibility and agreement of stiffness measurements using gradient-echo and spin-echo MR elastography sequences in unselected patients undergoing liver MRI. The British Journal of Radiology 91 (1087): 20180126. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20180126

Raizner A, Shillingford N, Mitchell PD et al. (2017) Hepatic inflammation may influence liver stiffness measurements by transient elastography in children and young adults. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 64 (4): 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001376

Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM, Dall’Armellina E et al. (2010) Shortened modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (ShMOLLI) for clinical myocardial T1-mapping at 1.5 and 3 T within a 9 heartbeat breathhold. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 12 (1): 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-12-69

Dall’Armellina E, Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM et al. (2012) Cardiovascular magnetic resonance by non contrast T1-mapping allows assessment of severity of injury in acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 14 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-14-15

Puntmann VO, Voigt T, Chen Z et al. (2013) Native T1 mapping in differentiation of normal myocardium from diffuse disease in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 6 (4): 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.08.019

Everett RJ, Treibel TA, Fukui M et al. (2020) Extracellular Myocardial Volume in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 75 (3): 304 LP – 316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.032

Hoad C, Palaniyappan N, Kaye P et al. (2015) A study of T1 relaxation time as a measure of liver fibrosis and the influence of confounding histological factors. NMR Biomed 28 (6): 706–714.

Floyd RA, Yoshida T, Leigh JS (1975) Changes of tissue water proton relaxation rates during early phases of chemical carcinogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 72 (1): 56 LP – 58.

Bradley CR, Cox EF, Scott RA et al. (2018) Multi organ assessment of compensated cirrhosis patients using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Hepatology 69 (5): 1015–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.037

Chow K, Flewitt J, Pagano JJ et al. (2012) T(2)-dependent errors in MOLLI T(1) values: simulations, phantoms, and in-vivo studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 14 (Suppl 1): P281–P281. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-14-S1-P281

Tunnicliffe EM, Rajarshi B, Pavlides M et al. (2016) A model for hepatic fibrosis: the competing effects of cell loss and iron on shortened modified Look‐Locker inversion recovery T1 (shMOLLI‐T1) in the liver. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 45 (2): 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25392

101. Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM et al. (1999) Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. American Journal of Gastroenterology 94 2467.

Eddowes P, McDonald N, Davies N et al. (2018) Utility and cost evaluation of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 47 (5): 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14469

Mozes FE, Tunnicliffe EM, Pavlides M, Robson MD (2016) Influence of fat on liver T (1) measurements using modified Look–Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) methods at 3T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 44 (1): 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25146

Mozes FE, Tunnicliffe EM, Moolla A et al. (2019) Mapping tissue water T(1) in the liver using the MOLLI T(1) method in the presence of fat, iron and B(0) inhomogeneity. NMR in Biomedicine 32 (2): e4030–e4030. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.4030

Dong J, Liu Y, Ye H et al. (2019) Nuclear magnetic resonance evaluation of inflammatory activity from chronic viral Hepatitis B. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 35 (6): 1565–1569. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.35.6.1364

Ding L, Xiao L, Lin X et al. (2018) Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in patients with liver dysfunction of chronic viral hepatitis: segmental heterogeneity and relationship with Child-Turcotte-Pugh Class at 3 Tesla. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2018 2983725. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2983725

Chen F, Chen Y-L, Chen T-W et al. (2020) Liver lobe based intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion weighted imaging in hepatitis B related cirrhosis: Association with child-pugh class and esophageal and gastric fundic varices. Medicine 99 (2): e18671–e18671. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000018671

Petersen RJ, Nielsen NS, Johannesen HH et al. (2019) PET/DW-MRI for evaluating treatment in chronic hepatitis C patients. American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 9 (1): 84–92.

Zheng Y, Xu Y-S, Liu Z et al. (2019) Whole-Liver Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Histogram Analysis for the Diagnosis and Staging of Liver Fibrosis. Journal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26987

Taouli B, Chouli M, Martin A et al. (2008) Chronic hepatitis: role of diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis and inflammation. Journal Magnetic Resonance Imaging 28 (1): 89–95.

Liu Y, Dong JH, An WM et al. (2017) Quantitative Comparison of Diffusion Weighted Image in Liver at Two Field Strengths for Chronic Hepatitis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 97 (21): 1638–1642.

Kocakoc E, Bakan AA, Poyrazoglu OK et al. (2015) Assessment of Liver Fibrosis with Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using Different b-values in Chronic Viral Hepatitis. Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre 24 (6): 522–526https://doi.org/10.1159/000434682

Xiong, H., & Zeng YL (2016) Standard-b-value versus low-b-Value diffusion-weighted Imaging in hepatic lesion discrimination: a meta-analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 40 (3): 498–504.

Tavakoli A, Attenberger UI, Budjan J et al. (2019) Improved liver diffusion-weighted imaging at 3 T using respiratory triggering in combination with simultaneous multislice acceleration. Investigative Radiology 54 (12): 744–751.

Ichikawa S, Motosugi U, Morisaka H et al. (2014) MRI‐based staging of hepatic fibrosis: comparison of intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion‐weighted imaging with magnetic resonance elastography. Journal Magnetic Resonance Imaging 42 (1): 204–210.

Tosun M, Onal T, Uslu H et al. (2020) Intravoxel incoherent motion imaging for diagnosing and staging the liver fibrosis and inflammation. Abdom Radiol (NY) 45 (1): 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02300-z

Sandrasegaran K, Territo P, Elkady RM et al. (2018) Does intravoxel incoherent motion reliably stage hepatic fibrosis, steatosis, and inflammation? Abdominal Radiology 43 (3): 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-017-1263-8

Manning P, Murphy P, Wang K et al. (2017) Liver histology and diffusion-weighted MRI in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A MAGNET study. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 46 (4): 1149–1158. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25663

Porto G, Brissot P, Swinkels DW et al. (2016) EMQN best practice guidelines for the molecular genetic diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis (HH). European Journal of Human Genetics: EJHG 24 (4): 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.128

McKay A, Wilman HR, Dennis A et al. (2018) Measurement of liver iron by magnetic resonance imaging in the UK Biobank population. PLOS ONE 13 (12): e0209340–e0209340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209340

Wilman HR, Parisinos CA, Atabaki-Pasdar N et al. (2019) Genetic studies of abdominal MRI data identify genes regulating hepcidin as major determinants of liver iron concentration. Journal of Hepatology 71 (3): 594–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.05.032

Haemochromatosis UK The 2017 Genetic Haemochromatosis Patient Survey and Resulting Report. https://haemochromatosis.org.uk/2017-survey/

Pilling LC, Tamosauskaite J, Jones G et al. (2019) Common conditions associated with hereditary haemochromatosis genetic variants: cohort study in UK Biobank. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 364 k5222–k5222. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5222

Chitturi S, Weltman M, Farrell G et al. (2002) HFE mutations, hepatic iron, and fibrosis: ethnic-specific association of NASH with C282Y but not with fibrotic severity. Hepatology 36 142–149.

Hernaez R, Yeung E, Clark JM et al. (2011) Hemochromatosis gene and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hepatology 55 (5): 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.013

Nelson JE, Wilson L, Brunt EM et al. (2011) Relationship between pattern of hepatic iron deposition and histologic severity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 53 (2): 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24038

Wood JC (2015) Estimating tissue iron burden: current status and future prospects. British Journal of Haematology 170 (1): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13374

Terada T, Nakanuma Y (1989) Survey of iron-accumulative macroregenerative nodules in cirrhotic livers. Hepatology 10 (5): 851–854.

Loomba R, Yang H-I, Su J et al. (2013) Synergism between obesity and alcohol in increasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology 177 (4): 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws252doi: .

Sánchez-Jiménez BA, Brizuela-Alcántara D, Ramos-Ostos MH et al. (2018) Both alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis association with cardiovascular risk and liver fibrosis. Alcohol 69 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.11.004

Taylor R, Taylor R, Bayliss S et al. (2020) Association Between Fibrosis Stage and Outcomes of Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.043

Hong C, Wolfson T, Sy E et al. (2018) Optimization of region-of-interest sampling strategies for hepatic MRI proton density fat fraction quantification. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 47 (4): 988–994. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25843

Mojtahed A, Kelly C, Herlihy A et al. (2019) Reference range of liver corrected T1 values in a population at low risk for fatty liver disease-a UK Biobank sub-study, with an appendix of interesting cases. Abdomimal Radiology (NY) 44 (1): 72–84.

Thomaides-Brears, HB Shumbayawonda E, Mouchti S, Castelo-Branco M et al. (2019) Characterization of MR derived biomarkers of liver health in a European cohort with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD in comparison to healthy controls: Preliminary analysis of an ongoing prospective trial (RADIcAL1). AASLD, Liver Meet. Boston, 10–12 November.

Costa-Silva L, Ferolla SM, Lima AS et al. (2018) MR elastography is effective for the non-invasive evaluation of fibrosis and necroinflammatory activity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. European Journal of Radiology 98 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.11.003

Müller A, Hochrath K, Stroeder J et al. (2017) Effects of liver fibrosis progression on tissue relaxation times in different mouse models assessed by ultrahigh field magnetic resonance imaging. BioMed Research International 2017 (8720367): 10.

McKay A, Dennis A, Kelly M et al. (2019) Multi-parametric MRI as a composite biomarker for NASH and NASH with fibrosis. Keystone Integr. Pathways Dis. NASH NAFLD Symp. St. Fe, New Mex. 20–24 January

Loomba R, Wolfson T, Ang B et al. (2014) Magnetic resonance elastography predicts advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 60 (6): 1920–1928. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27362

Chen J, Talwalkar JA, Yin M et al. (2011) Early detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by using MR elastography. Radiology 259 (3): 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11101942

Harrison S, Roberts K, Lisanti C et al. (2019) Predicting the Severity of Hepatic Steatosis and fibrosis by Transient Elastography and MRI-based techniques in Adult Patients with Suspected NAFLD. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Vienna, 10–14 April

Aslam F, Mouchti S, Dennis A et al. (2019) Non-invasive imaging modalities for assesment of fibrosis, inflammation and steatosis in a Japanese NASH population. AASLD, Liver Meet. Boston, 10–12 November

Milić S, Lulić D, Štimac D (2014) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: Biochemical, metabolic and clinical presentations. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG 20 (28): 9330–9337https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9330

Friedman S, Neuschwander-Tetri B, Rinella M, Sanyal A (2018) Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nature Medicine 24 (7): 908–922.

Younossi ZM, Ratziu V, Loomba R et al. (2019) Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet 394 (10215): 2184–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33041-7

Romero FA, Jones CT, Xu Y et al. (2020) The Race to Bash NASH: Emerging targets and drug development in a complex liver disease. J Med Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01701

Harrison S (2018) MGL-3196, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonist significantly decreases hepatic fat in NASH patients at 12 weeks, the primary endpoint in a 36 week serial liver biopsy study. https://livertree.easl.eu/easl/2018/international.liver.congress/210658/stephen.harrison.mgl-3196.a.selective.thyroid.hormone.receptor-beta.agonist.html. Accessed June 2018.

Harrison S, Rossi S, Paredes AH et al. (2020) NGM282 Improves Liver Fibrosis and Histology in 12 Weeks in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 71 (4): 1198–1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30590

Lawitz EJ, Coste A, Poordad F et al. (2018) Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor GS-0976 for 12 weeks reduces hepatic de novo lipogenesis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clinical Gastroenterology & Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.042

Wilman HR, Kelly M, Garratt S et al. (2017) Characterisation of liver fat in the UK Biobank cohort. PLOS ONE 12 (2): e0172921. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172921

Levelt E, Pavlides M, Banerjee R et al. (2016) Ectopic and Visceral Fat Deposition in Lean and Obese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 68 (1): 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.597

Ostovaneh M, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Fuji T et al. (2018) Association of liver fibrosis with cardiovascular diseases in the general population: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 11 e007241.

Mangla N, Ajmera VH, Caussy C et al. (2020) Liver Stiffness Severity is Associated With Increased Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 18 (3): 744-746.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.003

Jayaswal A, Pavlides M, Banerjee R et al. (2018) cT1 is accurate as biopsy at predicting outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. AASLD, Liver Meet. San Fransisco, 9–13 November

Jayaswal A, Pavlides M, Banerjee R et al. (2019) Liver cT1 predicts clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Vienna, 10–14 April

Jayaswal AN., Barnes E, Banerjee R et al. (2020) Prognostic value of multiparametric MRI, transient elastography and serum fibrosis markers in patients with chronic liver disease. Liver International (in press)

Levick C, Phillips-Hughes J, Collier J et al. (2019) Non-invasive assessment of portal hypertension by multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging of the spleen: A proof of concept study. PLOS ONE 14 (8): e0221066–e0221066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221066

Dillman J, Serai S, Trout A et al. (2019) Diagnostic performance of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers for predicting portal hypertension in children and young adults with autoimmune liver disease. Pediatric Radiology 49 (3): 332–341.

Pik-Eu Chang J, Jayaswal AN., Tim-Ee Cheng L et al. (2020) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of liver and spleen is a reliable non-invasive predictor of clinically relevant hepatic venous pressure gradient thresholds and predicts failure of primary prophylaxis for variceal bleeding. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. submitted

Shin SU, Lee J-M, Yu MH et al. (2014) Prediction of esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: usefulness of three-dimensional MR elastography with echo-planar imaging technique. Radiology 272 (1): 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14130916

Yoon H, Shin HJ, Kim M-J et al. (2019) Predicting gastroesophageal varices through spleen magnetic resonance elastography in pediatric liver fibrosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology 25 (3): 367–377. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i3.367

Trout AT, Sheridan RM, Serai SD et al. (2018) Diagnostic performance of MR elastography for liver fibrosis in children and young adults with a spectrum of liver diseases. Radiology 287 (3): 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018172099

Thomaides-Brears H, Barragán E, de Celis Alonso B et al. (2019) Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a Mexican paediatric population diagnosed non-invasively by multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. ISMRM Work. MRI Obes. Metab. Disord. Singapore, 21–24 July 2019

Halliday D, Simpson H, Borghetto A et al. (2019) Repeatability and reproducibility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the liver in children. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Vienna, 10–14 April

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2017) Non-invasive assessment of paediatric liver disease with multiparametric MRI. AASLD, Liver Meet. Washington, 20–24 Oct.

Jayaswal A, Levick C, Collier J et al. (2020) Liver cT1 decreases following direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus – a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One submitted

Zawada E, Serafin Z, Dybowska D et al. (2019) Monoexponential and biexponential fitting of diffusional magnetic resonance imaging signal analysis for prediction of liver fibrosis severity. J Comput Assist Tomogr 43 (6): 857–862.

Lee C, Peng S, Lee C et al. (2019) Transient elastography correlated with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and cholestatic complications. J Formos Med Assoc 118 (11): 1522–1527.

Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN et al. (2019) Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis in adults and children: 2019 practice guidance and guidelines from the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology doi:10.1002/hep.31065. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31065

Hoeroldt B, McFarlane E, Dube A et al. (2011) Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Autoimmune Hepatitis Managed at a Nontransplant Center. Gastroenterology 140 (7): 1980–1989. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.065

Gleeson D, Heneghan MA (2011) British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut 60 (12): 1611–1629. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.235259

Dhaliwal H, Hoeroldt B, Dube A et al. (2015) Long-term prognostic significance of persisting histological activity despite biochemical remission in autoimmune hepatitis. American Journal Gastroenterol 110 (7): 993–999.

Tsiotsios C, Stewart R, Milanesi M et al. (2016) Multiparametric MRI could help track AIH patient response to therapy as alternate to biopsy. Panhellenic Congr. Radiol. Athens, 4–6 November

Arndtz K, Hodson J, Eddowes P et al. (2017) Multi-parametric MRI imaging correlates with clinically meaningful surrogates of disease activity in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 66 188A.

Arndtz K, Shumbayawonda E, Hodson J et al. (2020) Multiparametric MRI imaging, autoimmune hepatitis, and prediction of disease activity. Hepatology. submitted

Arndtz K, Hodson J, Eddowes P et al. (2018) Cross-sectional, prospective, evaluation of the utility of multi-parametric MRI imaging in predicting clinically meaningful outcomes in autoimmune hepatitis. AASLD, Liver Meet. San Fr. 9–13 November

Wang J, Malik N, Yin M et al. (2017) Magnetic resonance elastography is accurate in detecting advanced fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology 23 (5): 859–868. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i5.859.

Arndtz K, Hodson J, Eddowes P et al. (2018) Evaluation of multiparametric MRI in comparison with MR elastography in patients evaluated for chronic liver disease. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Paris, 11–15 April

Hindman NM, Arif-Tiwari H, Kamel IR et al. (2019) ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Jaundice. Journal of the American College of Radiology 16 (5): S126–S140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2019.02.012

Goldfinger MH, Ridgway GR, Ferreira C et al. (2020) Quantitative MRCP Imaging: Accuracy, Repeatability, Reproducibility, and Cohort-Derived Normative Ranges. Journal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.27113

Gilligan LA, Trout AT, Lam S et al. (2020) Differentiating pediatric autoimmune liver diseases by quantitative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Abdominal Radiology 45 (1): 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02184-z

Gomez-Castaneda, E., Janowski, K., Dennis, A., Kazimianec, A., Shumbayawonda, E., Pronicki, M., Grajkowska, W., Wozniak, M., Pawliszak, P., Jurkiewicz, E., Kelly, M., Neubauer, M., Banerjee, R., Socha P (2019) Multi-parametric liver MRI can discriminate between treatment naïve autoimmune hepatitis patients and those under treatment in the paediatric Kids 4 Life cohort. AASLD, Liver Meet. Boston, 10–12 November

Janowski K, Shumbayawonda E, Dennis A et al. (2020) Multiparametric MRI as a non-invasive monitoring tool for children with autoimmune liver disease. Journal Paediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. submitted

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2019) A combined blood and MR imaging risk score for monitoring liver inflammation in paediatric auto-immune hepatitis. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Vienna, 10–14 April

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2018) MRI as a biomarker for Wilson’s disease in children: early observations from a larger trial into paediatric liver disease. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Paris, 11–15 April

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2018) MRI as a biomarker for Wilson’s Disease in children: early observations from a larger trial into paediatric liver disease. EASL Int. Liver Congr. Paris, 11–15 April 2018 ESPGHAN, Prague, 10–13 May

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2019) Multi-parametric MRI as a composite biomarker for classifying liver disease in paediatrics. ECR, Vienna, 27 Feb-3 March

Janowski K, Dennis A, Kin S et al. (2017) Multi-parametric MRI as a biomarker for paediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis: Preliminary observations. CALD Pediatr. Autoimmune Liver Dis. Symp. Cincinatti, 8–9 Oct.

Wood JC, Pressel S, Rogers ZR et al. (2015) Liver iron concentration measurements by MRI in chronically transfused children with sickle cell anemia: baseline results from the TWiTCH trial. American Journal of Hematology 90 (9): 806–810. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24089

Yasar TK, Wagner M, Bane O et al. (2016) Interplatform reproducibility of liver and spleen stiffness measured with MR elastography. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 43 (5): 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25077

Garbowski MW, Carpenter J-P, Smith G et al. (2014) Biopsy-based calibration of T2* magnetic resonance for estimation of liver iron concentration and comparison with R2 Ferriscan. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 16 (1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-16-40

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

HTB, CD and RB are employees of and RB is shareholder of Perspectum Ltd, a company with intellectual property on analysis of data acquired by MOLLI T1, T2* and PDFF included in the review. RL has no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomaides-Brears, H.B., Lepe, R., Banerjee, R. et al. Multiparametric MR mapping in clinical decision-making for diffuse liver disease. Abdom Radiol 45, 3507–3522 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-020-02684-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-020-02684-3