Abstract

Purpose

The serotonin system is undoubtedly involved in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder (MDD). More specifically the serotonin transporter (SERT) serves as a major target for antidepressant drugs. There are conflicting results about SERT availability in depressed patients versus healthy controls. We aimed to measure SERT availability and study the effects of age, gender and season of scanning in MDD patients in comparison to healthy controls.

Methods

We included 49 depressed outpatients (mean±SD 42.3 ± 8.3 years) with a Hamilton depression rating scale score above 18, who were drug-naive or drug-free for ≥4 weeks, and 49 healthy controls matched for age (±2 years) and sex. Subjects were scanned with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using [123I]β-CIT. SERT availability was expressed as specific to nonspecific binding ratios (BPND) in the midbrain and diencephalon with cerebellar binding as a reference.

Results

In crude comparisons between patients and controls, we found no significant differences in midbrain or diencephalon SERT availability. In subgroup analyses, depressed males had numerically lower midbrain SERT availability than controls, whereas among women SERT availability was not different (significant diagnosis×gender interaction; p = 0.048). In the diencephalon we found a comparable diagnosis×gender interaction (p = 0.002) and an additional smoking×gender (p = 0.036) interaction. In the midbrain the season of scanning showed a significant main effect (p = 0.018) with higher SERT availability in winter.

Conclusion

Differences in SERT availability in the midbrain and diencephalon in MDD patients compared with healthy subjects are affected by gender. The season of scanning is a covariate in the midbrain. The diagnosis×gender and gender×smoking interactions in SERT availability should be considered in future studies of the pathogenesis of MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent and disabling disease, often treated by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [1]. SSRIs block the serotonin transporter (SERT), which lowers the reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) from the synaptic cleft and increases neurotransmission. Despite the fact that the working mechanism of antidepressants supports the monoamine deficiency theory, the pathogenesis of MDD remains unclear [2, 3]. Therefore, differences in SERT availability between patients and healthy subjects have been studied previously.

Post-mortem studies have shown reduced or unchanged concentrations of SERTs in MDD patients compared with healthy subjects, but these studies may have been biased by retrospective data collection, previous antidepressant use, suicidal behaviour apart from MDD or nonselective ligands (reviewed by Stockmeier [4]).

Cerebral SERTs in humans can be quantified in vivo with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The first SERT radioligand, 123I-labelled 2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-tropane ([123I]β-CIT) binds to both SERTs and dopamine transporters (DATs) [5]. [123I]β-CIT binding in the diencephalon and midbrain predominantly reflect SERTs, while striatal [123I]β-CIT uptake reflects DATs [6].

Studies comparing depressed patients with healthy subjects have shown decreased [7–13], unchanged [14–18] or increased [19] SERT availability in MDD patients. A negative correlation between SERT availability and the severity of depression, measured in terms of Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) scores, has been reported in patients with primary MDD [9] or Wilson’s disease [20]. Discrepant results among studies may be explained by differences in scanning techniques, analytical methods, and subject sampling, although the effects of additional variables and their interaction might also explain conflicting results. Staley et al. reported lower SERT availability in the diencephalon of female MDD patients than in healthy subjects [11], and suggested that this interaction accounted for the contradictory results between studies. Furthermore, in healthy subjects significant effects on SERT availability have been reported for gender [21], smoking behaviour [21], ageing [22, 23] and season of scanning [24, 25].

Our objectives were to quantify SERT availability in MDD patients in comparison to healthy subjects while accounting for these potential covariates and possible interactions, and to correlate SERT availability with the severity of depression. Therefore, we compared [123I]β-CIT SPECT scans of drug-free MDD patients with age- and sex-matched healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Subjects

After receiving approval of the institutional ethics committee and written informed consent, we recruited depressed patients from primary care, and our outpatient department (October 2003 to August 2006). Patients were eligible if they were 25–55 years old, had a diagnosis of MDD (diagnosed by structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, SCID patient version), had a HDRS score of >18, were antidepressant-free, and were using no more than one antidepressant (stopped for >4 weeks and ≥5 half-lives of this antidepressant before scanning) for the present MDD episode. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy (or desire to become pregnant), bipolar disorder, psychotic features, primary anxiety and/or substance abuse disorders, and acute, severe suicidal ideation. Secondary comorbid anxiety and/or substance abuse were allowed.

We individually matched each patient by gender and age (±2 years). Healthy controls were in good physical health and had never used psychotropic medication. Exclusion criteria were current or life-time psychiatric disorder(s) according to the SCID (including abuse or addiction disorders), a Beck depression inventory (BDI) score of >9, alcohol use >4 units per day (last month) or a first-degree relative with psychiatric disorder(s). We allowed the controls to have incidentally used illicit drugs unless criteria for a DSM-IV disorder were met, but prohibited illicit drug use the month prior to scanning. Illicit drug use was not tested at the time of scanning. Patients and controls received €50 and €40, respectively. No restrictions were made with respect to smoking behaviour.

Procedure and SPECT imaging

We performed all scans 230 ± 18 min (mean±SD) after intravenous injection of approximately 100 MBq [123I]β-CIT, when the radioligand was at equilibrium for SERT binding in brain areas expressing high densities of SERTs [22]. Radiosynthesis of [123I]β-CIT and image acquisition were as described previously [26]. We performed SPECT imaging using a 12-detector single slice brain-dedicated scanner (Neurofocus 810; Strichmann Medical Equipment, Cleveland, OH) with a full-width at half-maximum resolution of 6.5 mm, throughout the 20-cm field-of-view. The Neurofocus system is an upgrade of the SME 810 system [27], and acquires sequential single transaxial brain sections. Up to 24 axial sections 5 mm apart were scanned, and the energy window (140–178 keV) was placed symmetrically around the 123I gamma energy of 159 keV. This system uses 800-hole long-bore, point-focused, collimators to obtain high-resolution images.

Image analysis

After attenuation correction (based on an automatically detected ellipse matching the outer head surface), and reconstruction in 3-D mode (based on a maximum a-posteriori reconstruction), we selected regions of interest (ROIs) for the midbrain, diencephalon and cerebellum by using validated templates (Fig. 1) [26]. One examiner (H.G.R.), blinded to the diagnosis, positioned all ROIs in two series. Intraclass correlation coefficients were ≥0.98 for all ROIs. If the two series differed by >5%, scans were reevaluated by a second investigator (J.B.). In the analyses the counts for the two series were averaged.

Examples of SPECT images after 3-D reconstruction showing the ROIs for the midbrain, cerebellum and diencephalon. Templates with fixed ROIs are shown in green. a Midbrain (circle) and cerebellum. b Striatum (for midbrain–diencephalon demarcation) and diencephalon (circle). ROIs were positioned by hand based on anatomy and maximum concentration of activity per millilitre in the ROI

We assumed that activity in the cerebellum represented nondisplaceable activity (nonspecific binding and free radioactivity) [28]. We calculated the binding potential (BP) as the rate of specific to nondisplaceable (ND) binding (Z) for midbrain and diencephalon [29]. BPND is proportional to transporter number under equilibrium conditions.

Statistics

General linear models were used to analyse differences in BPND in the midbrain and diencephalon between depressed patients and controls using the following modelling strategy.

We first compared mean BPND between MDD patients and controls in univariable (‘crude’) models, only containing the main effect of diagnosis (categorical: MDD/control). We then fitted multivariable models by adding variables to the model, which in the literature have been reported to influence BPND. These variables included: gender (categorical: male/female), age (continuous), smoking (categorical: yes/no), season of scanning (categorical: “winter”/“summer”; winter October–March, summer April–September [24, 25]). In addition, a number of specific two-way interactions were examined, again because they have previously been reported to be significant, which included: diagnosis×gender, diagnosis×smoking, gender×smoking (‘full multivariable models’) [11, 21]. Three-way interactions were not examined because of the relatively small sample size (from a statistical perspective). The Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to judge whether the two-way interactions improved the model. If a two-way interaction did not improve the fit of the model, it was removed from the model in order to facilitate the interpretation of the model (‘reduced multivariable models’). Main effects always remained in the model, irrespective of their significance, in order to report their (lack of) impact. Diencephalon and midbrain data were analysed separately, but the same set of variables and interaction terms were examined using the same modelling approach. If significant interactions were present, post-hoc analyses were performed in order to report the absolute differences in SERT availability in the involved subgroups. Differences between subgroups were analysed within the framework of the multivariable model and tested for significance using the residual variance estimate of the model.

We examined the association of BPND with HDRS scores using linear regression models in patients, correcting for covariates used in the multivariable models. We used SPSS (version 15.0.1) for statistical procedures (http://www.spss.com). All results are expressed as means±SD, except in Fig. 2, where ±SEM was used for legibility.

Results

We studied 17 male and 32 female patients with MDD, versus 17 male and 32 female healthy controls (Table 1). Significantly more patients than controls smoked (27 patients, 55.1%; 11 controls, 22.4%; χ2=11.2; df 2; p = 0.004). There were significantly more Caucasians among the controls (n = 44; 89.8%) than among the patients (n = 31; 63.3%; χ2=11.9; df 3; p = 0.008). We scanned 67% of patients and 55% of controls in winter (χ2=1.55, df 1, p = 0.213). In one female patient insufficient cerebellum was scanned as a reference, and in three patients and one control midbrain slices were insufficient; these were omitted from the analyses. Of 15 patients who had used antidepressants during their life, 3 had been using antidepressants for the current episode. One patient had used mirtazapine until 4 weeks before scanning; all others had stopped antidepressants 6–132 months before scanning. Illicit drug abuse mainly involved cannabis. Life-time MDMA use occurred in none of the patients and in one female control (fewer than ten tablets; last use 8 months before scanning).

SERT availability in MDD patients versus healthy controls (‘crude models’)

Midbrain BPND in patients (0.62 ± 0.22) was not significantly different from that in controls (0.63 ± 0.19; F 1,94=0.118; p = 0.733). Diencephalon BPND was 1.15 ± 0.24 in patients and 1.09 ± 0.26 in controls (F 1,97=1.209; p = 0.274).

Multivariable models of SERT availability in MDD patients versus healthy controls

Midbrain

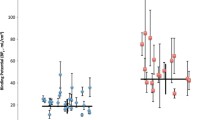

For the midbrain, the full multivariable model (including diagnosis, gender, age, smoking, season of scanning, diagnosis×gender, diagnosis×smoking, and gender×smoking) was subsequently reduced by removing the nonsignificant interaction terms diagnosis×smoking and gender×smoking (AIC decrease 2.478; Fig. 2a). This reduced multivariable model showed a significant diagnosis×gender interaction (F 1,87=4.039; p = 0.048). In post-hoc comparisons, MDD males showed a trend for lower BPND compared with male controls (difference −0.124; t 87=−1.718; p = 0.089), while female patients and controls did not differ significantly (difference 0.047; t 87=0.898; p = 0.372). Furthermore, the main effect of season of scanning was significant (F 1,87=5.814; p = 0.018). Scans performed in winter showed on average 18% higher BPND than scans performed in summer (F 2,87=3.248; p = 0.044). The main effects of age and smoking were also included in this reduced model, but were not significant (p = 0.227 and p = 0.582, respectively; Fig. 2a).

BPND values for the midbrain and diencephalon. Multivariable models for BPND in MDD patients (MDD) versus healthy controls (HC) stratified for gender. Values are estimated means ±SEM. a Midbrain (n = 94), corrected for main effects of diagnosis (p = 0.414), gender (p = 0.128), season of scanning (F 1,87=5.814; p = 0.018), smoking (p = 0.582), age (p = 0.227) and diagnosis×gender interaction (F 1,87=4.039; p = 0.048). *Post-hoc differences t 87=−1.718; p = 0.089 between: MDD males and control males. b Diencephalon (n = 97), corrected for main effects of diagnosis (p = 0.476), gender (p = 0.277), season of scanning (p = 0.679), smoking (p = 0.223), age (p = 0.247) and diagnosis×gender interaction (F 1,88=10.227; p = 0.002), gender×smoking interaction (F 1,88=4.541; p = 0.036) and diagnosis×smoking interaction (p = 0.127). *Post-hoc difference t 88=−2.384; p = 0.019 between smoking male controls and nonsmoking male controls. **Post-hoc differences t88>2.643; p < 0.01 between: smoking male MDD patients and smoking male controls, nonsmoking female MDD patients and nonsmoking female controls

Diencephalon

For the diencephalon, the full multivariable model (including the same variables as for the midbrain) could not be reduced, as all three interaction terms (diagnosis×smoking, diagnosis×gender and smoking×gender) improved the fit of the model as evaluated by the AIC (Fig. 2b). This full multivariable model showed significant diagnosis×gender (F 1,88=10.227; p = 0.002) and smoking×gender (F 1,88=4.541; p = 0.036) interactions. The diagnosis×smoking interaction was not significant (p = 0.127). In post-hoc comparisons, smoking male MDD patients had significantly lower BPND than smoking male controls (difference −0.304; t 88=−2.643; p = 0.010). In nonsmoking male MDD patients, BPND was numerically lower than in nonsmoking male controls (difference −0.140; t 88=−1.340; p = 0.184). In contrast, nonsmoking female patients had higher BPND than nonsmoking female controls (difference 0.221; t 88=3.064; p = 0.003) with almost no difference in BPND between smoking female MDD patients and controls (difference 0.057; t 88=0.616; p = 0.539). Furthermore, smoking male controls had significantly higher BPND than nonsmoking male controls (difference 0.279; t 88=−2.384; p = 0.019), while in female controls, BPND was not affected by smoking (difference 0.032; t 88=−0.371; p = 0.712). The main effects of season of scanning and age were also included in this model, but were not significant (p = 0.679 and p = 0.247, respectively; Fig. 2b).

Relationship between SERT availability and severity of MDD

Linear regression models showed no significant relationship between HDRS scores and BPND, either in the midbrain or in the diencephalon when taking into account gender, age, smoking and season of scanning.

Discussion

In the present – until now largest – study of MDD patients in comparison to healthy subjects, we aimed to quantify SERT availability in MDD patients and healthy subjects while taking into account covariates and interactions, and to determine the degree correlation between SERT availability and depression severity. We did not find significant differences in SERT availability in the midbrain or diencephalon in crude comparisons. However, a significant diagnosis×gender interaction was found in the midbrain and diencephalon, combined with a significant gender×smoking interaction in the diencephalon only. Depressed males, but not females, had lower midbrain SERT availability than healthy controls. In the diencephalon smoking male MDD patients had significantly lower SERT availability than smoking male controls, while nonsmoking female patients had higher SERT availability than nonsmoking female controls. Furthermore, the season of scanning influenced SERT availability in the midbrain, with higher SERT availability in winter. We found no clinically relevant correlation between HDRS scores and SERT availability.

Comparison with previous studies

Our results confirm previous reports of similar SERT availability in the midbrain and diencephalon in MDD patients and healthy subjects [14–18]. Other studies have shown increased [19] or decreased [7–13] SERT availability in MDD patients compared with healthy subjects. However, none of these studies except two [11, 13] investigated the effect of gender, and none of the study corrected for season. Furthermore, we confirmed a significant contribution of season of scanning on midbrain BPND [24].

The diagnosis×gender interaction in the midbrain and diencephalon is our most important finding. In contrast to the findings of Staley et al. [11, 21], we found a different direction of this interaction in the diencephalon: significantly lower BPND in male MDD patients in the midbrain (−17%) and diencephalon (−18%), and higher BPND in female MDD patients in the midbrain (+9%, nonsignificant) and diencephalon (+13%, significant) than in healthy subjects. Staley et al. found 1% lower SERT availability in the diencephalon in male MDD patients, and 22% lower SERT availability in the diencephalon in female MDD patients. We found a gender×smoking interaction in the diencephalon (with highest BPND in smoking male healthy controls), while Staley et al. found higher SERT availability in the brainstem (attributable to males). Our findings suggest that a failure to stratify for a diagnosis×gender interaction may obscure differences between patients and healthy subjects.

Methodological explanations for inconsistent findings

Despite technical differences between studies (scanning protocols, radioligands, image analyses), variation in the selection of healthy controls (e.g. having relatives with psychiatric diagnoses) or patients (from different source populations) is the most probable explanation for the inconsistent findings. Previous studies recruited patients from general psychiatric outpatient and university clinics [7, 8, 10, 12, 18, 19, 30]. We recruited 65% of our patients from primary care settings. We adequately diagnosed patients by SCID, and required an HDRS score of >18 for inclusion. Thus, we recruited severely affected and often melancholic patients who were drug-free, with 69% of the patients being drug-naive. Three studies [7, 13, 31] included larger proportions of drug-naive patients. Like Parsey et al. [10], we observed (nonsignificant −15%) lower midbrain SERT availability in drug-naive patients (results available on request). Additionally, some studies have suggested that anxiety disorders influence SERT availability [32], and MDD with comorbid anxiety may differ from ‘pure MDD’. However, this was not observed in our sample (results available on request).

Role of SERT in the pathogenesis of MDD

SERTs evacuate extracellular 5-HT from the synapse. Observed differences in SERTs between patients and healthy subjects may represent differences in the number of SERT-containing neurons, in the number of SERTs per neuron or a combination of both.

Two major mechanisms for the role of SERT in MDD have been hypothesized [32]. First, increased SERT availability reduces 5-HT from the synapse more easily, which might lower 5-HT transmission, possibly leading to MDD. Second, as the brain might apply compensation mechanisms to retain homeostasis, a decreased 5-HT transmission as a result of MDD may result in downregulation (decrease) of SERT in order to increase 5-HT transmission. A sequential occurrence of these two mechanisms could also be hypothesized: an initially increased SERT availability destabilizes (with or without an additional factor) and leads to MDD, which is followed by a decrease in SERT to compensate for decreased 5-HT transmission.

Differential effects of MDD on SERT availability between sexes may be explained via sex hormones. Oestrogen replacement after ovariectomy has been shown to increase SERT mRNA and SERT availability in female rats [33] and in hypothalamic regions of female macaques [34]. Depressed women may have significantly higher 24-h mean levels of diurnal oestradiol rhythms, and may have higher testosterone levels than healthy individuals [35]. Testosterone may increase SERT availability by conversion to oestrogen by aromatase, which is especially available in the diencephalon. This could explain our finding of increased SERT availability in the diencephalon in females. In depressed men, the sex steroid testosterone is decreased [35], with 34–61% biochemical hypogonadism in depressed males compared with 6–14% in healthy individuals [36]. This lack of testosterone in MDD may reduce SERT availability as a result of reduced conversion to oestrogen. Replacement of testosterone in castrated male rats increases SERT mRNA and SERT availability [37]. Since we did not measure sex hormones, and Best et al. [38] found no relationship between menstrual cycle or sex hormones and SERT availability in healthy individuals, these explanations remain speculative and should be examined further.

We confirmed a main effect of season demonstrated previously in the diencephalon in 12 healthy women [39] and the mesencephalon in 29 healthy individuals [24] and various brain regions in 88 healthy individuals [25]. Neumeister et al. observed decreased SERT availability in winter [39]. In contrast, Buchert et al. [24] and Praschak-Rieder et al. [25] found increased SERT availability in winter, which was also found in our study. Serotonin modulates the effects of photic input in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN imposes a circadian rhythm by affecting hormonal and autonomic output (reviewed by Buijs et al. [40]). Serotonin release in the SCN is highest during waking and activity [41]. Because raphe neurons show regular high firing rates during waking and decreased firing during sleep, it could be hypothesized that during winter, with decreased daylight, more serotonergic activity is needed, which may be mediated via the raphe input into the SCN [42]. Increased serotonergic activity (increased free synaptic serotonin) may result in a compensatory increase in SERTs. Nevertheless, the small size of the SCN (about 0.27 mm3) by itself cannot explain higher SERT availability found by SPECT or PET.

Limitations of the present study

The cerebellum (especially the vermis) contains small amounts of SERT [43, 44], which could result in an underestimation of BPND in patients and healthy controls, expected to be 7% at most [45]. [123I]β-CIT binds in vivo to SERT, DAT and norepinephrine transporters. Consequently, a systematic underestimation of SERT assessment due to increased DAT or norepinephrine transporters in the midbrain (substantia nigra and locus coeruleus, respectively) cannot be ruled out. Although recently Yang et al. measured a small but significant increased striatal DAT binding with [99mTc] TRODAT-1 SPECT in 10 MDD subjects versus 10 controls [46], we think the potential systematic underestimation of midbrain SERT is unlikely to explain the observed gender interactions between patients and healthy controls.

Second, lower levels of endogenous 5-HT (e.g. in MDD) could result in less competition with radioligands, increasing the specific binding measured. This has been demonstrated in rhesus monkeys with [123I]β-CIT SPECT [47] but not in humans. After tryptophan depletion (artificially reducing endogenous 5-HT) no differences in SERT availability were observed [48, 49] but the radioligand ([11C]DASB) in that study does not bind to the 5-HT recognition/translocation site, and may not be suitable for imaging such changes in extracellular 5-HT [50]. Third, we used previously validated ROIs [26] instead of magnetic resonance imaging for coregistration. Because these templates cover larger brain areas, BPND in small regions (raphe nuclei) cannot be determined. This potential measurement error (nondifferential for patients and controls), might have increased variance in our measurements, despite very good intrarater correlation coefficients. Additionally, we did not correct for nonuniform photon attenuation and partial volume effects in our gender analyses. Greater skull thickness might have led to an underestimation of BPND in males, and a smaller midbrain and diencephalon in females might have led to suppression of BPND compared with males. In future studies hybrid SPECT/CT may be useful to correct for nonuniform attenuation and better delineate the midbrain and diencephalon by anatomical–functional correlation. However, these factors are unlikely to explain the observed interactions in this study.

Fourth, the 4-week washout of antidepressants (binding to SERT) may have been too short [51]. Because all but one patient stopped antidepressants ≥6 months before scanning, we think no substantial bias in the BPND assessment was introduced by competitive binding by traces of previous antidepressants. Fifth, we allowed previous incidental use of illicit drugs (marijuana/cannabis in ten subjects, MDMA in one subject) in our controls. Because heavy use of MDMA (>50 MDMA tablets) can damage serotonin neurons [52], we performed an additional analysis in which we excluded data from the MDMA user in the control group. However, this exclusion did not affect our results (results available on request). Sixth, we did not check personal or family history of psychiatric illnesses among the controls, nor did we test for alcohol or drug abuse.

Conclusion

We showed lower SERT availability in the midbrain and diencephalon in depressed males and higher SERT availability in the diencephalon in depressed (nonsmoking) females compared with healthy controls. We confirmed a seasonal influence on midbrain SERT availability, and found a gender×smoking interaction in diencephalon SERT availability. This study points to complex effects of gender, smoking and season on the serotonergic system in the pathogenesis of MDD.

References

Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Cohen NL, Ravindran AV; CANMAT Depression Work Group. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. IV. Medications and other biological treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2001;46 (Suppl 1):38S–58S.

Ruhe HG, Mason NS, Schene AH. Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol Psychiatry 2007;12:331–59.

Owens MJ. Selectivity of antidepressants: from the monoamine hypothesis of depression to the SSRI revolution and beyond. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(Suppl 4):5–10.

Stockmeier CA. Involvement of serotonin in depression: evidence from postmortem and imaging studies of serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter. J Psychiatr Res 2003;37:357–73.

Innis R, Baldwin R, Sybirska E, Zea Y, Laruelle M, al Tikriti M, et al. Single photon emission computed tomography imaging of monoamine reuptake sites in primate brain with [123I]CIT. Eur J Pharmacol 1991;200:369–70.

Laruelle M, Baldwin RM, Malison RT, Zea-Ponce Y, Zoghbi SS, al Tikriti MS, et al. SPECT imaging of dopamine and serotonin transporters with [123I] β-CIT: pharmacological characterization of brain uptake in nonhuman primates. Synapse 1993;13:295–309.

Lehto S, Tolmunen T, Joensuu M, Saarinen PI, Vanninen R, Ahola P, et al. Midbrain binding of [123I]nor-β-CIT in atypical depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006;30:1251–5.

Malison RT, Price LH, Berman R, van Dyck CH, Pelton GH, Carpenter L, et al. Reduced brain serotonin transporter availability in major depression as measured by [123I]-2 β-carbomethoxy-3 β-(4-iodophenyl)tropane and single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1090–8.

Newberg AB, Amsterdam JD, Wintering N, Ploessl K, Swanson RL, Shults J, et al. 123I-ADAM binding to serotonin transporters in patients with major depression and healthy controls: a preliminary study. J Nucl Med 2005;46:973–7.

Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Huang YY, Simpson N, Arcement J, et al. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:52–8.

Staley JK, Sanacora G, Tamagnan G, Maciejewski PK, Malison RT, Berman RM, et al. Sex differences in diencephalon serotonin transporter availability in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2006;59:40–7.

Willeit M, Praschak-Rieder N, Neumeister A, Pirker W, Asenbaum S, Vitouch O, et al. [123I] β-CIT SPECT imaging shows reduced brain serotonin transporter availability in drug-free depressed patients with seasonal affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:482–9.

Joensuu M, Tolmunen T, Saarinen PI, Tiihonen J, Kuikka J, Ahola P, et al. Reduced midbrain serotonin transporter availability in drug-naive patients with depression measured by SERT-specific [123I] nor-β-CIT SPECT imaging. Psychiatry Res 2007;154:125–31.

Ahonen A, Heikman P, Kauppinen T, Koskela A, Bergström K. Serotonin transporter availability in drug free depression patients using a novel SERT ligand (abstract 106). Eur J Nucl Med 2004;31(Suppl 1):S227.

Catafau AM, Perez V, Plaza P, Pascual JC, Bullich S, Suarez M, et al. Serotonin transporter occupancy induced by paroxetine in patients with major depression disorder: a [123I]-ADAM SPECT study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:145–53.

Herold N, Uebelhack K, Franke L, Amthauer H, Luedemann L, Bruhn H, et al. Imaging of serotonin transporters and its blockade by citalopram in patients with major depression using a novel SPECT ligand [123I]-ADAM. J Neural Transm 2006;113:659–70.

Meyer JH, Houle S, Sagrati S, Carella A, Hussey DF, Ginovart N, et al. Brain serotonin transporter binding potential measured with carbon 11-labeled DASB positron emission tomography: effects of major depressive episodes and severity of dysfunctional attitudes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:1271–9.

Reivich M, Amsterdam JD, Brunswick DJ, Shiue CY. PET brain imaging with [11C](+)McN5652 shows increased serotonin transporter availability in major depression. J Affect Disord 2004;82:321–7.

Ichimiya T, Suhara T, Sudo Y, Okubo Y, Nakayama K, Nankai M, et al. Serotonin transporter binding in patients with mood disorders: a PET study with [11C]McN5652. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51:715–22.

Eggers B, Hermann W, Barthel H, Sabri O, Wagner A, Hesse S. The degree of depression in Hamilton rating scale is correlated with the density of presynaptic serotonin transporters in 23 patients with Wilson’s disease. J Neurol 2003;250:576–80.

Staley JK, Krishnan-Sarin S, Zoghbi S, Tamagnan G, Fujita M, Seibyl JP, et al. Sex differences in [123I]beta-CIT SPECT measures of dopamine and serotonin transporter availability in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. Synapse 2001;41:275–84.

Pirker W, Asenbaum S, Hauk M, Kandlhofer S, Tauscher J, Willeit M, et al. Imaging serotonin and dopamine transporters with [123I] β-CIT SPECT: binding kinetics and effects of normal aging. J Nucl Med 2000;41:36–44.

van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Seibyl JP, Laruelle M, Klumpp H, Zoghbi SS, et al. Age-related decline in central serotonin transporter availability with [123I] β-CIT SPECT. Neurobiol Aging 2000;21:497–501.

Buchert R, Schulze O, Wilke F, Berding G, Thomasius R, Petersen K, et al. Is correction for age necessary in SPECT or PET of the central serotonin transporter in young, healthy adults? J Nucl Med 2006;47:38–42.

Praschak-Rieder N, Willeit M, Wilson AA, Houle S, Meyer JH. Seasonal variation in human brain serotonin transporter binding. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:1072–8.

de Win MM, Habraken JB, Reneman L, van den Brink W, den Heeten GJ, Booij J. Validation of [123I]b-CIT SPECT to assess serotonin transporters in vivo in humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30:996–1005.

Verhoeff NP, Kapucu O, Sokole-Busemann E, Van Royen EA, Janssen AG. Estimation of dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in the striatum with iodine-123-IBZM SPECT: technical and interobserver variability. J Nucl Med 1993;34:2076–84.

Laruelle M, Vanisberg MA, Maloteaux JM. Regional and subcellular localization in human brain of [3H]paroxetine binding, a marker of serotonin uptake sites. Biol Psychiatry 1988;24:299–309.

Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1533–9.

Dahlstrom M, Ahonen A, Ebeling H, Torniainen P, Heikkila J, Moilanen I. Elevated hypothalamic/midbrain serotonin (monoamine) transporter availability in depressive drug-naive children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry 2000;5:514–22.

Meyer JH, Wilson AA, Ginovart N, Goulding V, Hussey D, Hood K, et al. Occupancy of serotonin transporters by paroxetine and citalopram during treatment of depression: a [11C]DASB PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1843–9.

Meyer JH. Imaging the serotonin transporter during major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2007;32:86–102.

Fink G, Sumner BE, McQueen JK, Wilson H, Rosie R. Sex steroid control of mood, mental state and memory. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1998;25:764–75.

Lu NZ, Eshleman AJ, Janowsky A, Bethea CL. Ovarian steroid regulation of serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) binding, distribution, and function in female macaques. Mol Psychiatry 2003;8:353–60.

Swaab DF, Bao AM, Lucassen PJ. The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev 2005;4:141–94.

McIntyre RS, Mancini D, Eisfeld BS, Soczynska JK, Grupp L, Konarski JZ, et al. Calculated bioavailable testosterone levels and depression in middle-aged men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006;31:1029–35.

Fink G, Sumner B, Rosie R, Wilson H, McQueen J. Androgen actions on central serotonin neurotransmission: relevance for mood, mental state and memory. Behav Brain Res 1999;105:53–68.

Best SE, Sarrel PM, Malison RT, Laruelle M, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, et al. Striatal dopamine transporter availability with [123I] β-CIT SPECT is unrelated to gender or menstrual cycle. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:181–9.

Neumeister A, Pirker W, Willeit M, Praschak-Rieder N, Asenbaum S, Brucke T, et al. Seasonal variation of availability of serotonin transporter binding sites in healthy female subjects as measured by [123I]-2 β-carbomethoxy-3 β-(4-iodophenyl)tropane and single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:158–60.

Buijs RM, Scheer FA, Kreier F, Yi C, Bos N, Goncharuk VD, et al. Organization of circadian functions: interaction with the body. Prog Brain Res 2006;153:341–60.

Pickard GE, Weber ET, Scott PA, Riberdy AF, Rea MA. 5HT1B receptor agonists inhibit light-induced phase shifts of behavioral circadian rhythms and expression of the immediate-early gene c-fos in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci 1996;16:8208–20.

Moore RY, Speh JC. Serotonin innervation of the primate suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res 2004;1010:169–73.

Kent JM, Coplan JD, Lombardo I, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Mawlawi O, et al. Occupancy of brain serotonin transporters during treatment with paroxetine in patients with social phobia: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]McN 5652. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:341–8.

Parsey RV, Kent JM, Oquendo MA, Richards MC, Pratap M, Cooper TB, et al. Acute occupancy of brain serotonin transporter by sertraline as measured by [11C]DASB and positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry 2006;59:821–8.

Kish SJ, Furukawa Y, Chang LJ, Tong J, Ginovart N, Wilson A, et al. Regional distribution of serotonin transporter protein in postmortem human brain: is the cerebellum a SERT-free brain region? Nucl Med Biol 2005;32:123–8.

Yang YK, Yeh TL, Yao WJ, Lee IH, Chen PS, Chiu NT, et al. Greater availability of dopamine transporters in patients with major depression – a dual-isotope SPECT study. Psychiatry Res 2008;162:230–5.

Heinz A, Jones DW, Zajicek K, Gorey JG, Juckel G, Higley JD, et al. Depletion and restoration of endogenous monoamines affects beta-CIT binding to serotonin but not dopamine transporters in non-human primates. J Neural Transm Suppl 2004;(68):29–38.

Praschak-Rieder N, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Carella A, Wei C, Ginovart N, et al. Effects of tryptophan depletion on the serotonin transporter in healthy humans. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:825–30.

Talbot PS, Frankle WG, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Suckow RF, Slifstein M, et al. Effects of reduced endogenous 5-HT on the in vivo binding of the serotonin transporter radioligand 11C-DASB in healthy humans. Synapse 2005;55:164–75.

Hummerich R, Reischl G, Ehrlichmann W, Machulla HJ, Heinz A, Schloss P. DASB – in vitro binding characteristics on human recombinant monoamine transporters with regard to its potential as positron emission tomography (PET) tracer. J Neurochem 2004;90:1218–26.

Strauss WL, Layton ME, Dager SR. Brain elimination half-life of fluvoxamine measured by 19F magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:380–4.

Reneman L, Booij J, de Bruin K, Reitsma JB, de Wolff FA, Gunning WB, et al. Effects of dose, sex, and long-term abstention from use on toxic effects of MDMA (ecstasy) on brain serotonin neurons. Lancet 2001;358:1864–9.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank patients and healthy subjects for their participation in the study. We thank general practitioners and psychiatric residents for appropriate referrals of patients. Staff members and technicians of the Department of Nuclear Medicine provided indispensable help in performing the SPECT scans. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Maartje M. de Win, MD, PhD, for her help in recruiting the healthy subjects. Dr. Jules Lavalaye, MD, PhD, helped in the initial design of this study. Mrs. Michelle L. Miller revised the text linguistically. Dr. Ruud M. Buijs, PhD, commented constructively on an earlier version of the manuscript. Henricus G. Ruhé received a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), program Mental Health, education of investigators in mental health (OOG; no. 100-002-002).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruhé, H.G., Booij, J., Reitsma, J.B. et al. Serotonin transporter binding with [123I]β-CIT SPECT in major depressive disorder versus controls: effect of season and gender. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36, 841–849 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-1057-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-1057-x