Abstract

Purpose

To study striatal dopamine D2 receptor availability in DYT11 mutation carriers of the autosomal dominantly inherited disorder myoclonus–dystonia (M–D).

Methods

Fifteen DYT11 mutation carriers (11 clinically affected) and 15 age- and sex-matched controls were studied using 123I-IBZM SPECT. Specific striatal binding ratios were calculated using standard templates for striatum and occipital areas.

Results

Multivariate analysis with corrections for ageing and smoking showed significantly lower specific striatal to occipital IBZM uptake ratios (SORs) both in the left and right striatum in clinically affected patients and also in all DYT11 mutation carriers compared to control subjects.

Conclusions

Our findings are consistent with the theory of reduced dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) availability in dystonia, although the possibility of increased endogenous dopamine, and consequently, competitive D2R occupancy cannot be ruled out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The identification of genes in the hereditary forms of dystonia, like the dystonia-plus syndrome myoclonus–dystonia (M–D), gives the opportunity to study the pathophysiology in a well-defined homogeneous group. M–D is an autosomal dominantly inherited disorder, clinically characterised by myoclonic jerks and dystonic postures or movements of the upper body, often combined with psychiatric disorders such as depression or anxiety [1]. The disorder usually becomes clinically manifest within the first two decades and is often responsive to alcohol. M–D is autosomal dominantly inherited and is frequently caused by mutations in the epsilon-sarcoglycan gene (SGCE) on chromosome 7q21 [2, 3]. The SGCE gene encodes a membrane protein that is detected in several parts of the brain, but of which the function is unknown. Penetrance of M–D is dependent on the parental origin of the disease allele due to the mechanism of maternal imprinting [4]. In many patients with the M–D phenotype, the known DYT11 mutations are lacking, suggesting the involvement of other genes and/or environmental factors [5]. One new M–D locus has been mapped recently to chromosome 18p11 in one family [6]. Furthermore, single mutations in the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) and DYT1 genes have been described in combination with SGCE mutations in two M–D families [7].

M–D is considered as a dystonia-plus syndrome. The pathophysiology of M–D is largely elusive, but dysfunction of the basal ganglia is thought to play a major role in the pathophysiology of dystonia [8, 9]. Neuronal models of dystonia propose hyperactivity of the direct putamen-pallidal pathway with reduced inhibitory output of the internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi) and subsequent increased thalamic input to the (pre-)motor cortex. Striatal dopaminergic dysfunction is implicated in this model [10]. A recent M–D mouse model using SGCE knockout mice supported the role of dopamine in M–D and showed significantly increased levels of dopamine and its metabolites in the affected mice [11].

Recent in vitro experiments suggested that torsinA, the defective product of DYT1 mutation-afflicted patients, may be involved in processing SGCE in the endoplasmatic reticulum [12, 13]. To our knowledge, no human autopsy studies reporting on D2R loss in dystonia are available.

D2R imaging studies in other types of dystonia, including idiopathic cervical dystonia and DYT1 dystonia, showed reduced in vivo striatal binding [14, 15]. Cervical dystonia patients showed a bilateral and significant reduction of striatal D2R binding. In a recent study on DYT1, [11C]raclopride PET was used to image D2R, and a decreased striatal D2R binding was described in both affected and non-affected DYT1 carriers [15]. Another [11C]raclopride PET study in dopa-responsive dystonia patients (DYT5) showed increased D2 receptor availability, possibly due to reduced competition by endogenous dopamine and/or a compensatory upregulation as a response to dopamine deficiency [16]. A D2R imaging study in nocturnal myoclonus suggested lower receptor availability [17]. A D2R imaging study in M–D will improve our understanding of dystonia and particularly of M–D.

To the best of our knowledge, no D2R imaging studies in DYT11 gene mutation carriers are available. We, therefore, examined in vivo striatal D2R availability with [123I]IBZM single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using the bolus/constant infusion technique [18] in clinically affected (CA) and non-affected (CNA) DYT11 mutation carriers and their age- and sex-matched controls.

Materials and methods

Patients and control subjects

Fifteen DYT11 mutation carriers, including 11 clinically affected DYT11 carriers (mean age 50 years, range 30–67 years), four clinically non-affected DYT11 carriers (mean age 39 years, range 20–52 years), and 15 age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers (mean age 42 years, range 26–55 years) were studied. Gene mutation carriers were recruited from four different pedigrees, ten of these carriers came from one pedigree. Patients were defined as clinically affected when signs of dystonia or myoclonus were detected on neurological examination (Table 1). The healthy volunteers were historical controls from other studies using an identical scanning protocol. None of these control subjects had a history of neuroleptic or other dopaminergic treatment. None of the volunteers had either a history or a family history of myoclonus or dystonia. Smoking was reported by two clinically affected (CA), two clinically non-affected (CNA) and eight control subjects. Psychiatric diagnoses (depression, anxiety and/or OCD symptoms) according to the DSM-IV criteria were made by a psychiatrist in four CA and none of the CNA subjects. Two of the CA subjects fulfilled the criteria for depression, one for anxiety disorder, and one for depression, anxiety disorder as well as OCD (Table 1). CA subjects were clinically scored using the Burke–Fahn–Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale (BFMDRS) [19] and the Unified Myoclonus Rating Scale (UMRS) [20]. The control group comprised of neurologically and psychiatrically normal subjects. Informed consent was obtained in all subjects and the study was approved by the local medical ethics committee. Smokers were instructed not to smoke during the study, as well as in the 6 h preceding the study.

Data acquisition

The selective D2R tracer [123I]IBZM ([123I]iodobenzamide; specific activity >200 MBq/nmol) was synthesised by Amersham Healthcare as described earlier [21]. Subjects received a potassium iodide solution to block thyroid uptake of free radioactive iodide. SPECT studies were performed using a 12-detector single-slice brain-dedicated scanner (Neurofocus 810, which is an upgrade of the Strichmann Medical Equipment) with a full-width at half-maximum resolution of approximately 6.5 mm, throughout the 20-cm field-of-view (http://www.neurophysics.com). After positioning of the subjects with the head parallel to the orbitomeatal line, axial slices parallel and upward from the orbitomeatal line to the vertex were acquired in 5-mm steps (3 min scanning time per slice, acquired in a 64 × 64 matrix). The energy window was set at 135–190 keV.

In all participants, approximately 100 MBq of [123I]IBZM was given intravenously as bolus, followed by continuous infusion of 25 MBq/h to achieve unchanging regional brain activity levels [18, 22]. Acquisition of the images was started 2 h after the bolus injection [23].

Data processing

Attenuation correction of all images was performed as described earlier [24]. Images were reconstructed in 3-D mode (http://www.neurophysics.com). These 3-D reconstructed images were then randomly numbered and analysed blindly by one observer (RJB). For quantification, a region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was performed. The analysis procedure was repeated after approximately 4 weeks to assess intra-observer variability. For analysis of striatal [123I]IBZM binding, the ratio of specific striatal to occipital binding (representing non-specific binding) was calculated by averaging four consecutive transverse slices, representing the most intense striatal binding. Standard templates with fixed ROIs (striatal and occipital volume 2.6 and 3.1 mL per ROI, respectively; so, e.g. total striatal volume assessed 8 × 2.6 = 20.8 mL) were manually placed on the striatum and occipital cortex (Fig. 1), and then the ratio of striatal to occipital binding (SOR) was calculated as follows: (total striatal binding − occipital binding)/occipital binding. Using the bolus/constant infusion technique, this ratio represents the BPND [24].

Statistical analysis

Variability between the two analyses was calculated according to the formula: Δ(SOR2 − SOR1)/mean (SOR1, SOR2). In addition, the intra-class correlation was calculated. Symmetry of the left and right SORs was calculated using a Wilcoxon signed ranks test. A Mann–Whitney analysis was used to assess the differences in age between groups. Mann–Whitney analyses were performed to assess differences between all mutation carriers (CA plus CNA) and control subjects, as well as between clinically affected DYT11 gene mutation carriers (CA) and their control subjects. To assess the independent effect of the BFMDRS and UMRS sum scores, linear regression was performed in the DYT11 mutation group. Finally, two multivariate linear models were constructed to assess the effect of left and right SOR, respectively, corrected for the possible effect of age and smoking. Even though there were no significant differences between groups regarding these variables, this was performed to increase accuracy. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 12.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of CA and CNA are summarised in Table 1. Eight CA inherited the mutation from their father. Three CA and all CNA inherited the mutated gene from their mother.

IBZM SPECT

Variability between the two analyses of the 3-D reconstructed images was 7.3% with an 86% intra-class correlation. Results of the second analysis are presented here.

No significant difference in age was found between groups (p = 0.2). No asymmetry between left SORs and right SORs was detected in any group (p > 0.05); median values and quartiles are given in Table 2.

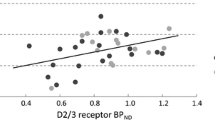

When the CA group was compared to the whole control group, differences for both SORs were found (left: p = 0.036, right: 0.041, mean = 0.032). In the full factorial multivariate analysis, after correcting for age and smoking, a difference was found for both left (p = 0.005), and the right SOR (p = 0.014). In this analysis, age was a significant covariate (p = 0.001), as well as smoking (p = 0.001). The adjusted R 2 of the whole model was 0.648.

Comparing the data of all DYT11 mutation carriers (both CA and CNA) to control subjects, a difference for the left SOR (p = 0.05), but not for the right SOR (p = 0.06), was found between the DYT11 carriers and controls. After correcting for age and smoking, the difference for both SORs (left: p = 0.003, right: p = 0.018) was significant.

In the linear regression analysis in the DYT11 mutation group, the clinical BFMDRS and UMRS scores did not correlate with the SOR (p = 0.716).

Discussion

In myoclonus–dystonia patients, a bilateral lower D2R binding in DYT11 gene mutation carriers was detected compared to control subjects. This effect was most robust in the clinically affected subjects compared to control subjects. Also, smoking and ageing were found to have an independent effect on striatal D2R binding.

The intra-observer variability and intra-class correlation are consistent with earlier publications on SPECT techniques [25] and suggest good reproducibility of the present results. Continuous infusion of the radioligand IBZM is an advantage of this study, thereby eliminating the possibility that the presently observed lower striatal binding ratios are due to differences, e.g. in cerebral blood flow between groups [18].

Reduced D2R binding is consistent with the theory of reduced D2R availability in dystonia [10]. An increased dopamine level may induce a downregulation of the D2R and may also induce an increased occupancy of D2R by endogenous dopamine [22]. Both phenomena may lead to the presently observed lower D2R binding. Our observation of reduced D2R binding in the clinically affected mutation carrier group and also in the whole DYT11 gene mutation carrier group may suggest similar, less extensive, abnormalities in the non-clinically affected group, although the number of non-clinically affected subjects is too small to draw firm conclusions. This would be consistent with a [11C]raclopride PET study investigating DYT1 CNA [15]. It is noteworthy, however, that the maternal imprinting mechanism as described in DYT11 is not responsible for reduced penetrance in DYT1 mutation carriers. Maternal imprinting implies to induce only abnormalities in mutation carriers inheriting the mutated allele from their father, as only wild-type paternal allele was detectable in cDNA in peripheral leucocytes [26, 27]. Larger groups of non-clinically affected DYT11 mutation carriers should be tested to investigate this matter. Clinically, the maternal imprinting is not complete. Three out of 11 CA, inheriting the gene from their mother, did show mild axial dystonia. This phenomenon has also been described in other M–D families [1, 27–29].

It remains unclear whether this D2R binding reduction is related to the dystonia, or also to the myoclonus, or possibly even the psychiatric symptoms. Regarding the psychiatric symptoms, three subjects of the CA group were diagnosed with recurrent episodes of depression, two were diagnosed with anxiety disorder and one was diagnosed with OCD. A D2R study using [123I]IBZM SPECT found no differences between depressed patients and controls [30], whilst another found increased D2R availability using [11C]raclopride PET [31]. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the results of the present study may be attributed to depression. Limited information is available on anxiety patients, only one study using [123I]IBZM SPECT suggested lower D2R availability in social phobia [32]. Due to the small number of OCD and anxiety patients in the current study, major effects are unlikely.

In our study, smoking turned out to be a significant covariate. Conflicting evidence exists on the effect of smoking on D2R expression and availability in smoking subjects. Although not found in a number of earlier studies [33–35], the effect of smoking on D2R availability has been described in another, very recent study [36].

Ageing effects on dopamine D2R in SPECT studies are well-described [37] and we could replicate this finding. The algorithm correcting for ageing effects we used in this study is based on a linear relation between D2R availability and age. Although this relation cannot be stated to be linear with certainty, groups were age-matched and analyses were done with and without this correction, both yielding significant results. Left–right asymmetry of striatal dopamine D2 receptors has been described in the literature [38], but was not detected in the present study.

A possible limitation of the current study is the fact that the spatial resolution of clinical SPECT studies is lower than that of PET. This prevents the possibility of adequately analysing putamen and caudate nucleus binding separately. However, separate analysis of binding in M–D patients will probably not provide much additional information. In an [11C]raclopride PET study in DYT1 patients (compared to controls), differences in binding in the whole striatum were similar to differences in binding in the caudate nucleus and putamen separately [15].

Another limitation might be that a large number of participants in the DYT11-positive group are related to each other. Although it cannot be stated with certainty that these subjects do not carry an additional mutation of the D2R, this seems highly unlikely.

Since none of the healthy volunteers had a history or a family history of myoclonus or dystonia, was aged above 26 and as M–D is an extremely rare affliction, it is very unlikely that a DYT11 mutation carrier was recruited into the control population [39]. However, since we have not determined the lack of this mutation in our control group, we cannot rule out with absolute certainty that all controls did not carry this mutation.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence for the presence of D2R binding abnormalities in DYT11 mutation carriers. Although further research is warranted, these findings may provide further insight in the pathophysiology of inherited forms of dystonia.

References

Zimprich A, Grabowski M, Asmus F, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding epsilon-sarcoglycan cause myoclonus–dystonia syndrome. Nat Genet 2001;29:66–9.

Klein C. Myoclonus and myoclonus–dystonias. In: Pulst SM, editor. Genetics of movement disorders. Boston: Academic; 2003. p. 449–69.

Asmus F, Gasser T. Inherited myoclonus–dystonia. Adv Neurol 2004;94:113–9.

Piras G El Kharroubi A, Kozlov S, et al. Zac1 (Lot1), a potential tumor suppressor gene, and the gene for epsilon-sarcoglycan are maternally imprinted genes: identification by a subtractive screen of novel uniparental fibroblast lines. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:3308–15.

Gerrits MC, Foncke EM, de Haan R, et al. Phenotype–genotype correlation in Dutch patients with myoclonus–dystonia. Neurology 2006;66:759–61.

Grimes DA, Han F, Lang AE, St George-Hyssop P, Rachaco L Bulman DE. A novel locus for inherited myoclonus dystonia on 18p11. Neurology 2002;59:1183–6.

Schule B, Kock N, Svetel M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in ten families with myoclonus–dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1181–5.

Marsden CD, Obeso JA, Zarranz JJ, Lang AE. The anatomical basis of symptomatic hemidystonia. Brain 1985;108:463–83.

Obeso JA, Gimenez-Roldan S. Clinicopathological correlation in symptomatic dystonia. Adv Neurol 1988;50:113–22.

Vitek JL. Pathophysiology of dystonia: a neuronal model. Mov Disord 2002;17(Suppl 3):S49–62.

Yokoi F, Dang MT, Li J, Li Y. Myoclonus, motor deficits, alterations in emotional responses and monoamine metabolism in epsilon sarcoglycan deficient mice. J Biochem 2006;140:141–6.

Breakefield XO, Blood AJ, Yuqing L, et al. The pathophysiological basis of dystonias. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:222–34.

Esapa CT, Waite A, Locke M, et al. SGCE missense mutations that cause myoclonus–dystonia syndrome impair epsilon-sarcoglycan trafficking to the plasma membrane: modulation by ubiquitination and torsinA. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16:327–42.

Naumann M, Pirker W, Reiners K, Lange KW, Becker G, Brucke T. Imaging the pre- and postsynaptic side of striatal dopaminergic synapses in idiopathic cervical dystonia: a SPECT study using [123I]epidepride and [123I]β-CIT. Mov Disord 1998;13:319–23.

Asanuma K, Ma Y, Okulski J, et al. Decreased striatal D2 receptor binding in non-manifesting carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Neurology 2005;64:347–9.

Rinne JO, Iivanainen M, Metsähonkala L, et al. Striatal dopaminergic system in dopa-responsive dystonia: a multi-tracer PET study shows increased D2 receptors. J Neural Transm 2004;111:59–67.

Staedt J, Stoppe G, Kogler A, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus syndrome (periodic limb movements in sleep) related to central dopamine D2-receptor alteration. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995;245:8–10.

Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, et al. SPECT imaging of striatal dopamine release after amphetamine challenge. J Nucl Med 1995;36:1182–90.

Burke RE, Fahn S, Marsden CD, Bressman SB, Moskowitz C, Friedman J. Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias. Neurology 1985;35:73–7.

Frucht SJ, Leurgans SE, Hallett M, Fahn S. The unified myoclonus rating scale. Adv Neurol 2002;89:361–37.

Costa DC, Verhoeff NP, Cullum ID, et al. In vivo characterisation of 3-iodo-6-methoxybenzamide 123I in humans. Eur J Nucl Med 1990;16:813–6.

Booij J, Korn P, Linszen DH, van Royen EA. Assessment of endogenous dopamine release by methylphenidate challenge using iodine-123 iodobenzamide single-photon emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med 1997;24:674–7.

Booij J, Tissingh G, Boer GJ, et al. [123I]FP-CIT SPECT shows a pronounced decline of striatal dopamine transporter labelling in early and advanced Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:133–40.

Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1533–9.

Booij J, Habraken JB, Bergmans P, et al. Imaging of dopamine transporters with iodine- 123-FP-CIT SPECT in healthy controls and patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Nucl Med 1998;39:1879–84.

Grabowski M, Zimprich A, Lorenz-Depiereux B, et al. The epsilon-sarcoglycan gene (SGCE), mutated in myoclonus–dystonia syndrome, is maternally imprinted. Eur J Hum Genet 2003;11:138–44.

Foncke EMJ, Gerrits MCF, van Ruissen F, et al. Distal myoclonus and late onset in a large Dutch family with myoclonus–dystonia. Neurology 2006;67:1677–80.

Asmus F, Zimprich A, Tezenas du Montcel S, et al. Myoclonus–dystonia syndrome: epsilon-sarcoglycan mutations and phenotype. Ann Neurol 2002;52:489–92.

Beukers RJ, Foncke EMJ, van der Meer J, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in myoclonus dystonia. Abstract in New Developments in Functional Research for Movement Disorders: Relevance for Clinical Practice. Amsterdam; 2006. p. 27.

Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Zae Ponce Y, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor availability and amphetamine induced dopamine release in unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:313–22.

Meyer JH, McNeely HE, Sagrati S, et al. Elevated putamen D2 receptor binding potential in major depression with motor retardation: an [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography study. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1594–602.

Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR, Abi-Dargham A, Lin SA, Laruelle M. Low dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:457–9.

Yang YK, Yao WJ, McEvoy JP, et al. Striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in male smokers. Psychiatry Res 2006;146:87–90.

Scott DJ, Domino EF, Heitzeg MM, et al. Smoking modulation of μ-opioid and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated neurotransmission in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007;32:450–7.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Begleiter H, et al. High levels of dopamine D2 receptors in unaffected members of alcoholic families: possible protective factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:999–1008.

Fehr C, Yakushev I, Hohmann N, et al. Association of low striatal dopamine D2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165(4):507–14.

Ichise M, Ballinger JR, Tanaka F, et al. Age-related changes in D2 receptor binding with iodine-123-iodobenzofuran SPECT. J Nucl Med 1998;39:1511–8.

Larisch R, Meyer W, Klimke A, et al. Left–right asymmetry of striatal dopamine D2 receptors. Nucl Med Commun 1998;19:781–7.

Grünewald A, Djarmati A, Lohmann-Hedrich K, et al. Myoclonus–dystonia: significance of large SGCE deletions. Hum Mutat 2008;29:331–2.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. EMJ Foncke for her help with the clinical evaluation of the patients. This study was supported by the following research grants: NWO-VIDI grant (project 016.056.333 to R.J.B. and M.A.J.T.) and ONWA (ABIP 2006-13).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the EANM congress in Copenhagen (October 2007).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Beukers, R.J., Booij, J., Weisscher, N. et al. Reduced striatal D2 receptor binding in myoclonus–dystonia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36, 269–274 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0924-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0924-9