Abstract

Recent developments in molecular biology and metabolic engineering have resulted in a large increase in the number of strains that need to be tested, positioning high-throughput screening of microorganisms as an important step in bioprocess development. Scalability is crucial for performing reliable screening of microorganisms. Most of the scalability studies from microplate screening systems to controlled stirred-tank bioreactors have been performed so far with unicellular microorganisms. We have compared cultivation of industrially relevant oleaginous filamentous fungi and microalga in a Duetz-microtiter plate system to benchtop and pre-pilot bioreactors. Maximal glucose consumption rate, biomass concentration, lipid content of the biomass, biomass, and lipid yield values showed good scalability for Mucor circinelloides (less than 20% differences) and Mortierella alpina (less than 30% differences) filamentous fungi. Maximal glucose consumption and biomass production rates were identical for Crypthecodinium cohnii in microtiter plate and benchtop bioreactor. Most likely due to shear stress sensitivity of this microalga in stirred bioreactor, biomass concentration and lipid content of biomass were significantly higher in the microtiter plate system than in the benchtop bioreactor. Still, fermentation results obtained in the Duetz-microtiter plate system for Crypthecodinium cohnii are encouraging compared to what has been reported in literature. Good reproducibility (coefficient of variation less than 15% for biomass growth, glucose consumption, lipid content, and pH) were achieved in the Duetz-microtiter plate system for Mucor circinelloides and Crypthecodinium cohnii. Mortierella alpina cultivation reproducibility might be improved with inoculation optimization. In conclusion, we have presented suitability of the Duetz-microtiter plate system for the reproducible, scalable, and cost-efficient high-throughput screening of oleaginous microorganisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

High-throughput screening (HTS) of microorganisms and cell cultures is an important step in the development of sustainable bioprocesses. Shake flasks have been the standard for screening of microbes, substrates, and growth conditions for a long time. Due to advances in metabolic engineering, the number of strains to be tested have increased significantly, making the throughput capacity of the shake flask cultures insufficient (Knudsen 2015; Silk et al. 2010). Recent developments in the miniaturization of fermentation systems have opened new opportunities in HTS, saving time and cost for bioprocess—and product development (Lübbehüsen et al. 2003). Microtiter plate-based systems (MTPS), with either 24-, 48-, or 96-well plates, are the most commonly used initial screening platform in biotechnology due to their simplicity, high throughput, good reproducibility, and automation possibilities (Long et al. 2014; Sohoni et al. 2012; Wu and Zhou 2014) It has been reported that the variability of extracellular metabolite production by filamentous microorganisms in MTPS is significantly lower than that in shake flasks (Linde et al. 2014; Siebenberg et al. 2010; Sohoni et al. 2012). Commercial HTS microtiter plate systems differ by monitoring and control options of process parameters (pH, DO, feeding, metabolites), throughput, instrument, and running cost (Long et al. 2014). Sophisticated, state-of-the-art MTPS with built-in optical sensors aim to mimic bioreactor cultivation environment. Good scalability has been reported in these systems up to 15 m3 bioreactors; however, most of these studies have been performed with unicellular microorganisms (bacteria and yeasts) (Back et al. 2016; Kensy et al. 2009; Knudsen 2015; Long et al. 2014; Lübbehüsen et al. 2003; Posch et al. 2013; Silk et al. 2010). Scalability of filamentous fungi from MTPS to bioreactors is rarely discussed and the few studies performed to date were performed at very a low substrate concentration (i.e., 5 g/L glucose) (Knudsen 2015). Application of optical online sensors in MTPS for the screening of filamentous fungi is problematic due to adherent wall growth and complex growth morphology. For these reasons, at/off-line bioprocess monitoring of filamentous fungi in MTPS is a more viable approach (Posch et al. 2013).

Duetz-MTPS is a simple and low-cost HTS system that consists of standard microplates (24, 48, or 96 wells) combined with a plate cover that enables sufficient gas transfer and prohibit extensive evaporation and cross-contamination of strains during cultivations (Duetz et al. 2000). The system offers very high throughput since MTPs can be stacked in a shaker. However, the system is considered less scalable due to a lack of control options and is therefore mainly used for initial strain selection based on end-point productivities (Long et al. 2014; Sohoni et al. 2012). In a recent study, we have evaluated the cultivation of Mucor circinelloides, Umbelopsis isabellina, and Penicillium glabrum oleaginous filamentous fungi in the Duetz-MTPS, resulting in good reproducibility and kinetics (Kosa et al. 2017).

The aim of the current study is to compare growth and lipid production of oleaginous microorganisms in Duetz-MTPS to controlled stirred-tank bioreactors. For this purpose, we selected the following oleaginous microorganisms: filamentous fungi Mucor circinelloides and Mortierella alpina, and heterotrophic microalga (marine dinoflagellate) Crypthecodinium cohnii. The selected microorganisms are producers of high-value polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as gamma-linolenic acid (GLA, C18:3n6), arachidonic acid (ARA, C20:4n6), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6n3) and have been used worldwide in nutraceutical products (Ratledge 2013). According to our knowledge, this is the first comparison of oleaginous microorganisms grown in Duetz-MTPS and in controlled stirred-tank bioreactors. We also show how Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy can be used in combination with the Duetz-MTPS for high-throughput characterization of oleaginous filamentous fungi and microalgae.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms

Mucor circinelloides VI 04473 was obtained from the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science (Oslo, Norway), while Mortierella alpina ATCC 32222 and Crypthecodinium cohnii ATCC 40750 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA).

Media and growth conditions

For inoculum preparation, filamentous fungi M. circinelloides and M. alpina were first cultivated on malt extract and potato dextrose agar, while dinoflagellate C. cohnii was maintained statically on an ATCC 2076 medium consisting of 4 g/L yeast extract (YE, Oxoid, Hampshire, England), 12 g/L glucose, and 25 g/L sea salts (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA). All cultures were incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. The inoculum medium for bioreactor experiments contained 40 g/L glucose—10 g/L YE for M. circinelloides, 20 g/L glucose—10 g/L YE for M. alpina, and ATCC 2076 medium for C. cohnii. 0.5- and 2-L shake flasks (baffled for fungi) were filled in with 150 and 625 mL inoculum media, respectively. Flasks were inoculated with fungal spores from Petri dishes or with 10 v/v% 7 days old C. cohnii seed culture and were grown at 25 °C for 2–4 days at shaking speed 100–150 rpm.

The lipid production media for M. circinelloides contained 80 g/L glucose and 3 g/L YE, for M. alpina it contained 60 g/L glucose and 10 g/L YE, while for C. cohnii, it consisted of 60 g/L glucose, 5 g/L YE, and 25 g/L sea salts. Fungal lipid production media also contained (g/L): KH2PO4 7, Na2HPO4 2, MgSO4.7H2O 1.5, CaCl2.2H2O 0.1, (from 1000× concentrated stock solution): FeCl3.6H2O 0.008, ZnSO4.7H2O 0.001, CoSO4.7H2O 0.0001, CuSO4.5H2O 0.0001, MnSO4.5H2O 0.0001 (Kavadia et al. 2001). Chemicals except YE were bought from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). In case of M. alpina, 3.5 g/L KH2PO4 and 1 g/L Na2HPO4 were used. The chemical composition of lipid production media was the same for all tested cultivation scales (Duetz-MTPS—2.5 mL, benchtop fermenter—1.5 L, and pilot scale fermenter—25 L). Demineralized water was used for media preparation in Duetz-MTPS and benchtop bioreactor, while tap water was used in the pre-pilot scale bioreactor. pH of production media after autoclaving were 6.6, 6.1, and 6.3 for C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina respectively and pH was only controlled in bioreactors. The evolution of pH in Duetz-MTPS cultivations can be found in Fig. S4.

Cultivations in Duetz-MTPS were performed in autoclaved 24-square polypropylene deep well MTPs (total volume per well 11 mL) with low evaporation version sandwich cover (Enzyscreen, Heemstede, Netherlands). All wells were filled in with sterile lipid production medium and were incubated with 10–250 μL fungal spore or microalga suspensions, resulting in 2.5 mL final volume. The final concentrations were 5·108 and 5·107 of spores/mL for M. circinelloides and M. alpina, respectively. For C. cohnii, the final concentration was 5·106 cells/mL. MTPS were incubated at 28 °C at 300 rpm (circular orbit 0.75″ or 19 mm) in an Innova 40R refrigerated desktop shaker (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 7–8 days, and each day, one plate was removed for the analysis of biomass and supernatant. To compare performance with bioreactor runs, the merged content of the wells was used, while reproducibility in MTPS were tested by measuring three individual wells.

The bioreactor cultivations were performed in 2.5 L total volume glass fermenter (Minifors, Infors, Bottmingen, Switzerland) and 42 L total volume stainless steel in situ sterilizable fermenter (Techfors-S, Infors) with working volumes of 1.5 and 25 L, respectively (working volumes are used for referring to benchtop and pre-pilot scale fermentations in the following). Autoclaved and in situ sterilized media were inoculated with 10 and 4 v/v% (in benchtop and pre-pilot bioreactors, respectively) of the abovementioned shake flask inoculums. Glucose and trace element solutions were sterilized separately from the YE-salts solution and combined afterwards (same procedure in Duetz-MTPS).

For mixing, the benchtop and pilot fermenter were equipped with two and three 6-blade Rushton turbines, respectively. Temperature for all cultivations was 28 °C. pH was monitored with a pH probe (Mettler-Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) and was kept at 6.0 for M. circinelloides, M. alpina and 6.5 for C. cohnii with the automatic addition of 1 M NaOH and 1 M H2SO4 (for fungi) or 1 M HCl (for microalga). Dissolved oxygen (DO) was monitored with Hamilton (Bonaduz, Switzerland) and Mettler-Toledo polarographic oxygen sensors (in 1.5 L and 25 L bioreactors) and was maintained above 20% of the saturation with the automatic control of stirrer speed (300–600 rpm or 100–600 rpm for microalga). Off-gas analysis was performed with a FerMac 368 (Electrolab Biotech, Tewkesbury, UK) and Infors gas analyzers connected to the off-gas condenser of the glass and stainless steel fermenters, respectively. Cultures were aerated through a sparger at 0.5 VVM for fungi (0.75 and 12.5 L/min) and 1.0 VVM (1.5 L/min) for the microalga. Foam was controlled via a foam sensor with five times diluted Glanapon DB 870 antifoam (Busetti, Vienna, Austria).

M. alpina and C. cohnii had two parallel runs in the glass fermenters, while in case of M. circinelloides, only a single run was performed in a 1.5 L bioreactor due to technical problems. The cultivation of microalga C. cohnii was performed in MTPS and glass bioreactors, but not in the pre-pilot bioreactor due to the corrosive nature of ATCC 2076 medium for stainless steel (Behrens et al. 2010; Hillig et al. 2013).

Microscopy

Micrographs were recorded with a DM6000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) in bright-field and fluorescence mode after Nile-red staining according to the previously described protocol (Kosa et al. 2017).

Optical density measurement

Optical density (OD) of C. cohnii was measured (after proper dilution) at 600 nm with a SPECTROstar Nano UV/Vis microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). A calibration of OD versus cell dry weight (g/L) was performed (Figure S3).

Preparation of fungal biomass for FTIR analysis and lipid extraction for GC fatty acid analysis

Fungal biomass from MTPS and 1.5 L cultivations were filtered through a Whatman No. I filter paper in a vacuum setup (GE Whatman, Maidstone, UK), while in case of the 25 L cultivations, a 75-μm aperture test sieve was used (Endecotts, London, UK) for biomass separation. After filtration, the fungal biomass was washed thoroughly with distilled water. In case of microalga C. cohnii, the biomass was separated from the medium by centrifugation at 3000 rpm and it was washed once with distilled water. In the next step, the fungal and algal biomass was frozen at − 20 °C and then was lyophilized overnight in an Alpha 1-2 LDPlus freeze-dryer (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany) at − 55 °C and 0.01 mbar pressure. The freeze-dried biomass was also used to calculate cell dry weight (CDW, g/L). Approximately 10 mg of freeze-dried biomass was transferred into 2-mL screw-cap tubes containing 500 μL distilled water and 250 ± 30 mg acid-washed glass beads (800 μm, OPS Diagnostics, Lebanon, USA). Biomass was then homogenized for 1–2 min in a FastPrep-24 high-speed benchtop homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, USA) at 6.5 m s−1. This homogenized fungal suspension was used for HTS-FTIR analysis. Lipid extraction protocol was performed according to previously described protocol (Kosa et al. 2017).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FTIR analysis of freeze-dried and homogenized fungal biomass was performed with the High-Throughput Screening eXTension (HTS-XT) unit coupled to the Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer (both Bruker Optik, Germany) in transmission mode (Kosa et al. 2017). Technical replicate spectra were averaged and then EMSC corrected (Kohler et al. 2005). For peak height determination second derivative (Savitzky-Golay, 2nd degree polynomial, 9 windows size) and EMSC correction were applied (Zimmermann and Kohler 2013). All pre-processing methods were performed using The Unscrambler X 10.5 (CAMO Software, Oslo, Norway).

GC-FID fatty acid analysis

Determination of lipid content of fungal biomass (FAME content) and fatty acid composition analysis were performed with a HP 6890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, USA) equipped with an SGE BPX70, 60.0 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm column (SGE Analytical Science, Ringwood, Australia) and flame ionization detector (FID) (Kosa et al. 2017). For identification and quantification of fatty acids, the C4-C24 FAME mixture (Supelco, St. Louis, USA), C13:0 tridecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and C23:0 tricosanoic acid (Larodan, Solna, Sweden) internal standards were used.

HPLC analysis

Glucose in the fermentation supernatant was quantified by using an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with RFQ-Fast Acid H + 8% (100 × 7.8 mm) column (Phenomenex, Torrance, USA) and coupled to a refractive index (RI) detector. Samples were filter sterilized and subsequently eluted using isocratic method at 1.0 mL/min flow rate in 6 min with 5 mM H2SO4 mobile phase at 85 °C column temperature.

Data analysis

Biochemical similarities between biomass samples were estimated using principal component analysis (PCA) of either GC or FTIR data. PCA data analysis was performed using The Unscrambler X 10.5 (CAMO Software, Oslo, Norway).

Results

Scalability of the cultivation of the three oleaginous model organisms, C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina from Duetz-MTPS to controlled stirred-tank bioreactors were evaluated based on the following characteristics: (a) cell morphology, (b) growth and substrate consumption rates, (c) biomass concentration and lipid content of biomass, and (d) fatty acid composition. The biochemical composition of cells were also measured by FTIR spectroscopy. In addition to scalability, the reproducibility of cultivations in Duetz-MTPS was investigated.

Morphology

The morphology of C. cohnii was similar in the MTPS and in the 1.5 L bioreactor: a combination of motile cells with two flagella and bigger static cells (Mendes et al. 2009) (Figure S1 a-b). The cells had a high number of oval starch granules (Deschamps et al. 2008), and towards the end of the fermentation circular lipid bodies (Fig. 1(a1, a2)). Micrographs of C. cohnii show that algal cells are sensitive to shear stress, resulting in cell bursting (Figure S1 c). M. circinelloides is a dimorphic fungus capable of growing both in filaments and yeast-like single cells, depending on environmental conditions (Lübbehüsen et al. 2003). In stirred bioreactors, the single cell form was more pronounced than in MTPS, probably caused by higher shear forces in the bioreactors (Figure S2). The predominant filamentous form looked similar at all tested scales, with different size (up to 15 μm) of lipid bodies in the hyphae (Fig. 1(b1, b2)). M. alpina also had similar morphology at all tested scales: fluffy pellets with a high number of small lipid bodies in the hyphae (max diameter 3 μm) (Fig. 1(c1, c2)).

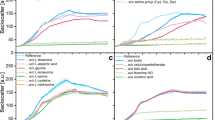

Glucose consumption and biomass production rates

Maximal glucose consumption rate was highest in the 1.5 L scale for the filamentous fungi (0.86 and 0.54 g/L/h for M. circinelloides and M. alpina, respectively) (Fig. 2). Maximal glucose consumption rate was the same in the MTPS and the 25 L bioreactor for M. circinelloides (0.72 g/L/h), while in case of M. alpina, it was higher in MTPS than in the 25 L bioreactor with 0.47—0.39 g/L/h. The dinoflagellate C. cohnii reached the same maximal glucose consumption rate in the MTPS and 1.5 L bioreactor (0.50 g/L/h). Comparison of biomass production rates between MTPS and bioreactors was only possible for C. cohnii due to significant wall growth of filamentous fungi M. circinelloides and M. alpina at all tested scales (Figure S5). Therefore, only the end-point biomass concentration of the fungi was measured from the bioreactor cultures. C. cohnii had the same maximal biomass production rate (0.11 g/L/h) in the MTPS and in the 1.5 L fermenter. The CO2 off-gas data from the bioreactor cultivations (show that after an exponential growth phase (10 h for M. circinelloides and 30 h for M. alpina), the cells entered into the stationary growth (i.e., lipid accumulation) phase (Figure S6). This is caused by the nitrogen depletion (approximately 1.5 and 5 g/L) from yeast extract. It is also visible from the growth and substrate consumption curves that M. alpina had 1 day longer lag phase in the MTPS than in the stirred bioreactors.

Biomass concentration and lipid content of biomass

Due to the long lag phase observed in the 1.5 L bioreactor runs with C. cohnii, the maximal biomass concentration was higher in the MTPS than in the glass bioreactor: 11.3 vs. 8.7 g/L (Fig. 3a). M. circinelloides reached comparable (14.4 and 15.8 g/L) end-point biomass concentrations in the MTPS and in the 1.5 L bioreactor (it was not measured at 25 L fermentation). The end-point biomass concentration of M. alpina in MTPS was higher than that in the 25 L bioreactor, but lower than that in the 1.5 L bioreactor: 21.5–24.5 ± 0 .5–16.9 g/L. Lipid content of C. cohnii increased during cultivations until glucose depletion, and reached significantly higher level in MTPS than in the glass bioreactor: 35.0 vs. 21.8 ± 3.0%. Oil content of M. circinelloides was above 20% already within the first 24–48 h in all tested scales (nitrogen source depleted at 10 h), and then, it increased only moderately in the following days with maximal values of 29.9–27.3—27.0% in MTPS, 1.5, and 25 L bioreactor runs, respectively. M. alpina started to accumulate lipids later than M. circinelloides due to the longer growth phase and higher nitrogen level in the medium (initial YE level was 10 g/L instead of 3 g/L). Maximal lipid content values of M. alpina were comparable across the tested scales: 36.4–42.4 ± 0.4–36.4% in MTPS, 1.5, and 25 L bioreactors.

Comparison of physiological fermentation parameters of C. cohnii, M. circinelloides and M. alpina in Duetz-MTPS, 1.5 L bioreactor and 25 L bioreactor. (a) Biomass, total lipid, total high-value PUFA (DHA, GLA and ARA for C. cohnii, M. circinelloides and M. alpina) [g/L]. (b) Biomass yield on glucose, lipid yield on glucose [g/g]

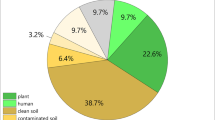

Fatty acid composition of single cell oil

The fatty acid composition of C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina biomass is summarized in the PCA scores plot of the GC data (Figure S7). C. cohnii is characterized by high content of C12:0, C14:0, C16:0 and C22:6n3 (DHA) and separated from the fungal oils on PC1 axis, while PC2 separates M. circinelloides from M. alpina. The separation of fungal oil composition is based on the presence/absence of C20 fatty acids (C20:3n6 DGLA and C20:4 ARA) and the relative amount of monounsaturated fatty acids (C16:1n7, C18:1n9c) in the oil. Maximum DHA content of the oil in C. cohnii microalga cells was 52.6 ± 4.3% in the bioreactor and 46.3% in MTPS (it increased from 42.9% after glucose depletion) (Table 1). It has been shown that C. cohnii has a high oxygen demand for growth and synthesis of highly unsaturated PUFA such as DHA (Hillig 2014). This is in agreement with our results since the oil of the microalga grown in the bioreactor—where the aeration is more effective than in Duetz-MTPS—contained more unsaturated fatty acids, (C18:1n9, C22:6n3 DHA) and less C14:0. In the case of M. circinelloides, the FA composition of the fungal oil matched very good in the MTPS and the 1.5 L bioreactor, while in 25 L bioreactor, the GLA content of oil was found to be higher (15.0% vs. 10.0%) (Table 2). Lipid content and fatty acid composition of the wall-grown fungi from the 1.5 L bioreactors was investigated, and it was found to be very similar to the submerged biomass (Table S2). The ARA content in M. alpina oil (42.0–35.3 ± 3.0–34.4%) showed a good match at different scales (Table 3); however, major differences were found in the oleic acid (C18:1n9) content between scales (11.7–24.8 ± 3.7–17.3%). Similar to M. circinelloides, the lipid content and composition of the wall-grown M. alpina biomass was very similar to the submerged biomass (Table S3).

FTIR analysis of C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina biomass

Microalgal and fungal biomass were also analyzed by high-throughput FTIR spectroscopy. The most obvious change in mid-IR spectra of microalga and filamentous fungi during the bioprocesses was the increase of lipid-related peak intensities (Fig. 4). The C=O ester peak height at 1745 cm−1 in the mid-IR spectra was used to monitor lipid accumulation during cultivations, and these curves correlated well with reference curves for lipid content of biomass, obtained by the GC analyses. It is worth mentioning that the peak at approximately 3010 cm−1, which is related to =C–H stretching, correlates with the unsaturation level of single cell oil. The peak position was at 3014 cm−1 for C. cohnii (unsaturation index, UI = 2.86), 3012 cm−1 for M. alpina (UI = 1.93), and 3008 cm−1 for M. circinelloides (UI = 1.24). PCA results of FTIR data (Figure S8) confirm that biomass composition correlated well between different scales in case of M. circinelloides and M. alpina, while C. cohnii cultivation was less scalable from MTPS to 1.5 L bioreactors.

Reproducibility in Duetz-MTPS

The reproducibility of C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina cultivations in MTPS were evaluated based on the fermentation results achieved in three individual wells of the same MTP (Table 4). C. cohnii and M. circinelloides showed good reproducibility after 8 and 7 days of cultivations with less than 15% coefficient of variation for all measured parameters (glucose consumption, fatty acid composition, pH, biomass concentration, and lipid content of the biomass), while in case of M. alpina the variations were higher.

Discussion

C. cohnii had a much shorter lag phase in the MTPS than in the bioreactor (Fig. 2a) and it reached a substantially higher biomass concentration and lipid content than that in the stirred-tank bioreactor. Since the inoculation ratio was same at both scales (10 v/v%, OD600nm = 4) this might be the consequence of high shear stress in the bioreactor, caused by the agitation on the cells (stirrer speed maximum was 530 rpm). Nonetheless, different inocula were used for the MTP and the bioreactor; therefore, no clear conclusion can be drawn. Hillig et al. cultivated C. cohnii in a 24-deepwell plate together with perfluorodecalin (PFD) in order to avoid (reduce) oxygen limitation. An OD (optical density) value of 17 with PFD compared to 13 without PFD was measured, while in our study, an OD of 31.6 was reached. Moreover, in the study by Hillig et al., addition of water to deepwell plates had to be applied during the long cultivation of C. cohnii, in order to compensate for the severe evaporation loss. In Duetz-MTPS, the evaporation rate is very low (16 μl/well/day at 30 °C, 50% humidity) (Enzyscreen); therefore, addition of water was not necessary in our study. The values achieved in the Duetz-MTPS with C. cohnii are promising in comparison with industrial requirements (CDW > 10 g/L, DHA in oil > 20%, total DHA > 1.5 g/L) (Kyle et al. 1998).

Oxygen transfer rate (OTR) was about 30 mmol O2 L/h with the applied settings in the Duetz-MTPS (Enzyscreen), which corresponds to a mass transfer coefficient (kLa) of approximately 150 1/h. This value is within the range (kLa of 100–300 1/h) that is typical for aerated, stirred-tank bioreactors (Duetz et al. 2000). Comparing the biomass, lipid content of biomass and fatty acid composition of the oil achieved in Duetz-MTPS and in bioreactors, it can be assumed that oxygen limitation was not an issue during microtiter plate cultivations of C. cohnii, M. circinelloides, and M. alpina oleaginous microorganisms.

For a better comparison of fermentation kinetics (Fig. 2 and Table S4) with filamentous fungi at different scales, a unified inoculation approach should have been applied (i.e., inoculation with spores and same final spores concentration).

The reproducibility results in the Duetz-MTPS can be explained by the difference in morphology between strains. Cell and spore suspension inocula were homogenous and easy to pipette in the case of C. cohnii and M. circinelloides, while the M. alpina inoculum in addition to spores also contained mycelium that made it difficult to transfer inoculum equally into each well. It is likely that separation (filtration) of mycelium fragments from spores or fragmentation of mycelium for M. alpina inoculation can decrease the observed variability in Duetz-MTPS cultivation (Knudsen 2015; Sohoni et al. 2012). The growth morphology of M. alpina is in the form of fluffy pellets of different sizes, and this can also negatively affect the reproducibility in the Duetz-MTPS. In order to reduce this effect, glass beads can be added to the cultivation. For example, Sohoni et al. observed for Streptomyces coelicor that the addition of 3 mm glass beads prevented both pellet morphology and wall growth, improving reproducibility and scalability from MTP to benchtop bioreactor (Sohoni et al. 2012). Another strategy to induce dispersed growth of filamentous fungi is the addition of carboxypolymethylene, an anionic polymeric additive to the medium (Knudsen 2015). Despite these issues, the fatty acid composition of all the tested microorganisms showed excellent reproducibility in the Duetz-MTPS (Table S1-S3).

In conclusion, key fermentation physiological parameters (glucose consumption rate, biomass concentration, lipid content of the biomass, biomass, and lipid yield) were comparable (max 30% difference) for the oleaginous fungi M. circinelloides and M. alpina in the Duetz-MTPS and benchtop or pre-pilot stirred-tank bioreactors (600–10,000× volumetric scale factors). This has been achieved despite the absence of control options, such as pH and DO, in the Duetz-MTPS, and the difficult fungal growth characteristics, such as severe wall growth. However, the heterotrophic microalga C. cohnii reached a significantly higher biomass and lipid concentration in the MTPS than in the 1.5 L bioreactor, probably due to shear force sensitivity of this species. It is worth mentioning that the screening throughput of oleaginous microorganisms in the Duetz-MTPS can be increased by combining at-line FTIR spectroscopy and the automation of the cultivation-analytical system (Li et al. 2016). Reproducibility and scalability results demonstrated that the Duetz-MTPS can be used for the cost-efficient, high-throughput screening of both single-cell and multicellular oleaginous microorganisms.

References

Back A, Rossignol T, Krier F, Nicaud J-M, Dhulster P (2016) High-throughput fermentation screening for the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica with real-time monitoring of biomass and lipid production. Microb Cell Factories 15(1):147

Behrens PW, Thompson JM, Apt K, Pfeifer JW, Wynn JP, Lippmeier JC, Fichtali J, Hansen J (2010) Method to reduce corrosion during fermentation of microalgae. Google Patents

Deschamps P, Guillebeault D, Devassine J, Dauvillée D, Haebel S, Steup M, Buléon A, Putaux J-L, Slomianny M-C, Colleoni C (2008) The heterotrophic dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii defines a model genetic system to investigate cytoplasmic starch synthesis. Eukaryot Cell 7(5):872–880

Duetz WA, Rüedi L, Hermann R, O'Connor K, Büchs J, Witholt B (2000) Methods for intense aeration, growth, storage, and replication of bacterial strains in microtiter plates. Appl Environ Microbiol 66(6):2641–2646

Enzyscreen List sandwich covers for 24 well MTPs. Publisher. http://www.enzyscreen.com/sandwich_covers_24_mtps.htm. Accessed 10 Oct 2017

Enzyscreen Oxygen transfer rates. Publisher. http://www.enzyscreen.com/oxygen_transfer_rates.htm. Accessed 10 Oct 2017

Hillig F (2014) Impact of cultivation conditions and bioreactor design on docosahexaenoic acid production by a heterotrophic marine microalga—a scale up study. TU Berlin

Hillig F, Annemüller S, Chmielewska M, Pilarek M, Junne S, Neubauer P (2013) Bioprocess development in single-use systems for heterotrophic marine microalgae. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 85(1–2):153–161

Kavadia A, Komaitis M, Chevalot I, Blanchard F, Marc I, Aggelis G (2001) Lipid and γ-linolenic acid accumulation in strains of Zygomycetes growing on glucose. J Am Oil Chem Soc 78(4):341–346

Kensy F, Engelbrecht C, Büchs J (2009) Scale-up from microtiter plate to laboratory fermenter: evaluation by online monitoring techniques of growth and protein expression in Escherichia coli and Hansenula polymorpha fermentations. Microb Cell Factories 8(1):68

Knudsen PB (2015) Development of scalable high throughput fermentation approaches for physiological characterisation of yeast and filamentous fungi. Technical University of Denmark (DTU)

Kohler A, Kirschner C, Oust A, Martens H (2005) Extended multiplicative signal correction as a tool for separation and characterization of physical and chemical information in Fourier transform infrared microscopy images of cryo-sections of beef loin. Appl Spectrosc 59(6):707–716

Kosa G, Kohler A, Tafintseva V, Zimmermann B, Forfang K, Afseth NK, Tzimorotas D, Vuoristo KS, Horn SJ, Mounier J (2017) Microtiter plate cultivation of oleaginous fungi and monitoring of lipogenesis by high-throughput FTIR spectroscopy. Microb Cell Factories 16(1):101

Kyle DJ, Reeb SE, Sicotte VJ (1998) Dinoflagellate biomass, methods for its production, and compositions containing the same. Google Patents

Li J, Shapaval V, Kohler A, Talintyre R, Schmitt J, Stone R, Gallant AJ, Zeze DA (2016) A modular liquid sample handling robot for high-throughput fourier transform infrared spectroscopy advances in reconfigurable mechanisms and robots II. Springer, Berlin, pp 769–778

Linde T, Hansen N, Lübeck M, Lübeck PS (2014) Fermentation in 24-well plates is an efficient screening platform for filamentous fungi. Lett Appl Microbiol 59(2):224–230

Long Q, Liu X, Yang Y, Li L, Harvey L, McNeil B, Bai Z (2014) The development and application of high throughput cultivation technology in bioprocess development. J Biotechnol 192:323–338

Lübbehüsen TL, Nielsen J, McIntyre M (2003) Morphology and physiology of the dimorphic fungus Mucor circinelloides (syn. M. racemosus) during anaerobic growth. Mycol Res 107(2):223–230

Mendes A, Reis A, Vasconcelos R, Guerra P, da Silva TL (2009) Crypthecodinium cohnii with emphasis on DHA production: a review. J Appl Phycol 21(2):199–214

Posch AE, Herwig C, Spadiut O (2013) Science-based bioprocess design for filamentous fungi. Trends Biotechnol 31(1):37–44

Ratledge C (2013) Microbial production of polyunsaturated fatty acids as nutraceuticals. Microbial production of food ingredients, enzymes and nutraceuticals. http://www.elsevier.com/books/microbial-production-of-food-ingredientsenzymes-and-nutraceuticals/unknown/978-0-85709-343-1

Siebenberg S, Bapat PM, Lantz AE, Gust B, Heide L (2010) Reducing the variability of antibiotic production in Streptomyces by cultivation in 24-square deepwell plates. J Biosci Bioeng 109(3):230–234

Silk N, Denby S, Lewis G, Kuiper M, Hatton D, Field R, Baganz F, Lye GJ (2010) Fed-batch operation of an industrial cell culture process in shaken microwells. Biotechnol Lett 32(1):73

Sohoni SV, Bapat PM, Lantz AE (2012) Robust, small-scale cultivation platform for Streptomyces coelicolor. Microb Cell Factories 11(1):9

Wu T, Zhou Y (2014) An intelligent automation platform for rapid bioprocess design. J Lab Autom 19(4):381–393

Zimmermann B, Kohler A (2013) Optimizing Savitzky–Golay parameters for improving spectral resolution and quantification in infrared spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc 67(8):892–902

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Line Degn Hansen for the help in performing the 25 L fermentations.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (BIONÆR grant, project numbers 234258, 268305, and 227356, and FMETEKN grant, project number 257622).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the research idea: BZ. Designed the experiments: GK. Methodology: GK. Performed the experiments: GK, KV. Discussed the results: GK, BZ, KV, SJH, VS, NKA, AK. Analyzed the data: GK. Wrote the manuscript: GK. Discussed and revised the manuscript: GK, BZ, KV, SJH, VS, NKA, AK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 1.02 mb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosa, G., Vuoristo, K.S., Horn, S.J. et al. Assessment of the scalability of a microtiter plate system for screening of oleaginous microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102, 4915–4925 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-8920-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-8920-x