Abstract

Background

Very preterm birth can disturb brain maturation and subject these high-risk children to neurocognitive difficulties later.

Objective

The aim of the study was to evaluate the impact of prematurity on microstructure of frontostriatal tracts in children with no severe neurologic impairment, and to study whether the diffusion tensor imaging metrics of frontostriatal tracts correlate to executive functioning.

Materials and methods

The prospective cohort study comprised 54 very preterm children (mean gestational age 28.8 weeks) and 20 age- and gender-matched term children. None of the children had severe neurologic impairment. The children underwent diffusion tensor imaging and neuropsychological assessments at a mean age of 9 years. We measured quantitative diffusion tensor imaging metrics of frontostriatal tracts using probabilistic tractography. We also administered five subtests from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, Second Edition, to evaluate executive functioning.

Results

Very preterm children had significantly higher fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values (P<0.05, corrected for multiple comparison) in dorsolateral prefrontal caudate and ventrolateral prefrontal caudate tracts as compared to term-born children. We found negative correlations between the diffusion tensor imaging metrics of frontostriatal tracts and inhibition functions (P<0.05, corrected for multiple comparison) in very preterm children.

Conclusion

Prematurity has a long-term effect on frontostriatal white matter microstructure that might contribute to difficulties in executive functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The survival of infants born before 32 weeks of gestation has increased remarkably in the last 20 years. Neurologic outcomes have improved, as well, including a decreasing rate of major neurosensory disabilities such as cerebral palsy [1]. Despite this, children born at a very low gestational age (VLGA) continue to have difficulties in neurocognitive processing through their early school years and into adulthood [2,3,4], even with no serious perinatal brain injury [5]. Specific neurodevelopmental deficits, including problems in executive functioning, might explain poorer academic performance in this high-risk population [6].

Executive functions comprise cognitive processes such as attentional control, inhibition, shifting, working memory, reasoning and problem-solving. The prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal tracts are part of a wide neural network that conveys these processes [7, 8]. Among cortical areas, the frontal cortex has the longest maturational time window [9], making it particularly susceptible to both structural and functional alterations.

Very preterm birth might affect myelination and axonal growth in developing white matter. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a special sequence of MRI used to study white matter microstructure [10]. Fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, radial diffusivity and mean diffusivity are quantitative measures of water diffusion. These DTI metrics offer the opportunity to study possible correlations between voxel-based changes in white matter microstructure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born very preterm [11].

As part of our follow-up study, a cohort of VLGA children and a comparison group of term children underwent DTI and neuropsychological assessments at 9 years of age. Previously, we showed that VLGA children at school age had more problems in executive functions when compared to term children [3]. In the present study, we defined frontostriatal tracts using probabilistic tractography and quantitated DTI metrics. Our aim was to test the hypotheses that the DTI metrics of frontostriatal tracts differ between VLGA and term-born schoolchildren and that these microstructural properties correlate to executive functioning among schoolchildren born very preterm.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The present study was part of a prospective follow-up cohort study of children born before 32 weeks of gestation at Oulu University Hospital between November 1998 and November 2002. The data set of this population has been described in detail [3, 12]. The VLGA children underwent serial brain US examinations during the neonatal period, and severe brain injury was identified as intraventricular haemorrhage Grades 3 or 4 [13] or cystic periventricular leukomalacia [14]. A group of age- and gender-matched term children was selected from the birth register of Oulu University Hospital at the age of 9. The recruitment and inclusive follow-up assessments were carried out during a 4-year period, between November 2007 and November 2011, at Oulu University Hospital [3, 12].

Altogether, 68 VLGA children and 23 term children underwent brain MRI at a mean age of 9 years (range 8.6–9.6 years). Fourteen VLGA children were excluded from the current study. The exclusion criteria were cerebral palsy (n=4), missing DTI data (n=1), problems in MRI data transfer (n=2) or with quality control criteria (n=5), and technical problems in fibre tracking (n=2). Three term children were excluded: two because of missing DTI data and one because of technical problems in fibre tracking. Five parents of VLGA children refused to participate in neuropsychological tests, leaving 49 VLGA children and 20 term children with results from neuropsychological assessments at a mean age of 9 years (range 8.7–9.3 years). The ethics committee of Oulu University Hospital approved the study (reference number 60/2007), and we obtained written informed consent from both the participating children and their parents.

Neurologic and neuropsychological assessments

Severe neurologic impairment was defined as cerebral palsy. Among the VLGA children, cerebral palsy was confirmed by a child neurologist at Oulu University Hospital at the age of 5 years. The diagnosis was based on standard criteria by the Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe network [15]. Every child participating in the current study also underwent a structured neurologic assessment at the age of 9 years. None of the term children was diagnosed to have cerebral palsy. All participants attended mainstream school.

Neuropsychological assessments were performed by a child psychologist at Oulu University Hospital. The children completed 14 subtests from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, Second Edition [16]. Standardised scores were calculated and analysed for these subtests. The subtest scores, with a range of 1–19, had a normed mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3. The five subtests describing executive functioning —auditory attention, response set, inhibition/naming, inhibition/inhibition and inhibition/switching — were chosen for the present study from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, Second Edition. To reduce the number of outcome variables, we further calculated mean scores for attention domain (comprising auditory attention and response set subtests) and for inhibition domain (comprising three inhibition subtests). Four VLGA children and one term child could not perform the inhibition/switching subtest, leaving 45 VLGA children and 19 term children with no severe neurologic impairment and with results from the inhibition domain.

Neuroimaging

Conventional MRI was performed using a 1.5-tesla (T) GE Signa HDX (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The study protocol comprised a T1-weighted sagittal spin-echo sequence. For this protocol, the slice thickness was 5 mm with a 1-mm gap between slices, the field of view was 24 cm with a 512×512 matrix, and the repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) was 540/14 ms. In addition, T2-weighted axial images were taken using the Propeller technique with a slice thickness of 5 mm and a 1-mm gap, an echo train length of 28, a reconstruction diameter of 22 cm with a 512×512 matrix, and a TR/TE of 5,000/173 ms.

DTI was obtained using a spin-echo echoplanar sequence with an isotropic 3-mm voxel, 40 directions and a b value of 1,000. The repetition time was 9,000 ms, and the echo time was as short as possible. The slice thickness was 3 mm, and the field of view was 19.2 cm with a 64×64 matrix.

We used an 8-channel head coil. The child’s head was surrounded by soft cushions during scanning, and ear plugs were used to protect the child from imaging noise. No sedation was used during imaging. Data quality control was carried out with DTIPrep (Universities of North Carolina, Iowa and Utah, USA) [17]. Data were checked for slice-wise and interlace-wise intensity differences. Eddy current and motion defects were corrected, and data were checked gradient-wise for residual motion or deformations. Gradient directions that had image artefacts were removed from the data.

Probabilistic tractography was carried out using the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB) Diffusion Toolbox version 3.0 (FMRIB Analysis Group, Oxford, UK), which allowed for an estimation of the most probable pathway location from a seed point using Bayesian techniques [18]. Fibre tracking was initiated from all voxels within the seed masks to generate 5,000 streamline samples, each with a step length of 0.5 mm and a curvature threshold of 0.2.

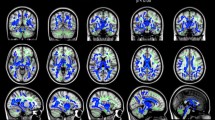

The frontostriatal fibres were divided into four bundles using a regions-of-interest approach. We used a connectivity-based seed classification analysis to identify connections among the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (Fig. 1). The cortex areas were used as seed masks. The caudate nucleus was used as a waypoint and a stop mask. Connections were analysed bilaterally. The contralateral hemisphere, ipsilateral putamen and thalamus were used as avoid masks. Masks were constructed using MARINA software (Bender Institute of Neuroimaging, University of Giessen, Germany) [19] and were originally defined in the Montréal Neurological Institute space and later transformed to diffusion space using FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool with default settings.

T1-weighted MR images with an overlay of the frontostriatal tracts coded by colours in a 9.1-year-old healthy boy (a control) who had normal findings at conventional MRI. a Sagittal. b Coronal. c Axial. The dorsolateral prefrontal caudate tract is red, the medial prefrontal caudate tract is blue, the orbitofrontal caudate tract is yellow and the ventrolateral prefrontal caudate tract is green

Voxel values represented the number of samples passing through any given voxel. Connectivity distribution was normalised using the waytotal value. To remove voxels with very low connectivity, we applied a probability threshold using values selected from the normalised connectivity distribution. The robust intensity range was used to read the two percentile values from healthy controls. The mean of these values was calculated and used as a threshold of the normalised connectivity distribution. The threshold varied among the tracts. The created image was binarised and used as a mask to collect fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity and radial diffusivity values from each child in the study cohort.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Differences in the averaged DTI values (fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity and radial diffusivity) in each tract and in both sides between VLGA and term-born children were evaluated using the Student’s t-test. Linear regression analyses were conducted to adjust these results with gender and perinatal brain injury. Effect sizes were calculated in terms of Hedges’s g using means and standard deviations [20]. A commonly used interpretation is to refer to effect sizes as 0.20, 0.50 and 0.80 for small, medium and large, respectively. We evaluated differences in the composite scores of attention and inhibition domains between VLGA and term-born children using the Student’s t-test. Further, we performed linear regression analyses to evaluate correlations between executive function scores and DTI values among VLGA children while controlling for gestational age, gender and perinatal brain injury. We controlled for inflation of Type I error by reducing the number of comparisons; only DTI values and executive function scores that differed significantly between the VLGA and term children were included in these analyses. The results were controlled for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method developed by Benjamini and Hochberg [21]. The level of significance was set at P<0.05, two-tailed.

Results

Antenatal and neonatal clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Four VLGA children had severe perinatal brain injury. The VLGA children were found to have significantly higher fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values in the left and right dorsolateral prefrontal caudate tracts and in the left and right ventrolateral prefrontal caudate tracts then the term children (Table 2). These results remained significant after controlling for gender and perinatal brain injury using linear regression analyses and after correcting for multiple comparisons. There were no significant differences in radial diffusivity and mean diffusivity values between the groups (data not shown). VLGA children had a 1.4-point (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.4–2.4; P=0.005) reduction in inhibition domain scores compared with term children. No significant differences were found in attention domain scores between the groups (P=0.341).

Correlations between inhibition domain scores and DTI metrics (fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values) in the left and right dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal caudate tracts among VLGA children were assessed using linear regression analyses. High fractional anisotropy values in these tracts correlated with low inhibition domain scores. In addition, high axial diffusivity values in the right dorsolateral prefrontal caudate tract correlated with low inhibition scores. The results remained significant after adjusting for gestational age, gender and perinatal brain injury and after correcting for multiple comparisons (Table 3).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, this study showed microstructural differences in the frontostriatal tracts between VLGA children with no severe neurologic impairment and term children at 9 years of age. The VLGA children had significantly higher fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values in two frontostriatal tracts bilaterally — dorsolateral prefrontal caudate and ventrolateral prefrontal caudate — than did the term children. Further, fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values in these tracts correlated negatively with neuropsychological test scores measuring inhibition, one of the core executive functions, in the VLGA children.

Functional and structural neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that during its maturational process the prefrontal cortex (including the dorsolateral prefrontal, medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal and ventrolateral prefrontal) forms connections within itself and with other cortical and subcortical brain regions [7]. Despite this widespread neural circuitry, prefrontal cortex and its frontostriatal network are still thought to play a major role in guiding processes required for flexible and goal-directed behaviours [7, 8, 22]. Preterm birth is associated with both reorganization and disruptions in cortical–cortical and cortical–subcortical connectivity [23].

Commonly, fractional anisotropy values have been found to increase during white matter maturation, reflecting myelination, more organised axons, and thus restricted water diffusion [24], in most cases with preterm children having lower values compared to term-born controls [25]. The present study found higher fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values in two frontostriatal tracts bilaterally in VLGA children compared to term children. Supporting our findings, recent studies have also found higher fractional anisotropy values in certain white matter pathways among different age groups of individuals born preterm [26,27,28,29,30]. A meta-analysis, based on 13 studies and including participants from children to young adults born preterm, identified four regions of increased fractional anisotropy and 11 regions of decreased fractional anisotropy in preterm subjects compared to term controls [25]. In addition to our study, others have reported higher axial diffusivity values in certain white matter regions, including the reticular activating system involved in attention abilities [31], among preterm individuals compared to term-born controls [27, 29, 30].

One explanation for the variability of fractional anisotropy among studies might be the differences in imaging protocols and analytical methods among studies [5, 25]. On the other hand, both tracts in the current study found to have increased fractional anisotropy values run from the prefrontal cortex, known to have long maturational time window. Thus, although the MRI was performed in VLGA and term children at same chronological age, the biological maturation profile might differ between these two cohorts, and this difference might be reflected in DTI metrics in this brain area. It has also been suggested that high fractional anisotropy values relate to increased myelination as a marker of compensatory recovery process after early white matter damage [28]. However, other factors in white matter such as axonal status and crossing fibres in voxel level could also affect these microstructural properties [26, 28, 32].

Previously, we demonstrated that VLGA children scored worse in inhibition/naming, inhibition/inhibition and inhibition/switching compared to term children at 9 years of age [3]. The current study showed that high fractional anisotropy values in the frontostriatal tracts, bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal caudate and bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal caudate were associated with poor performance in inhibition tasks. In contrast to our findings, previous studies have demonstrated correlations between low fractional anisotropy values in different white matter areas and poor executive functioning among very preterm populations [5, 31, 33, 34]. In addition, both negative and positive correlations between executive functions and fractional anisotropy in the different segments of the corpus callosum were found in 6-year-old preterm children [35]. Other studies have found no significant correlation between fractional anisotropy and executive functions [36, 37]. However, the tests measuring executive functioning in previous studies were dissimilar, and white matter areas evaluated in the present and previous studies differed from one another. The correlation variability between DTI metrics and neurocognitive functions could also stem from differences in vulnerability or the developmental stages of specific tracts [38]. Previously, VLGA individuals with higher fractional anisotropy in certain corticospinal and corpus callosal tracts had worse outcome in fine motor and executive functions, respectively, indicating — in line with our study — that higher fractional anisotropy values do not always imply better function [35, 39]. While projecting from the frontal lobe to the caudate nucleus, the frontostriatal tracts cross with callosal and association fibres [8]. Thus, it is possible that the correlation between increased fractional anisotropy values in dorsolateral prefrontal caudate and ventrolateral prefrontal caudate tracts and unfavourable executive functioning might be related to the effect of crossing fibres or might reflect axonal loss and disrupted branching in those white matter areas [26, 28, 32].

Among the strengths of the present study, we consider that our VLGA population belonged to the well-defined prospective cohort [3, 12]. In addition, the study included a comparison group of term children. All the children underwent imaging and neuropsychological assessments within the same age range. The same MRI scanner was used to obtain MRI sequences for all participants. DTI is known to be prone to artefacts, particularly from motion. In the current study, data quality control was carried out with DTIPrep [17]. Data were checked for slice-wise and interlace-wise intensity differences. Eddy current and motion defects were corrected, and data were checked gradient-wise for residual motion or deformations. Gradient directions that had image artefacts were removed from the data. The DTI analyses were performed using well-defined techniques [18, 19]. The evaluation of executive functioning was based on an objective and standardised method [16]. The size of our VLGA group corresponded with the size of previous DTI study groups [25, 27, 30]. To avoid Type I error, multiplicity of the analyses was controlled, and correction for multiple comparison was used. A potential concern for our study was the small group size of term children, which could have affected hypothesis testing and could have resulted in Type II error. However, the group of term children was age- and gender-matched, randomly recruited from the Oulu University Hospital birth register, and comprised a representative sample of 9-year-old schoolchildren with no severe neurologic impairment.

Conclusion

Very preterm children had higher fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity values in diffusion tensor imaging bilaterally in two frontostriatal tracts when compared to term children at a comparable 9 years of age. Furthermore, the diffusion values of frontostriatal tracts correlated negatively with neuropsychological measures of inhibition in the very preterm children. These results indicate that white matter microstructure is different in very preterm children — even with no severe neurologic impairment — when compared to term children and that this difference might reflect the complex maturational processes of specific neurodevelopmental abilities at school age.

References

Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C et al (2017) Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ 358:j3448

Brydges CR, Landes JK, Reid CL et al (2018) Cognitive outcomes in children and adolescents born very preterm: a meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 60:452–468

Kallankari H, Kaukola T, Olsen P et al (2015) Very preterm birth and foetal growth restriction are associated with specific cognitive deficits in children attending mainstream school. Acta Paediatr 104:84–90

Caldinelli C, Froudist-Walsh S, Karolis V et al (2017) White matter alterations to cingulum and fornix following very preterm birth and their relationship with cognitive functions. Neuroimage 150:373–382

Vollmer B, Lundequist A, Martensson G et al (2017) Correlation between white matter microstructure and executive functions suggests early developmental influence on long fibre tracts in preterm born adolescents. PLoS One 12:e0178893

Costa DS, Miranda DM, Burnett AC et al (2017) Executive function and academic outcomes in children who were extremely preterm. Pediatrics 140:e20170257

Niendam TA, Laird AR, Ray KL et al (2012) Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 12:241–268

Shang CY, Wu YH, Gau SS et al (2013) Disturbed microstructural integrity of the frontostriatal fiber pathways and executive dysfunction in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Med 43:1093–1107

Kersbergen KJ, Leemans A, Groenendaal F et al (2014) Microstructural brain development between 30 and 40 weeks corrected age in a longitudinal cohort of extremely preterm infants. Neuroimage 103:214–224

Vorona GA, Berman JI (2015) Review of diffusion tensor imaging and its application in children. Pediatr Radiol 45:S375–S381

Counsell SJ, Edwards AD, Chew AT et al (2008) Specific relations between neurodevelopmental abilities and white matter microstructure in children born preterm. Brain 131:3201–3208

Saunavaara V, Kallankari H, Parkkola R et al (2017) Very preterm children with fetal growth restriction demonstrated altered white matter maturation at nine years of age. Acta Paediatr 106:1600–1607

Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R et al (1978) Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr 92:529–534

de Vries LS, Eken P, Dubowitz LM (1992) The spectrum of leukomalacia using cranial ultrasound. Behav Brain Res 49:1–6

Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (2000) Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev Med Child Neurol 42:816–824

Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp SL (2007) NEPSY II, 2nd edn. PsychCorp/Pearson Clinical Assessment, San Antonio

Liu Z, Wang Y, Gerig G et al (2010) Quality control of diffusion weighted images. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.844748

Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE et al (2012) FSL. Neuroimage 62:782–790

Walter B, Blecker C, Kirsch P et al (2003) MARINA: an easy to use tool for the creation of masks for region of interest analyses. 9th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain, June 19–22, New York. Neuroimage 19

Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ (2012) Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 141:2–18

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289–300

Fiske A, Holmboe K (2019) Neural substrates of early executive function development. Dev Rev 52:42–62

Réveillon M, Hüppi PS, Barisnikov K (2018) Inhibition difficulties in preterm children: developmental delay or persistent deficit? Child Neuropsychol 24:734–762

Beaulieu C (2002) The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system — a technical review. NMR Biomed 15:435–455

Li K, Sun Z, Han Y et al (2015) Fractional anisotropy alterations in individuals born preterm: a diffusion tensor imaging meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 57:328–338

Travis KE, Adams JN, Ben-Shachar M et al (2015) Decreased and increased anisotropy along major cerebral white matter tracts in preterm children and adolescents. PLoS One 10:e0142860

Jurcoane A, Daamen M, Scheef L et al (2016) White matter alterations of the corticospinal tract in adults born very preterm and/or with very low birth weight. Hum Brain Mapp 37:289–299

Dodson CK, Travis KE, Ben-Shachar M et al (2017) White matter microstructure of 6-year-old children born preterm and full term. Neuroimage Clin 16:268–275

Rimol LM, Botellero VL, Bjuland KJ et al (2018) Reduced white matter fractional anisotropy mediates cortical thickening in adults born preterm with very low birth weight. Neuroimage 188:217–227

Solsnes AE, Sripada K, Yendiki A et al (2016) Limited microstructural and connectivity deficits despite subcortical volume reductions in school-aged children born preterm with very low birth weight. Neuroimage 130:24–34

Murray AL, Thompson DK, Pascoe L et al (2016) White matter abnormalities and impaired attention abilities in children born very preterm. Neuroimage 124:75–84

Jeurissen B, Leemans A, Tournier JD et al (2013) Investigating the prevalence of complex fiber configurations in white matter tissue with diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 34:2747–2766

Skranes J, Lohaugen GC, Martinussen M et al (2009) White matter abnormalities and executive function in children with very low birth weight. Neuroreport 20:263–266

Loe IM, Adams JN, Feldman HM (2019) Executive function in relation to white matter in preterm and full term children. Front Pediatr 6:418

Dubner SE, Dodson CK, Marchman VA et al (2019) White matter microstructure and cognitive outcomes in relation to neonatal inflammation in 6-year-old children born preterm. Neuroimage Clin 23:101832

Duerden EG, Card D, Lax ID et al (2013) Alterations in frontostriatal pathways in children born very preterm. Dev Med Child Neurol 55:952–958

Thompson DK, Lee KJ, Egan GF et al (2014) Regional white matter microstructure in very preterm infants: predictors and 7 year outcomes. Cortex 52:60–74

Fischi-Gomez E, Vasung L, Meskaldji DE et al (2015) Structural brain connectivity in school-age preterm infants provides evidence for impaired networks relevant for higher order cognitive skills and social cognition. Cereb Cortex 25:2793–2805

Hollund IMH, Olsen A, Skranes J et al (2017) White matter alterations and their associations with motor function in young adults born preterm with very low birth weight. Neuroimage Clin 17:241–250

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Oulu including Oulu University Hospital. Hanna Kallankari and Virva Saunavaara contributed equally to this study. This study was funded by the Alma och K.A. Snellman Foundation (H.K., T.K.) and Foundation for Paediatric Research, Finland (T.K.). We thank Päivi Olsen, MD, PhD, for contributing to the study design. We also thank Noora Korkalainen, MD, who participated in recruiting the study participants and performed the structured neurologic assessment for some of the children. We are grateful to the children and the parents who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kallankari, H., Saunavaara, V., Parkkola, R. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in frontostriatal tracts is associated with executive functioning in very preterm children at 9 years of age. Pediatr Radiol 51, 112–118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04802-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04802-1