Abstract

Parents of children in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) are often unprepared for family meetings (FM). Clinicians often do not follow best practices for communicating with families, adding to distress. An interprofessional team intervention for FM is feasible, acceptable, and positively impacts family preparation and conduct of FM in the CICU. We implemented a family- and team-support intervention for conducting FM and conducted a pretest–posttest study with parents of patients selected for a FM and clinicians. We measured feasibility, fidelity to intervention protocol, and parent acceptability via questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. Clinician behavior in meetings was assessed through semantic content analyses of meeting transcripts tracking elicitation of parental concerns, questions asked of parents, and responses to parental empathic opportunities. Logistic and ordinal logistic regression assessed intervention impact on clinician communication behaviors in meetings comparing pre- and post-intervention data. Sixty parents (95% of approached) were enrolled, with collection of 97% FM and 98% questionnaire data. We accomplished > 85% fidelity to intervention protocol. Most parents (80%) said the preparation worksheet had the right amount of information and felt positive about families receiving this worksheet. Clinicians were more likely to elicit parental concerns (adjusted odds ratio = 3.42; 95%CI [1.13, 11.0]) in post-intervention FM. There were no significant differences in remaining measures. Implementing an interprofessional team intervention to improve family preparation and conduct of FM is locally feasible, acceptable, and changes clinician behaviors. Future research should assess broader impact of training on clinicians, patients, and families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents of patients in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) experience severe distress during their child’s hospitalization [1, 2], often made worse by suboptimal communication with their child’s clinicians [3,4,5]. Parental understanding of their child’s heart disease is often rated lower by their clinicians than parental self-perception [6] and parents of children who die have a delayed appreciation of their child’s prognosis [7, 8]. When parents receive conflicting information from team members, this can also diminish the quality of communication and negatively impact parental decision making [9]. Research on how to optimize communication with families has been prioritized by several groups of experts [10, 11] and professional organizations recommend family meetings (FM) for better coordination of communication with families [11, 12]. FM are when families meet with a subset of their child’s clinicians to receive both information on their child’s condition [13] and emotional support from clinicians [14, 15], and provide an opportunity for involvement in the decision making process [14,15,16,17].

Despite recommendations for how to conduct meetings [18], most evaluations of FM demonstrate significant missed opportunities. Opportunities to elicit parental concerns and questions are often missed, despite research that demonstrates higher parental satisfaction when they participate in more meaningful ways [19]. Parents request support in how to communicate with their child’s clinicians and report apprehension when told the team recommends a family meeting, however, there are no evidence-based approaches for how to support parental preparation for a family meeting [20].

To optimize the preparation of interprofessional teams and parents for FM, we utilized an experience-based codesign with pediatric CICU clinicians and families to develop the intervention “CICU Teams and Loved ones Communicating” (CICU TALC) [21]. CICU TALC sought to increase clinicians’ skills when communicating with families and colleagues, institute processes that prioritized parental concerns and questions, clarify clinicians’ roles in the family meeting, and to help families know what to expect from the family meeting. The objective of this Medical Research Council Phase II pilot study [22] was to evaluate the feasibility of enrolling families and collecting family data, fidelity to the intervention protocol after training clinicians in CICU TALC, parents’ perception of acceptability of the intervention, and to determine if there was any impact on clinician communication behaviors of engaging parental involvement in FM.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This pre- and post-test pilot intervention study was conducted at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), a large urban pediatric hospital with 32 dedicated cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) beds. Pre-intervention data was collected from December 2018 to March 2020 and post-intervention data was collected from July 2021 to September 2022. For context, in the CHOP CICU, it is typical practice for rounds to occur outside the patient’s room or at their bedspace in open bays with family caregivers invited to participate if they would like. There is no other typical interval of a planned FM independent of ones initiated by the clinical team due to a clinical change or when requested by the family. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board approved this study, and the study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03749330).

Population

Three populations participated in this study: CICU patients, parents of patients, and CICU clinicians who participated in a family meeting for an enrolled patient. Inclusion criteria for patients were that they are < 18 years old, had been admitted to the CICU for at least 14 days, and were selected for a family meeting discussion. The rationale for the CICU length of stay criterion was that patients who had been admitted to the CICU for 14 days or longer were perceived by the CICU clinicians as having an extended stay, which warranted review and discussion with families. Parents were eligible if their child was chosen for a family meeting, they were a legal decision maker, ≥ 18 years old, and were English-speaking. While permission was obtained from any parent who participated in a family meeting because it was recorded, only 1 parent per child was consented and enrolled to complete a post-intervention survey. CICU Clinicians were included based on participation in a family meeting with an enrolled patient.

Intervention

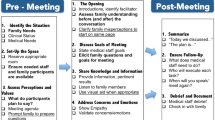

An experience-based codesign was used with CICU clinicians and parents of children hospitalized in the CICU to develop the CICU Teams and Loved Ones Communicating (CICU TALC) intervention, including both clinician and parent facing elements and was described in detail elsewhere [21]. The intervention included both the development of processes to improve how teams and families prepared for and conducted family meetings and the implementation of communication skills training for interprofessional team members (Fig. 1). Communication skills training for clinicians focused on communicating serious news to families using a Vital Talk type training [23] and interprofessional communication skills training to optimize teamwork in communication within the team and the family. New team processes to better support the preparation for and conduct of FM by interprofessional teams included assigning a nurse to facilitate a pre-family meeting huddle to discuss the goals of the FM and incorporate all clinicians’ perspectives in developing a care plan and how to optimally communicate it to families. Four roles were assigned to clinicians for the FM to improve role clarity. These roles included a facilitator, information provider, emotional support coordinator, and someone to document the discussion. Finally, clinicians were trained in how to debrief the family meeting within a 5 min time frame to reinforce skills and promote future collaboration with team members.

The parent-facing components of CICU TALC included a handout provided in advance of the meeting to help parents prepare for their family meeting. The preparation worksheet aimed to inform them about what a family meeting is; the reason for their family meeting (described by one or more of five general categories: update on a prolonged hospitalization, new information, addressing conflicting information identified by the family, discharge planning, or decision about a medical treatment plan); and the likely questions that would be discussed in the meeting (e.g., what do you already understand about your child’s condition; what does it mean to be a good parent to your child). The worksheet also encouraged parents to write down their concerns about their child’s care, questions, communication preferences, and their preferences of which clinicians should attend the meeting. The social worker collected these questions and preferences from the family prior to the family meeting to share with the rest of the team in preparation for the meeting. After the family meeting, families received a summary sheet filled out by a clinician during the meeting. The summary sheet recorded all attendants’ names and roles, agenda items with corresponding action items, and items to be discussed later with other team members.

Data Collection

The research team tracked participant eligibility, enrollment, data collection, completion rates, and fidelity to intervention protocol. Parental questionnaires collecting information about acceptability of CICU TALC were administered via REDCap after family meeting participation. Each family meeting was audio recorded and transcribed. A subset of parents was randomly selected for participation in a semi-structured post-intervention acceptability interview which was conducted in person or over the phone, audio recorded, and transcribed.

Outcomes

Primary trial outcomes were feasibility of enrolling families, fidelity to the protocol, and parental perception of acceptability of CICU TALC. The secondary outcome was the impact of CICU TALC on clinician communication behaviors in FM comparing pre- and post-intervention FM.

Feasibility

Feasibility outcomes were measured by intervention enrollment numbers, retention, and family meeting data collection. Retention was assessed by examining the proportion of dyads who completed all data elements. Data collection was the amount of family meeting data collected compared to the intended data elements.

Fidelity to Intervention Protocol

The research team assessed fidelity of enactment to intervention protocol [24, 25] at post-intervention by evaluating meeting transcripts/recordings. Fidelity criteria that were defined prior to the data collection were (a) providing parents with the Preparation Worksheet before the family meeting, (b) following up with families about their communication preferences and questions for the team prior to the family meeting, and (c) provision of a Family Meeting Summary Sheet to the family after the family meeting.

Acceptability

Parents’ perceptions of the acceptability of the CICU TALC parent-facing materials were assessed using an adapted version of a previously validated acceptability satisfaction questionnaire [26] and semi-structured interviews. Open-ended interview questions were designed and piloted to solicit perspectives about the acceptability and utility of CICU TALC materials and the need for additional adaptation or improvement.

Clinician Behaviors

We assessed clinician behaviors in the FM using a modified VitalTalk coding scheme named The Studying Communication in Oncologist-Patient Encounters (SCOPE) [27,28,29]. Behaviors evaluated included elicitation of parental concerns, questions asked of the parents, and responses to empathic opportunities by parents when they expressed a negative emotion. We also tracked proportion of words spoken by professional group to determine if there was a shift in who contributed verbally to the family meeting.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize feasibility, fidelity, and parental questionnaire responses for acceptability. We followed COREQ guidelines [30] for qualitative data. An integrated approach [31] was used to analyze the parent interview data for acceptability, with a priori intervention-related codes as well as grounded theory codes that emerged from the interview transcripts. Study team members iteratively developed the code book by independently reviewing and comparing 16 successive transcripts. Once a common understanding of the codebook was established, 2 research coordinators coded the remaining interviews and resolved any coding disagreements through comparison and discussion.

A mixed methods approach was used to analyze the clinician behaviors in the FM. First, the FM were coded using the SCOPE codebook by trained study team members with double coding performed on at least 20% of transcripts. Discrepancies were resolved through comparison and discussion. We then evaluated the data for a quantitative count of the number of instances of each of the relevant outcome behaviors. Clinician behaviors on a meeting level were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s Chi-squared test for categorical/dichotomous variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Pre and post-parent data was independent with different cohorts of participants and thus we could not perform statistical analysis to account for paired parental data. Outcomes that reached the prespecified threshold of significance (P value < 0.05) were then evaluated with logistic and ordinal logistic regression to assess CICU TALC impact on clinician communication behaviors at the meeting level comparing pre- and post-intervention data and controlling for number of participants in the meeting since the more people in the meeting, the less percentage talking time any one individual is likely to have.

Qualitative analyses for both the parent acceptability interviews and the clinician behavior in FM were performed in NVivo 13 [32]. Quantitative analysis was performed using the R (4.2.2) statistical software [33].

Results

Population

Patients and Parents

A total of 60 patients, each with a parent (for a total of 60 parents) participated in CICU TALC, of which 30 were in the pre-intervention and 30 in post. Demographics of the parents who consented to further data collection was 68% mothers, 58% White, and 77% were non-Hispanic (Table 1, top). Eighty percent of patients were less than 6 months old, 60% White, and 30% had a syndromic diagnosis (Table 1, bottom). The family meeting was conducted on CICU day of admission 35 (SD 29.8) in the pre-intervention and day 40 (SD 40.7) of the post-intervention. Additional parent and patient characteristics are in Supplemental Table A.

Families Present in Family Meetings

Even though only one parent per patient was officially enrolled in the study, more family members were allowed to participate in the FM. In a total of 58 FM, 72% had 2 parents present and on average 1.9 (median 2; range 1–4) family members (including parents, grandparents, siblings, and other support people). There was no difference in parent presence when comparing pre- and post-intervention FM.

Clinicians Present in Family Meetings

On average (mean) there were 4 clinicians in the pre-intervention (median 3.5; range 1–7) and post-intervention (median 3; range 2–6) meetings. In the pre-intervention, 96% of all meetings had a nurse present, in the post-intervention only 73% (due to COVID-19 pandemic staffing challenges). Social workers were present in 93% of all meeting (pre and post). The chaplain only participated twice in pre-intervention FM and once in a post-intervention family meeting. Out of 72 clinicians that participated in FM, 17 Clinicians (23.6%) were in both pre- and post-intervention FM (9 attendings, 4 social workers, and 5 nurses). 13 (18.1%) clinicians (7 attendings, 4 social workers, and 2 nurses) were trained in CICU TALC and participated in both pre- and post-intervention FM. 76% of all family meetings were led by one of the 7 trained attendings (82% in pre- and 70% in post-intervention). The 4 social workers that were trained participated in 91% of all FM (93% in pre- and 90% in post-intervention). Overall, at least one clinician (physician, social worker, or nurse) who completed the full intervention was present in each FM. All attendings who led the family meeting, even if they had not completed the training, were briefed in the elements of the intervention relevant to the family meeting prior to participation. Further information on clinician demographics is in Supplemental Table B.

Feasibility

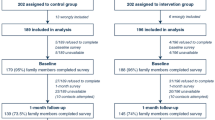

A total of 63 patient-parent pairs were approached in the pre- and post-intervention (Fig. 2). We enrolled and collected questionnaire data from 100% of parents (n = 30) who were approached in the pre-intervention phase and from 93% (28/30) of the pre-intervention FM. We enrolled 91% (n = 30) of the 33 approached parents for the post-intervention FM. The three families that declined consent described feeling overwhelmed and wanted to focus on their child’s medical needs. Of these post-intervention parents, 97% (29) completed the questionnaire and we were able to collect 100% of family meeting data. In total, we were able to collect 98% of parent questionnaire data and 97% of family meeting data. On average the duration of FM in the pre-intervention phase was 49 min (SD 21) and 51 min (SD 19) in post-intervention.

Fidelity of Intervention to Protocol

Intervention fidelity was monitored according to recommended practice [24, 25]. After evaluating the adherence to the intervention protocol for 8 successive post-intervention team and FM, the research team decided to provide augmented intervention delivery support to increase fidelity (see supplemental document C) with a study team member providing intervention element supports. Subsequently, enactment increased for all intervention measures (e.g., use of the summary sheet) above the pre-specified fidelity threshold of 90% after the delivery support was implemented (Table 2).

Parent Perception of Intervention Acceptability

Demographic characteristics for parents who participated in interviews are in Supplemental Table D.

Preparation Worksheet

Post-intervention ratings of intervention acceptability were strong (Table 3). Most parents thought the length of the preparation worksheet was about right (88%) and had the right amount of information (80%). Most felt generally positive about parents receiving the preparation worksheet (80%). From the post-intervention interviews, qualitative themes and representative parent quotations are shown in Table 4. Themes surrounding the preparation worksheet included reduction of anxiety and help preparing and organizing thoughts. The only improvement parents suggested was that they would have liked to receive the preparation worksheet sooner to make better use of it.

Summary Sheet

Ninety six percentage of parents found the summary sheet helpful and were able to understand the summarized content. All parents said the summary sheet included the most important information discussed in the meeting (Table 3). In the acceptability interviews parents also expressed the pertinence and helpfulness of the summary sheet (Table 4). Some parents expressed that they would like the summary sheet to be more detailed, so they could use it as a clear reference point to evaluate their child’s progress.

Overall Family Meeting Experience

Overall, when parents first heard about the family meeting, they felt anxious but appreciated having a platform to voice their concerns (Table 4). After the meeting, parents felt re-assured that they had an opportunity to have their concerns heard and addressed.

Clinician Behavior

Demographic characteristics for clinicians who participated in FM is described in Supplemental Table B. Bivariate results of clinician behaviors are demonstrated in Table 5. After adjusting for number of participants, clinicians were more likely to elicit parental concerns (OR = 3.42; 95%CI [1.13, 11.0]) in post-intervention FM compared to pre-intervention. There were no significant differences in the number of questions asked of parents or percent of words spoken by different professionals although social workers may have spoken more in post-intervention meetings (OR = 2.59 [95% CI 0.91, 7.73]) (Table 6).

Discussion

Given the stress parents experience and the negative impact of communication breakdowns for families of children in the CICU, optimizing opportunities for interprofessional team communication with families is an important undertaking. These conversations can take a step back from the day-to-day management conversations to discuss the overall trajectory of care for the patient and clarify any misunderstandings that have occurred. Despite the potential benefits of family meetings, parents have anxiety about having a family meeting and can become overwhelmed in the meeting, reducing the ability to pose questions and absorb information [34]. Additionally, previous research has not demonstrated that family meetings impact parental perceptions of satisfaction with communication with the CICU team [35]. We hypothesized that families would benefit by having an opportunity to prepare for the meeting and by the team being aware of families’ questions in advance of the meeting. This CICU TALC intervention was designed with the goal of enhancing parental understanding, satisfaction with communication with the clinical team, and reducing parental anxiety [21].

This study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of implementing a complex team-based intervention for family meetings without extending their duration. Further, while not powered to assess efficacy, CICU TALC did correlate with greater elicitation of parental concerns, which is essential to ensuring family-centered care [34]. We were also able to collect relevant data from FM and parents and learned important lessons about how to ensure fidelity to the intervention protocol, all of which is central for future efficacy trials of CICU TALC.

Three aspects of the findings warrant discussion. First, our study demonstrated feasibility of implementing interprofessional team training with practicing clinicians even in high acuity settings at a single institution, which is consistent with other analyses of team trainings in the healthcare setting [36]. With high rates of parental enrollment, retention, and data collection we have demonstrated feasibility essential to drive future study of CICU TALC. Additionally, the implementation of complex behavioral interventions require careful monitoring of enactment (i.e., that the clinicians who were trained in CICU TALC performed the elements of the intervention) to ensure that the central elements of the protocol are implemented to be able to assess efficacy in future trials. [24] The need for an intervention delivery support to increase fidelity serves as a potential constraint for future implementation but may also demonstrate that future studies could be randomized at the patient level since teams will be unlikely to implement the intervention elements without ongoing support. Other studies providing support to adult surrogates of ICU patients have depended on the use of a person dedicated to ensuring study procedures are completed, similar to this pilot [37].

Second, we found substantial support and high rates of acceptability in both our quantitative and qualitative assessment of parental perception of CICU TALC. The intervention had been grounded in previous research which demonstrated that parents want to be included as valued members of their child’s care team and when that happens they are more likely to feel a sense of control, even in the face of prognostic uncertainty [20]. Additionally, CICU TALC aimed to provide guidance for parents on how to partner with their child’s providers and offered tangible supports to do so, an identified need of parents of children with congenital heart disease [38]. Even for parents who felt they were successful in understanding their child’s condition and advocating for them, the materials provided a useful double check in ensuring they were not missing anything and were doing all that they could. For families who were struggling to communicate effectively with teams, the materials provided an essential point of reflection to collect their thoughts and prepare for meetings and then with the summary sheet they could integrate what they learned to support future conversations.

Third, regarding potential efficacy of the intervention, while noting the small sample size of our pilot study we did find one statistically significant change in clinician behavior and several trends in the direction we would expect given CICU TALC’s goals. Clinicians significantly increased elicitation of parental concerns which was recommended as an important component of family-centered care in the ICU [12] and has been demonstrated to increase surrogate involvement in medical decision making [39]. There were also trends of more questions asked of parents to engage them further and more empathic responses to negative emotions expressed by families. Other research has demonstrated the limited number of empathic statements offered by clinicians in response to parents expressing their negative emotions [40] which hinders clinician ability to provide explicit support for families in times of high stress. The goal of increasing non-physician contributions in FM, which may also positively impact expressions of empathy and family engagement, was shown with a trend in social worker contributions in the meeting. This comes in contrast to data from multiple pediatric ICU settings where physicians dominated almost all of clinician communication [41, 42].

This pilot study had several limitations that bear discussion. First, CICU TALC was only implemented in one institution with a robust commitment to FM and adequate staffing to afford attendance by an interprofessional team. Second, the parent-facing materials were only available in English and the families who participated in the co-design were all English-speaking and did not consist of a representative population in the United States. Third, the pre- versus post-intervention study design was not able to account for all the changes in clinician and family experiences due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which encompassed none of the pre-intervention data collection and all the post-intervention data collection. In sum, future research should be done in other institutions with easily scalable elements like preparatory worksheets and summary sheets available in even poorer resourced hospitals; CICU TALC should be translated and culturally adapted for populations of families who may be at the highest risk for poor communication; and studies should employ a more rigorous study design to control for external events that have a broad impact on clinicians and families.

Conclusion

An interprofessional team intervention in the pediatric CICU is feasible to implement and can be done so with high fidelity in a well-resourced setting. This intervention is also acceptable to English-speaking families, regardless of whether they perceive they are struggling to communicate effectively with their child’s healthcare team. Finally, CICU TALC may positively impact clinician behaviors in FM. These results warrant future efficacy testing of CICU TALC for impacts on parental understanding, satisfaction with communication, and stress.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Kasparian NA, Kan JM, Sood E, Wray J, Pincus HA, Newburger JW (2019) Mental health care for parents of babies with congenital heart disease during intensive care unit admission: systematic review and statement of best practice. Early Hum Dev 139:104837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104837

Woolf-King SE, Anger A, Arnold EA, Weiss SJ, Teitel D (2017) Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004862

Diaz-Caneja A, Gledhill J, Weaver T, Nadel S, Garralda E (2005) A child’s admission to hospital: a qualitative study examining the experiences of parents. Intensive Care Med 31:1248–1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2728-8

Sood E, Karpyn A, Demianczyk AC, Ryan J, Delaplane EA, Neely T, Frazier AH, Kazak AE (2018) Mothers and fathers experience stress of congenital heart disease differently: recommendations for pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 19:626–634. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001528

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larche J, Liotier J, Papazian C, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B, Group FS (2005) Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of itensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171:987–994. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC

Morell E, Miller MK, Lu M, Friedman KG, Breitbart RE, Reichman JR, McDermott J, Sleeper LA, Blume ED (2021) Parent and physician understanding of prognosis in hospitalized children with advanced heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 10:e018488. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.120.018488

Balkin EM, Wolfe J, Ziniel SI, Lang P, Thiagarajan R, Dillis S, Fynn-Thompson F, Blume ED (2015) Physician and parent perceptions of prognosis and end-of-life experience in children with advanced heart disease. J Palliat Med 18:318–323. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0305

Blume ED, Balkin EM, Aiyagari R, Ziniel S, Beke DM, Thiagarajan R, Taylor L, Kulik T, Pituch K, Wolfe J (2014) Parental perspectives on suffering and quality of life at end-of-life in children with advanced heart disease: an exploratory study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 15:336–342. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000072

Miller MK, Blume ED, Samsel C, Elia E, Brown DW, Morell E (2022) Parent-provider communication in hospitalized children with advanced heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-02913-0

Cousino MK, Lord BT, Blume ED (2021) State of the science and future research directions in palliative and end-of-life care in paediatric cardiology: a report from the Harvard Radcliffe Accelerator Workshop. Cardiol Young. https://doi.org/10.1017/s104795112100233x

Blume ED, Kirsch R, Cousino MK, Walter JK, Steiner JM, Miller TA, Machado D, Peyton C, Bacha E, Morell E (2023) Palliative care across the life span for children with heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000114

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME (2017) Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 45:103–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169

Arya B, Levasseur JS, Williams SM, Ismeé A (2013) Parents of children with congenital heart disease prefer more information than cardiologists provide. Congenit Heart Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00706.x

Fisk AC, Mott S, Meyer S, Connor JA (2022) Parent perception of their role in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 41:2–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000503

Simeone S, Pucciarelli G, Perrone M, Angelo GD, Teresa R, Guillari A, Gargiulo G, Comentale G, Palma G (2018) The lived experiences of the parents of children admitted to a paediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Heart Lung 47:631–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.08.002

Wyatt KD, List B, Brinkman WB, Prutsky Lopez G, Asi N, Erwin P, Wang Z, Domecq Garces JP, Montori VM, LeBlanc A (2015) Shared decision making in pediatrics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Pediatr 15:573–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.03.011

Blume E, Morell Balkin E, Aiyagari R, Ziniel SI, Beke D, Thiagarajan R, Taylor L, Kulik T, Pituch KJ, Wolfe J (2014) Parental perspectives on suffering and quality of life at end-of-life in children with advanced heart disease: an exploratory study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 15:336–342. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000072

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Rubenfeld GD (2001) The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med 29:N26-33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200102001-00006

October TW, Hinds PS, Wang J, Dizon ZB, Cheng YI, Roter DL (2016) Parent satisfaction with communication is associated with physician’s patient-centered communication patterns during family conferences. Pediatr Crit Care Med 17:490–497. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000719

Gramszlo C, Girgis H, Hill D, Walter JK (2023) Parent communication with care teams and preparation for family meetings in the paediatric cardiac ICU: a qualitative study. Cardiol Young. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951123001282

Walter JK, Hill D, Drust WA, Lisanti A, DeWitt A, Seelhorst A, Hasiuk ML, Arnold R, Feudtner C (2022) Intervention codesign in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit to improve family meetings. J Pain Symptom Manage 64:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.03.010

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, Tyrer P (2000) Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 321:694–696. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694

Vital Talk VitalTalk.org. VitalTalk

Resnick B, Inguito P, Orwig D, Yahiro JY, Hawkes W, Werner M, Zimmerman S, Magaziner J (2005) Treatment fidelity in behavior change research: a case example. Nurs Res 54:139–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200503000-00010

Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, Czajkowski S (2004) Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychol 23:443–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443

Barry M, Fowler F, Mulley A, Henderson J, Wennberg J (1995) Patient reactions to a program designed to facilitate patient participation in treatment decision for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Care 33:771–782. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199508000-00003

Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, Barley GE, Gooley TA, Tulsky JA (2007) Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 167:453. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.5.453

Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, Edlund B, Christianson P, Arnold RW, O’Connor K, Kross EK, Reinke LF, Cecere Feemster L, Fryer-Edwards K, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, Curtis JR (2014) Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med 17:159–166. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0318

Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Jeffreys AS, Rodriguez KL, Skinner CS, Farrell D, Abernethy AP, Pollak KI (2011) Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 155:593. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00007

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ (2007) Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 42:1758–1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

Lumivero (2020) Nvivo 13

Team RC (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Gramszlo C, Girgis H, Hill D, Walter JK (2024) Parent communication with care teams and preparation for family meetings in the paediatric cardiac ICU: a qualitative study. Cardiol Young 34:113–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951123001282

Walter JK, Feudtner C, Cetin A, DeWitt AG, Zhou M, Montoya-Williams D, Olsen R, Griffis H, Williams C, Costarino A (2023) Parental communication satisfaction with the clinical team in the paediatric cardiac ICU. Cardiol Young. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951123001555

Hughes AM, Gregory ME, Joseph DL, Sonesh SC, Marlow SL, Lacerenza CN, Benishek LE, King HB, Salas E (2016) Saving lives: a meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. J Appl Psychol 101:1266–1304. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000120

Seaman JB, Arnold RM, Buddadhumaruk P, Shields AM, Gustafson RM, Felman K, Newdick W, SanPedro R, Mackenzie S, Morse JQ, Chang CH, Happ MB, Song MK, Kahn JM, Reynolds CF 3rd, Angus DC, Landefeld S, White DB (2018) Protocol and fidelity monitoring plan for four supports. a multicenter trial of an intervention to support surrogate decision makers in intensive care units. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15:1083–1091. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-157SD

Gramszlo C, Karpyn A, Demianczyk AC, Shillingford A, Riegel E, Kazak AE, Sood E (2020) Parent perspectives on family-based psychosocial interventions for congenital heart disease. J Pediatr 216:51-57.e52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.09.059

Street RL Jr, Voigt B (1997) Patient participation in deciding breast cancer treatment and subsequent quality of life. Med Decis Making 17:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x9701700306

Walter JK, Sachs E, Schall TE, Dewitt AG, Miller VA, Arnold RM, Feudtner C (2019) Interprofessional teamwork during family meetings in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.002

Walter JK, Sachs E, Schall TE, Dewitt AG, Miller VA, Arnold RM, Feudtner C (2019) Interprofessional teamwork during family meetings in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage 57:1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.002

October TW, Dizon ZB, Roter DL (2018) Is it my turn to speak? An analysis of the dialogue in the family-physician intensive care unit conference. Patient Educ Couns 101:647–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.020

Acknowledgements

Dr. Walter was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL141700.

Funding

Funding was provided by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Grant No. K23HL141700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JW, AD, WQ, HG, JS, MC, RA and CF conceptualized the study and analysis; HG, JS, and WQ conducted the quantitative analysis; JW and AC wrote the main manuscript text and DH and AC prepared the tables and figures; KK and AC conducted the qualitative analysis and drafted the methods; AD, RA, CF, MC, JT and KP provided critical feedback on the draft and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walter, J., Hill, D.L., Cetin, A. et al. A Pediatric Interprofessional Cardiac Intensive Care Unit Intervention: CICU Teams and Loved Ones Communicating (CICU TALC) is Feasible, Acceptable, and Improves Clinician Communication Behaviors in Family Meetings. Pediatr Cardiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-024-03497-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-024-03497-7