Abstract

Pediatricians must be able to diagnose, triage, and manage infants and children with congenital heart disease. The pediatric cardiology division at the Medical University of South Carolina updated their curriculum for pediatric residents to a format supported by constructivist learning theory. The purpose of this study is to determine if shorter, interactive learning with fellow and faculty involvement improved pediatric cardiology knowledge demonstrated through test scores and resident satisfaction. A curriculum of short lectures and interactive workshops was delivered over 6 weeks in August and September 2018. Residents answered a 10-question pretest prior to the curriculum, followed by a post-test immediately after the last session and a delayed post-test 8 months later. Residents also provided summative feedback on the educational sessions. Sixty-six residents were eligible to participate in the curriculum with 44 (67%) completing the pretest, 40 (61%) completing the post-test, and 33 (50%) completing the delayed post-test. The mean score increased significantly from 56 to 68% between the pretest and post-test (p = 0.0018). The delayed post-test mean score remained high at 71% without significant change (p = 0.46). Overall feedback was positive highlighting the interactive nature of lectures and the participation of cardiology fellows. Using an interactive, multimodal educational series, pediatric residents had a significant increase in pediatric cardiology test scores and demonstrated good retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the transition of management of infants and children with congenital heart disease (CHD) from neonatal and pediatric intensive care units to cardiac intensive care units, many general pediatrics residents have decreased exposure to this patient population [1]. Nevertheless, general pediatricians must be able to diagnose, manage, and triage these often critically ill patients. Additionally, 4% of the questions on the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) General Pediatrics certification exam are related to cardiology [2]. Unfortunately, one pediatric residency program reported only 38% confidence with a fundamental topic like critical CHD screening [3]. Pediatric cardiologists and pediatric residency program directors need to ensure that all general pediatric residents receive adequate training in this area.

The pediatric residency at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) recently changed their didactic schedule from daily noon conferences to once weekly academic half days. The pediatric cardiology division used this opportunity to update their curriculum to a format supported by the constructivist learning theory, which is based on principles from Kant and Piaget through which active learning encourages assimilation and accommodation of new knowledge into existing schema. The purpose of this study is to determine if shorter lectures with more active learning with faculty and fellow participation is associated with comprehension and retention of core pediatric cardiology knowledge as demonstrated by mean test scores.

Methods

Study Population

The MUSC pediatric residency has about 66 residents at any time, comprised of 14 categorical, 4 internal medicine-pediatrics, 2 primary-care track, and 1 child neurology residents per year. All residents at the program in the 2018–2019 academic year attended the curriculum, clinical duties permitting. The residency program’s formal education series repeats on a 1.5-year cycle, so that most general pediatrics residents should experience each subspecialty curriculum twice during their residency. A MUSC institutional certification tool determined this project to be quality improvement and therefore not subject to IRB review or approval.

Curriculum Development

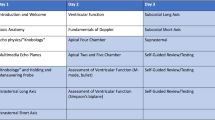

Nine hours of education was delivered over a period of 6 weeks in August to September of 2018. The objectives of the curriculum were to teach the ABP General Pediatrics certification exam content specifications and to prepare residents for practice in general pediatrics. Content was divided into seven lecture topics, which were presented by pediatric cardiology faculty and fellows (Table 1). All lectures were limited to 30 min, except for cyanotic and acyanotic CHD, which were 60 min each to facilitate the breadth of content. Teachers were encouraged to include an interactive component in their lecture. Additional active learning sessions included: a discussion of Medical Emergency Team or code events on the cardiology step-down unit, a murmur lab with audio examples and case studies, a cardiac mock code simulation, an electrocardiogram (ECG) reading lab, small group case studies, and a Jeopardy!-style review session. Most of the lectures were presented by pediatric cardiology faculty with subspecialty training in the respective topic and the majority of the active learning sessions were led by current pediatric cardiology fellows in all levels of training (post graduate year 5–7).

Knowledge Evaluation/Analysis

Prior to curriculum implementation, residents answered a pretest comprised of 10 open-ended questions followed by the same set of questions delivered immediately after the last session (post-test) and approximately 8 months after the last lecture (delayed post-test). The aim for each question was to emphasize a learning point from different sessions in line with content specifications for the ABP General Pediatrics certifying exam. Questions were designed to be open-ended, which require a higher level of cognitive processing, as opposed to multiple choice questions, which can often be a test of recognition or recall. Due to time constraints, the test was constructed to take around 5 min to complete. Scores were evaluated with F-test for variance and two-tailed t-tests. Open-ended verbal and written feedback was solicited by both chief residents and curriculum developers.

Results

Sixty-six residents were eligible to participate in the curriculum with 44 (67%) completing the pretest, 40 (61%) completing the post-test, and 33 (50%) completing the delayed post-test. Year of training was not collected on the pretest, but first years comprised 39% and 42% of residents completing the post-test and delayed post-test, respectively. Score distribution is displayed in Fig. 1. The mean score increased significantly from 56 to 68% between the pretest and post-test (p = 0.0018). The delayed post-test mean score remained at 71%, with no significant decrease (p = 0.46). Comparison of pretest to delayed post-test was consistent in showing a significant increase of mean score (p < 0.001).

Verbal and written feedback from residents revealed appreciation for the more focused, interactive approach. There were several comments that residents preferred fellow-taught lessons, which were thought to be more appropriate in depth of material and more accessible. Some of the lectures by faculty were thought to be more fellow-level content. Faculty expressed difficulty reviewing the required information in half an hour, and some residents requested more time for individual topics such as cyanotic/acyanotic heart disease and the murmur lab.

Discussion

Pediatric residents who underwent a pediatric cardiology curriculum framed on short lectures and active learning had a statistically significant increase in mean score between the pretest and the post-test. Additionally, the average score was maintained 8 months after the last session of the curriculum, suggesting that knowledge gained through the curriculum had good mid-term retention.

Residents often have a large clinical burden and have limited time for formal education. The educational time they can afford should be high-impact, efficient, and engaging to optimize acquisition and retention of knowledge. The constructivist learning theory, rooted in a focus on big concepts, personal interactions, group-work, and encouraging questions, hopes to address these goals. It has roots in philosophy and education with Kant and Piaget, respectively. It is based on the premise that new knowledge is first interpretated in the context of existing knowledge or schema, then assimilated or accommodated, leading to learning [4, 5]. Piaget writes that experience is constantly “assimilated” through pre-existing concepts, referring to fitting new information into existing schema [6]. Alternatively, new information will occasionally necessitate revision or redevelopment of schema, known as “accommodation”. Vgotsky takes these ideas a step further with his sociocultural theory of development, which proposes that learning occurs when students work with teachers and peers to solve a problem beyond their current level of understanding [7]. These ideas play directly into the idea of the flipped classroom, where students do a large portion of self-directed learning outside the classroom and then refine and apply the knowledge with group-based activities in the classroom [8,9,10,11].

Pediatric residents have strong frameworks developed in medical school that consist of a basic understanding of cardiovascular anatomy, embryology, physiology, and hemodynamics. Depending on their year of training, they often have foundational knowledge in the care of healthy children, acute illness, and chronic disease. If they have completed any cardiology rotations or electives, some may have some basic understanding of congenital and acquired heart disease in children. This groundwork should allow the educator to focus on the principles of pediatric cardiology, incorporating these principles into the residents’ existing general pediatrics schema.

Using flipped classrooms, simulation, and other methods based on a constructivist educational approach, others have shown similar outcomes to our study. Broadly, a meta-analysis by Freeman et al. evaluated 225 papers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics disciplines comparing active learning versus traditional classroom learning. They found that students in active learning classrooms had higher evaluations scores than those in traditional learning. Moreover, those students in traditional lectures were 1.5 times more likely to fail than students in courses with active learning (odds ratio of 1.95, p ≤ 0.001) [12]. The effect remained across all disciplines and classroom sizes, although was most notable for classes ≤ 50 students. Focusing on medicine, a meta-analysis by Hew and Lo showed that across 28 studies evaluating the flipped classroom model for health professionals, there was a significant effect in favor of flipped classrooms over traditional classrooms (standardized mean difference = 0.33, 95% confidence interval 0.21–0.46, p < 0.001) [8]. A number of studies in graduate medical education have evaluated flipped classroom design. Review of the literature showed several articles in internal medicine and emergency medicine residency training. Generally, these studies showed that flipped classrooms are preferred by residents and fellows, and frequently are associated with improvement of knowledge, although not always better than traditional learning [13,14,15,16,17,18].

In pediatric cardiology, simulation has already been demonstrated to have beneficial association with improved clinical management of pediatric cardiology cases [19,20,21,22]. Mohan et al. showed that high-fidelity simulation led to improved test scores and confidence in pediatric residents versus those who did not undergo simulation [19]. Similarly, Harris et al. showed that guided simulation improved pediatric resident management of cardiac patients without significant decay of skills 4–6 months later [20]. Additionally, focused evaluations on ECG reading has shown that more advanced PGYs were able to correctly identify more ECG pairings on completion of a cardiology rotation [23, 24]. This would support the idea that active learning is useful in pediatric cardiology, although self-reported additional training reading ECGs was not beneficial in the work by Crocetti and Thompson [23]. Other authors have been quite innovative in their multimodal educational approach. Costello et al. used 3D printed models and simulation training with pediatric residents and showed improvement in knowledge and conceptualization of ventricular septal defects, as well as improvement managing postoperative complications in this defect [25].

In graduate medical education, the traditional hour-long, daily lectures are difficult for many reasons. Residents and faculty are frequently interrupted from lecture for patient care and 1 h is a long time to stay focused and engaging for both parties. The MUSC pediatric residency changed to the weekly academic half days with hope to improve resident attendance, decrease interruptions, improve faculty and resident satisfaction, and improve resident performance on in-training exams [26, 27]. The pediatric cardiology department developed a comprehensive curriculum by combining shorter lectures with a number of active learning modalities including simulation, case-based learning, and game-style review. The sessions that most fit the design of a flipped classroom were the murmur lab, Medical Emergency Team/code review, the interactive learning day sessions (simulation, ECG reading, and small group cases), and the Jeopardy!-style review. With these sessions, the focus was the application of knowledge and testing understanding. Both faculty and fellows need to work toward making the more traditional lectures a true flipped classroom by giving articles or excerpts from chapters to read prior to each session. This may also alleviate the feeling that lecturers did not have enough time to cover the required information.

Gamification, or the use of elements of game-design in non-game contexts, is another method that could be used more throughout the curriculum to increase learner engagement [28,29,30]. The friendly competition, question-based discussion, and leaderboard of the Jeopardy!-style review kept the residents engaged during one of the longest sessions (90 min). Potentially, having more questions during lectures and a running leaderboard throughout the curriculum could further captivate the residents’ attention. Based on comments from the residents and faculty, we need to continue to pare down the content to allow for more time for focus on high-yield topics and for cases and discussion. Many of the faculty attempted to take old lectures and fit them into the new format. They still require more encouragement to follow the recommended “lecture” style and include more interactive components, whether it be cases, questions, or other methods of active learning.

Furthermore, this work underlined the benefit of fellows on resident education. Overall, residents preferred fellow-delivered material, and the curriculum was developed by fellows. Most of the published research on the impact of fellows on resident education has been in surgical specialties due to the concern that fellows decrease resident clinical learning and experience [31,32,33]. However, Backes et al. showed that a neonatology fellows education curriculum increased scores assessing resident learning and the value of the rotation in the resident’s development as general pediatricians [34]. The mix of faculty and fellows in the pediatric cardiology curriculum was successful with some unplanned benefits, including better receptiveness to “alternative” teaching strategies and more resident-level content by fellow lecturers. This work does not have adequate data to determine why residents preferred the fellow-presented lessons which would be important to distinguish since fellow-delivered lessons also were more likely to use an interactive teaching modality. Additionally, there is insufficient data to determine if fellows improved resident learning. Nevertheless, the benefit of fellow involvement in the curriculum based on verbal feedback is provocative.

This work was limited in that multiple educational interventions between the time of pretest and post-test make it difficult to attribute any one intervention to gain of knowledge. Due to 1.5 years between the curriculum repeating and incomplete data on the year of training for residents taking each test, a comparison to the previous pediatric cardiology curriculum was not possible. Therefore, it is impossible to say if this curriculum had a higher improvement in mean scores compared to the previous curriculum based on the traditional lecture model. The composition of years of training may have influenced the improvement of scores between tests as well, if there was a higher ratio of first years on the pretest than the post-tests. Although we did not collect the years of training on the pretest, first years would have represented, at most, 44% of the test-takers compared to 39% and 42% for the post-test and delayed post-test, respectively. Additionally, a better assessment of resident knowledge ideally would have been generated from a larger set of questions on the tests. Ultimately, although improvement in content-based questions is desirable, it is unclear if our intervention ultimately resulted in improvement in care provided to patients. Ideally, our improvement in comprehension and retention of knowledge translates into better care of this complex population.

Future goals are to give key articles and reading excerpts to residents prior to each week’s sessions, moving the curriculum further toward a “flipped classroom”. This will allow the focus of the classroom time to be on answering questions and ensuring key principles are understood. Our hope was to further revise the curriculum for Spring 2020. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the curriculum had to be converted to online only. This made the ability for effective interaction and utilization of other learning modalities difficult. We were able to continue our use of short, 30-min lectures and nearly all lectures were given by pediatric cardiology fellows. Additionally, we managed to still have a murmur lab and Jeopardy!-style review.

Conclusions

Using an active, multimodal educational series, pediatric residents had a significant increase in mean test scores in pediatric cardiology and demonstrated good retention. This didactic strategy based on short, focused lectures and interactive workshops aligns more with constructivist learning theory and supports residents as learners.

Data and Material Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Burstein DS, Rossi AF, Jacobs JP, Checchia PA, Wernovsky G, Li JS, Pasquali SK (2010) Variation in models of care delivery for children undergoing congenital heart surgery in the United States. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 1:8–14

Pediatrics TABo (2017) General pediatrics content outline. www.abp.org

Garg A, Arora A, Hand IL (2016) Pediatric resident attitudes and knowledge of critical congenital heart disease screening. Pediatr Cardiol 37:1137–1140

Dennick R (2016) Constructivism: reflections on twenty five years teaching the constructivist approach in medical education. Int J Med Educ 7:200–205

Rees CE, Crampton PES, Monrouxe LV (2020) Re-visioning academic medicine through a constructionist lens. Acad Med 95:846–850

Flavell JH (1963) Developmental psychology of Jean Piaget. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York

Vgotsky LS (1978) Mind in society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Hew KF, Lo CK (2018) Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ 18:38

Lew EK (2016) Creating a contemporary clerkship curriculum: the flipped classroom model in emergency medicine. Int J Emerg Med 9:25

Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, Thorp AW, Thomas TL (2014) The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. West J Emerg Med 15:938–944

Erbil DG (2020) A review of flipped classroom and cooperative learning method within the context of Vygotsky theory. Front Psychol 11:1157

Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H, Wenderoth MP (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:8410–8415

Allenbaugh J, Spagnoletti C, Berlacher K (2019) Effects of a flipped classroom curriculum on inpatient cardiology resident education. J Grad Med Educ 11:196–201

Blair RA, Caton JB, Hamnvik OR (2020) A flipped classroom in graduate medical education. Clin Teach 17:195–199

Graham KL, Cohen A, Reynolds EE, Huang GC (2019) Effect of a flipped classroom on knowledge acquisition and retention in an internal medicine residency program. J Grad Med Educ 11:92–97

Riddell J, Jhun P, Fung CC, Comes J, Sawtelle S, Tabatabai R, Joseph D, Shoenberger J, Chen E, Fee C, Swadron SP (2017) Does the flipped classroom improve learning in graduate medical education? J Grad Med Educ 9:491–496

Rose E, Claudius I, Tabatabai R, Kearl L, Behar S, Jhun P (2016) The flipped classroom in emergency medicine using online videos with interpolated questions. J Emerg Med 51:284-291.e281

Wilson PM, Herbst LA, Gonzalez-Del-Rey J (2018) Development and implementation of an end-of-life curriculum for pediatric residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 35:1439–1445

Mohan S, Follansbee C, Nwankwo U, Hofkosh D, Sherman FS, Hamilton MF (2015) Embedding patient simulation in a pediatric cardiology rotation: a unique opportunity for improving resident education. Congenit Heart Dis 10:88–94

Harris TH, Adler M, Unti SM, McBride ME (2017) Pediatric heart disease simulation curriculum: educating the pediatrician. Congenit Heart Dis 12:546–553

Stone K, Reid J, Caglar D, Christensen A, Strelitz B, Zhou L, Quan L (2014) Increasing pediatric resident simulated resuscitation performance: a standardized simulation-based curriculum. Resuscitation 85:1099–1105

Subat A, Goldberg A, Demaria S, Katz D (2018) The utility of simulation in the management of patients with congenital heart disease: past, present, and future. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 22:81–90

Crocetti M, Thompson R (2010) Electrocardiogram interpretation skills in pediatric residents. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 3:3–7

Snyder CS, Bricker JT, Fenrich AL, Friedman RA, Rosenthal GL, Johnsrude CL, Kertesz C, Kertesz NJ (2005) Can pediatric residents interpret electrocardiograms? Pediatr Cardiol 26:396–399

Costello JP, Olivieri LJ, Su L, Krieger A, Alfares F, Thabit O, Marshall MB, Yoo SJ, Kim PC, Jonas RA, Nath DS (2015) Incorporating three-dimensional printing into a simulation-based congenital heart disease and critical care training curriculum for resident physicians. Congenit Heart Dis 10:185–190

Batalden MK, Warm EJ, Logio LS (2013) Beyond a curricular design of convenience: replacing the noon conference with an academic half day in three internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med 88:644–651

Zastoupil L, McIntosh A, Sopfe J, Burrows J, Kraynik J, Lane L, Hanson J, Seltz LB (2017) Positive impact of transition from noon conference to academic half day in a pediatric residency program. Acad Pediatr 17:436–442

Nevin CR, Westfall AO, Rodriguez JM, Dempsey DM, Cherrington A, Roy B, Patel M, Willig JH (2014) Gamification as a tool for enhancing graduate medical education. Postgrad Med J 90:685–693

Rutledge C, Walsh CM, Swinger N, Auerbach M, Castro D, Dewan M, Khattab M, Rake A, Harwayne-Gidansky I, Raymond TT, Maa T, Chang TP (2018) Gamification in action: theoretical and practical considerations for medical educators. Acad Med 93:1014–1020

van Gaalen AEJ, Brouwer J, Schönrock-Adema J, Bouwkamp-Timmer T, Jaarsma ADC, Georgiadis JR (2021) Gamification of health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 26:683–711

Grober ED, Elterman DS, Jewett MA (2008) Fellow or foe: the impact of fellowship training programs on the education of Canadian urology residents. Can Urol Assoc J 2:33–37

Jiang SY, Carlock KD, Campbell ST, Vorhies JS, Gardner MJ, Leucht P, Bishop JA (2021) The impact of subspecialty fellows on orthopaedic resident surgical experience: a multicenter study of 51,111 cases. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 29:263–270

Petrushnko W, Perry W, Fraser-Kirk G, Ctercteko G, Adusumilli S, O’Grady G (2015) The impact of fellowships on surgical resident training in a multispecialty cohort in Australia and New Zealand. Surgery 158:1468–1474

Backes CH, Reber KM, Trittmann JK, Huang H, Tomblin J, Moorehead PA, Bauer JA, Smith CV, Mahan JD (2011) Fellows as teachers: a model to enhance pediatric resident education. Med Educ Online 16:7205

Funding

The authors declare that they have no sources of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DRD: conceptualized and designed the study, performed the data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. ZJC and JRS: conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. CSJ: revised study design and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable. This is a quality improvement project and therefore did not require institutional review board approval.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable. This project was quality improvement.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delany, D.R., Coffman, Z.J., Shea, J.R. et al. An Interactive, Multimodal Curriculum to Teach Pediatric Cardiology to House Staff. Pediatr Cardiol 43, 1359–1364 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-02859-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-02859-3