Abstract

Cardiomyocytes exhibit robust proliferative activity during development. After birth, cardiomyocyte proliferation is markedly reduced. Consequently, regenerative growth in the postnatal heart via cardiomyocyte proliferation (and, by inference, proliferation of stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes) is limited and often insufficient to affect repair following injury. Here, we review studies wherein cardiomyocyte cell cycle proliferation was induced via targeted expression of cyclin D2 in postnatal hearts. Cyclin D2 expression resulted in a greater than 500-fold increase in cell cycle activity in transgenic mice as compared to their nontransgenic siblings. Induced cell cycle activity resulted in infarct regression and concomitant improvement in cardiac hemodynamics following coronary artery occlusion. These studies support the notion that cell-cycle-based strategies can be exploited to drive myocardial repair following injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: Cardiomyocyte Cell Cycle Activity

Many forms of cardiac disease are associated with the absence or loss of functional myocardium; for example, congenital diseases such as septal defects and hypoplastic chamber syndromes in many instances exhibit reduced levels of cell cycle activity during development, resulting in a deficit of cardiomyocytes. After birth, acquired injuries such as ischemia/reperfusion during surgical interventions or myocardial infarction, viral myocarditis, and anthracycline cardiotoxicity can all lead to cardiomyocyte loss and diminished cardiac function. The persistence of compromised cardiac function following congenital and acquired cardiac injury, particularly in postnatal hearts, indicates that the intrinsic regenerative reserve of the myocardium is at best limited.

Despite the absence of overt cardiac regeneration in postnatal hearts, many studies have been performed to determine if cardiomyocytes have the capacity to proliferate after birth and to determine if stem cells with cardiomyogenic potential persist in postnatal hearts. If such capacities were present in the postnatal heart, it might be possible to therapeutically manipulate the relevant pathways to promote regenerative growth. Pioneering work from Pavel Rumiantsev in the 1970s and 1980s utilized a number of experimental approaches to quantitate the levels of cardiomyocyte DNA replication and cell division during development and following injury in a large number of species, including humans [15]. These studies revealed that the level of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and cell division decreases rapidly after birth. Although cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity was detectable in juvenile and adult hearts, the level was exceedingly low. These findings are supported by the bulk of subsequent studies [18]. As it is likely that stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes would also exhibit cell cycle activity, these data suggest that de novo cardiomyogenic activity in postnatal hearts is also limited. Indeed, cell fate studies in mice [7] and humans [1] support this conclusion.

Given the low levels of intrinsic cardiac regeneration, considerable effort has been employed to experimentally activate cardiomyogenic stem cell activity and/or cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity, with the hopes that these manipulations could be translated to human hearts [13]. These studies have been greatly aided by the use of gene transfer techniques and, in particular, the use of genetically altered mice with either gain- or loss-of-function modifications. Using this approach, a number of genes have been identified as key cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulatory proteins [10]. In several instances, manipulation of these genes was able to promote regenerative growth following myocardial injury in postnatal hearts. This article will focus on our laboratory’s studies of the use of cyclin D2 to promote regenerative myocardial growth.

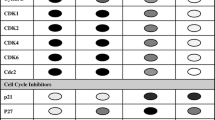

Forced Transit of the Restriction Point Can Induce Cardiomyocyte Cell Cycle Progression

Restriction point transit constitutes the key regulatory step in the commitment to a new round of cell division. Restriction point transit is regulated largely by the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and its obligate cofactors, the D-type cyclins [3, 16]. D-Type cyclin expression is induced by growth factors; when D-type cyclins accumulate in the nucleus, they bind to and activate CDK4. This active cyclin D/CDK4 complex phosphorylates members of the retinoblastoma (RB) gene family, which in turn frees members of the E2F transcription family to initiate a new round of cell cycle activity.

There are three D-type cyclins in mammals, designated cyclin D1, D2, and D3. All three are expressed in the developing heart and all three are rapidly downregulated after birth in parallel with the decreased levels of cardiomyocyte proliferation in postnatal hearts [20, 21]. In an effort to induce restriction point transit (and, hopefully, cell cycle progression) in postnatal mouse hearts, we generated transgenic mice expressing cyclin D1, D2, or D3 under the regulation of the cardiomyocyte-restricted myosin heavy chain (MHC) promoter [11, 21]. Although all three transgenic models exhibited similar postnatal cell cycle kinetics under baseline conditions, only mice expressing cyclin D2 (designated MHC-cycD2 mice) exhibited sustained cell cycle activity following injury. Consequently, this review focuses on the MHC-cycD2 model. Immune histology analyses revealed high levels of nuclear cyclin D2 expression in the MHC-cycD2 transgenic hearts but not in their nontransgenic siblings (Fig. 1, upper panels). Interestingly, cyclin D2 expression was accompanied by a marked induction of the endogenous CDK4 gene product (Fig. 1, middle panels).

Transgene expression and cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis in postnatal MHC-cycD2 hearts. Heart sections from MHC-cycD2 mice and their nontransgenic littermates were subjected to anti-cyclin D2 (upper panels) and anti-CDK4 (middle panels) immune histology (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, dark brown signal from diaminobenzidine reaction). Cyclin D2 expression results in a concomitant induction of the endogenous CDK4 gene product in transgenic hearts. Heart sections from MHC-cycD2/MHC-nLAC double transgenic mice and their MHC-nLAC single transgenic littermates were processed for cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis assay (mice received an injection of tritiated thymidine prior to sacrifice). The presence of silver grains over blue nuclei is indicative of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and is readily seen in sections from mice carrying the MHC-cycD2 transgene

To monitor the impact of cyclin D2 expression on postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity, the MHC-cycD2 mice were intercrossed with MHC-nLAC mice, which express a nuclear β-galactosidase reporter under the control of the MHC promoter [19]. At 12 weeks of age, progeny from the cross were given a single injection of tritiated thymidine. Four hours later, the mice were sacrificed; the hearts were harvested, sectioned, stained with X-GAL (which produces a blue signal when metabolized by β-galactosidase), and then coated with photographic emulsion. After the photographic emulsion is developed, the presence of silver grains (due to tritiated thymidine exposure of emulsion) over blue nuclei (due to cardiomyocyte-restricted expression of the nuclear β-galactosidase) is indicative of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis. Mice inheriting both the MHC-cycD2 and MHC-nLAC transgenes had a cardiomyocyte tritiated thymidine labeling index of 0.26% [11]; an example of an S-phase cardiomyocyte using this assay is shown in Fig. 1 (lower panels). In contrast, mice inheriting the MHC-nLAC transgene alone had tritiated thymidine labeling index of 0.0005% [11, 17], although noncardiomyocyte DNA synthesis could easily be detected in these animals. Thus, expression of cyclin D2 is sufficient to drive DNA synthesis in postnatal cardiomyocytes.

Cyclin D2 Expression Promotes Structural Repair Following Myocardial Infarction

Given that the MHC-cycD2 mice exhibit an approximately 500-fold increase in tritiated thymidine labeling index as compared to their nontransgenic siblings, additional experiments were performed to determine if cardiomyocyte cell cycle induction could reverse myocardial injury in postnatal hearts. Accordingly, MHC-cycD2 mice and their nontransgenic littermates were subjected to permanent coronary artery occlusion [6]. Hearts were harvested at 7, 60, and 180 days postinjury, and infarct size was determined using the approach developed by Pfeffer and colleagues [12]. In nontransgenic mice, approximately 53% of the left ventricle was infarcted at 7 days postinjury (Fig. 2a). Infarct size remained constant through 180 days postinjury, although there was a slight trend toward infarct expansion. At 7 days postinjury, MHC-cycD2 transgenic mice exhibited a similar infarct size, as was seen in their nontransgenic littermates, indicating that expression of cyclin D2 was not acutely cardioprotective. However, a marked reduction in infarct size was seen at 60 and 180 days postinjury.

Expression of cyclin D2 results in infarct regression. a Infarct size in nontransgenic and MHC-cycD2 transgenic mice at 7, 6, and 180 days postinjury. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between MHC-cycD2 hearts and. noninfarcted hearts at the indicated time point. b Representative sections from infarcted MHC-cycD2 transgenic hearts and their nontransgenic siblings at 7 and 180 days postinjury. Sections were sampled at 1-mm intervals from the apex to the base and were stained with Azan

Structural repair was readily apparent when examining survey micrographs of transverse sections from the MHC-cycD2 transgenic hearts sampled at 1-mm intervals from the apex to the base (Fig. 2b). The sections were stained with Azan (viable myocardium stains magenta, scar tissue stains gray). At 7 days postinjury, transmural damage was apparent from the apex to the base. However, by 180 days postinjury, cardiomyocytes could be detected in apically located sections of MHC-cycD2 hearts. Because these apical regions were devoid of cardiomyocytes at 7 days postinjury, they have been designated as regenerated myocardium. In contrast, apical regions in nontransgenic hearts lacked any evidence of regenerative growth over the course of the experiment.

Consistent with this interpretation, MHC-cycD2 hearts exhibited sustained, high levels of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis (ranging between 0.5% and 1% following a single injection of tritiated thymidine), and cardiomyocytes with phosphorylated histone H3 immune reactivity (a marker for mitosis [23]) were readily detected [11]. Collectively, these data demonstrate that cyclin D2 expression resulted in a remarkable degree of regenerative growth following injury.

Cyclin D2 Expression Promotes Functional Recovery Following Myocardial Infarction

Given the structural recovery observed in the infarcted MHC-cycD2 mice, it is likely that there would be a concomitant improvement in cardiac function provided that the newly regenerated myocardium participated in a functional syncytium with the remote, noninfarcted myocardium. Immune histology analyses revealed that regenerated cardiomyocytes were connected to one another via well-developed junctional complexes containing connexin43 (the major component of the cardiac gap junction; Fig. 3a). To determine if the regenerated myocardium was functionally integrated, MHC-cycD2 hearts harvested at 180 days postinjury were perfused on a Langendorff apparatus, and the apically located (i.e., regenerated) myocardium was imaged for the presence of intracellular calcium transients using the calcium-sensing dye rhod-2 in combination with two-photon laser scanning microscopy [14]. Intracellular calcium transients were readily observed in the regenerated myocardium during sinus rhythm (recordings from three adjacent cardiomyocytes are shown in Fig. 3b, left panels). These intracellular calcium transients were in synchrony with and indistinguishable from those in the remote, noninfarcted myocardium (Fig. 3b, right panels). These data indicate that the regenerated myocardium can participate in a functional syncytium with the host myocardium.

Regenerated myocardium in MHC-cycD2 hearts is functionally integrated. Samples are from MHC-cycD2 hearts at 180 days postinfarction. a Apically located regenerated cardiomyocytes are well developed (left panel, Azan stain) and are interconnected via well-developed junctional complexes containing anti-connexin43 immune reactivity (right panel, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, dark brown signal from diaminobenzidine reaction). b Intracellular calcium transients (as evidenced via changes in the fluorescence of the calcium-sensing dye rhod2) recorded from three apically located cardiomyocytes in the regenerated myocardium (left panels). Intracellular calcium transients in cardiomyocytes located in the regenerated myocardium were in synchrony with and indistinguishable from those in the remote myocardium (right panels)

To determine the impact of myocardial regeneration on cardiac hemodynamics, MHC-cycD2 mice and their nontransgenic littermates were subjected to permanent coronary artery occlusion. At 7, 60, and 180 days postinjury, the mice were anaesthetized and ventilated, the left ventricular was accessed via the right common carotid artery, and pressure–volume relationships were recorded using a 1.4-French Millar catheter [6]. These experiments employed the same series of mice used earlier for infarct size measurement (hemodynamic measurements were performed prior to sacrifice). Pressure–volume analyses were also performed in time-point-matched, sham-infarcted mice.

Cardiac function was markedly suppressed in the infarcted nontransgenic animals at all times analyzed. Figure 4 shows the values calculated for the left ventricular peak positive developed pressure/end diastolic volume relationship (dP/dt max/EDV, left panel, open bars) and the end systolic pressure–volume relationship (ESPVR, right panel, open bars). Functional parameters were normalized to the values obtained from time-point-matched, sham-infarcted mice. At 7 days postinfarction, cardiac function in the MHC-cycD2 was suppressed to a similar extent as was seen for the nontransgenic animals. However, a marked and progressive increase in cardiac function was apparent at 60 and 180 days postinfarction (Fig. 4, closed bars). Remarkably, at the 180-day time point, dP/dt max/EDV and ESPVR were not statistically different in infarcted versus sham-infarcted MHC-cycD2 mice (1172.7 ± 222.7 vs. 1336 ± 119 mm Hg/s/μl and 29.0 ± 3.1 vs. 31.2 ± 2.8 mm Hg/μl, respectively).

Left ventricular performance was assessed by pressure–volume measurements. The left panel shows the left ventricular peak positive developed pressure/end diastolic volume (dP/dt max/EDV) relationship for nontransgenic (open bars) and MHC-cycD2 mice (closed bars) at 7, 60, and 180 days after myocardial infarction. The values shown were normalized to those obtained from sham-operated mice from the same time points. The right panel shows the end systolic pressure–volume relationship (EDPVR)

Summary and Future Directions

The data reviewed here indicate that constitutive expression of cyclin D2 is sufficient to promote cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity in postnatal hearts and that this cell cycle activity results in myocardial regeneration and functional recovery following injury. To date, a number of gene products have been shown to promote structural and/or functional recovery in injured hearts; for example, deletion of the p38 MAP kinase gene results in FGF1-inducible cell cycle progression in postnatal cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo [4]. Transient pharmacologic inhibition of p38 MAP kinase, in combination with FGF1 treatment, resulted in improved cardiac structure and function at 3 months postinfarction in adult rats [5]; however, the degree to which proproliferation, antiapoptotic and/or antihypertrophic activities contributed the observed improvement is not clear. Transgenic mice expressing cyclin A2 (which can regulate both restriction point transit and mitosis entry) exhibited enhanced cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity in early postnatal life, but not in adults [2]. Viral delivery of cyclin A2 in infarcted rat hearts had a positive impact on cardiac structure and function [24], although the cell type responsible for the observed improvement was not clear. As reported elsewhere, genetic deletion of c-kit renders postnatal cardiomyocytes able to reenter the cell cycle following injury [8]. Finally, cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of the RB gene, in the presence of global deletion of p130 (another member of the RB gene family), gave rise to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia in postnatal hearts [9].

These are but a few examples of genetic pathways that can be exploited to induce cell cycle activity in postnatal cardiomyocytes. However, there remain a number of issues that must be experimentally addressed to validate these genes as potential targets to induce regenerative growth; for example, most studies utilized genetic manipulations that occurred prior to cardiomyocyte terminal differentiation. Hence, it is possible that similar manipulation in adult cardiomyocytes might not have the same result. This is likely not the case with targets aimed at modulating restriction point transit, as viral delivery of a cyclin D1 molecule carrying a nuclear localization sequence, in combination with CDK4, was sufficient to induce cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity in adult rat hearts [22]. Similarly, as indicated earlier, pharmacologic modulation of p38 MAP kinase and FGF1 resulted in cell cycle progression in adult hearts. Perhaps even more important is to determine if the genetic pathways in question are also operative in human cardiomyocytes. The ability to isolate and engraft cardiomyogenic precursors from human embryonic stem cells [25] as well as other cardiomyogenic precursors will greatly facilitate such analyses. Finally, once manipulation of a given genetic pathway is validated as a target for inducing regenerative growth, it would be highly desirable to develop molecules that mimic the genetic modification, thereby obviating the need for gene transfer-based interventions.

References

Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Kanar Alkass, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisen J (2008) Turnover of human cardiomyocytes. Circulation 118(Suppl):Abstract 3526

Chaudhry HW, Dashoush NH, Tang H, Zhang L, Wang X, Wu EX, Wolgemuth DJ (2004) Cyclin A2 mediates cardiomyocyte mitosis in the postmitotic myocardium. J Biol Chem 279:35858–35866

Dowdy SF, Hinds PW, Louie K, Reed SI, Arnold A, Weinberg RA (1993) Physical interaction of the retinoblastoma protein with human D cyclins. Cell 73:499–511

Engel FB, Schebesta M, Duong MT, Lu G, Ren S, Madwed JB, Jiang H, Wang Y, Keating MT (2005) p38 MAP kinase inhibition enables proliferation of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes. Genes Dev 19:1175–1187

Engel FB, Hsieh PC, Lee RT, Keating MT (2006) FGF1/p38 MAP kinase inhibitor therapy induces cardiomyocyte mitosis, reduces scarring, and rescues function after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:15546–15551

Hassink RJ, Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Rubart M, Soonpaa MH, de la Riviere AB, Doevendans PA, Field LJ (2008) Cardiomyocyte cell cycle activation improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 78:18–25

Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, Robbins J, Lee RT (2007) Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med 13:970–974

Li M, Naqvi N, Yahiro E, Liu K, Powell PC, Bradley WE, Martin DI, Graham RM, Dell’Italia LJ, Husain A (2008) c-kit is required for cardiomyocyte terminal differentiation. Circ Res 102:677–685

MacLellan WR, Garcia A, Oh H, Frenkel P, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Schneider MD (2005) Overlapping roles of pocket proteins in the myocardium are unmasked by germ line deletion of p130 plus heart-specific deletion of Rb. Mol Cell Biol 25:2486–2497

Pasumarthi KB, Field LJ (2002) Cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation. Circ Res 90:1044–1054

Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Soonpaa MH, Field LJ (2005) Targeted expression of cyclin D2 results in cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and infarct regression in transgenic mice. Circ Res 96:110–118

Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA, Fletcher PJ, Braunwald E (1991) Progressive ventricular remodeling in rat with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol 260:H1406–H1414

Rubart M, Field LJ (2006) Cardiac regeneration: repopulating the heart. Annu Rev Physiol 68:29–49

Rubart M, Wang E, Dunn KW, Field LJ (2003) Two-photon molecular excitation imaging of Ca2+ transients in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284:C1654–C1668

Rumiantsev PP (1991) Growth and hyperplasia of cardiac muscle cells. Harwood Academic, London

Schang LM (2003) The cell cycle, cyclin-dependent kinases, and viral infections: new horizons and unexpected connections. Prog Cell Cycle Res 5:103–124

Soonpaa MH, Field LJ (1997) Assessment of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis in normal and injured adult mouse hearts. Am J Physiol 272:H220–H226

Soonpaa MH, Field LJ (1998) Survey of studies examining mammalian cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis. Circ Res 83:15–26

Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Klug MG, Field LJ (1994) Formation of nascent intercalated disks between grafted fetal cardiomyocytes and host myocardium. Science 264:98–101

Soonpaa MH, Kim KK, Pajak L, Franklin M, Field LJ (1996) Cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and binucleation during murine development. Am J Physiol 271:H2183–H2189

Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Pajak L, Jing S, Wang H, Franklin MT, Kim KK, Field LJ (1997) Cyclin D1 overexpression promotes cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and multinucleation in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 99:2644–2654

Tamamori-Adachi M, Ito H, Nobori K, Hayashida K, Kawauchi J, Adachi S, Ikeda MA, Kitajima S (2002) Expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4 causes hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in culture: a possible implication for cardiac hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296:274–280

Wei Y, Mizzen CA, Cook RG, Gorovsky MA, Allis CD (1998) Phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 is correlated with chromosome condensation during mitosis and meiosis in Tetrahymena. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7480–7484

Woo YJ, Panlilio CM, Cheng RK, Liao GP, Atluri P, Hsu VM, Cohen JE, Chaudhry HW (2006) Therapeutic delivery of cyclin A2 induces myocardial regeneration and enhances cardiac function in ischemic heart failure. Circulation 114:I206–I213

Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, Bonham K, Abbott GW, Linden RM, Field LJ, Keller GM (2008) Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature 453:524–528

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Hassink, R.J., Rubart, M. et al. Cell-Cycle-Based Strategies to Drive Myocardial Repair. Pediatr Cardiol 30, 710–715 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-009-9408-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-009-9408-3