Abstract

Background

Osteoradionecrosis of the jaw is a severe complication of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients. If conservative treatment and surgical debridement have been unsuccessful, the preferred treatment for symptomatic mandibular osteoradionecrosis (mORN) is radical surgery and subsequent reconstruction with a free vascularized flap. This study aims to assess the outcomes of free vascularized flap reconstruction in mORN.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on all patients who underwent a free vascularized flap reconstruction for mORN between 1995 and 2021 in Amsterdam UMC – VUmc, The Netherlands.

Results

In our cohort study, three of the twenty-eight flap reconstructions failed (10.7%). No recurrences of mORN were observed during a mean follow-up of 8 years.

Conclusions

The success rate of free vascularized flap reconstruction for mORN is high. The fibula is the preferred free flap for mandibular reconstruction in mORN cases. However, this type of surgery is at risk for complications and patients need to be informed that these complications may require surgical re-intervention.

Level of evidence: Level IV, Therapeutic; Risk/Prognostic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a severe complication of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients. Up to 30% of the patients who undergo radiotherapy are affected by ORN, and at least, half of the patients who develop clinical signs and symptoms require surgical intervention (1, 2). ORN has been described by Marx in 1983 as a chronic non-healing wound due to radiation causing hypoxic-hypocellular-hypovascular tissue, eventually leading to tissue breakdown. In head and neck cancer patients, the mandible is most frequently affected (3). Risk factors for the development of ORN include mandibular surgery prior to radiotherapy (e.g., tooth extractions), radiation dose, radiation field size, and radiation fractionation. In addition, alcohol and smoking have been reported to play an important role. ORN clinically presents as a necrotic area that results in functional impairment and pain and may lead to orocutaneous fistulae and eventually pathologic fractures (4, 5). Although conservative therapy, based on local application of antiseptics (e.g., chlorhexidine gel), the systemic administration of antibiotics, minimal surgical debridement, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) can offer promising results in mild cases of ORN, it is insufficient in the more extensive necrotic defects. In these latter cases, partial mandibulectomy (segmental mandibular resection) and reconstructive surgery are indicated. The most frequently used operative technique for reconstruction in mandibular osteoradionecrosis (mORN) cases is the free vascularized flap. Several donor sites have been reported, such as the fibula, iliac crest, scapula, and radial forearm. The free fibula flap (FFF) is the most popular and widely accepted flap for mandibular reconstructions (6). Little is actually known about the incidence of complications of free vascularized flap reconstructions in mORN cases (7). A comprehensive overview of complication rates of surgical interventions for mORN is still lacking.

The aim of this study is to produce a comprehensive overview of the outcomes and complications of free vascularized flap reconstructions in mORN cases based on a retrospective study on patients who had been treated in our hospital and had a long-term follow-up.

Materials and methods

Retrospective cohort study

All patients who underwent microvascular flap reconstruction for mORN between 1995 and 2021 in Amsterdam UMC – VUmc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, were included in this study. Data regarding the patients’ demographics, preoperative variables including radiation dose, tumor type, treatment date, and peri-operative hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy and data on reconstructive treatment were collected. Patients were eligible if they had a minimum follow-up of 3 months. The clinical diagnosis of mORN was supported by radiological imaging. Surgical treatment was performed after failed conservative treatment and in case of severe signs and symptoms of ORN, such as pain, a pathological fracture, fistula, or a non-healing mucosal defect with exposed mandibular bone. The segmental mandibular defect was graded according to the Brown’s classification, based on the four corners of the mandible (8). An interdisciplinary team approach was used in all patients (ENT/head and neck-surgeon, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, and reconstructive surgeon). All flap harvests were performed by the same reconstructive surgeon (HW). The extent of mandibular resection was determined according to clinical and radiographic (CT scan) criteria. All necrotic tissue was excised until healthy bleeding bone was identified. All mandibular resection specimens were sent for histopathologic examination to confirm the diagnosis of osteoradionecrosis and to rule out tumor recurrence.

The primary study outcomes were postoperative outcomes including flap survival and postoperative complications (early and late complications). Late complications were defined as those that occurred 30 or more days after reconstructive surgery for mORN. Data were collected from medical files. Data related to the diagnosis, radiation history, previous treatment(s), recipient, and donor sites were collected.

Data analyses

A meta-analysis was performed using random effects model and presented as pooled prevalences and range. All statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.5.3.), package meta.

Results

Retrospective cohort study

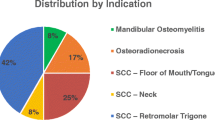

Twenty-eight patients were included in this cohort study, 17 males and 11 females with a mean age of 63 years (range: 44–79). All patients had received radiotherapy for various malignant tumors in the head and neck region. All patients developed mORN and had subsequently undergone a free flap reconstruction of the mandibular defect. The demographic data of the 28 patients are shown in Table 1. Patients had been previously diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 27 cases and pleomorphic sarcoma in one case. Twenty patients (71%) had undergone previous flap reconstruction after initial tumor resection (19 free flaps and 1 pedicled flap). The mean radiotherapy dose was 62 Gy (range: 46–70). The interval between completion of radiotherapy and the clinical diagnosis of mORN ranged from 30 days to 22 years (mean: 2 years and 11 months). All patients diagnosed with mORN were initially treated conservatively and eighteen patients (64%) additionally underwent hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy. Segmental mandibular resections were performed in patients with mORN who did not respond to initial conservative treatment. The interval between the completion of radiotherapy and surgery (segmental resection) ranged from 6 months to 25 years (mean: 4.6 years). Patients were reconstructed with a free fibula flap (FFF) (n = 27) and a free radial forearm flap (n = 1). The surgical data are shown in Table 2. Histopathological examination of all mandibular resection specimens supported the diagnosis of mORN. No evidence of recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma or pleomorphic sarcoma was diagnosed in the resection specimens. Hospital admissions ranged from 7 to 88 days (mean: 24 days). There was no statistically significant difference in duration of hospitalization between patients that previously underwent flap reconstructions versus radiation therapy only (mean: 25 vs. 21 days; range: 7–88 vs. 11–46).

Of the 28 free flap reconstructions, three free fibula flaps failed (10.7%), resulting in an overall free flap survival of 89.3%. Two flaps were lost as a result of thrombosis. One flap failed because of a persistent low blood flow due to persistent hypotension and low cardiac output intraoperatively. Secondary reconstructions were successfully performed with a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in two cases and a contralateral free fibula flap in one case.

There were 10 early postoperative complications that did not result in flap failure (Table 3). One case failed partially as a result of partial necrosis, requiring an additional pectoralis major flap reconstruction. The most common complications were wound infections (n = 4). Postoperative bleeding was detected in two patients. Thirteen patients developed late complications including donor site complications (n = 3), orocutaneous fistulae (n = 2), and carotid blow out (n = 1). The mean follow-up after reconstruction was 8 years and 2 months (range: 7 months to 15 years and 8 months). No evidence of mORN recurrence was observed in any patient during follow-up. Four patients developed a recurrence of SCC. The recurrences of SCC presented 3 to 30 months after reconstruction surgery, with a mean of 17 months.

Twelve patients (43%) underwent implant-based dental rehabilitation. In total, 41 regular neck, soft-tissue level Straumann dental implants (diameter of 4.1 mm, length of 10 or 12 mm) were secondarily placed in the fibular bone in a two-stage procedure. The implants were retrieved after at least 3 months osseointegration time. All dental implants showed good osseointegration. Soft-tissue management consisted of debulking and/or (partial) excision of the overlying skin paddle, followed by a vestibuloplasty with keratinized palatal mucosal grafting to create a more favorable peri-implant soft tissue condition and prosthetic platform. Four to 5 weeks after completion of the second stage, the prosthetic rehabilitation was started. In the majority of patients, the function was restored with implant-supported, bar-retained removable dentures (Fig. 1a–e). No dental implants were lost during follow-up.

a Pre-operative panoramic radiograph: osteolytic lesions and pathological fracture in the left edentulous mandible based on osteoradionecrosis. b Post-operative panoramic radiograph: mandibular reconstruction with a 2.7-mm titanium plate and osteo-cutaneous fibula flap after radical resection of the osteoradionecrosis. c Panoramic radiograph: retention bar on four dental implants in the reconstructed mandible; situation 9 months after the primary osseous reconstruction. d Clinical situation: retention bar on four dental implants in the reconstructed mandible; the implants are surrounded by keratinized mucosa originating from the hard palate. e Clinical situation: implant-supported, bar-retained removable denture in the mandible to restore oral function

Discussion

This study aimed to present a comprehensive overview of the clinical outcomes after microvascular free flap reconstructive surgery as a treatment for mandibular osteoradionecrosis (mORN) based on a retrospective cohort study.

Osteoradionecrosis is a severe condition, which usually occurs within the first 3 years after radiotherapy (9, 10). This was confirmed in our study of 28 mORN cases.

The treatment of early stage ORN is usually conservative, based on local care, systemic administration of antibiotics, minimal surgical debridement, and HBO therapy. HBO therapy was introduced in the early 1900s. Its supposed effectiveness was based on hypothetical theories on the causes of ORN. The therapy rapidly became common practice. Review of the literature showed that 56% (range 25–98%) of the patients received preoperative HBO therapy, while in our cohort 64% had received HBO therapy (10,11,12,13, 13,14,15,16,17). We did not find a significant benefit from the preoperative use of HBO. To date, strong evidence of the value of HBO therapy is lacking. More discussion has risen after Alam et al. (11) reported a high prevalence of patients who presented postoperative complications despite HBO therapy. Annane et al. (18) found even negative results, with the HBO therapy compared to a placebo treatment, which makes it questionable whether it should be routinely applied.

Radical surgery and reconstructive procedures are reserved for symptomatic ORN cases where conservative treatment has been unsuccessful. Radical resection followed by free flap reconstruction has been recommended as the method of choice in the surgical management of mORN (12). In our experience, the free fibula flap (FFF) is the first choice for mandibular reconstruction in mORN cases. The FFF benefits from its good bone quality with substantial cortical thickness and length (up to 25–30 cm), which permits multiple osteotomies (6). The skin paddle is reliable and can be large, to reconstruct larger defects. It is also thin, allowing good modeling. In addition, the vascular pedicle can be lengthened up to 15 cm, by discarding the proximal portion of the fibula, and using the distal portion for the reconstruction. This is important, because in these patients with a heavily irradiated neck, identification of adequate recipient vessels in the ipsilateral neck may be difficult. A long vascular pedicle allows more options of recipient vessels, without having to use a vein graft (13). In our series, 71% of the patients had had major head and neck surgery with microvascular reconstruction prior to the development of mORN. In addition, the use of fibular bone allows the placement of dental implants simultaneously or in a later stage. Finally, donor site morbidity is relatively low (1). In our cohort, 27 patients (96%) were reconstructed with a FFF. In the literature, only 54% of the reconstructions were performed with a FFF.

Although the FFF is known as a safe and reliable option for surgical reconstruction, in our cohort study the flap failure rate was 10.3% (3 out of 28), which is somewhat higher than reported in the literature (range: 0–14.3%). Compared to previously published studies, we reported a similar complication rate. As the mean follow-up after reconstruction was more than 8 years, we were also able to document the late complications, being 64% of the complications in our cohort study.

Remarkably, in our study, no recurrence of mORN was observed in any patient during follow-up. In the literature, a mean ORN recurrence rate of 10% (range 0–25%) is reported (10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 19,20,21,22,23). In 59% of these cases, a recurrence of ORN was found in the mandibular bone adjacent to the treated site of ORN; in 26%, it was found in the contralateral mandibular or maxillary bodies (10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 19,20,21,22,23). Our method for resecting the affected bone is based on the interpretation of CT imaging and careful intraoperative inspection of the bone tissue. The ORN-affected bone is resected up to the point where clear bleeding bone is identified at the mandibular margins. A recently published study presents a novel method for 3D visualization of radiotherapy isodose lines in relation to 3D bone models derived from CT data at the time of ORN occurrence. This method enables the evaluation of ORN risk areas, exact resection planning of ORN-affected bone, and the planning of screw locations for reconstruction plates outside the high-dose area (24). This tool has been recently added to our preoperative work-up for the treatment of severe mORN cases.

Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible (mORN) is a serious complication of radiation therapy. For an effective treatment of mORN, complete resection of all necrotic bone tissue is required with immediate reconstruction. Even though the flap failure rate in our series of ORN cases (10%) is approximately twice the failure rate of our primary mandibular reconstructions (5%), we still consider this method successful. The difference may be explained by the fact that this group of patients has had extensive surgery and radiotherapy in the affected area and also commonly has comorbidities and a suboptimal general health. The fibula is the preferred free flap for mandibular reconstruction in mORN cases. However, this type of surgery is at risk for complications. Patients need to be informed that these complications may require surgical re-intervention or even revision of the reconstruction.

Change history

06 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-022-02002-8

References

Baron S, Salvan D, Cloutier L, Gharzouli I, Le Clerc N (2016) Fibula free flap in the treatment of mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 133(1):7–11

Cannady S, Dean N, Kroeker A, Albert TA, Rosenthal EL, Wax MK (2011) Free flap reconstruction for osteoradionecrosis of the jaws-outcomes and predictive factors for success. Head Neck 33(3):424–428

Lyons AJ, Nixon I, Papadopoulou D, Crichton S (2013) Can we predict which patients are likely to develop severe complications following reconstruction for osteoradionecrosis? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51(8):707–713

Madrid C, Abarca M, Bouferrache K (2010) Osteoradionecrosis: an update. Oral Oncol 46(6):471–4

Mücke T, Koschinski J, Rau A et al (2013) Surgical outcome and prognostic factors after treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 139(3):389–394

Lee M, Chin RY, Eslick G, Sritharan N, Paramaesvaran S (2015) Outcomes of microvascular free flap reconstruction for mandibular osteoradionecrosis: a systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 43(10):2026–2033

Chaine A, Pitak-Arnnop P, Hivelin M, Dhanuthai K, Bertrand JC, Bertolus C (2009) Postoperative complications of fibular free flaps in mandibular reconstruction: an analysis of 25 consecutive cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 108(4):488–495

Brown J, Barry C, Ho M, Shaw R (2016) A new classification for mandibular defects after oncological resection. Lancet Oncol 17(1):e23-30

Dai T, Tian Z, Wang Z, Qiu W, Zhang Z, He Y (2015) Surgical management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws. J Craniofac Surg 26(2):e175–e179

Suh JD, Blackwell KE, Sercarz JA, Cohen M, Liu JH, Tang CG, Nabili V (2010) Disease relapse after segmental resection and free flap reconstruction for mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(4):586–591

Alam DS, Nuara M, Christian J (2009) Analysis of outcomes of vascularized flap reconstruction in patients with advanced mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141(2):196–201

Ang E, Black C, Irish et al (2003) Reconstructive options in the treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton. Br J Plast Surg 56(2):92–99

Chang DW, Oh HK, Robb GL, Miller MJ (2001) Management of advanced mandibular osteoradionecrosis with free flap reconstruction. Head Neck 23(10):830–835

Chandarana SP, Chanowski EJP, Casper KA et al (2013) Osteocutaneous free tissue transplantation for mandibular osteoradionecrosis. J Reconstr Microsurg 29(1):5–14

Celik N, Wei FC, Chen HC et al (2002) Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible after oromandibular cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 109(6):1875–1881

Santamaria E, Wei FC, Chen HC (1998) Fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap for reconstruction of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg 101(4):921–929

Jacobson AS, Zevallos J, Smith M et al (2013) Quality of life after management of advanced osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 42:1121–1128

Annane D, Depondt J, Aubert P et al (2004) Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radionecrosis of the jaw: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial from the ORN96 study group. J Clin Oncol 22(24):4893–4900

Baumann DP, Yu P, Hanasono MM, Skoracki RJ (2011) Free flap reconstruction of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: a 10-year review and defect classification. Head Neck 33(6):800–807

Fan S, Wang YY, Lin ZY (2016) Synchronous reconstruction of bilateral osteoradionecrosis of the mandible using a single fibular osteocutaneous flap in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 38:E607–E612

Ioannides C, Fossion E, Boeckx W, Hermans B, Jacobs D (1994) Surgical management of the osteoradionecrotic mandible with free vascularised composite flaps. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 22(6):330–334

Bettoni J, Olivetto M, Duisit J, Caula A, Bitar G, Lengele B, Testelin S, Dakpé S, Devauchelle B (2019) Treatment of mandibular osteoradionecrosis by periosteal free flaps. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 57(6):550–556

Yamashita J, Akashi M, Takeda D, Kusumoto J, Hasegawa T, Hashikawa K (2021) Occurrence and treatment outcome of late complications after free fibula flap reconstruction for mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Cureus 13(3):e1383

Kraeima J, Steenbakkers RJHM, Spijkervet FKL, Roodenburg JLN, Witjes MJH (2018) Secondary surgical management of osteoradionecrosis using three-dimensional isodose curve visualization: a report of three cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47(2):214–219

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This is an observational study. The Amsterdam UMC Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Informed consent

Participants have consented to the submission to the journal.

Conflict of interest

S.C.M. van den Heuvel, T.R.I. van den Dungen, E.A.J.M. Schulten, M.G. Mullender, H.A.H. Winters declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article, author name “T.R.I. den Dungen” should be corrected to “T.R.I. van den Dungen”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Heuvel, S.C.M., van den Dungen, T.R.I., Schulten, E.A.J.M. et al. Free vascularized flap reconstruction for osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: a 25-year retrospective cohort study. Eur J Plast Surg 46, 59–65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-022-01980-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-022-01980-z