Abstract

We apply the specialization technique based on the decomposition of the diagonal to the intersection of a quadric and cubic hypersurface in \(\mathbb {P}^6\). We find an explicit example defined over \(\mathbb {Q}\) that is smooth, and does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal, and is therefore not retract rational. The proof uses the specialization of Nicaise and Ottem (Tropical degenerations and stable rationality, 2020), who proved that the very general complete intersection of this type is stably irrational using the motivic volume.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Determining which varieties are rational is a central problem in birational geometry. Castelnuovo’s criterion for rationality gives a satisfying answer for surfaces over the complex numbers, but in higher dimensions, or over other fields, the rationality problem has proven to be harder. Nevertheless, studying rationality, various other weaker notions of rationality, and the relation between them, has been an active and fruitful area of research.

Here we will primarily consider stable rationality and retract rationality. Recall that a variety X is stably rational if \(X \times \mathbb {P}^n\) is rational for some n and X is retract rational if the identity map on X factors rationally through a projective space. In particular, if \(X \times Y\) is rational for a variety Y, then X is retract rational, so any stably rational variety is retract rational. The question of whether retract rationality implies stable rationality is a major open question.

A recent breakthrough in studying retract rationality is the specialization technique introduced by Voisin in [19]. This technique is based on the decomposition of the diagonal. The technique has then been developed further by Colliot-ThThélène and Pirutka [4] to allow for more general specializations, in particular to positive characteristic. Further work by Schreieder in [13] allowed specializing to varieties with singularities, without constructing explicit resolutions.

Some of the varieties proven to be non retract rational using the specialization technique based on the decomposition of diagonal are general double solids [19], general quartic hypersurfaces [4], general quadric surface bundles over rational surfaces [7], general hypersurfaces in projective space of sufficiently high degree [14, 18] and complete intersetions in projective space of sufficiently high degree [3].

Using specialization to positive characteristic to prove irrationality of hypersurfaces of sufficiently high degree already appears in Kollár [8], but there one specializes to a variety that is not ruled, rather than to a variety that merely has no decomposition of the diagonal. In [18], Totaro combines the specialization to positive characteristic with the decomposition of the diagonal technique to obtain better bounds on the degree. The specialization technique of Kollár is generalized to complete intersections in the PhD-thesis of Braune [1].

The goal of this paper is to prove retract irrationality for a specific complete intersection. We will use techniques from [13, 14] to find an example of a smooth (2, 3) complete intersection in \(\mathbb {P}^6\) with integer coefficients that is not retract rational. From this it follows that also the very general such complete intersection is not retract rational. One motivation for studying this particular case is that the very general complete intersection of this type is known to be stably irrational over \(\mathbb {C}\). Using a different degeneration technique introduced by Nicaise and Schinder in [11], based on the motivic volume, Nicaise and Ottem in [10] prove that the very general complete intersection of a cubic and a quadric in \(\mathbb {P}^6\) is stably irrational. However, it remained open if the very general (2, 3) complete intersection is retract rational or admits a decomposition of the diagonal. In contrast, all other complete intersection fourfolds which are known to be not stably rational, are also known to be not retract rational.

In [10] stable irrationality of many other varieties was proven. The retract rationality of a different variety whose stable irrationality was proven in [10] was studied in [12]. There Pavic and Schreieder prove retract irrationality of the quartic fivefold. To achieve this, Pavic and Schreieder use a more subtle specialization technique than the one used in this paper.

The main idea we will use is to find a (2,3)-complete intersection defined over \(\mathbb {Q}\), and specialize to a (2,3)-complete intersection defined over positive characteristic, which does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal.

Additionally, the example we find will give rise to an example in positive characteristic of a (2, 3)-complete intersection fourfold that is not retract rational. The fact that the examples are given by simple explicit equations is also a nice complement to Nicaise and Ottem’s results, which concern the very general complete intersection and therefore does not give examples defined over \(\mathbb {Q}\).

In this paper, we will prove the following results:

Theorem 1.1

Let \(K=\mathbb {Q}\) or \(K=\mathbb {F}_p(t)\) with \(p \ge 3\). In the first case let \(p \ge 3\), \(q \ge 11\) be distinct primes and set \(u=p,v=q\), and in the second case let \(u=t,v=(t-1)\). Let \(X \subset \mathbb {P}^6_K\) be the complete intersection defined by the following two equations:

Then X is a smooth complete intersection such that the base change to \({\overline{K}}\) does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal. It is therefore not geometrically retract rational.

The unifying property of the two choices for K is that varieties over K can be specialized to varieties over \(\mathbb {F}_p\). Using specialization techniques to prove irrationality of varieties defined over such fields goes back to [8], and was used together with the decomposition of the diagonal in [14, 18]

The structure of the paper is as follows: In Sect. 2 we collect the important definitions and results we will use to prove Theorem 1.1. Then in Sect. 3 we will prove that the complete intersection in Theorem 1.1 does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal. To do this we specialize the complete intersection to the union of two components, such that one component is birational to the quadric bundle found in [7], which does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal. This is the same specialization as the one used in [10].

2 Rationality and specialization

2.1 Unramified cohomology

Unramified cohomology groups of a variety are subgroups of the étale cohomology groups of the function field. If X is a scheme and F a sheaf on the small étale site on X, we denote the i-th étale cohomology group by \(H^i(X,F)\). If R is a ring we will use \(H^i(R,F)\) as a shorthand for \(H^i({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R,F)\).

We refer to [16] for an introduction to unramified cohomology. Following [9, 16], we define unramified cohomology using only geometric valuations. For a positive integer m invertible in the field k, we write \(\mu _m\) for the sheaf of m-th roots of unity.

Definition 2.1

[16, Definition 4.1] Let K/k be a finitely generated field extension. A geometric valuation \(\nu \) on K over k is a discrete valuation on K over k such that the transcendence degree of \(\kappa _\nu \), the residue field of the corresponding DVR, over k is given by

Definition 2.2

[16, Definition 4.3] Let K/k be a finitely generated field extension and let m be a positive integer that is invertible in k. We define the unramified cohomology of K over k with coefficients in \(\mu _m^{\otimes j}\) as the subgroup

consisting of all elements \(\alpha \in H^i(K,\mu _m^{\otimes j})\) such that \(\partial _\nu (\alpha ) = 0\) for any geometric valuation \(\nu \) on K over k.

Unramified cohomology has the following functoriality properties.

Proposition 2.3

[16, Proposition 4.7] Let \(K'/K/k\) be finitely generated field extensions, let \(f :{{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}K' \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}K\) be the natural morphism and let m be an integer that is invertible in k.

-

(i)

Then \(f^* :H^i(K,\mu _m^{\otimes j}) \rightarrow H^i(K',\mu _m^{\otimes j})\) induces a pullback map

$$\begin{aligned} f^* :H_{nr}^i\big (K/k,\mu _m^{\otimes j}\big ) \rightarrow H_{nr}^i\big (K'/k,\mu _m^{\otimes j}\big ) \end{aligned}$$ -

(ii)

If f is finite, then \(f_* :H^i(K',\mu _m^{\otimes j}) \rightarrow H^i(K,\mu _m^{\otimes j})\) induces a pushforward map

$$\begin{aligned} f_* :H_{nr}^i\big (K'/k,\mu _m^{\otimes j}\big ) \rightarrow H_{nr}^i\big (K/k,\mu _m^{\otimes j}\big ) \end{aligned}$$with \(f_* \circ f^* = deg(f) \cdot {{\,\mathrm{id}\,}}\)

We can aslo define the restriction of an unramified cohomology class.

Proposition 2.4

[16, Proposition 4.8] Let X be a smooth variety over a field k and let m be a positive integer that is invertible in k. Let \(\alpha \in H_{nr}^i(k(X)/k, \mu _m^{\otimes j})\).

-

(i)

Let \(x \in X\) be any scheme point. Then there is a well-defined restriction

-

(ii)

If X is also proper over k, then

is unramified over k.

is unramified over k.

2.2 The Merkurjev pairing

Following [14], we will use the Merkurjev pairing introduced in [9, Section 2.4] to detect whether a smooth variety has a decomposition of the diagonal.

Proposition 2.5

Let X be a smooth proper variety over a field K (not necessarily algebraically closed) and let m be an integer invertible in K. Then there is a bilinear pairing:

which we will write as \((z,\alpha ) \rightarrow \langle z,\alpha \rangle \). For a closed point z the pairing is given by:

for \(f_z :{{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}\kappa (z) \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}K\) the structure morphism.

2.3 Alterations

The Merkurjev pairing is defined on smooth varieties, and since resolution of singularities is still unknown in positive characteristic we will need to use alterations:

Let Y be a variety over an algebraically closed field k. An alteration of Y is a proper generically finite surjective morphism \(Y' \rightarrow Y\), where \(Y'\) is a regular variety over k. By de Jong [6], alterations exist in any characteristic and by work of Gabber the degree of the alteration can be chosen to be coprime to any prime not dividing the characteristic of the field. In fact Temkin proves that one can choose the degree to be a power of the characteristic [17, Theorem 1.2.5] (or degree 1 if \({{\,\mathrm{char}\,}}(k)=0\)).

2.4 Decomposition of the diagonal

The decomposition of the diagonal technique was introduced in [2], and its use in answering questions of retract rationality was developed by among others [4, 14, 15, 18, 19].

Definition 2.6

We say a scheme of pure dimension n over a field k admits a decomposition of the diagonal if we have an equality:

where \(Z_X\) is a cycle supported on \(D \times X\) for some divisor \(D \subset X\) and \(z \in Z_0(X)\) is a zero-cycle on X.

There is a natural isomorphism

Where we write \(X_{k(X)}\) for the base change of X to its function field k(X). Using this, we can also think of a decomposition of the diagonal as an equality:

where we write \(\delta _X\) for the zero-cycle on \(X_{k(X)}\) induced by the diagonal.

The following lemma relates decompositions of the diagonal to retract rationality:

Lemma 2.7

(See, e.g., [14, Lemma 2.4]) A variety X over a field k that is retract rational admits a decomposition of the diagonal.

2.5 The specialization method

The following result is the key ingredient in using specialization to prove that a variety is not retract rational.

Proposition 2.8

[16, Corollary 8.3] Let R be a discrete valuation ring with fraction field K and algebraically closed residue field k. Let \(\pi :{\mathscr {X}} \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R\) be a proper flat R-scheme with connected fibers and denote by \(X = {\mathscr {X}} \times {\overline{K}}\) and \(Y = {\mathscr {X}} \times k\) the geometric generic fiber and geometric special fiber of \(\pi \). Assume that X admits a decomposition of the diagonal and the special fiber Y is pure-dimensional, then Y admits a decomposition of the diagonal as well.

3 A non-retract rational (2,3)-complete intersection

We will apply the specialization technique to find a quadric and a cubic fivefold, defined over \(\mathbb {Q}\), such that their intersection is a smooth non-retract rational variety. Using the specialization from [10], the complete intersection specializes to a variety birational to the variety constructed in [7], which has a non-trivial unramified cohomology class. From this it will follow that the original complete intersection is not retract rational.

Let \(R = \mathbb {Z}\) or \(R=\mathbb {F}_p[t]\) for \(p \ge 3\), with field of fractions K. If \(R=\mathbb {Z}\) we pick any two distinct primes \(p \ge 3\), \(q \ge 11\) and set \(u=p,v=q\), in the other case we set \(u=t,v=(t-1)\). We will consider the complete intersection \({\mathscr {X}} {:}{=} {\mathscr {Q}} \cap {\mathscr {C}} \subset \mathbb {P}_{R}^6\), where \({\mathscr {Q}}\) and \({\mathscr {C}}\) are the following hypersurfaces:

Lemma 3.1

Let \({\mathscr {X}}\) be as above and let X be the generic fiber of \({\mathscr {X}} \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R\), then X is a smooth complete intersection in \(\mathbb {P}_{K}^6\).

Proof

Consider the scheme \({\mathscr {X}} \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R\). If \(R=\mathbb {Z}\), the fiber over (q) is the intersection of the Fermat quartic and the Fermat cubic in \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_q }^6\), which is smooth. If \(R=\mathbb {F}_p[t]\) we look at the fiber over the ideal \((t-1)\) and apply the same argument. \(\square \)

Remark 3.2

The assumption that the prime \(q \ge 11\) is to ensure that the intersection of the Fermat quadric and Fermat cubic is smooth in characteristic q.

Let \({\mathfrak {p}}\) be the ideal (p) or (t) depending on if R is \(\mathbb {Z}\) or \(\mathbb {F}_p[t]\) respectively. Let \({\mathscr {X}} \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R_{{\mathfrak {p}}}\) be defined by the two equations (3) and (4). The fiber \(X_p\) above the closed point \({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}\mathbb {F}_p\) is the complete intersection in \(\mathbb {P}^6_{\mathbb {F}_p}\) of the two hypersurfaces:

We will prove that the base change of \(X_p\) to \(\overline{\mathbb {F}_p}\) does not have a decomposition of the diagonal. Then, from Proposition 2.8, it will follow that X is not geometrically retract rational over \({\overline{\mathbb {Q}}}\).

The hypersurface \(Q_p\) is the cone over a quadric surface \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\) embedded in the \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^3 \subset \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^6\) that has coordinates \(x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6\). It is singular along the plane \(V(x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6)\), which is the vertex of the cone.

The complete intersection \(X_p = Q_p \cap C_p\) is also singular along the plane \(V(x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6)\). Additionally, one can compute that it is singular along four curves: The plane conics defined by

and the plane cubics defined by:

To check that \(X_p\) does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal, we will construct a less singular birational model \(X_1\).

It is straightforward to check the following:

Lemma 3.3

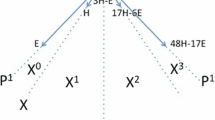

The blow-up of \(Q_p\) in the vertex plane \(V(x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6)\) is a map

defined by the base-point-free linear system \(|\mathscr {O}_P(1)|\).

We fix \(\{ U,V,W,y_0z_0T,y_0z_1T,y_1z_0T,y_1z_1T \}\) as the basis of \(H^0(\mathscr {O}_P(1))\) that induces \(\rho \), where \(y_i\) and \(z_i\) are coordinate functions on \(\mathbb {P}^1 \times \mathbb {P}^1\).

Let F be the following polynomial

which we regard as a section of \(|\mathscr {O}_P(2) \otimes p^*(\mathscr {O}_{\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1}(1,1))|\).

Lemma 3.4

With notation as above, the strict transform \(X_1\) of \(X_p\) in P is defined by \(F(y_0,y_1,z_0,z_1,U,V,W,T) = 0\). Furthermore, the exceptional divisor E of the restriction of \(\rho \) to \(X_1\), \(\rho _{X_1} :X_1 \rightarrow X_p\) is defined by \(F(y_0,y_1,z_0,z_1,U,V,W,T) = T = 0\).

Proof

A straightforward computation shows that \(\rho ^{-1}(X_p)\) is defined by

which we recognize as having two components. The component defined by \(T=0\) is the exceptional divisor and the other component is the strict transform of \(X_p\). \(\square \)

To apply the specialization method in Proposition 2.8 with special fiber \(X_p\), we must prove that the geometric special fiber \({\overline{X}}_p\) does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal. We will prove this by studying \(X_1\). Following the method developed in [14], the first step is to check that the singular locus of \(X_1\) does not dominate \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\), and that the exceptional divisor meets the smooth locus.

Lemma 3.5

The generic fiber of the map \(f :X_1 \rightarrow \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\) is smooth and meets E. Furthermore, the generic fiber of \(f_E :E \rightarrow \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\) is also smooth.

Proof

Let K be the field corresponding to the generic point of \(\mathbb {P}^1 \times \mathbb {P}^1\). Then the generic fiber of f is a quadric surface over K defined by the polynomial F, as a polynomial in K[U, V, W, T]. Since this quadric is in diagonal form with non-zero coefficients, it is smooth. Furthermore, since the subvariety E is defined by \(T=0\), it must meet the generic fiber of f and dominate \(\mathbb {P}^1 \times \mathbb {P}^1\). The second statement is proven in the same manner as the first. \(\square \)

Remark 3.6

More precisely, the variety \(X_1\) is singular along six curves, two curves projecting to points in \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\), two curves not contained in E that project to coordinate axes in \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\) and two curves contained in E that project to coordinate axes in \(\mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1 \times \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^1\). These three pairs of curves are defined by

and

respectively. Furthermore, E is singular along the two curves defined by (10).

In the remainder of this section, we will consider \({\overline{X}}_1 {:}{=} X_1 \otimes \overline{\mathbb {F}_p}\), the base change of \(X_1\) to the algebraic closure of \(\mathbb {F}_p\). We will first look at the unramified cohomology of \({\overline{X}}_1\) and then use this to obstruct the existence of a decomposition of the diagonal.

In [7], Hassett, Pirutka and Tschinkel describe the following quadric surface bundle over \(\mathbb {P}^2\), which has a non-trivial class in unramified cohomology.

Proposition 3.7

c.f. [7, Proposition 10] Let \(k=\mathbb {C}\) [7] or let k be an algebraically closed field of characteristic different from 2 [16], let \(\mathbb {P}_k^2 \times \mathbb {P}_k^3\) have coordinates x, y, z and s, t, u, v respectively. Let \(K = k(x,y) = k(\mathbb {P}_k^2)\), and \(f :Y \rightarrow \mathbb {P}_k^2\) be the hypersurface defined by:

where

Then Y is a quadric surface bundle over \(\mathbb {P}_k^2\) with a non-trivial unramified cohomology class

In [7], the authors work over \(\mathbb {C}\), but in [16, Proposition 9.6] it is observed that the same proof works as long as k is an algebraically closed field of characteristic different from 2. An immediate consequence is:

Corollary 3.8

With notation as above, \({\overline{X}}_1\) is birational to the quadric surface bundle Y defined in Proposition 3.7. It follows that there is a non-trivial class \(0 \ne \alpha = f^*((\frac{y_1}{y_0},\frac{z_1}{z_0})) \in H_{nr}^2(k(X_1)/k,\mu _2^{\otimes 2})\)

Proof

The ambient spaces of Y and \({\overline{X}}_1\) are birational, and are isomorphic on the open sets defined by \(z \ne 0\) and \(y_0,z_0 \ne 0\) respectively. If we set \(z=1\) in the defining equation of Y, and \(y_0=z_0=1\) in the defining equation for \(X_1\), the equations are equal. So the birational map on the ambient spaces induces a birational map between Y and \({\overline{X}}_1\). Therefore, \(k(Y) \simeq k(X_1)\), so the corresponding unramified cohomology groups are also isomorphic. \(\square \)

Using the explicit description of the non-zero class \(\alpha \), we obtain the following result.

Lemma 3.9

Let \({\overline{E}} \subset {\overline{X}}_1\) be the exceptional divisor. Consider the class \(\alpha = f^*((\frac{y_1}{y_0},\frac{z_1}{z_0})) \in H_{nr}^2(k({\overline{X}}_1)/k,\mu _2^{\otimes 2})\). Then \(\alpha \) restricted to the smooth locus \({\overline{E}}^\circ \) of \({\overline{E}}\) is zero.

Proof

The unramified cohomology groups \(H_{nr}^2(k({\overline{X}}_1)/k,\mu _2^{\otimes 2})\) and \(H_{nr}^2(k({\overline{E}})/k,\mu _2^{\otimes 2})\) are isomorphic to the 2-torsion in the Brauer groups, written \({{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{X}}_1))[2]\) and \({{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{E}})))[2]\) respectively (c.f. [16, Proposition 4.11]). Furthermore, the isomorphism is compatible with the restriction maps. Using the affine coordinates \(y_1\) and \(z_1\) the non-zero class \(\alpha \in {{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{X}}_1))[2]\) corresponds to the conic

which has no points over \(k({\overline{X}}_1)\). The restriction of \(\alpha \) to \({{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{E}})))[2]\) corresponds to the same quadric over the field \(k({\overline{E}})\). However, in \(k({\overline{E}})\) we have the relation \(z_1U^2 + y_1V^2 + y_1z_1W^2 = 0\), so for any square root \(\iota \) of \(-1\), the conic

has a point over \(k({\overline{E}})\) given by \(A=V,B=U,C=\iota W\). Therefore, the restriction of \(\alpha \) to \({{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{E}})))[2]\) is trivial. The conclusion then follows from functoriality and the fact that \({{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({\overline{E}}^\circ ) \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Br}\,}}({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(k({\overline{E}})))\) is injective [5, Theorem 3.5.5]. \(\square \)

Remark 3.10

The subvariety E is rational, but because it is singular it does not follow immediately that the restriction of \(\alpha \) to any scheme point in E vanishes.

While \(X_1\) is still singular, the following result by Schreieder will ensure that the singularities of \(X_1\) do not interfere with the Merkurjev pairing.

Theorem 3.11

[16, Theorem 10.1] Let \(f :Y \rightarrow S\) be a surjective morphism of proper varieties over an algebraically closed field k with \(char(k) \ne 2\) whose generic fiber is birational to a smooth quadric over k(S). Let \(n = \dim (S)\) and assume that there is a class \(\alpha \in H^n(k(S),\mu _2^{\otimes n})\) with \(f^* \alpha \in H_{nr}^n(k(Y)/k,\mu _2^{\otimes n})\). Then for any dominant generically finite morphism \(\tau :Y' \rightarrow Y\) of varieties and for any subvariety \(E \subset Y'\) that meets the smooth locus of \(Y'\) and which does not dominate S via \(f \circ \tau \), we have  .

.

We are now ready to prove that the geometric special fiber does not have a decomposition of the diagonal. The proof strategy is the same as in [14, Proposition 3.1].

Proposition 3.12

Let \(X_p\) be the complete intersection \(Q_p \cap C_p \subset \mathbb {P}_{\mathbb {F}_p}^6\) from (5) and (6) and let \({\overline{X}}_p\) be the base change of \(X_p\) to \(k {:}{=} \overline{\mathbb {F}_p}\), the algebraic closure of \(\mathbb {F}_p\). Then \({\overline{X}}_p\) does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal.

Proof

Assume for contradiction that

is a decomposition of the diagonal of \({\overline{X}}_p\), where z is a zero-cycle on \({\overline{X}}_p\) The map \(\rho _{X_1} :{\overline{X}}_1 \rightarrow {\overline{X}}_p\) (cf. Lemma 3.4) is the blow-up of \({\overline{X}}_p\) in a plane, and therefore an isomorphism on the complement of the exceptional divisor \({\overline{E}}\). Hence, \(\rho _{X_1}^*(\delta _{{\overline{X}}_p}) = \delta _{{\overline{X}}_1}\). Using this and the exact sequence:

we get the following equality, where we write K for \(k({\overline{X}}_1)\).

for some zero-cycle \(z'\) supported on \({\overline{E}}\).

Let \(\tau :{\widetilde{X}}_1 \rightarrow {\overline{X}}_1\) be an alteration of odd degree, and let \(U \subset {\overline{X}}_1\) be a subset of the smooth locus of \({\overline{X}}_1\) such that \(U \cap {\overline{E}}\) is smooth and the complement \(X_1 {\setminus } U\) does not dominate \(\mathbb {P}^1 \times \mathbb {P}^1\). In fact, from Remark 3.6, one can simply let U be the smooth locus of \(X_1\). Define \({\widetilde{U}} \,{:}{=}\, \tau ^{-1}(U)\) and consider the following commutative diagram:

Since j is flat and both \({\widetilde{U}}_{K}\) and \(U_{K}\) are smooth, there are well-defined pullback maps \(j^*\) and \(\tau _{{\widetilde{U}}}^*\) on Chow rings. Pulling back (11) by \(\tau _{{\widetilde{U}}}^* \circ j^*\) gives an equality

Since \(\tau \) is étale in a neighborhood of the diagonal point, we have \(\tau _{{\widetilde{U}}}^*(j^* \delta _{{\overline{X}}_1}) = {\widetilde{\delta }}_{\tau }\), where \({\widetilde{\delta }}_\tau \) is the 0-cycle corresponding to the graph of the map \(\tau \) in \({\widetilde{X}}_1 \times X_1\).

In \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_0(({\widetilde{X}}_1)_K)\) we get the equality:

where \([z_{K}]\) is supported on \({\widetilde{U}}_{K}\), \([{\widetilde{z}}'_{K}]\) is supported on \(\tau ^{-1}(U_{K} \cap {\overline{E}}_{K})\) and \([z''_{K}])\) on \({\widetilde{X}}_1 {\setminus } {\widetilde{U}}\).

We will compute the pairing of each term in (13) with the class \(\tau ^* \alpha \) to obtain a contradiction. To compute the pairing of \({\widetilde{\delta }}_{\tau }\) with \(\tau ^*\), recall that \({\widetilde{\delta }}_{\tau }\) represents the graph of \(\tau \). Since this graph is isomorphic to \({\widetilde{X}}_1\), \(\tau \) induces a map from \(k({\widetilde{X}}_1)\), the residue field of \({\widetilde{\delta }}_{\tau }\), to \({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}(K)\). Furthermore, to compute the pairing, we compute the pushforward of \(\tau ^* \alpha \) by this map. Therefore we have:

The class is non-zero since \(\alpha \) is non-zero of even order.

We now compute the pairing of \(\tau ^* \alpha \) with the summands on the right-hand side. Firstly,

since the pairing factors through the restriction of \(\tau ^*\alpha \) to a closed point on \({\widetilde{X}}_1\), a smooth variety over an algebraically closed field, and the restriction of unramified cohomology classes of positive degree to such classes vanishes.

Secondly,

since the restriction of \(\tau ^* \alpha \) to \({\widetilde{z}}\) factors through the restriction of \(\tau ^* \alpha \) to \(\tau ^{-1}(U_{K} \cap {\overline{E}}_{K})\). By functoriality, this restriction is equal to \(\tau ^*(i^* \alpha )\), where \(i :U_{K} \cap {\overline{E}}_{K} \rightarrow ({\overline{X}}_1)_{K}\) is the inclusion map. From Lemma 3.9 we know that \(i^* \alpha \) vanishes, so \(\langle [{\widetilde{z}}'_{K}],\tau ^*\alpha , = \rangle 0\).

Finally, by Theorem 3.11,

since by Lemma 3.5 the singular locus of \(X_1\) does not dominate \(\mathbb {P}^1 \times \mathbb {P}^1\).

From these computations, we see that the pairing of \(\tau ^*\alpha \) with the left hand side of (13) is non-zero, but the pairing of \(\tau ^*\alpha \) with the right-hand side of (13) is zero. This contradiction proves that \({\overline{X}}_p\) cannot have a decomposition of the diagonal. \(\square \)

using this we can apply Proposition 2.8 to get the main result of the paper:

Theorem 3.13

Let \(R=\mathbb {Z}\) or \(R=\mathbb {F}_p[t]\) with field of fractions K. In the first case let \(p \ge 3, q \ge 11\) be distinct primes and set \(u=p, v=q\), and in the second case let \(u=t,v=(t-1)\). Let \(X_1\) be the smooth complete intersection in \(\mathbb {P}^6_{K}\) defined by the intersection \(Q \cap C\) for

Then \(X_1\) is not geometrically retract rational.

Proof

After a base change \({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R' \rightarrow {{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R_{(u)}\) we can assume that \(X_1\) is defined over a DVR with residue field \(\overline{\mathbb {F}_p}\). Then, by Lemma 3.12, the special fiber does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal. From Proposition 2.8, we can then conclude that the geometric generic fiber over \({{\,\mathrm{Spec}\,}}R'\) does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal, and is therefore not geometrically retract rational. Since this geometric generic fiber is a base change of \(X_1\), it follows that \(X_1\) is also not geometrically retract rational. \(\square \)

Remark 3.14

By a specialization argument, it follows from the existence of a single smooth (2, 3) complete intersection that does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal, that the very general such intersection does not admit a decomposition of the diagonal and is therefore not retract rational. Since in this case the special fiber is smooth, one can in this case also use the specialization technique from [4, Theorem 1.12] to prove that the very general fiber has no decomposition of the diagonal.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Braune, L.: Irrational complete intersections (2019). arXiv: 1909.05723 [math.AG]

Bloch, S., Srinivas, V.: Remarks on correspondences and algebraic cycles. Am. J. Math. 105(5), 1235–1253 (1983). https://doi.org/10.2307/2374341. ISSN: 0002-9327

Chatzistamatiou, A., Levine, M.: Torsion orders of complete intersections. Algebra Number Theory 11(8), 1779–1835 (2017). https://doi.org/10.2140/ant.2017.11.1779. ISSN: 1937-0652

Colliot-Théléne, J.-L., Pirutka, A.: Hypersurfaces quartiques de dimension 3: non-rationalité stable (4). Ann. Sci. Éc. Norm. Supér 49(2), 371–397 (2016). https://doi.org/10.24033/asens.2285. ISSN: 0012-9593

Colliot-Théléne, J.-L., Skorobogatov, A.N.:The Brauer–Grothendieck group. Vol. 71. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete. 3. Folge. A Series of Modern Surveys in Mathematics [Results in Mathematics and Related Areas. 3rd Series. A Series of Modern Surveys in Mathematics]. Springer, pp. xv+453. ISBN: 978-3-030-74247-8 (2021)

de Jong, A.J.: Smoothness, semi-stability and alterations. Inst. Hautes Études Sci. Publ. Math. 83, 51–93 (1996). ISSN: 0073-8301

Hassett, B., Pirutka, A., Tschinkel, Y.: Stable rationality of quadric surface bundles over surfaces. Acta Math. 220(2), 341–365 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4310/ACTA.2018.v220.n2.a4. ISSN: 0001-5962

Kollár, J.: Nonrational hypersurfaces. J. Am. Math. Soc. 8(1), 241–249 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2307/2152888. ISSN: 0894-0347

Merkurjev, A.: Unramified elements in cycle modules. J. Lond. Math. Soc 78.1(2), 51–64 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1112/jlms/jdn011. ISSN: 0024-6107

Nicaise, J., Ottem, J.C.: Tropical degenerations and stable rationality (2020). arXiv: 1911.06138 [math.AG]

Nicaise, J., Shinder, E.: The motivic nearby fiber and degeneration of stable rationality. Invent. Math. 217(2), 377–413 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00222-019-00869-2. ISSN: 0020-9910

Pavic, N., Schreieder, S.: The diagonal of quartic fivefolds (2021). arXiv: 2106.04539 [math.AG]

Schreieder, S.: On the rationality problem for quadric bundles. Duke Math. J. 168(2), 187–223 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1215/00127094-2018-0041. ISSN: 0012-7094

Schreieder, S.: Stably irrational hypersurfaces of small slopes. J. Am. Math. Soc 32(4), 1171–1199 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1090/jams/928. ISSN: 0894-0347

Schreieder, S.: Torsion orders of Fano hypersurfaces. Algebra Number Theory 15(1), 241–270 (2021). https://doi.org/10.2140/ant.2021.15.241. ISSN: 1937-0652

Schreieder, S.: Unramified cohomology, algebraic cycles and rationality. In: Rationality of Varieties, pp. 345–388. Springer (2021)

Temkin, M.: Tame distillation and desingularization by p-alterations. Ann. Math. 186.1(2), 97–126 (2017). https://doi.org/10.4007/annals.2017.186.1.3. ISSN: 0003-486X

Totaro, B.: Hypersurfaces that are not stably rational. J. Am. Math. Soc. 29(3), 883–891 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1090/jams/840. ISSN: 0894-0347

Voisin, C.: Unirational threefolds with no universal codimension 2 cycle. Invent. Math. 201(1), 207–237 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00222-014-0551-y. ISSN: 0020-9910

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my advisor John Christian Ottem for suggesting the topic, and for helpful advice throughout the writing process. I also wish to thank Stefan Schreieder for an enlightening conversation at the Mittag-Leffler institute. This material is partly based upon work supported by the Swedish Research Council under grant no. 2016-06596 while the author was in residence at Institut Mittag-Leffler in Djursholm, Sweden during the fall of 2021. I am also indebted to the referee for their careful reading and suggestions for improving the paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skauli, B. A (2,3)-complete intersection fourfold with no decomposition of the diagonal. manuscripta math. 171, 473–486 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00229-022-01386-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00229-022-01386-y

is unramified over k.

is unramified over k.