Abstract

Purpose

To perform a systematic umbrella review with meta-analysis to evaluate the certainty of evidence on mortality risk associated with digoxin use in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with or without heart failure (HF).

Methods

We systematically searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception to 19 October 2021. We included systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies investigating digoxin effects on mortality of adult patients with AF and/or HF. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality; secondary outcome was cardiovascular mortality. Certainty of evidence was evaluated by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool and the quality of systematic reviews/meta-analyses by the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR2) tool.

Results

Eleven studies accounting for 12 meta-analyses were included with a total of 4,586,515 patients. AMSTAR2 analysis showed a high quality in 1, moderate in 5, low in 2, and critically low in 3 studies. Digoxin was associated with an increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.19, 95% confidence interval [95%CI] 1.14–1.25) with moderate certainty of evidence and with an increased cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.19, 95%CI 1.06–1.33) with moderate certainty of evidence. Subgroup analysis showed that digoxin was associated with all-cause mortality both in patients with AF alone (HR 1.23, 95%CI 1.19–1.28) and in those with AF and HF (HR 1.14, 95%CI 1.12–1.16).

Conclusion

Data from this umbrella review suggests that digoxin use is associated with a moderate increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in AF patients regardless of the presence of HF.

Trial registration

This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022325321).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The management of patients suffering from atrial fibrillation (AF) is multifactorial including thromboprophylaxis for cardioembolic stroke by anticoagulant treatment, symptoms management, and rate and rhythm control by anti-arrhythmic drugs [1, 2]. Indeed, beyond anticoagulation therapy, rhythm and rate control strategies are cornerstone for the acute and chronic management of patients with AF [3]. Among anti-arrhythmic drugs, digoxin is a still widely used drug to control heart rate in AF patients. The 2020 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend beta-blockers and/or digoxin to control heart rate in AF patients with left ventricular ejection fraction < 40% (class I level of evidence B) [3]. In addition, the ESC guidelines recommend the long-term use of digoxin in patients in whom an adequate rate control cannot be achieved by beta blockers at maximum tolerated dose or when beta-blockers are contraindicated or not tolerated with low class of evidence (IIa) [3].

Digoxin is also recommended by the “2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure” for the treatment of patients with heart failure (HF) and sinus rhythm to reduce the risk of hospitalization and symptoms burden (class IIb level B) [4]. A similar recommendation is provided by the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure [5].

During the last decades, concerns regarding the safety of digoxin have been raised. In particular, some studies showed an increased risk of death in patients with AF treated with digoxin, especially when supratherapeutic blood concentrations are reached [6, 7]. Given the possibility of the presence of an indication bias (i.e., administration of digoxin to sicker patients), also propensity-matched studies have been performed providing divergent conclusions [8, 9].

However, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses investigating the association of digoxin with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality reported conflicting evidence [10, 11].

Given the impossibility of obtaining data from a randomized trial testing the safety and efficacy of digoxin in addition to standard therapy, we performed an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, focusing on patients with AF with and without HF, in whom the use of digoxin has recommendation by international guidelines.

Methods

This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022325321). This umbrella review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Data sources and searches

A systematic literature search was conducted by two independent authors on MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception to 19 October 2021. Keywords used to perform the search were “digoxin”, “atrial fibrillation”, “mortality”, and “meta-analysis” combined with Boolean operators were used to find articles. Search strategy was adapted for each database; a complete list of search strings is available in Supplementary Material 1.

Study selection

Criteria of inclusion were defined as follows: Meta-analysis of studies investigating digoxin effects compared to standard of care on mortality of patients with AF; patients included in studies must be at least 18 years old; effect sizes must be provided as relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Only articles with full-text available were considered. No restrictions were placed on language or publication date. Meta-analyses which did not report data concerning mortality were excluded. Multiple meta-analyses reported in a single paper (e.g., multiple outcomes or based on different types of studies) were included separately.

Study selection was performed by two independent authors, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with the senior author. Titles and abstracts of each article were screened to remove duplicates, and full texts of promising articles were read to assess eligibility. Reference lists of eligible articles were hand-searched to identify additional relevant meta-analyses.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted the following data from each eligible study: name of first author; year of publication; outcomes; databases whose searches were based on; period of time searched; number and type of included studies; follow-up period; digoxin indication; number of patients with AF; overall mortality; cardiovascular mortality; mortality in patients with only AF; and mortality in patients with AF and HF.

Outcomes

All-cause mortality was the primary outcome. Secondary endpoint was cardiovascular mortality. A subgroup analysis in patients with AF alone or AF and HF was performed.

Quality evaluation and risk of bias assessment

Quality of each included meta-analysis was evaluated with the assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR) 2 tool [13]. This tool aims at evaluating systematic reviews quality by answering “no”, “partial yes”, or “yes” to 16 different items. Items 4, 9, 11, 12, and 15 are considered critical domains. The quality of studies was defined as follows: high (no or 1 non-critical weakness), moderate (more than 1 non-critical weakness), low (1 critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses), or critically low (more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses) (Table 1).

Data synthesis and analysis

Meta-analyses for each endpoint separately were performed based on random effects, using the logarithm of hazard ratios (HRs) associated as outcome. Inverse variance weights were used in all cases. Pooled effects were obtained through maximum likelihood.

Heterogeneity was evaluated by calculating the I2 index. According to arbitrary cut-offs, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity was defined as an I2 of < 25%, 25–75%, and > 75%, respectively.

Publication bias was assessed for studies reporting outcomes according to digoxin use, with the use of funnel plots. Egger’s test was also performed.

Analyses were performed using the R (R Development Core Team) software version 3.6.1; statistical significance level was set at 0.05, and all p values were two-tailed.

Certainty of evidence

Two authors independently evaluated certainty of evidence using GRADEproGDT according to the GRADE Handbook [14]. GRADE categorizes certainty of evidence into very low, low, moderate, or high; the higher the category, the greater the confidence that the true effect is close to the reported findings. The following characteristics are considered in order to assess the right category: design of study (observational, randomized clinical trial), inconsistency across studies (I2 statistics), imprecision of the findings, indirectness (e.g., due to mixed outcome), publication bias, size effect, and presence of dose–response gradient.

Ethics approval

This is an umbrella review with meta-analysis. No ethical approval is required.

Results

Three hundred ninety-seven articles were obtained from the initial search. After duplicates removal, 350 papers were evaluated. After a first screening, 39 studies were eligible for detailed analysis, but 5 had no full-text available. Finally, 11 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the umbrella review. The strategy search is summarized in PRISMA flow diagram (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1 shows AMSTAR 2 items evaluation for every included meta-analysis. Overall, out of the 11 papers, 1 had a high, 5 moderate, 2 low, and 3 critically low quality. In particular, as far as it regards critical domains, each paper reported a proper use of comprehensive literature search queries and a significant publication bias assessment (Q4, 11/11, and Q15, 11/11, respectively). Almost every paper used an appropriate method for statistical combination of the results (Q11, 10/11), while some critical issues were found in the evaluation of technique for assessing risk of bias and in determining its implication on the results of the meta-analysis (Q9 8/11 and Q12 6/11, respectively).

Strategy search, year of publication, inclusion, and exclusion criteria are reported in Table 2.

Table 3 summarizes meta-analysis characteristics. Each study reported synthesis of results expressed as HR or RR. One paper (Sethi et al.) included only RCTs, while the others included observational studies and data from registries as well. A total of 4,586,515 patients were included. The length of follow-up ranged from 0.4 to 4.7 years. Notably, Ziff and colleagues [11] reported data on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality separately for observational and interventional studies; given the different populations in the two analyses, we considered them as two different studies.

Funnel plots reported in the Supplementary Fig. 2 did not show significant publication bias.

All-cause and cardiovascular mortality

All the included studies reported data on the primary outcome, the all-cause mortality. Figure 1 shows the results of our umbrella review concerning mortality. Digoxin was associated with an increased mortality in the overall population (HR 1.19, 95%CI 1.14–1.25, panel A) with moderate certainty of evidence according to the GRADE (Table 4) and moderate-high heterogeneity (I2 75.8%).

Data on cardiovascular mortality were provided by 5 studies (Fig. 2). Overall, the evidence suggests that digoxin might result in an increase in cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.19, 95%CI 1.06–1.33) with moderate certainty of evidence according to the GRADE (Table 4) and moderate heterogeneity (I2 70.5%).

Subgroup analysis according to the HF

As far as it concerns mortality in AF-only population (Fig. 1B), only 8 papers provided data concerning this outcome. Our analysis shows that digoxin may result in an increase in mortality in this group of patients (HR 1.23, 95%CI 1.19–1.28) with low certainty of evidence according to the GRADE (Table 4) and moderate heterogeneity (I2 70.8%).

Mortality in patients affected by AF and HF outcome (Fig. 1C) was explored by 8 papers and provided similar results. Even in this population, digoxin was associated with an increase in mortality (HR 1.14, 95%CI 1.12–1.16) with moderate certainty of evidence according to the GRADE (Table 4) and no heterogeneity (I2 0%).

Discussion

Results from this umbrella review of meta-analyses indicate that the use of digoxin may be associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with AF.

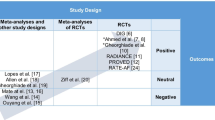

The need for this umbrella review and meta-analysis came from literature analysis in which a growing number of observational studies reported a potential harmful effect of digoxin in AF patients [15, 16]. However, this evidence became conflicting after the publication of some meta-analyses providing discordant results. For this reason, we adopted the methodology of the umbrella review, which represents one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis currently available [17], to provide more robust data on the association between digoxin and mortality in patients with AF, given the lack of data from a controlled randomized setting. Our analysis indicates an association of digoxin use with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with AF.

Notably, the association with all-cause mortality persisted in the subgroup of patients with AF and HF, even if with a lower strength of association. The use of digoxin in AF patients with HF is well established in clinical practice, but it should be noted that consolidated evidence showed that the effect of digoxin may not be so evident when a stable haemodynamic has been already reached with other drugs such as diuretics and vasodilators [18], and that digoxin may work less when an activation of sympathetic system is present (e.g., acute decompensated HF) [19]. Thus, HF should not represent per se an indication to the use of digoxin as possible harmful effects are also evident in this subgroup of patients. One of the arguments for the still wide use of digoxin is its ability to reduce the rate of hospitalization and the improvement of symptoms in patients treated with this drug [20]. However, more recently, the TREAT-AF trial included patients with permanent AF and HF randomized to receive digoxin or bisoprolol [21]. This study showed no difference between the two treatments group regarding symptoms after 6 months of therapy [21].

Strengths of the study are that it is the first systematic umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses including a large sample of patients; even if a number of patients may be counted more than once given the design of umbrella review, it still remains the largest number of subjects considered to our knowledge. Furthermore, we also performed an accurate quality evaluation, certainty of evidence analysis, and risk of bias.

The different results obtained from the present umbrella review and meta-analysis in comparison to other previously published meta-analyses may rely on several reasons including different selection of studies, definition of outcomes variable length of follow-up, and lack of quality evaluation of evidence. In addition, 3 previous meta-analyses had critically low quality, and 2 had low quality at AMSTAR evaluation.

Clinical implications of our results are relevant considering that a high number of patients are currently treated with digoxin worldwide. Clinicians should be aware that digoxin may be harmful in AF patients, especially in some specific settings such as in chronic kidney disease or electrolyte imbalance, both conditions increasing the risk of adverse effects. In addition, patients prescribed on digoxin should be adequately informed about the potential side effects and the need of regular medical and laboratory follow-up while taking this medication.

Our results indicate that digoxin should be considered only in patients who do not achieve an adequate rate control or who experience symptoms with other anti-arrhythmic drugs. In addition, digoxin may be considered in patients with contraindication to the use of beta blockers (e.g., pulmonary disease) or to the use of calcium channel antagonists (such as heart failure). The use of laboratory monitoring and careful electrocardiographic examination may help recognize the early signs of digoxin toxicity, allowing a prompt intervention to reduce the risk of mortality associated with supra-therapeutic values of plasma digoxin. Indeed, values exceeding the therapeutic range may result in an increased risk of pro-thrombotic [22] and pro-arrhythmogenic effect and in an increased endothelial platelet activation [19, 22, 23], all mechanisms leading to an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.

There are limitations of this analysis to acknowledge. First, despite the umbrella review approach provides robust evidence regarding the association between digoxin and mortality, the inclusion of observational studies carries some intrinsic limitations, mainly due to the impossibility of eliminating the bias by indication, which implicates that patients prescribed on digoxin may be sicker than those not treated with this drug despite the multivariable adjustment for the most common comorbidities [24]. However, it should be noted that subgroup analysis of propensity-matched populations provided similar results [11]. However, what cannot be deduced from clinical studies is the reason for mortality, so we do not know if toxicity, arrhythmia, and HF were the causes of death. Indeed, data on serum digoxin concentration, renal function, acute coronary syndrome, potassium levels may provide important additional information to understand the association of digoxin with clinical outcomes. Furthermore, we do not know if patients were adequately followed after digoxin prescription.

In conclusion, despite its wide use, the use of digoxin should be considered with caution in patients with AF and should be reserved to those patients in whom an adequate rate control is difficult to achieve with other anti-arrhythmic drugs.

References

Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB, Kellen JC, Greene HL, Mickel MC, Dalquist JE, Corley SD, Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management I (2002) A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 347(23):1825–1833. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021328

Pastori D, Pignatelli P, Menichelli D, Violi F, Lip GYH (2019) Integrated care management of patients with atrial fibrillation and risk of cardiovascular events: the ABC (atrial fibrillation better care) pathway in the ATHERO-AF study cohort. Mayo Clin Proc 94(7):1261–1267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.022

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL, Group ESCSD (2020) 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Bohm M, Burri H, Butler J, Celutkiene J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A, Group ESCSD (2021) 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 42(36):3599–3726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR, Fang JC, Fedson SE, Fonarow GC, Hayek SS, Hernandez AF, Khazanie P, Kittleson MM, Lee CS, Link MS, Milano CA, Nnacheta LC, Sandhu AT, Stevenson LW, Vardeny O, Vest AR, Yancy CW (2022) 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 101161CIR0000000000001063. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

Lopes RD, Rordorf R, De Ferrari GM, Leonardi S, Thomas L, Wojdyla DM, Ridefelt P, Lawrence JH, De Caterina R, Vinereanu D, Hanna M, Flaker G, Al-Khatib SM, Hohnloser SH, Alexander JH, Granger CB, Wallentin L, Committees A, Investigators, (2018) Digoxin and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 71(10):1063–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.060

Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM (2003) Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Med Assoc 289(7):871–878

Freeman JV, Reynolds K, Fang M, Udaltsova N, Steimle A, Pomernacki NK, Borowsky LH, Harrison TN, Singer DE, Go AS (2015) Digoxin and risk of death in adults with atrial fibrillation: the ATRIA-CVRN study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 8(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002292

Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, van Veldhuisen DJ, Cleland JG, Butler J, Epstein AE, Patel K, Aban IB, Aronow WS, Anker SD, Ahmed A (2013) Lack of evidence of increased mortality among patients with atrial fibrillation taking digoxin: findings from post hoc propensity-matched analysis of the AFFIRM trial. Eur Heart J 34(20):1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht120

Ouyang AJ, Lv YN, Zhong HL, Wen JH, Wei XH, Peng HW, Zhou J, Liu LL (2015) Meta-analysis of digoxin use and risk of mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 115(7):901–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.013

Ziff OJ, Lane DA, Samra M, Griffith M, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Steeds RP, Townend J, Kotecha D (2015) Safety and efficacy of digoxin: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and controlled trial data. Bmj 351:h4451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4451

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj 358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Zhang Y, Akl EA, Schunemann HJ (2018) Using systematic reviews in guideline development: the GRADE approach. Research synthesis methods. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1313

Elayi CS, Shohoudi A, Moodie E, Etaee F, Guglin M, Roy D, Khairy P, Investigators A-C (2020) Digoxin, mortality, and cardiac hospitalizations in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: An AF-CHF analysis. Int J Cardiol 313:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.047

Pastori D, Farcomeni A, Bucci T, Cangemi R, Ciacci P, Vicario T, Violi F, Pignatelli P (2015) Digoxin treatment is associated with increased total and cardiovascular mortality in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 180:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.112

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J (2018) Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health 21(3):95–100. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014

Gheorghiade M, St Clair J, St Clair C, Beller GA (1987) Hemodynamic effects of intravenous digoxin in patients with severe heart failure initially treated with diuretics and vasodilators. J Am Coll Cardiol 9(4):849–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80241-3

Gheorghiade M, Adams KF Jr, Colucci WS (2004) Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation 109(24):2959–2964. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000132482.95686.87

Digitalis Investigation G (1997) The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 336(8):525–533. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199702203360801

Kotecha D, Bunting KV, Gill SK, Mehta S, Stanbury M, Jones JC, Haynes S, Calvert MJ, Deeks JJ, Steeds RP, Strauss VY, Rahimi K, Camm AJ, Griffith M, Lip GYH, Townend JN, Kirchhof P, Control R, therapy evaluation in permanent atrial fibrillation t, (2020) Effect of digoxin vs bisoprolol for heart rate control in atrial fibrillation on patient-reported quality of life: the RATE-AF randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc 324(24):2497–2508. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23138

Pastori D, Carnevale R, Nocella C, Bartimoccia S, Novo M, Cammisotto V, Piconese S, Santulli M, Vasaturo F, Violi F, Pignatelli P, Atherosclerosis in atrial fibrillation Study Group (2018) Digoxin and platelet activation in patients with atrial fibrillation: in vivo and in vitro study. J Am Heart Assoc 7(22):e009509. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.009509

Chirinos JA, Castrellon A, Zambrano JP, Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Horstman LL, Willens HJ, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ, Ahn YS (2005) Digoxin use is associated with increased platelet and endothelial cell activation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm: The Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society 2(5):525–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.016

Bavendiek U, Aguirre Davila L, Koch A, Bauersachs J (2017) Assumption versus evidence: the case of digoxin in atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Eur Heart J 38(27):2095–2099. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw577

Bavishi C, Khan AR, Ather S (2015) Digoxin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 188:99–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.031

Chamaria S, Desai AM, Reddy PC, Olshansky B, Dominic P (2015) Digoxin use to control ventricular rate in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure is not associated with increased mortality. Cardiol Res Pract 2015:314041. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/314041

Wang ZQ, Zhang R, Chen MT, Wang QS, Zhang Y, Huang XH, Wang J, Yan JH, Li YG (2015) Digoxin is associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation regardless of concomitant heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 66(3):270–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000000274

Chen Y, Cai X, Huang W, Wu Y, Huang Y, Hu Y (2015) Increased all-cause mortality associated with digoxin therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine 94(52):e2409. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002409

Qureshi W, O’Neal WT, Soliman EZ, Al-Mallah MH (2016) Systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality and digoxin use in atrial fibrillation. Cardiol J 23(3):333–343. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2016.0016

Zeng WT, Liu ZH, Li ZY, Zhang M, Cheng YJ (2016) Digoxin use and adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Medicine 95(12):e2949. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002949

Sethi NJ, Nielsen EE, Safi S, Feinberg J, Gluud C, Jakobsen JC (2018) Digoxin for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomised clinical trials. PloS One 13(3):e0193924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193924

Vamos M, Erath JW, Benz AP, Lopes RD, Hohnloser SH (2019) Meta-analysis of effects of digoxin on survival in patients with atrial fibrillation or heart failure: an update. Am J Cardiol 123(1):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.09.036

Wang X, Luo Y, Xu D, Zhao K (2021) Effect of digoxin therapy on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 8:731135. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.731135

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, literature search, and data analysis were performed by Gianluca Gazzaniga, Daniele Pastori, Danilo Menichelli, and Alessio Farcomeni. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Daniele Pastori and Gianluca Gazzaniga, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gazzaniga, G., Menichelli, D., Scaglione, F. et al. Effect of digoxin on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation with and without heart failure: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and 12 meta-analyses. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 79, 473–483 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-023-03470-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-023-03470-y