Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore the time-course of hospitalization due to hyponatremia associated with omeprazole and esomeprazole.

Methods

In this register-based case–control study, we compared patients hospitalized with a main diagnosis of hyponatremia (n = 11,213) to matched controls (n = 44,801). We used multiple regression to investigate time-related associations between omeprazole and esomeprazole and hospitalization because of hyponatremia.

Results

The overall adjusted OR (aOR) between proton pump inhibitor (PPI) exposure, regardless of treatment duration and hospitalization with a main diagnosis of hyponatremia, was 1.23 (95% confidence interval CI 1.15–1.32). Exposure to PPIs was associated with a prompt increase in risk of hospitalization for hyponatremia from the first week (aOR 6.87; 95% CI 4.83–9.86). The risk then gradually declined, reaching an aOR of 1.64 (0.96–2.75) the fifth week. The aOR of ongoing PPI treatment was 1.10 (1.03–1.18).

Conclusion

The present study shows a marked association between omeprazole and esomeprazole and hyponatremia related to recently initiated treatment. Consequently, newly initiated PPIs should be considered a potential culprit in any patient suffering from hyponatremia. However, if the patient has had this treatment for a longer time, the PPI should be considered a less likely cause.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hyponatremia is a condition with consequences that range from mild headache and weakness to life-threating brain edema and coma [1]. The prevalence of hyponatremia differs depending on the studied population, but is estimated to be around 30% in hospitalized patients [1]. A wide range of causes can result in hyponatremia including diseases and organ dysfunctions such as pneumonia, liver cirrhosis, and heart failure [2]. However, hyponatremia can also be drug-induced [3]. The list of triggering substances is long and includes several commonly prescribed drugs such as thiazides [4], antiepileptic drugs [5], and antidepressants [6]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have also been associated with hyponatremia [7,8,9,10,11].

PPIs have been used as first-line treatment and prophylaxis of peptic ulcer and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) since the late 1980s [12]. Omeprazole and its S-isomer esomeprazole are the most widely used PPIs today and both compounds are generally well tolerated [13, 14]. Using a population-based approach, we have previously explored the association between hospitalization due to hyponatremia and the use of PPIs, showing that the risk of hospitalization was primarily increased in those that had initiated the treatment within the last 90 days [7, 8]. Detailed knowledge on the time course would be useful to aid clinicians in distinguishing a causal relationship from a spurious association. The aim of this study was to explore the time-course of hospitalization due to hyponatremia associated with omeprazole and esomeprazole.

Methods

This retrospective case–control study investigated the association between omeprazole as well as esomeprazole exposure and hospitalization due to hyponatremia and was based on the entire adult population in Sweden. Omeprazole and esomeprazole are by far the two most commonly prescribed PPIs [12,13,14], collectively referred to as PPIs throughout this article. The index date was defined as the date of admission for each patient. Cases were defined as 18 years old or older persons hospitalized with a first-ever (since 1st of January 1997) main diagnosis of hyponatremia (E87.1) or syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (E22.2) between the 1st of October 2006 and the 31st of December 2014 as identified in ICD-10; the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Data on the ICD-10-encoded diagnoses were retrieved from the National Patient Register (NPR). For each hyponatremic case, four controls without prior diagnosis of hyponatremia were randomly identified in the Total Population Register. Cases and controls were matched for age, gender, and county of residence. The study covered information on diagnoses from the 1st of January 1997 to the 31st of December 2014. Information on drug exposure was retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (SPDR) that includes personal information on all prescription medications sold in Sweden since the 1st of July 2005 [14]. The Swedish longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies register (LISA) was used to collect information about the patients’ socio-economic status. The process has been described in more detail elsewhere [5, 6].

Variables

Omeprazole and esomeprazole were identified by the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) by codes A02BC01, A02BC05, A02BD06, and M01AE52. Exposure to these PPIs was defined as a drug prescription dispensed within 90 days before the index date. New PPI exposure was defined as a prescription of PPIs dispensed within 90 days prior to the index date, without any PPI dispensations during the preceding 12 months. Ongoing use was defined as filled prescriptions of PPI both within the last 90 days prior to the index date and the 12-month period preceding these 90 days. The duration of new PPI usage was further divided into weeks (1–13 weeks) based on date of the first PPI dispensation. Three registers (NPR, SPDR, and LISA) were used to gather data on potential confounders, which encompassed co-morbidities, medications used during the study period, and socioeconomic status. See Table 1 for a summary of all studied variables (both potential confounders and previous exposure).

Statistical analysis

The association between PPI and hospitalization due to hyponatremia was analyzed using logistic regression. Newly initiated (encoded as weeks of exposure as discussed above) and ongoing PPI exposure were included as independent variables, with and without adjustment for potential confounders. Associations were reported as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs), with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For all analyses, R version 3.6.1 was used [15].

Results

Throughout the study period, 11,213 patients with a main diagnosis of hyponatremia (cases) and 44,801 matched controls were identified. The mean age was 76 years and 72% were women (Table 2). Cases suffered from more comorbidities than controls — hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and ischemic heart disease in particular. In addition, cases used more prescribed drugs than controls and more often had a history of hospitalization (Table 2).

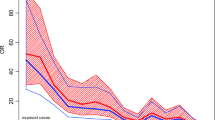

There was a significant association between PPIs exposure regardless of treatment duration and hospitalization with a main diagnosis of hyponatremia, with an adjusted OR (aOR) of 1.23 (95% CI 1.15–1.32). The time-dependent association between the start of PPI-treatment and the date of hospitalization is depicted in Fig. 1. Overall, crude ORs were higher than adjusted ORs. Exposure to PPIs was associated with a prompt increase in risk of hospitalization for hyponatremia from the first week (aOR 6.87; 95% CI 4.83–9.86); the risk then gradually declined reaching an aOR of 1.64 (0.96–2.75) by the fifth week. The aOR of the ongoing PPI treatment was 1.10 (1.03–1.18).

Discussion

Using population-based retrospective data, we explored the time relation between initiation of omeprazole and esomeprazole and hospitalization secondary to hyponatremia in Sweden. The risk was substantially increased from the first week of using PPI and decreased reaching a near normal level by week 5. Ongoing PPI exposure was not associated with the same risk of hyponatremia requiring hospitalization (aOR 1.1).

Previous evidence on the association between PPIs and hyponatremia is scarce and mostly based on small studies [9,10,11]. Buon et al. investigated the prevalence of PPI in elderly individuals with and without hyponatremia (defined as moderate hyponatremia 123–134 mmol/L) [9]. The authors concluded that PPI use was more common among hyponatremic patients. However, due to the limited number of individuals studied (n = 145), the estimate was rather imprecise (OR 4.4 [95% CI (1.8–11]) [9]. Makunts et al. took advantage of post–marketing safety data for PPIs from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System records [10]. The association between omeprazole and esomeprazole and hyponatremia differed substantially (OR 7 vs OR 0.6) which is remarkable considering that omeprazole is a racemic mixture of esomeprazole and the S-isomer of omeprazole. However, with data being based on self-reporting and an analysis that did not control for possible confounders, the results should be interpreted with caution [10]. None of these studies explored the temporal aspects of PPIs and subsequent hyponatremia. The only study exploring the temporal aspects is our previous study, which was based on the same cohort as the present one and found that initiated PPIs (within 90 days) were increased (OR 2.8) while the ongoing use was only slightly increased compared to controls (OR 1.1) [7, 8]. In this study, no large difference was observed in aOR between omeprazole and esomeprazole: 1.67 (95% CI 2.37–3.01) for omeprazole and 2.89 (95% CI 2.21–3.79) for esomeprazole [7, 8]. We did not compare these two PPIs in our study.

Several drug-related side-effects do show a temporal relation with duration of treatment that may represent a vulnerability on behalf of the affected patient. Regarding hyponatremia, such a temporal relationship has been noted for thiazides, antiepileptic drugs, venlafaxine, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tramadol and codeine [4,5,6, 16, 17]. Thus, SSRIs were associated with dramatically elevated risk for hyponatremia from the first week (aOR 29) then gradually declining and normalizing after a few months [16]. Also thiazide-induced hyponatremia has a clear temporal relationship with a risk being substantially elevated immediately after initiation and then declining [4].

The mechanism by which PPI may cause hyponatremia is still unclear but has been attributed to the retention of fluid secondary to an inappropriate ADH secretion (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion SIADH) [1, 2]. Knowledge on the temporal association is interesting as it may help distinguish a spurious relationship from a causal one and potentially guide the clinician when meeting a patient with PPI treatment also suffering from hyponatremia. The present study therefore aimed to investigate the time course of PPI–associated hyponatremia in greater detail. This time, we focused on omeprazole and esomeprazole only, the two most commonly used PPIs, exploring the week-by-week association. The association was immediately substantially elevated reaching an adjusted OR of 7 and then decreased to near normal levels after a month of treatment.

“There were some limitations to our study. Due to the retrospective register-based approach we lacked information on medication adherence. Thus, although we did have information on the time of drugs being dispensed, we could not ascertain if or when they were consumed. Furthermore, apart from being dispensed from pharmacies, omeprazole and esomeprazole are also sold over the counter (OTC). As OTC drugs are not recorded by the registers used, we might have underestimated the proportion of individuals exposed for PPIs among both cases and controls which may have introduced bias. However, in contrast to prescribed drugs, OTC medications are not reimbursed in Sweden, so if more regular use is required it can be assumed to be prescribed. Moreover, we adjusted for the effects of a range of co-morbidities, medications and factors that mirror socioeconomic status, listed in table 1. However, due to the register-based observational approach, we cannot exclude some level of residual confounding. For example, while 15.7% of the cases were associated with previous drug use or diagnosis indicating alcoholism the corresponding proportion among controls was 1.9%. Although the multivariate analysis was adjusted for this imbalance, the ATC-codes and ICD-codes used to define excessive alcohol use might not have mirrored the true proportion which may have introduced bias. The results might therefore be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the database used lacked information on sodium levels. However, a previous validation of the present cohort showed that the mean sodium concentration observed in admitted patients was 121 mmol/L, and that the majority (89%) of patients were judged to be admitted primarily due to low sodium, indicating a high relevance of the outcome used [5].”

The prompt temporal relationship between initiating PPI and hospitalization due to hyponatremia suggests a causal association. However, some of the association may be mediated through the condition for which the initiated PPI was used such as esophagitis or a peptic ulcer, in other words confounding by indication [12,13,14].

The present study has important clinical implications. Newly started PPI treatment should be suspected as the underlying cause in any patient presenting with hyponatremia. The suspicion is strengthened in the absence of concomitant severe disease, such as a bleeding ulcer. However, if a patient has had this treatment for a longer time, other potential causes should be thoroughly investigated before the PPI treatment is abandoned.

In conclusion, the study shows a marked association between omeprazole/esomeprazole and hyponatremia exclusively related to recently initiated treatment. Consequently, newly initiated PPIs should be considered the culprit in any patient suffering from hyponatremia. However, if patients had this treatment a longer time, the PPI should be considered a less likely cause.

Data availability

Data will be made available due to reasonable requests.

References

Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B et al (2014) Hyponatraemia guideline development group. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol 25:170(3):G1–47. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-1020

Adrogue H, Madias N (2000) Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 342(21):1581–1589. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200005253422107

Liamis G, Megapanou E, Elisaf M et al (2019) Hyponatremia-inducing drugs. Front Horm Res 52:167–177. https://doi.org/10.1159/000493246

Mannheimer B, Bergh C, Falhammar H et al (2021) Association between newly initiated thiazide diuretics and hospitalization due to hyponatremia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 77:1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-03086-6

Falhammar H, Lindh J, Calissendorff J et al (2018) Differences in associations of antiepileptic drugs and hospitalization due to hyponatremia: a population-based case-control study. Seizure 59:28–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2018.04.025

Farmand S, Lindh J, Calissendorff J et al (2018) Differences in associations of antidepressants and hospitalization due to hyponatremia. Am J Med 131(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.025

Falhammar H, Lindh J, Calissendorff J et al (2019) Associations of proton pump inhibitors and hospitalization due to hyponatremia: a population-based case-control study. Eur J Intern Med 59:65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.08.012

Falhammar H, Lindh J, Calissendorff J et al (2019) Corrigendum to: associations of proton pump inhibitors and hospitalization due to hyponatremia: a population-based case-control study. Eur J Intern Med 2019 Jan;59:65–69. Eur J Intern Med. 2021 Sep;91:107–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.041. Epub 2021 Jun 24. Erratum for: Eur J Intern Med. 2019 Jan;59:65–69. PMID: 34175185

Buon M, Gaillard C, Martin J et al (2013) Risk of proton pump inhibitor-induced mild hyponatremia in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:2052–2054

Makunts, T, Cohen, I, Awdishu L et al (2019) Analysis of postmarketing safety data for proton-pump inhibitors reveals increased propensity for renal injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and nephrolithiasis. Sci Rep 9:2282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39335-7

Correia L, Ferreira R, Correia I et al (2014) Severe hyponatremia in older patients at admission in an internal medicine department. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Nov-Dec;59(3):642–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.08.002

Ali Khan M, Howden CW (2018) The role of proton pump inhibitors in the management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 14(3):169–175

Bayerdörffer E, Bigard M, Weiss W et al (2016) Randomized, multicenter study: on-demand versus continuous maintenance treatment with esomeprazole in patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol 14(16):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-016-0448-x (PMID: 27080034)

Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored C et al (2007) The new Swedish prescribed drug register–opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(7):726–735. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1294

R.C Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016). https://www.R-project.org/

Mannheimer B, Falhammar H, Calissendorff J et al (2021) Time-dependent association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and hospitalization due to hyponatremia. J Psychopharmacol 35(8):928–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811211001082

Falhammar H, Calissendorff J, Skov J et al (2019) Tramadol- and codeine-induced severe hyponatremia: a Swedish population-based case-control study. Eur J Intern Med 69:20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.08.006

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The cost for retrieval, analysis, and presentation of the data was funded by a clinical trial investigating for the development of diabetic neuropathy (Cebix incorporated, grant number CBX129801-DN-201, Buster Mannheimer) and the Stockholm County Medical Committee (grant number HSTV18048, Jan Calissendorff). Also, the authors received funding from the Magnus Bergvall Foundation (grant number 2021–04226, Henrik Falhammar) and the County Council of Värmland (grant number 930575, Jakob Skov). The funders did not have a role in study design; data collection, analysis, or reporting; or the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jonatan Lindh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Issa Issa, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board (approval number 2015/2270–31/2) in Stockholm, Sweden.

Consent to participate

Due to the retrospective population-based design of this work, that only included de-identified individuals, informed consent to participate was waived.

Consent for publication

Due to the retrospective population-based design of this work, that only included de-identified individuals, informed consent to appear in the subsequent publication was waived.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Issa, I., Skov, J., Falhammar, H. et al. Time-dependent association between omeprazole and esomeprazole and hospitalization due to hyponatremia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 79, 71–77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-022-03423-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-022-03423-x