Abstract

Purpose

Sub-optimal opioid prescribing and use is viewed as a major contributor to the growing opioid crisis. This study aims to systematically review the nature, process and outcomes of interventions to optimize prescribed medicines and reduce their misuse in chronic non-malignant pain (CNMP) with a particular focus on minimizing misuse of opiates.

Methods

A systematic review of literature was undertaken. Search of literature using Medline, EMBASE and CINAHL databases from 2000 onwards was conducted. Screening and selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessments were undertaken by two independent reviewers. Narrative synthesis of the data was conducted.

Results

A total of 21 studies were included in the review, of which three were RCTs. Interventions included clinical (e.g. urine drug testing, opioid treatment contract, pill count), behavioural (e.g. electrical diaries about craving), cognitive behavioural treatment and/or educational interventions for patients and healthcare providers delivered as a single or as a multi-component intervention. Medication optimization outcomes included aspects of misuse, abuse, aberrant drug behaviour, adherence and non-adherence. Although all evaluations showed improvement in medication optimization outcomes, multi-component interventions were more likely to consider and to have shown improvement in clinical outcomes such as pain intensity, quality of life, psychological states and functional improvement compared to single-component interventions.

Conclusions

A well-structured CNMP management programme to promote medicines optimization should include multi-component interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals and target both healthcare professionals and patients. There was heterogeneity in definitions applied and interventions evaluated. There is a need for the development of clear and consistent terminology and measurement criteria to facilitate better comparisons of research evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic non-malignant pain (CNMP) is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as persistent pain regardless of normal tissue healing, for 3 months or more [1]. CNMP is a complex and variable interplay between biological, psychological and social factors. It is categorized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a chronic disease because, it may last a lifetime, can lead to functional impairment, is irreversible and requires patient rehabilitation, frequent medical care and supervision [1]. CNMP prevalence estimates greatly vary, ranging from 8% to 60% in the general population [2, 3]. Adverse clinical, humanistic and economic consequences for patients, families and society have been reported [4].

Medication optimization is defined ‘as a person-centred approach to safe and effective medication usage and to guarantee that patients get the optimal outcomes from their medications’ [5]. Analgesics including opioids are cornerstone in CNMP treatment. Optimizing medicines use in CNMP includes preventing and mitigating ‘problematic behaviour’ in relation to the use of opioids and gabapentinoids in addition to promoting adherence to the prescribed regimen [5]. ‘Problematic behaviour’ is aberrant behaviour suggestive of addiction, misuse or abuse of prescribed opioids for use or administration other than intended by the prescriber and is commonly reported among CNMP patients [6]. A previous literature review demonstrates that up to 50% of CNMP patients are known to demonstrate problematic behaviours [6].

Healthcare professionals face the problem of effectively treating CNMP while preventing inappropriate medications use and as well as promoting appropriate prescribing and de-prescribing. Therefore, clinicians need strategies and assessment tools to help them weigh the risks and benefits of CNMP treatment. Previous systematic reviews have looked at interventions to prevent or reduce opioids misuse [7, 8]. The concept of medicines optimization as a whole has not been investigated. The aim of this study was to systematically review the nature, process and outcomes of interventions used to optimize prescribed medicines use and reduce their misuse in CNMP patients.

Methods

This study was conducted based on the Cochrane Guideline and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (Electronic supplement 1) [4]. Systematic reviews are protocol driven reviews based on priori objectives and plans for literature search, data collection and analyses. Structured approach to identifying, appraising, and synthesizing all relevant studies on a given topic enables researchers to avoid bias in the review process [9]. The protocol was developed as per the PRISMA-P (PRISMA-Protocol) guideline (registered PROSPERO ID = CRD42018111569).

Literature search

Electronic searches were conducted in Medline, EMBASE and CINAHL databases using medical subject headings (MeSH) and free text keyword, including medication adherence, patient compliance, adherent, adherence, non-compliant, noncompliance, non-adherent, non-adherence, chronic pain, chronic non-malignant pain and chronic non-cancer pain. The search was limited to 2000 onwards.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies in the English language using an intervention aimed at optimizing the appropriate usage of prescribed pain medication among adults with CNMP using pain medication for 3 months or more were included. The following concepts were included in medicines optimization: medication adherence, drug misuse, patient compliance to prescribed treatment, including deviation and misuse, adherence/ non-adherence, compliance/non-compliance or safe and effective use of medicines. Studies eligible for inclusion included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized and quasi experimental studies, case-control, cohort and cross-sectional studies published in the English language. Eligible participants were 18+ years with CNMP. Studies involving participants from care homes, residential homes or hospices were excluded as these patients were assumed not to be self-administering their medicines. Both medicines optimization outcomes such as misuse of opioid and clinical outcomes such as pain score, depression and anxiety scale and functional interference were considered.

Screening and selection

Two independent investigators (AA and VP) screened the study abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any conflicts arising regarding the selection were resolved by a third investigator (AY), by discussion or by obtaining the study’s full text.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction form was developed. Data on study characteristics, intervention types and outcome measures were extracted. The two authors independently extracted the data and any disagreement was resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer. For studies utilizing RCT designs, the risk of bias was assessed using the outline criteria of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [9]. The critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) was used for the quality assessment for the rest of the studies.

Two authors (AA and VP) independently performed the assessment, any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third author (AY). Narrative synthesis of the data was conducted because the studies were heterogeneity in definitions, types of interventions, and measurements and reporting methods such as meta-analysis should be conducted when included studies are sufficiently homogeneous in participants involved, interventions, terminology and outcomes to provide a precise summary [10].

Results

From 952 records initially identified, 21 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The reasons for study exclusion are detailed in the Supplementary Material. Of the 21 included studies, three were RCTs and 18 were observational designs.

Methodological quality

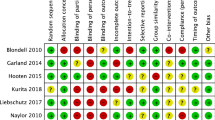

RCTs

The three RCTs were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane tool [9]. All three studies [11,12,13] were judged to be at high risk of selection bias, due to the lack of clarity provided regarding the sequence generation process and allocation concealment of participants (Table 1).

Other study designs

The quality of the quasi-experimental (n = 18) was measured using the CASP quality assessment tool (Table 2). All 18 studies addressed a clear study aim. The majority (n = 14) did not provide adequate information on the recruitment procedure (n = 14). Five studies mentioned how the outcomes were measured, four studies did not and the others (n = 9) were unclear (Table 2).

Characteristics of included studies

The studies were published between 2003 and 2018. Eighteen were conducted in the United States [11, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], and the remainder in Denmark [30], Germany [31] and the Netherlands [12]. Three studies were RCT (Table 3) [11,12,13]. Nine studies used prospective cohort design [15, 17, 20, 23, 24, 28, 30]. Seven were retrospective cohort studies [18, 19, 21, 22, 25,26,27] one was a cross-sectional design [31] and one was pre-post interventional design without a control arm [16]. Six studies were conducted in primary care settings [17,18,19, 25, 27, 29], four in pain centres [23, 24, 28, 31], seven in outpatient’s pain clinics [14, 15, 22, 26, 29, 31], two recruited patients from primary care and pain clinics [16, 20] and one recruited patient from primary care and an internet site (Table 3) [13].

Medicines optimization goals

Most of the included studies aimed to reduce the use or misuse/abuse of drugs or aberrant drug behaviour or to enhance appropriate use of prescribed opioids in CNMP patients. Four of the included studies aimed to reduce the use or reliance on opioids [13, 19, 25, 30], nine aimed to identify and reduce misuse, abuse of drugs or aberrant drug behaviour [11, 14, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 28, 29]. Two studies aimed to improve adherence (n = 2) [12, 16] and four focused on patients’ compliance with prescribed opioids [11,18, 22, 31]. Considering pain type and locations, eight studies included both nociceptive and neuropathic pain patients [12, 13, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 31]. Eight studies focused on populations suffering from nociceptive pain, including low back pain, arthritis and other musculoskeletal disorders [11, 15, 20, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30]. Five studies did not specify the type of pain or provided insufficient patients’ information [14, 16, 19, 26, 29]. None of the studies focused on other types of analgesics, especially co-analgesic medication (such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants) (Table 3).

Medication taking behaviour

The scope of medication taking behaviour was defined differently among the included studies. These included misuse [11, 17, 28], abuse [23], aberrant drug-taking behaviour [14, 19, 21], non-adherence(n = 3) [12, 15, 16], compliance (n = 3) [18, 22, 31] and illicit drug use (n = 1) [24]. Seven studies did not define any medication taking behaviour [13, 20, 25,26,27, 29, 30].

Tables 3 and 4 to be included here.

Type of interventions

Single component interventions

Opioid treatment contract (OTC) with or without urine drug screening (UDS)

A total of 11 studies used single component interventions (Table 4). An OTC is a bilateral contract between the patient and physician that defines each party’s responsibilities. These included OTC alone or combined with urine drug screening to measure patients’ adherence to the contract terms (Table 4). Only three studies published a copy or details of the OTC [15, 17, 18].

Behavioural interventions

Five studies used different behavioural approaches alone either to reduce misuse, abuse or to reduce patient reliance on opioids, while one aimed to improve patient opioid adherence (Table 4). These include working alliance, which refers to the mutual relationship that grows between the therapist and patient during the treatment period [14], cognitive and behavioural treatments based on attachment orientations, which are defined as moderately stable schemas that regulate emotions and our responses to health behaviour and stressors [30]; in-clinic electronic diaries to answer 25 questions to monitor patients’ craving progress [28]; brief office-based introductory motivational interviews on the adherence to opioid medication [16]; and internet-based pain management programme for targeting behavioural, cognitive, emotional and social factors [13].

Educational interventions

Only one study evaluated the effect of specific medication education on patients’ adherence to their medication using a brief video and written instruction about the medication name, dosage, and frequency [12].

Multi-component interventions

Multi-component interventions were used by ten studies (Table 4). Each intervention included at least three components along with UDS and OTC. Most of these programmes followed the relevant local or national clinical practice guidelines for managing opioid therapy for chronic pain. The components of complex interventions included the following:

-

1.

Urine drug screening and opioid treatment contract within multi-component intervention

All the included studies categorized as multi-component interventions incorporated OTC. The studies generally included UDS alongside OTC (Table 4).

-

2.

Monthly clinical/pain assessment

Seven studies of complex intervention studies involved a monthly physical or pain assessment (Table 4).

-

3.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment was used to help determine risk potential for ‘Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviour’ (ADRB) (Table 3). Three studies used the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Pain Patients-Revised (SOAPP-R) questionnaire, a standardized score tool that can be answered by patients or their providers [19, 26, 27] (Table 4). One study used the opioids/benzodiazepines combination risk assessment tool created by the study team as YES/NO questions [26]. Other studies stated that ADRB was identified by self-reporting or evaluated by the healthcare providers using other tools but did not mention using a standardized questionnaire [19].

-

4.

Prescription monitoring programme (PMP)

PMP are state-based electronic databases that are used to track prescriptions, mainly for controlled substances, including benzodiazepines, opioids and amphetamines. Five studies used PMP to optimize pain medication use and reduce inappropriate use (Table 4).

-

5.

Opioid dose adjustments

Six studies used average daily Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) adjustment as an intervention to optimize medication use (Table 4).

-

6.

Prescribing/dispensing small quantities/pill count

Three studies included pill counts or small quantities of opioids [15, 23, 29]. Pill count was described as done in a random selection method; however, it was not clear who performed the count [23] (Table 4).

-

7.

Team-based approach

Six studies used a team-based approach led by one or multiple providers [17, 19, 25,26,27, 29]. These included the combined skills of clinical pharmacist, internist and psychiatric [17], use of a structured package containing documents to be filled by patients regarding pain history medication use, psychiatric evaluation and educational information [25], a primary care provider run outpatient clinic and aided by dedicated nursing, pharmacy and mental health care providers [26], pharmacists run opioid use clinic and informal consultative services in primary care including the use of telephone [19], multidisciplinary pain management team who met bi-weekly to review cases and recommend treatment plans [29].

-

8.

Patient education within a multi-component intervention

Only two studies involved patient education as a component of their interventions [11, 26]. These included printed educational material [26] and group sessions [11].

-

9.

Provider education within a multi-component intervention

Three studies educated or trained providers before participating in the studies [15, 20, 26]. These included pain management education and monitoring techniques.

-

10.

Behavioural interventions within a multi-component intervention

Only one study offered behavioural intervention as a part of a complex intervention where patients participated in a structured motivational and cognitive behavioural training programme to prevent substance misuse [11].

-

11.

Psychiatric consultation

Four studies included a psychiatric consultation plan or a psychiatrist as part of the treatment programme [11, 17, 26, 29]. The studies differed in role and goal of including this component which included psychiatric consultation as support for patients at high risk of misuse, abuse and addiction [11, 17, 29] assessment of patient risk, stability and the presence of contraindications of using an opioid/BZD combination to treat CNMP [26].

-

12.

Electronic diaries

Only one study used electronic diaries to monitor cravings among patients and the effect is reported briefly in the study [11].

Study outcomes

There was substantial heterogeneity on the nature of the outcomes (Table 5). These were systematically categorized as follows:

Medicine optimization

-

(a)

Appropriate use of pain medication: Twelve studies aimed to enhance appropriate use, three measured patients’ adherence [12, 14, 16], seven studies measured the reduction of patient’s opioids dose or reliance on opioids [13, 19, 25,26,27, 29, 30], four measured patients’ compliance [20, 22, 28, 31].

-

(b)

Inappropriate use of pain medication: Twenty studies aimed to reduce the problematic medication-taking behaviour including misuse, abuse, illicit drug use, seven of these measured aberrant drug behaviours [11, 15, 18, 19, 21, 24, 29], seven measured abuse [11, 14, 16, 18, 23, 27, 29] and six measured misuse [11, 13, 16, 17, 20, 27].

-

(c)

Self-discharge from chronic opioid treatment

Some patients voluntarily discontinued chronic opioid therapy after implementing a structured opioid programme observed in three studies [18, 25, 27].

Clinical outcomes

Only nine studies assessed clinical outcomes such as pain intensity or functional improvement, depression and anxiety [11,12,13,14, 16, 17, 20, 25, 30]. One study measured patients’ quality of life using the quality of life scale [25] (Table 5).

Other outcomes utilized

These included patient satisfactions [11, 12, 16, 20], reduction in utilization of health care services [13, 29], healthcare costs [27, 29], provider confidence in managing CNMP patients, compliance with universal precautions [20], adherence to clinical guidelines [15, 19, 20, 26, 27, 29, 30] and provider satisfaction [27, 29].

Impact of the interventions

UDS was used in simple intervention and complex interventions as the only objective tool to detect inappropriate drug-taking behaviours. The use of UDS was associated with significant reduction in inappropriate medication use [11, 17, 22, 24, 31] (Table 5). For example, in a study which aimed to identify controlled substance abuse in patients receiving prescription opioids showed a statistically significant decreases in obtaining opioids from multiple providers or sources from 17.8% to 9.2% (ARR, 8.6% [CI, 4.4% to 12.8%]) [23]. One study concluded that UDS should not be used alone and should be used with a comprehensive monitoring system [21].

Three studies that were conducted in a pain speciality setting and used UDS and OTC found these were associated with improvements in detecting inappropriate drug-taking behaviours but did not measure clinical outcomes such as pain intensity and depression score [21, 23, 24]. Two studies that used the same sample of patients and used historical control participants concluded that UDT and OTC significantly reduced the problematic behaviour by detecting patients who were obtaining opioids from multiple providers [23, 24]. Behavioural interventions showed that these interventions are beneficial in reducing the inappropriate use of medication, pain intensity and depression score and in improving patient compliance [14, 16, 30]. Another study suggested that careful monitoring of patients’ medication cravings can reduce the inappropriate use of medication and the level of pain experienced is weakly associated with craving opioids [28]. Only one study used special medication educational intervention alone and found a non-significant effect on medication optimization and no significant effect on pain intensity, depression and functionality interference [12].

Overall, treatment programmes incorporating multidisciplinary teams were associated with decreased risk of opioid misuse and improved functioning and pain condition [11, 14, 17, 25, 28]. One study that used a pharmacist and nurse-led interdisciplinary approach in advising primary healthcare providers, prescription management and patient monitoring using UDS in the opioid renewal clinic showed that approximately half who were referred for complexity, including history of substance abuse or need for opioid rotation or titration, continued to adhere to the opioid treatment plan [29]. While in another study that aimed to support providers and change prescribing behaviours and improve their adherence to clinical guidelines, reported that opiate use was successfully discontinued in nearly one in ten patients [19]. Generally the structured programme were associated with a reduction in the inappropriate use of medication but clinical outcomes such as depression, pain, and quality-of-life scores were stable during study time were rarely reported [25] (Table 5). A study which included daily patient visits to a primary care physician clinic and involved verification of the controlled substance contract, UDS, board of pharmacy monitoring, pain-targeted history and physical, calculation of the average morphine equivalents used showed that 8% elected to wean opioids, 53% continued opioid medication and 9% transferred care. Mean morphine equivalent mg/day was the prime determinant for ability to wean (17.01 mg/day) compared with maintaining (30.61 mg/day) (p = .0397; CI, 0.68 to 26.51) [25]. Patients maintaining opioid treatment showed no statistically significant change in clinical outcomes such as quality of life and depression scale point compared with the baseline [25]. Another study conducted in a multidisciplinary primary care programme monitored patients with psychiatric comorbidity showed an improvement in patients’ mood and pain scores but, a high dropout rate reported among patients with misuse behaviour was observed [17]. An RCT consisting of monthly electronic diaries, urine toxicology screens and medication adherence counselling for six months reported an improvement to prescribed regimen among high risk patients adherence and patients satisfaction (Table 5) [11].

Discussion

This study aimed to systematically review the nature and outcomes of interventions to optimize the use of prescribed medication among CNMP patients. An array of different types of single component and multi-component complex interventions were being evaluated to optimize medication use. A variety of definitions were used for medication optimization with a range of other outcomes evaluated which included clinical outcomes, costs, patients and healthcare satisfaction and quality of life.

The results demonstrate an inadequate number of high-quality studies focusing on medication optimization among these patients. The majority of studies (n = 10) had a limited sample size and were often conducted in a single setting. Studies differed in recruitment methods and participant inclusion criteria. In addition, there was substantial heterogeneity in the types of populations being studied, their co-morbidities and medications. Studies were of low to moderate quality. It was often unclear which component targets which behavioural issue. A lack of consistency in defining the appropriate use of pain medication was identified.

Most of the studies categorized as simple interventions aimed either to detect or reduce the problematic taking behaviours without taking into consideration their effects on patients’ clinical outcomes such as pain intensity, depression, anxiety and relapse after stopping their medication [18, 21,22,23, 31]. A previous qualitative study suggested that healthcare providers commonly believed that OTAs were useful for provider self-protection, but they do not prevent opioid misuse [32].

The multi-component interventions included in this review were often based on the United States’ own chronic pain management guidelines such as Department of Defence Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain [26, 27]. Such multi-component interventions were shown to be more comprehensive and targeted detection and reduction of problematic medication-taking behaviour, taking into consideration patients’ physical and psychological states, as well as their satisfaction [26, 27]. However, the complexity of these interventions makes it unclear to conclude which components targeted which behaviour. Such understanding is needed in order to personalize the interventions for the CNMP population which may differ in various way and from one demographic region to another. For example, patients with a history of addictions and other substance use disorder may need different monitoring than those without such issues [11, 15, 17]. Safe and effective pain management requires knowledge of the principles of chronic opioid therapy as well as effective assessment of risks associated with opioid abuse, addiction and diversion using multi-component interventions. An earlier systematic review specifically focused on opioid misuse also addressed that multi-component interventions that targeted both patients and healthcare professionals are essential to minimize their misuse for CNMP patients [33].

The lack of literature regarding interventions for non-opioid medication and the heterogeneity of studies are major limitations of the published literature.

Implications for practice

The review suggests that the most promising approach to increase the appropriate use of prescribed pain medication among CNMP patients is a structured opioid clinic with multidisciplinary approach. Clinician ability to appropriately prescribe opioids to CNMP patients with or without problematic medication taking behaviour can be achieved with an appropriate level of understanding and using the components of the complex interventions including UDS and OTC and personalizing pain management according to patient need. Random drug testing might be more suitable to detect misuse and abuse than regular testing and save more money. Well-structured chronic pain program/structured opioid clinic designed to support and improve healthcare providers, communication skills and knowledge for all healthcare providers should be implemented. More attention should be paid to the costs and benefits and of interventions and the impact on clinical staff on the burden as this is potentially important to inform policy and practice decisions [27].

Collaborative relationships and communication between different healthcare settings are important to facilitate medication optimization. Providing high quality, patient-centred care and ensuring patient safety for CNMP patients who are on chronic opioid therapy requires collaboration among healthcare providers [34]. Clinicians need to attend more to the negative impact of psychiatric and behavioural issues on the use of opioids. Additionally, they should initiate discussions with patients who are being prescribed opioids in order to evaluate their medication-taking behaviours and treatment effectiveness, as well as to screen for their risk of prescription opioid misuse and provide intervention as needed. Clinicians must be aware CNMP patients face multiple physical, psychological and social challenges that may impede them from taking their medications as prescribed [35,36,37].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review to include a wide variety of studies on the nature and outcomes of interventions used to optimize medicines use in CNMP patients. The search was limited to three databases and the English language. The search criteria did not include specific chronic pain type or diagnoses, which might have led to the omission of studies.

Implications for research

There is a need for further studies on interventions to optimize the use of prescribed pain medication, applying high methodological standards and including randomized controlled designs. There is also a need for future studies to better define misuse and other problematic medication-taking behaviour and related complications of opioid therapy, to develop diagnostic procedures for these disorders. Moreover, behavioural issues should be categorized according to their seriousness and their effect on the patient’s quality of life. The studies should also report changes in outcome measurements such as pain levels and psychosocial, physical and occupational functioning and patient’s satisfaction at different time points, rather that only before and after the intervention implementation. The validity and reliability of measurement tools should be carefully tested and explicitly reported. Both interventions and tests should be tailored to specific CNMP populations such as patients with different types of pain, comorbid psychiatric conditions and different behavioural issue. Future efforts should be directed at RCT to examine structured pain management programs that would determine whether reported effects are real examined durability and promote their sustainability. There is also a need for the development of clear and consistent terminology and measurement criteria to facilitate comparisons of research evidence. Research should assess the drawbacks of applying these interventions. Future interventions should include collaborative and structured opioid clinic approaches using nurse, pharmacist or a primary care physician who must be trained in delivering a motivational interview or educational interventions.

Conclusion

A well-structured CNMP management programme to promote medicines optimization should include multi-component interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals and target both healthcare professionals and patients. There was heterogeneity in definitions applied and interventions evaluated. There is a need for the development of clear and consistent terminology and measurement criteria to facilitate better comparisons of research evidence.

References

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB (2015) First MB, Giamberardino MA. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 156(6):1003

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D (2006) Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 10(4):287

Verhaak PFM, Kerssens JJ, Dekker J, Sorbi MJ, Bensing JM (1998) Prevalence of chronic benign pain disorder among adults: a review of the literature. Pain 77:231–239

Phillips CJ (2009) The cost and burden of chronic pain. Rev Pain 3:2–5

NICE (2015) Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE Guideline. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/resources/medicines-optimisation-the-safe-and-effective-use-of-medicines-to-enable-the-best-possible-outcomes-51041805253. Accessed 24 Sept 2020

Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN (2015) Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 156:569–576

Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, Kapoor A, Williams AR, Turner BJ (2010) Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 152:712–720

McCarberg BH (2011) Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad Med 123:119–130

Higgins JPT, Green S ( ed) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009] The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.Accessed 25/09/2020

Stewart LA, Clarke MJ (1995) Practical methodology of meta-analyses (overviews) using updated individual patient data. Cochrane working group Stat Med 14:2057–2079

Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, Chen LQ, Holcomb C, Wasan AD (2010) Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: a randomized trial. Pain 150:390–400

Timmerman L, Stronks DL, Groeneweg G, Frank JPMH (2016) The value of medication-specific education on medication adherence and treatment outcome in patients with chronic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Pain Med 17:1829–1837

Wilson M, Roll JM, Corbett C, Barbosa-Leiker C (2015) Empowering patients with persistent pain using an internet based self-management program. Pain Manag Nurs 16(4):503–514

Bethea AR, Acosta MC, Haller DL (2008) Patient versus therapist alliance: whose perception matters? J Subst Abus Treat 35(2):174–183

Brown J, Setnik B, Lee K, Wase L, Roland C, Cleveland J, Siegel S, Katz N (2010) Assessment, stratification, and monitoring of the risk for prescription opioid misuse and abuse in the primary care setting. J Opioid Manag 7:467–483

Chang Y-P, Compton P, Almeter P, Fox CH (2015) The effect of motivational interviewing on prescription opioid adherence among older adults with chronic pain. Perspect Psychiatr Care 51(3):211–219

Chelminski PR, Ives TJ, Felix KM et al (2005) A primary care, multi-disciplinary disease management program for opioid-treated patients with chronic non-cancer pain and a high burden of psychiatric comorbidity. BMC Health Serv Res 5:3–10

Hariharan J, Lamb GC, Neuner JM (2007) Long-term opioid contract use for chronic pain management in primary care practice. A five year experience. J Gen Intern Med 22:485–490

Jacobs SC, San EK, Tat C, Chiao P, Dulay M, Ludwig A (2016) Implementing an opioid risk assessment telephone clinic: outcomes from a pharmacist-led initiative in a large veterans health administration primary care clinic, December 15, 2014-march 31, 2015. Subst Abus 37(1):15–19

Jamison RN, Scanlan E, Matthews ML, Jurcik DC, Ross EL (2016) Attitudes of primary care practitioners in managing chronic pain patients prescribed opioids for pain: a prospective longitudinal controlled trial. Pain Med 17:99–113

Katz NP, Sherburne S, Beach M, Rose RJ, Vielguth J, Bradley J, Fanciullo GJ (2003) Behavioral monitoring and urine toxicology testing in patients receiving longterm opioid therapy. Anesth Analg 97:1097–1102

Knezevic NN, Khan OM, Beiranvand A, Candido KD (2017) Repeated quantitative urine toxicology analysis may improve chronic pain patient compliance with opioid therapy. Pain Physician. 20(2S):S135–S145

Manchikanti L, Manchukonda R, Damron K, Brandon D, McManus C, Cash K (2006) Does adherence monitoring reduce controlled substance abuse in chronic pain patients? Pain Physician 9:57–60

Manchikanti L, Manchukonda R, Pampati V, Damron KS, Brandon D, Cash K, McManus C (2006) Does random urine drug testing reduce illicit drug use in chronic pain patients receiving opioids? Pain Physician 9:123–129

McCann KS, Barker S, Cousins R et al (2018) Structured management of chronic nonmalignant pain with opioids in a rural primary care office. J Am Board Fam Med 31:57–63

Schell RF, Abramczyk AM, Fominaya CE et al (2017) Outcomes associated with a multidisciplinary pain oversight committee to facilitate appropriate management of chronic opioid therapy among veterans. Fed Pract 34(6):18–26

Talusan R, Kawi J, Candela L, Implementation FJ (2016) Evaluation of an APRN-led opioid monitoring clinic. Fed Pract 33(11):22–27

Wasan AD, Ross EL, Michna E, Chibnik L, Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Jamison RN (2012) Craving of prescription opioids in patients with chronic pain: a longitudinal outcomes trial. J Pain 13:146–154

Wiedemer NL, Harden PS, Arndt IO, Gallagher RM (2007) The opioid renewal clinic: a primary care, managed approach to opioid therapy in chronic pain patients at risk for substance abuse. Pain Med 8:573–584

Andersen TE (2012) Does attachment insecurity affect the outcomes of a multidisciplinary pain management program? The association between attachment insecurity, pain, disability, distress, and the use of opioids. Soc Sci Med 74:1461–1468

Kipping K, Maier C, Bussemas H, Schwartzer A (2014) Medication compliance in chronic pain. Pain Physician 17(1):81–94

Starrels JL, Wu B, Peyser D et al (2014) It made my life a little easier: primary care providers’ beliefs and attitudes about using opioid treatment agreements. J Opioid Manag 10:95–102

Kaye AD, Jones MR, Kaye AM et al (2017) Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: an updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse: part 2. Pain Physician 20(2S):S111–S133

Kashiri PL, Krist AH (2019) Chronic opioid prescribing in primary care: factors and perspectives. Ann Fam Med 17(3):200–206

Paudyal V, MacLure K, Buchanan C, Wilson L, McLeod J, Stewart D (2017) When you are homeless, you are not thinking about your medication, but your food, shelter or heat for the night': behavioural determinants of the homeless population adherence to prescribed medicines. Public Health 148:1–8

Gunner E, Chandan SK, Marwick S, Saunders K, Burwood S, Yahyouche A, Paudyal V (2019) Provision and accessibility of primary healthcare services for people who are homeless: a qualitative study of patient perspectives in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 69(685):e526–36

Bowen M, Marwick S, Marshall T, Saunders K, Burwood S, Yahyouche A, Stewart D, Paudyal V (2019) Multi-morbidity and emergency department visits by a homeless population: a database study in specialist general practice. Br J Gen Pract 69(685):e515–25

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Birmingham Library services for their support in the search process.

Funding

This work funded by the University of Birmingham. AA was sponsored for her PhD by the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Cultural Bureau in London for her PhD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study relates to AA’s PhD study. VP and AY supervised AA for her PhD. All authors co-designed the study. AA led the write up to which all authors contributed through editing before final submission. AA led the searching, screening and data extraction to which the other authors contributed as independent reviewers. All authors had access to the datasets and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Data statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A protocol developed as per the PRISMA-P guideline is registered under PROSPERO ID=CRD42018111569.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alenezi, A., Yahyouche, A. & Paudyal, V. Interventions to optimize prescribed medicines and reduce their misuse in chronic non-malignant pain: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 77, 467–490 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-03026-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-03026-4