Abstract

Purpose

Older people with dementia are at risk of adverse events associated with potentially inappropriate prescribing. Aim: to describe (1) how international tools designed to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing have been used in studies of older people with dementia, (2) the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in this cohort and (3) advantages/disadvantages of tools

Methods

Systematic literature review, designed and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P). MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, the Social Science Citation Index, OpenGrey, Base, GreyLit, Mednar and the National Database of Ageing Research were searched in April 2016 for studies describing the use of a tool or criteria to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people with dementia.

Results

Three thousand three hundred twenty-six unique papers were identified; 26 were included in the review. Eight studies used more than one tool to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing. There were variations in how the tools were applied. The Beers criteria were the most commonly used tool. Thirteen of the 15 studies using the Beers criteria did not use the full tool. The prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing ranged from 14 to 74% in older people with dementia. Benzodiazepines, hypnotics and anticholinergics were the most common potentially inappropriately prescribed medications.

Conclusions

Variations in tool application may at least in part explain variations in potentially inappropriate prescribing across studies. Recommendations include a more standardised tool usage and ensuring the tools are comprehensive enough to identify all potentially inappropriate medications and are kept up to date.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is estimated that 47 million people worldwide are living with dementia, and this is set to increase to more than 131 million by 2050 [1]. People with dementia experience higher levels of co-morbidities and may receive on average more medications than their cognitively intact counterparts [2]. They may also receive suboptimal care that includes poor pain control [3, 4] and prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) [5].

Prescribing is potentially inappropriate where there are drug–disease or drug–drug interactions, where the risks of a medication outweigh the benefits, where there is a lack of evidence for a medication or where time to benefit of treatment exceeds an individual’s life expectancy [6]. Potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) has been associated with an increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs), hospitalisation, mortality and lower quality of life in older people with and without dementia [7, 8].

Many tools have been developed to identify PIP in older people for use in research and in clinical settings. An overview of published tools identified 46 different tools for identifying PIP, of which 36 were developed for use with older people and 6 for use in long-term care settings [9]. The most commonly used tool is the Beers criteria which were first published in 1991 and have been regularly updated since [10,11,12,13,14]. They include lists of medications considered inappropriate for older people in general and also provide a list of PIMs for specific conditions such as dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Another commonly used tool is the STOPP START criteria which in addition to identifying medications that may need to be stopped also identify where there may be a potential under-use of medications [15, 16]. The content of the different tools varies, and there is a lack of consensus about what medications are inappropriate and under what circumstances [17, 18].

Several studies have been published that describe and compare tools to identify PIP; however, they have focused on identifying PIP in older people in general. [9, 18, 19]. To date, there has not been a systematic review that has assessed how the tools are being utilised in studies of PIP in older people with dementia. Given the higher number of co-morbidities and the increased drug burden experienced by this group compared with their non-cognitively impaired counterparts [2, 20], a systematic review of studies utilising tools to identify PIP in this cohort is an essential addition to the literature.

The aims of the review were:

-

1.

To describe and summarise studies that have used a published tool to identify PIP in people with dementia.

-

2.

To report the prevalence of PIP and the medications identified as inappropriate in the included studies.

-

3.

To describe the potential advantages, disadvantages or complications of using the tools as identified by the authors of the included studies.

Methods

The review was conducted according to the recommendations set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [21].

Search strategy

A systematic search of the published peer-reviewed literature and grey literature was conducted in April 2016. Literature search strategies were developed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and text words around the topic of dementia and inappropriate prescribing (The Appendix Table 3 documents the full search strategy for Medline, which was then adapted as appropriate for the other databases). The following databases were searched: Medline (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO Host), Embase (Ovid), PsycInfo (Ovid), Social Science Citation Index (Web of Science) and the Cochrane Library (Wiley). There was no restriction by year of publication. Searches were also conducted for grey literature using the following online databases: OpenGrey, Grey Literature Report, Mednar, BASE and the National Database for Ageing Research. A search of the reference lists of retrieved papers was also conducted. Table 1 lists the criteria for including studies in the systematic review.

Data extraction, assessment and analysis

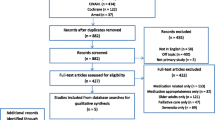

Two authors (DH and JB) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. The full papers for references that appeared to meet the criteria, or those for which there was uncertainty, were retrieved for independent review by both authors (DH and JB). Where there was disagreement about which papers should be included, these were resolved by discussion. The third author (UM) was available to resolve any ongoing disagreements about inclusion. Where there were any exclusions of full-text articles, the reason for exclusion was recorded (Fig. 1).

A standardised list of data to be extracted was created, based on the aims and objectives of the review. The data extracted were authors and year of publication, study aims and objectives, study design, tools used, study setting, sample size, demographic data, prevalence of polypharmacy, prevalence of PIP, most commonly prescribed PIP medications, summary of main findings, strengths and limitations of the tools and author’s conclusions. The data were extracted independently by two of the authors (DH and JB) and any disagreements resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

Critical appraisal of the included papers was conducted using the Hawker Tool [22]. The papers were independently assessed by two of the authors (DH and JB) for methodological quality and risk of bias. Studies were weighted but were not to be excluded from the review on the basis of quality. This tool was chosen because it has been designed to be used to assess study quality for multiple study designs and has been used for this purpose in previous systematic reviews [23,24,25,26,27,28]. The Hawker Tool assesses the reporting of a study in the following areas: abstract and title, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, findings and results, transferability and reliability, and implications and usefulness. Each of the nine areas is given a score of either 1 (very poor), 2 (poor), 3 (fair) or 4 (good) which gives a total overall score out of 36 for each paper [22].

Results

Search results

The search of biomedical databases identified 4597 papers, and a further 712 were identified through the grey literature search and hand searching of reference lists. After removal of duplicates, there were 3626 unique studies. After eligibility screening, 47 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion, of which 26 papers were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

The Hawker score for the included studies ranged from 22/36 [29, 30] to 36/36 [31, 32]. The median total score was 29/36. Previous reviews using the Hawker Tool [22] have set a cut-off of 20/36 or above to indicate a study that is of a fair to good quality [25, 27]. On this basis, all 26 studies would be classed as at least fair quality. Overall, the studies scored lowest for reporting on Ethics and Bias and also Transferability and Reliability (Appendix Table 4).

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 2 outlines the characteristics of the 26 included studies including study design, tools used to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing, country, setting, participants and summary of results. Twenty-five studies were observational that used at least one tool to measure the prevalence of PIP [2, 5, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. One study was a non-randomised evaluation of an intervention to improve medication management [30].

Across all 26 studies, 26,534 participants were recruited, of which 21,285 (80%) had dementia or cognitive impairment, 968 (4%) had mild cognitive impairment and 4281 (16%) were non-cognitively impaired controls. A total of 17,928 of the participants were female (68%). Mean age ranged from 72.5 [2] to 86.8 [5].

Number of medications and the prevalence of polypharmacy

Ten studies reported a range for number of medications prescribed; this was from 0 to 22 [5, 32, 33, 35, 37, 46,47,48, 50, 51]. Mean number of medications was reported in 19 studies [2, 5, 29,30,31,32, 34, 36, 37, 40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48, 50, 51] and ranged from 4 [50] to 14 [31]. When comparing the mean number of medications between those with and without dementia, results were mixed, with two studies reporting a significantly lower mean number of medications in those with cognitive impairment [43, 45] and, by contrast, two studies reporting a significantly higher number in those with cognitive impairment [2, 41].

Eleven studies reported the prevalence of polypharmacy as the percentage of participants taking ≥ 5 medications [2, 30,31,32, 35, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 51]. The prevalence of polypharmacy ranged from 25% [38] to 98% [51] for people with dementia or cognitive impairment (see Table 2).

Prevalence of PIP

The prevalence of PIP was reported as the percentage of the cohort taking at least one potentially inappropriate medication. For people with dementia, this ranged from 14% [44] to 74% [31]. For non-cognitively impaired controls, the prevalence ranged from 11% [2] to 44% [43] (see Table 2).

In studies comparing the prevalence of PIP between those with and without cognitive impairment or dementia, two studies found a significantly higher prevalence in those with dementia [2, 39], three found a significantly lower prevalence in those with dementia [41, 43, 47], and two found no significant difference between the groups [31, 37].

The most commonly prescribed potentially inappropriate medications were anxiolytic–hypnotics and anticholinergic medications [2, 29, 31,32,33, 35, 37,38,39, 43,44,45,46,47, 50, 51]. Rates of anticholinergic prescription ranged from 6% [45] to 46% [32]. Rates of anxiolytic–hypnotic (including benzodiazepines) use ranged from 5% [43] to 38% [51]. Other commonly prescribed potentially inappropriate medications included lipid-lowering medications [34, 48, 49] and antiplatelets [34], oestrogens [36, 40, 41, 47], non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [5, 36, 47], antipsychotics [5] and proton pump inhibitors [5].

The use of a tool to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing

The Beers criteria [11,12,13] were the most commonly used of the tools (Table 2). Thirteen out of the 16 studies that used the Beers criteria did not apply the full tool. Of these, seven studies only used the list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people in general [29, 40,41,42, 45, 47, 52] and four applied only the disease-specific part of the tool [33, 35, 38, 39]. Two studies were unable to apply the full criteria as some medications were unavailable in the countries that the studies were located [43, 46].

Three of the five studies using the Holmes criteria [57] defined potentially inappropriate medications as only those drugs on the ‘Never Appropriate’ list [38, 48, 49], one defined potentially inappropriate medications as those on the ‘Never Appropriate’ and ‘Rarely Appropriate’ lists [34] and one applied the whole criteria to their dataset [50]. Three of the studies using the STOPP START [15] applied only the STOPP criteria to their data [2, 5, 35].

Eight studies utilised at least one additional tool to identify potentially inappropriate medications, five of which used a published tool to identify anticholinergic medications [2, 32, 35, 39, 46]. Four studies used an additional list of potentially inappropriate medications devised by the authors [39, 42, 43, 46].

Problems using the tools

Seventeen studies identified potential issues associated with using the tools [5, 30, 31, 33, 35, 38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. One problem identified was the consensus methods used to develop the tools meant the risk benefit profile was subjective [33, 38]. In addition, the NORGEP criteria did not include drugs that may be inappropriate for specific co-morbidities and as such may have resulted in an underestimation of the prevalence of PIP [44].

Also, the type of data collected would determine the extent to which the criteria could be applied. For example, one study could only apply 31 out of the 65 STOPP criteria [15] because of a lack of diagnostic information available in the notes [5]. The authors note that this lack of information could in itself contribute to inappropriate prescribing [5].

Two versions of the Beers criteria [11, 12] were not easily applied in countries outside of the USA because some medications listed were not available in other countries [42, 43, 45, 46]. One study compared the Beers criteria [12] and the Laroche List [59] and found a higher prevalence of PIP using the latter [42]. The authors argue this demonstrates the Laroche List [59] is better suited to a European population. In addition, another study identified that the Beers criteria [12] needed to be updated to include more sedative and anticholinergic medications [40].

The Holmes criteria [57] may need more validating and updating. The authors of the studies using this tool highlighted that some medications may have been placed in the wrong category given more recent evidence for their use in older adults with advanced dementia [38, 48,49,50].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to describe how tools designed to identify PIP were being used in studies of older people with dementia. In this review, the majority of included studies (21 out of 26) were published from 2010 onwards, perhaps reflecting an increasing awareness of the importance of rational prescribing in this cohort of older patients.

The Beers criteria [11,12,13] were the most commonly used of all the tools. With the exception of the STOPP START [15] and the Holmes criteria [57], all the other tools used were developed as country-specific versions of the Beers criteria. The review demonstrates that even when the same tool was used, how the tools were applied varied across studies. For example, several studies did not apply the disease-specific part of the Beers criteria to identify PIMs for people with dementia [29, 40,41,42, 45, 47, 52] mainly due to a lack of diagnostic or prescribing information. This may have underestimated the prevalence of PIP. Three studies compared the prevalence of PIP between those with and without dementia and reported a significantly lower prevalence in the dementia group [41, 47, 52]. Prevalence rates for PIP in people with dementia may have been higher had the disease-specific tools been applied. Prevalence under-reporting was also found in a systematic review of studies using the Beers criteria to identify PIP in older people [61]. When designing a study, researchers need to consider what medication and diagnostic data they will need to collect to fully apply their chosen tool. This will reduce the risk of underestimating the prevalence of PIP. There may also be scope for reviewing how hospital, general practice and care homes record prescribing and diagnostic information, how this can be improved and whether better recording of such information would lead to improvements in prescribing.

Polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use

This review found that prevalence of polypharmacy in those with dementia (25% to 98%) is high. This range of polypharmacy prevalence is similar to that in previous studies of polypharmacy in older people with dementia [62,63,64,65,66].

The prevalence of PIP in people with dementia ranged from 13 to 74% and from 11 to 39% for people without dementia. This is despite over 20 years of research into inappropriate prescribing in older people [10, 67, 68].

We were unable to reach a conclusion as to whether the prevalence rates of PIP are significantly higher in people with dementia compared with people without cognitive impairment. Some studies reported a higher rate of PIP in those with dementia [2, 39], while some reported the opposite effect [41, 43, 47] and others reported no difference between the two groups [31, 37]. The different findings may be partly due to the different tools used, how they were applied and variations in study design.

The most commonly prescribed potentially inappropriate medications reported were sedatives and anticholinergic medications. This is despite strong evidence that these medications should be avoided because of their adverse cognitive effects in people with dementia [69,70,71,72]. Only two studies correlated the use of such medications by severity of dementia [31, 38] which is surprising given the known risks associated with their use. Future research should focus on the use of medications with strong central nervous system (CNS) effects in people with dementia and how this changes over the disease course. Oestrogen was another commonly prescribed PIM despite an increased risk of endometrial and breast cancer, and there is some evidence it may increase cognitive decline in postmenopausal women [12, 41, 73, 74].

Advantages and disadvantages of the tools

The included studies highlighted some potential advantages and disadvantages of the tools. One study identified that both the STOPP START and the Beers criteria were internationally recognised and well-validated tools, making them the preferred choice despite any potential disadvantages [35].

However, medication or diagnostic information needed to apply sections of the criteria was not always available. For example, studies using the Beers criteria, or tools adapted from them, were unable to obtain information about dose or diagnosis in patient notes which meant parts of the tools were not used [40,41,42, 47]. In addition, one study had to exclude more than half of the STOPP criteria due to a lack of availability of diagnostic and other clinical information in patient notes [5]. It may be that the STOPP START criteria would be more useful in a clinical setting than in research. It could be used to support medication reviews in the presence of the patient where the necessary clinical information needed to fully utilise the tool can be obtained. The STOPP START is one of the few tools designed to identify both overuse and underuse of medications and as such would enable a comprehensive review of a patient’s medications compared with other tools such as the Beers criteria.

Studies utilising the STOPP START criteria [15] to identify PIMs excluded the START component and therefore did not identify cases where there was under-use of medications [2, 5, 35]. Given that people with dementia may be at risk of under-treatment, including poor pain control [3, 4], it is important to consider this aspect of potentially inappropriate prescribing in both clinical and research settings.

As new evidence becomes available, the tools need regular updating but this may not always be done. The Holmes criteria [57] were found to be in need of updating. In four of the studies using the Holmes criteria [34, 38, 48, 49], one of the most commonly prescribed PIMs were acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. These medications were placed in the Never Appropriate category of the Holmes criteria [57] because at the time of the criteria’s development there was little evidence to support their use for moderate to severe dementia [48]. However, recent evidence suggests they may continue to have a positive effect in later stages of the disease [75, 76] and this has resulted in changes to clinical guidelines on use of donepezil in people with dementia [41].

One study highlighted that the Beers criteria [12] were not comprehensive enough, particularly regarding anticholinergics and sedatives [40]. Subsequent versions of the Beers criteria [13, 14] include a list of anticholinergic and sedative medications that should be avoided particularly in older people with dementia or delirium. However, this list is not as comprehensive as the tools developed specifically to identify anticholinergic medications [55, 56, 77] which were used by some of the included studies in this review [2, 32, 35, 39, 46].

In choosing an appropriate tool to identify PIP for a research study, pragmatic consideration needs to be given to its comprehensiveness, how up to date it is and whether the tool can be fully utilised given the available drug and medical history information of the cohort under investigation.

Quality of the included studies

This review found that the reporting of the studies as measured by the Hawker Tool was generally good, with most studies scoring well overall. However, most of the studies could have better reported ethical and bias considerations and discussed generalisability of their findings in more detail. Better reporting of studies is crucial to being able to judge their potential for bias and the reliability of results.

The generalisability of the findings of this review may be limited by the marked heterogeneity of the methodologies employed in the included studies, for example, the variations in which tools were used and how they were utilised and the variations in study population and settings.

Twenty-five out of the 26 included studies were observational in design, and of these, only three were prospective cohort studies [39, 45, 48] while the remaining studies collected cross-sectional or retrospective data. The benefit of a prospective design is the reduced risk of bias and confounding. However, prospective studies conducted over many years run the risk of a high rate of attrition which the authors of one study noted was a limitation of their work [39]. The only intervention study [30] utilised an uncontrolled “before and after” design which risks an overestimation of the effect of the intervention. In addition, four studies may have had low statistical power due to a small sample size of less than 150 which may have affected the reliability of their results [5, 29, 30, 33]. More robust study designs that limit the opportunity for confounding or bias are needed in this area of research. A similar observation was made in a previous review of studies using the STOPP START criteria [78].

Strengths and limitations of the review

To date, this is the first systematic review of studies using tools to identify PIP in people with dementia and was designed using robust methodology [21]. A previous literature review [79] covered a similar topic; however, it was not a rigorously conducted systematic review. In addition, this review is more up to date and includes studies published as recently as 2016.

There are several potential limitations. Two papers by the same authors were included despite the potential for some overlap of participants in the two studies [40, 41]. Although the participants in each study appeared to be distinct, it was not entirely clear whether some of the participants may have taken part in both studies; therefore, the demographic data may be slightly overestimated.

A meta-analysis on the extracted data for prevalence of, or factors associated with, PIP was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of methodology, participants, tools used and the application of those tools. There was heterogeneity of reporting data such as mean/median number of medications and prevalence of polypharmacy across the included studies. When reported in the original articles, the mean or median number of medications are presented in Table 2.

Implications for practice

This review has highlighted the need for a more standardised approach in the use of the tools that have been developed to identify PIP in older people with dementia. Tools identifying PIP cannot replace clinical judgement, and a medication identified as potentially inappropriate using such tools may subsequently be found to be appropriate following a full clinical assessment. Therefore, the use of such tools should be seen as a guide to aid clinical decision-making.

The use of more than one tool in several of the included studies suggests that current tools need to be more comprehensive to ensure that all potentially inappropriate medications are included. Consideration of whether the use of anxiolytic–hypnotic and anticholinergic medications is appropriate is particularly important given their effects on older people in general, but especially in people with dementia. As a minimum, clinicians should consider focusing on such CNS-PIP medications as a priority for deprescribing in this cohort. One of the published anticholinergic tools such as the Drug Burden Index [56] or the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale [77] may prove a useful guide to aid decision-making when reviewing a patient’s medications.

When deciding which tool to use, consideration needs to be given regarding what data will be needed to fully utilise the tool, the location of use, whether this data can be obtained and how to obtain it. In view that the tools have many differences, and none are universally applicable, two (or more) complementary tools (preferably recently updated) might be needed for a thorough assessment of PIP; using a tool which identifies both PIPs and omitted drugs would increase the clinical impact.

Future research

This review has demonstrated that rates of inappropriate prescribing and polypharmacy amongst older people with dementia are high. In particular, rates of anticholinergic and sedative medication use are high despite evidence of the risks associated with their use in people with dementia. Future research should focus on why this is the case and how the prescribing of these medications can be reduced.

As PIP is associated with the number of medications a patient is taking [5, 33, 37, 38, 41, 42, 52], future studies could focus on identifying a standardised way to present drug exposure that includes a definition of excessive polypharmacy (e.g. the use of ≥ 10 medications) and the use of concomitant medications as well as overuse or underuse of medications. Furthermore, given the known risks associated with the use of medications such as anticholinergics and sedatives in people with dementia, studies that correlate potentially inappropriate use of central nervous system medications with disease severity are needed.

Conclusions

This review found that the application of tools varied considerably. This may in part explain the variations in prevalence of PIP found across the studies. To be effective, they need to be regularly updated and may not yet be comprehensive enough to identify all potentially inappropriate medications. The review also demonstrated that despite long standing awareness of inappropriate prescribing, prevalence of PIP remains high for both older people in general and older people with dementia in particular.

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International. Improving healthcare for people with dementia: coverage, quality and costs now and in the future. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2016.pdf (2016, accessed 22 April 2018)

Andersen F, Viitanen M, Halvorsen DS, Straume B, Engstad TA (2011) Co-morbidity and drug treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. a cross sectional study of participants in the Dementia Study in Northern Norway. BMC Geriatr 11:58–64

Reynolds KS, Hanson LC, DeVellis RF, Henderson M, Steinhauser KE (2008) Disparities in pain management between cognitively intact and cognitively impaired nursing home residents. J Pain Symptom Manag 35:388–396

de Souto BP, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Vellas B, Rolland Y (2013) Potential underuse of analgesics for recognized pain in nursing home residents with dementia: a cross-sectional study. PAIN® 154:2427–2431

Parsons C, Johnston S, Mathie E et al (2012) Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people with dementia in care homes. Drugs Aging 29:143–155

Duerden M, Avery T and Payne R, Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: making it safe and sound. London: The King's Fund; https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf (2013, Accessed 7 April 2017)

Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, Doebbeling CC, Thomas J (2010) Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 8:562–570

Cahir C, Fahey T, Teeling M, Teljeur C, Feely J, Bennett K (2010) Potentially inappropriate prescribing and cost outcomes for older people: a national population study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 69:543–552

Kaufmann CP, Tremp R, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML (2014) Inappropriate prescribing: a systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70:1–11

Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC (1991) Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 151:1825–1832

Beers MH (1997) Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly: an update. Arch Intern Med 157:1531–1536

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH (2003) Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 163:2716–2724

Campanelli CM (2012) American Geriatrics Society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: the American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:616–625

Radcliff S, Yue J, Rocco G et al (2015) American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:2227–2246

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O'Mahony D (2008) STOPP (screening tool of older person’s prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 46:72–83

O'mahony D, O'sullivan D, Byrne S, O'connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P (2015) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 44:213–218

Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, Bertenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ (2007) Conflicts and concordance between measures of medication prescribing quality. Med Care 45:95–99

Chang CB, Chen JH, Wen CJ et al (2011) Potentially inappropriate medications in geriatric outpatients with polypharmacy: application of six sets of published explicit criteria. Br J Clin Pharmacol 72:482–489

O'Connor MN, Gallagher P, O'Mahony D (2012) Inappropriate prescribing. Drugs Aging 29:437–452

Blass DM, Black BS, Phillips H et al (2008) Medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23:490–496

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 349:g7647

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J (2002) Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 12:1284–1299

Ahmed N, Bestall J, Ahmedzai SH, Payne S, Clark D, Noble B (2004) Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 18:525–542

Dinç L, Gastmans C (2013) Trust in nurse–patient relationships: a literature review. Nurs Ethics 20:501–516

Herber OR, Johnston BM (2013) The role of healthcare support workers in providing palliative and end-of-life care in the community: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community 21:225–235

Oishi A, Murtagh FE (2014) The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med 28:1081–1098

Firn J, Preston N, Walshe C (2016) What are the views of hospital-based generalist palliative care professionals on what facilitates or hinders collaboration with in-patient specialist palliative care teams? A systematically constructed narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 30:240–256

Fearnley R, Boland JW (2017) Communication and support from health-care professionals to families, with dependent children, following the diagnosis of parental life-limiting illness: a systematic review. Palliat Med 31:212–222

Chan VT, Woo BK, Sewell DD et al (2009) Reduction of suboptimal prescribing and clinical outcome for dementia patients in a senior behavioral health inpatient unit. Int Psychogeriatr 21:195–199

Brunet NM, Sevilla-Sánchez D, Novellas JA et al (2014) Optimizing drug therapy in patients with advanced dementia: a patient-centered approach. Eur Geriatr Med 5:66–71

Alzner R, Bauer U, Pitzer S, Schreier MM, Osterbrink J, Iglseder B (2016) Polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medication and cognitive status in Austrian nursing home residents: results from the OSiA study. Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift (1946) 166:161–165

Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, Beer C (2012) Use of potentially harmful medications and health-related quality of life among people with dementia living in residential aged care facilities. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2:361–371

Barton C, Sklenicka J, Sayegh P, Yaffe K (2008) Contraindicated medication use among patients in a memory disorders clinic. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 6:147–152

Colloca G, Tosato M, Vetrano DL et al (2012) Inappropriate drugs in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment: results from the shelter study. PLoS One 7:e46669

Cross AJ, George J, Woodward MC et al (2016) Potentially inappropriate medications and anticholinergic burden in older people attending memory clinics in Australia. Drugs Aging 33:37–44

Epstein NU, Saykin AJ, Risacher SL, Gao S, Farlow MR, Initiative AsDN (2010) Differences in medication use in the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: analysis of baseline characteristics. Drugs Aging 27:677–686

Fiss T, Thyrian JR, Fendrich K, Berg N, Hoffmann W (2013) Cognitive impairment in primary ambulatory health care: pharmacotherapy and the use of potentially inappropriate medicine. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28:173–181

Hanlon JT, Aspinall SL, Handler SM et al (2015) Potentially suboptimal prescribing for older veteran nursing home patients with dementia. Ann Pharmacother 49:20–28

Koyama A, Steinman M, Ensrud K, Hillier TA, Yaffe K (2013) Ten-year trajectory of potentially inappropriate medications in very old women: importance of cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:258–623

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Shega JW, Rademaker A, Weintraub S (2011) Functional decline associated with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimer's Dis Other Dementias® 26:606–615

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Harris AT, Trittschuh E, Shega J, Weintraub S (2010) Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among community-dwelling elders with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24:56–63

Montastruc F, Gardette V, Cantet C et al (2013) Potentially inappropriate medication use among patients with Alzheimer disease in the REAL. FR cohort: be aware of atropinic and benzodiazepine drugs! Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:1589–1597

Nygaard H, Naik M, Ruths S, Straand J (2003) Nursing-home residents and their drug use: a comparison between mentally intact and mentally impaired residents. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 59:463–469

Oesterhus R, Aarsland D, Soennesyn H, Rongve A, Selbaek G, Kjosavik SR (2017) Potentially inappropriate medications and drug–drug interactions in home-dwelling people with mild dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 32:183–192

Raivio MM, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH (2006) Use of inappropriate medications and their prognostic significance among in-hospital and nursing home patients with and without dementia in Finland. Drugs Aging 23:333–344

Somers M, Rose E, Simmonds D, Whitelaw C, Calver J, Beer C (2010) Quality use of medicines in residential aged care. Aust Fam Physician 39:413–416

Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Kennelty KA, Gellad WF, Schulz R (2012) The impact of family caregivers on potentially inappropriate medication use in noninstitutionalized older adults with dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 10:230–241

Tjia J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK et al (2010) Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:880–888

Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Peterson D, Liu Q, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL (2014) Use of medications of questionable benefit in advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med 174:1763–1771

Toscani F, Di Giulio P, Villani D et al (2013) Treatments and prescriptions in advanced dementia patients residing in long-term care institutions and at home. J Palliat Med 16:31–37

von Renteln-Kruse W, Neumann L, Klugmann B et al (2015) Geriatric patients with cognitive impairment: patient characteristics and treatment results on a specialized ward. Dtsch Arztebl Int 112:103–112

Zuckerman IH, Hernandez JJ, Gruber-Baldini AL et al (2005) Potentially inappropriate prescribing before and after nursing home admission among patients with and without dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 3:246–254

Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA (2010) Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int 107(31–32):543

Mann E, Böhmdorfer B, Frühwald T et al (2012) Potentially inappropriate medication in geriatric patients: the Austrian consensus panel list. Wien Klin Wochenschr 124(5–6):160–169

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, Pollock BG, Culp KR (2006) The anticholinergic drug scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol 46:1481–1486

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM et al (2007) A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med 167:781–787

Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Shega JW, Hougham GW, Cox Hayley D, Dale W (2008) Integrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1306–1311

Campbell NL, Maidment I, Fox C et al (2013) The 2012 update to the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(Suppl. 1):S142–S143

Laroche M-L, Charmes J-P, Merle L (2007) Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 63:725–731

Rognstad S, Brekke M, Fetveit A, Spigset O, Wyller TB, Straand J (2009) The Norwegian General Practice (NORGEP) criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescriptions to elderly patients: a modified Delphi study. Scand J Prim Health Care 27(3):153–159

Jano E, Aparasu RR (2007) Healthcare outcomes associated with Beers’ criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 41:438–448

Àvila-Castells P, Garre-Olmo J, Calvó-Perxas L et al (2013) Drug use in patients with dementia: a register-based study in the health region of Girona (Catalonia/Spain). Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:1047–1056

Fereshtehnejad S-M, Johnell K, Eriksdotter M (2014) Anti-dementia drugs and co-medication among patients with Alzheimer’s disease: investigating real-world drug use in clinical practice using the Swedish Dementia Quality Registry (SveDem). Drugs Aging 31:215–224

Lai SW, Lin CH, Liao KF, Su LT, Sung FC, Lin CC (2012) Association between polypharmacy and dementia in older people: a population-based case–control study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 12:491–498

Onder G, Liperoti R, Foebel A et al (2013) Polypharmacy and mortality among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14:450. e7–450.e12

Vetrano DL, Tosato M, Colloca G et al (2013) Polypharmacy in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER Study. Alzheimers Dement 9:587–593

Guaraldo L, Cano FG, Damasceno GS, Rozenfeld S (2011) Inappropriate medication use among the elderly: a systematic review of administrative databases. BMC Geriatr 11(1):79–88

Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S et al (2012) Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: a systematic review. PLoS One 7:e43617

Bell JS, Mezrani C, Blacker N et al (2012) Anticholinergic and sedative medicines: prescribing considerations for people with dementia. Aust Fam Physician 41:45–49

Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID et al (2011) Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:1477–1483

Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, Barratt JD, Roughead EE (2014) Multiple anticholinergic medication use and risk of hospital admission for confusion or dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 62:1916–1922

Guthrie B, Clark SA, McCowan C (2010) The burden of psychotropic drug prescribingin people with dementia: a population database study. Age Ageing 39:637–642

Yaffe K, Sawaya G, Lieberburg I, Grady D (1998) Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women: effects on cognitive function and dementia. JAMA 279:688–695

Kang JH, Weuve J, Grodstein F (2004) Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cognitive decline in community-dwelling aging women. Neurology 63:101–107

Sabbagh M, Cummings J (2011) Progressive cholinergic decline in Alzheimer’s disease: consideration for treatment with donepezil 23 mg in patients with moderate to severe symptomatology. BMC Neurol 11:21

Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J et al (2012) Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 366:893–903

Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, Maidment I and Fox C (2008) Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. 4(3): 311–320

Hill-Taylor B, Sketris I, Hayden J, Byrne S, O'sullivan D, Christie R (2013) Application of the STOPP/START criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact. J Clin Pharm Ther 38:360–372

Johnell K (2015) Inappropriate drug use in people with cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. Curr Clin Pharmacol 10:178–184

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steph Jesper, librarian, University of Hull, for her assistance with the search strategy.

Funding

Deborah Hukins was funded by a PhD scholarship from the University of Hull.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualised the study. DH performed the search with support from JWB. DH and JWB screened the articles with UM as a 3rd reviewer. DH drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and helped finalise the article for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PNG 1 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hukins, D., Macleod, U. & Boland, J.W. Identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people with dementia: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 467–481 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-02612-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-02612-x