Abstract

Objective

To compare characteristics and incidence of discontinuation of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients starting ropinirole or pramipexole in clinical practice with data from randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs).

Methods

Included in the retrospective clinical-practice cohort were first-time users of ropinirole or pramipexole diagnosed with PD before 2005. Baseline characteristics and incidence of discontinuation were compared between the clinical-practice cohort and RCTs. Treatment discontinuation was defined as more than 180 days between two refills of ropinirole or pramipexole. The incidence of discontinuation in RCTs was based on the reported rate of discontinuation for any cause.

Results

Included were 45 patients who started with ropinirole and 59 patients who started with pramipexole. Treatment was discontinued within 3 years in 51% (ropinirole) and 60% (pramipexole) of the patients. Ten RCTs with ropinirole and 12 with pramipexole were identified. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the clinical-practice cohort and RCTs. RCTs reported discontinuation rates comparable with those at the same timepoint in the clinical practice until 1 year of follow-up.

Conclusion

This study shows that the overall incidence of discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole between the patients in our clinical-practice cohort and patients in the RCTs was comparable for the short term. However for the long term, discontinuation in practice is possibly higher.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ropinirole and pramipexole, two non-ergoline dopamine agonists with high binding characteristics for the dopamine D2 receptor and with a preferential affinity to the dopamine D3 receptor subgroup, were introduced during the past 10 years for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Compared with levodopa, dopamine agonists have been associated with a reduced risk of developing dyskinesias [1, 2]. There are also indications—although arguable—that ropinirole and pramipexole might slow disease progression [3–5]. Therefore, it could be beneficial to continue (initial) non-ergoline dopamine agonist therapy as long as possible.

Clinical trials frequently do not mirror daily practice [6]. In trials, the effects of drugs are examined for a limited period of time, under well-controlled conditions and in a homogeneous and highly selected group of patients. This hampers generalisation of clinical trial data with regard to efficacy, tolerability and safety to daily clinical practice. Observational research within the setting of daily clinical practice can complement the results of randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs). A useful measure of effectiveness in observational studies, which encompasses both efficacy and tolerability, is the incidence of drug discontinuation.

The objective of this study was to compare patient characteristics and the incidence of discontinuation of ropinirole or pramipexole between a clinical-practice cohort with PD and data from RCTs.

Methods

Setting and study population

Clinical-practice cohort

The setting of this retrospective cohort study was the neurology department of a large teaching hospital in Enschede, The Netherlands. Included were outpatients diagnosed with PD before 2005 who received ropinirole or pramipexole for the first time. Prescription data were retrieved from community pharmacies after obtaining the patients’ informed consent. The date of first prescription of ropinirole and pramipexole was defined as the index date. To ascertain first-time use, patients were required to have at least 180 days of prescription history for any medicine before the index date. Patients were excluded if there were prescription data for fewer than 180 days for any medicine after the index date. The same patient could be included two times: one time for ropinirole and one time for pramipexole treatment.

RCTs

In order to identify published RCTs with ropinirole or pramipexole treatment in PD patients, we performed a Pubmed search with the keywords ‘ropinirole’ or ‘pramipexole’ and ‘Parkinson’s disease’ and the limits ‘randomized controlled trial’, ‘English language’ and ‘humans’. Articles published until March 2007 that matched all criteria were included. All references in selected articles were screened and included when of interest. A cited reference search in Web of Science was done in order to identify missing articles. Finally, we performed a search in the Cochrane central register of controlled trials.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the clinical-practice cohort were recorded from the medical chart.

For each dopamine agonist, we pooled all RCTs that included patients with early PD as well as patients already using levodopa. The baseline characteristics of those patients were weighted for the number of patients.

Incidence of discontinuation

The patients in the clinical-practice cohort were considered to have discontinued treatment when more than 180 days elapsed between two consecutive pharmacy refills of ropinirole or pramipexole. Patients who persisted with therapy to the end of their observation time were censored on the last day of their follow-up. Consequently, patients who may have moved to another place or died during follow-up were censored on the last day of their follow-up. Cumulative hazards of discontinuation were plotted against the time of follow-up.

The incidence of discontinuation in the RCTs was based on the reported rate of discontinuation for any cause and was plotted per trial against the time of follow-up. A Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the incidence of discontinuation between the clinical-practice and RCT cohorts at the timepoints 1, 2, 3 and 5 years of follow-up for ropinirole or 1, 2 and 4 years of follow-up for pramipexole.

In the clinical-practice cohort, a stratified Cox regression analysis was performed to investigate whether there was a difference in discontinuation between patients who used levodopa at baseline and those not using levodopa at baseline.

Furthermore, an analysis was conducted to determine whether other anti-parkinsonian treatment was started after discontinuation of ropinirole or pramipexole (within an interval of ± 90 days).

Results

Characteristics

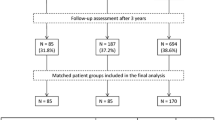

From the clinical-practice cohort of 236 patients with PD, we identified 45 patients who started with ropinirole and 59 patients who started with pramipexole between 1998 and 2005 and who met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Fourteen patients were included twice: once for ropinirole and once for pramipexole treatment. From the literature, ten RCTs with ropinirole met the criteria, of which one was a 6-month extension trial. Twelve RCTs with pramipexole were identified, of which one was an extension trial.

The baseline characteristics in the clinical-practice cohort and the RCTs are summarised in Table 1. The median follow-up in the clinical-practice cohort was 2.0 years for the ropinirole users and 1.6 years for pramipexole users. The follow-up time in the RCTs ranged from 12 weeks to 5 years for ropinirole, and from 9 weeks to 4 years for pramipexole. Three RCTs with ropinirole and two trials with pramipexole had a follow-up period that was longer than 1 year.

Incidence of discontinuation

In the clinical-practice cohort, 3 years after the initiation of dopamine agonist therapy, 51% had discontinued ropinirole and 60% had discontinued pramipexole (Fig. 2). There was no statistically significant difference in discontinuation of ropinirole or pramipexole treatment between patients who used levodopa at baseline and those not using levodopa at baseline. In the RCTs, the incidence of discontinuation ranged from 7–53% for ropinirole and from 0–45% for pramipexole, depending on the duration of follow-up in the RCT (Fig. 2). As seen in Fig. 2, all five studies lasting more than 1 year were below the discontinuation curve from the clinical-practice cohort. Indeed, the discontinuation rates in the RCTs were not significantly different from those at the same timepoint in the clinical practice cohort until 1 year of follow-up for pramipexole. However, there was no statistically significant difference until 5 years of follow-up for ropinirole.

Cumulative hazard of discontinuation in the clinical-practice cohort (solid lines, with numbers of patients at risk below) and the proportion of discontinuation in RCTs in patients with Parkinson’s disease. a Ropinirole: ♦ [17], ▪ [18], ▴ [19], x [20], Δ [21], ● [22], + [1], ○ [23], - [24], ◊ [3]. b Pramipexole: — [25], - [26], ◊ [27], x [28], Δ [29], ● [30], ○ [31], ♦ [32], □ [33], + [34], ▴ [2], ▪ [35]

In the clinical-practice cohort, two patients (8%) who discontinued ropinirole treatment started with amantadine and four patients (16%) started with an ergoline dopamine agonist. One of the patients (3%) who discontinued pramipexole treatment started with amantadine and one patient (3%) with an ergoline dopamine agonist.

Discussion

The main observation from this retrospective clinical-practice cohort study is that the incidence of discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole in our cohort was comparable to that reported in RCTs for the short term. However, for the long term, discontinuation in daily clinical practice is possibly higher. This suggests that for these dopamine agonists, only short-term discontinuation rates reported in RCTs can be extrapolated to daily clinical practice.

All five long-term trials with a follow-up time extending over 1 year differed from the short-term trials in several ways. Firstly, only patients with early PD not using levodopa were included at baseline. Secondly, in contrast with most of the short-term trials, levodopa rescue therapy was allowed in the long-term trials. These facts may have reduced the incidence of discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole in the long-term trials. In daily clinical practice, levodopa co-medication is also commonly used. However, we hypothesize that in situations where rescue medication is needed, clinicians tend more towards discontinuation of dopamine agonist treatment in daily clinical practice than in RCTs.

In addition to similar short-term discontinuation rates, our patients also had similar baseline characteristics as those reported in the RCTs. Our patients did differ from those included in the RCTs in two ways. Firstly, some of our patients used antipsychotics while starting with ropinirole (9%) or pramipexole (19%), while antipsychotics users were excluded in most of the RCTs. In daily clinical practice, antipsychotic use in patients with PD is common [7, 8]. Secondly, the mean dose of ropinirole or pramipexole used was lower in our cohort than the maximum dose in the RCTs. This is explained by the fact that we calculated the mean dose over the entire follow-up, including the titration phase. The dose reported in the RCTs is the maximum dose at the end of follow-up, which is likely higher than the mean dose. We have no indication that a larger number of patients in the clinical-practice cohort would have led to other estimates of baseline demographic items.

In another retrospective cohort study with PD patients of 80 years or older, 69% discontinued treatment with ropinirole and 60% with pramipexole within the first 6 months [9]. In several other therapeutic areas, there have been repeated examples of clear differences in patient characteristics between RCTs and daily clinical practice [10, 11]. Selective prescribing frequently occurs in daily clinical practice [12, 13]. Differences in patient characteristics may influence the frequency of benefit and harm of therapy and thereby have important consequences for assessing the therapeutic effects of a (relatively) new drug in daily clinical practice. In this light, the similarity of patient characteristics between RCTs and our clinical-practice cohort is rather surprising but comforting, suggesting that RCT data with pramipexole and ropinirole may be generalised to daily clinical practice.

It would be clinically interesting to have knowledge about which patients benefit from pharmacotherapy in daily practice. In this study, we performed an additional analysis to determine whether patient characteristics, including antipsychotic or antidepressant use, were associated with discontinuation of ropinirole or pramipexole using Cox regression analysis. No statistical determinants for discontinuation were detected. However, genetic determinants for discontinuation should be investigated in the future [14].

The strength of the present study is the relatively long follow-up of patients in the clinical-practice cohort and the comparison with data from RCTs. However, there are several possible limitations to our study. Firstly, we were not able to retrieve the precise reasons for discontinuation of ropinirole or pramipexole in our study. A major reason for early discontinuation could be adverse effects [15]. Lack of efficacy also leads to early discontinuation. PD patients often report a poor therapy response because they expect an improvement in tremor, which occurs in only about half of the cases [15]. Secondly, our definition of discontinuation could be discussed. It is known that the refill persistence is influenced by the maximum allowed treatment gap [16], resulting in under- or overestimation of the incidence of discontinuation. Discontinuation was defined as patients for whom more than 180 days elapsed between two consecutive pharmacy refills of ropinirole or pramipexole, while the maximum length of prescription in the Netherlands is 90 days. In our clinical-practice cohort, the mean refill length of a prescription was 50 days for ropinirole and 47 days for pramipexole. Therefore, we feel that our results do not represent an overestimation of the true incidence of discontinuation. Finally, we included outpatients from only one hospital. Therefore, the results could have been biased by the prescribing patterns of a few clinicians.

In conclusion, this study shows that the overall characteristics and incidence of discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole between the patients in our clinical-practice cohort and patients in the RCTs were comparable for the short term. For the long term, discontinuation in practice is possibly higher. More research is needed to investigate the reasons and determinants of discontinuation in daily clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- RCTs:

-

Randomised controlled clinical trials

References

Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Korczyn AD, De Deyn PP, Clarke CE, Lang AE (2000) A five-year study of the incidence of dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were treated with ropinirole or levodopa. 056 Study Group. N Engl J Med 342:1484–1491

Holloway RG, Shoulson I, Fahn S, Kieburtz K, Lang A, Marek K et al (2004) Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a 4-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Neurol 61:1044–1053

Whone AL, Watts RL, Stoessl AJ, Davis M, Reske S, Nahmias C et al (2003) Slower progression of Parkinson’s disease with ropinirole versus levodopa: the REAL-PET study. Ann Neurol 54:93–101

The Parkinson Study Group (2002) Dopamine transporter brain imaging to assess the effects of pramipexole vs levodopa on Parkinson disease progression. JAMA 287:1653–1661

Joyce JN, Millan MJ (2007) Dopamine D3 receptor agonists for protection and repair in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 7:100–105

Leufkens HG, Urquhart J (1994) Variability in patterns of drug usage. J Pharm Pharmacol 46(Suppl 1):433–437

van de Vijver DA, Roos RA, Jansen PA, Porsius AJ, de Boer A (2002) Antipsychotics and Parkinson’s disease: association with disease and drug choice during the first 5 years of antiparkinsonian drug treatment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58:157–161

Marras C, Kopp A, Qiu F, Lang AE, Sykora K, Shulman KI et al (2007) Antipsychotic use in older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 22:319–323

Shulman LM, Minagar A, Rabinstein A, Weiner WJ (2000) The use of dopamine agonists in very elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 15:664–668

Wieringa NF, de Graeff PA, van der Werf GT, Vos R (1999) Cardiovascular drugs: discrepancies in demographics between pre- and post-registration use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 55:537–544

Wieringa NF, Vos R, van der Werf GT, van der Veen WJ, de Graeff PA (2000) Co-morbidity of ‘clinical trial’ versus ‘real-world’ patients using cardiovascular drugs. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 9:569–579

Egberts AC, Lenderink AW, de Koning FH, Leufkens HG (1997) Channeling of three newly introduced antidepressants to patients not responding satisfactorily to previous treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 17:149–155

Movig KL, Egberts AC, Lenderink AW, Leufkens HG (2000) Selective prescribing of spasmolytics. Ann Pharmacother 34:716–720

Arbouw ME, van Vugt JP, Egberts TC, Guchelaar HJ (2007) Pharmacogenetics of antiparkinsonian drug treatment: a systematic review. Pharmacogenomics 8:159–176

Grosset KA, Reid JL, Grosset DG (2005) Medicine-taking behavior: implications of suboptimal compliance in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 20:1397–1404

Van Wijk BL, Klungel OH, Heerdink ER, de Boer A (2006) Refill persistence with chronic medication assessed from a pharmacy database was influenced by method of calculation. J Clin Epidemiol 59:11–17

Rascol O, Lees AJ, Senard JM, Pirtosek Z, Montastruc JL, Fuell D (1996) Ropinirole in the treatment of levodopa-induced motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 19:234–245

Adler CH, Sethi KD, Hauser RA, Davis TL, Hammerstad JP, Bertoni J et al (1997) Ropinirole for the treatment of early Parkinson’s disease. The Ropinirole Study Group. Neurology 49:393–399

Brooks DJ, Abbott RJ, Lees AJ, Martignoni E, Philcox DV, Rascol O et al (1998) A placebo-controlled evaluation of ropinirole, a novel D2 agonist, as sole dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 21:101–107

Sethi KD, O’Brien CF, Hammerstad JP, Adler CH, Davis TL, Taylor RL et al (1998) Ropinirole for the treatment of early Parkinson disease: a 12-month experience. Ropinirole Study Group. Arch Neurol 55:1211–1216

Lieberman A, Olanow CW, Sethi K, Swanson P, Waters CH, Fahn S et al (1998) A multicenter trial of ropinirole as adjunct treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Ropinirole Study Group. Neurology 51:1057–1062

Korczyn AD, Brunt ER, Larsen JP, Nagy Z, Poewe WH, Ruggieri S (1999) A 3-year randomized trial of ropinirole and bromocriptine in early Parkinson’s disease. The 053 Study Group. Neurology 53:364–370

Brunt ER, Brooks DJ, Korczyn AD, Montastruc JL, Stocchi F (2002) A six-month multicentre, double-blind, bromocriptine-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of ropinirole in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease not optimally controlled by L-dopa. J Neural Transm 109:489–502

Im JH, Ha JH, Cho IS, Lee MC (2003) Ropinirole as an adjunct to levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: a 16-week bromocriptine controlled study. J Neurol 250:90–96

Hubble JP, Koller WC, Cutler NR, Sramek JJ, Friedman J, Goetz C et al (1995) Pramipexole in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 18:338–347

Lieberman A, Ranhosky A, Korts D (1997) Clinical evaluation of pramipexole in advanced Parkinson’s disease: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Neurology 49:162–168

Shannon KM, Bennett JP Jr, Friedman JH (1997) Efficacy of pramipexole, a novel dopamine agonist, as monotherapy in mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. The Pramipexole Study Group. Neurology 49:724–728

Guttman M (1997) Double-blind comparison of pramipexole and bromocriptine treatment with placebo in advanced Parkinson’s disease. International Pramipexole-Bromocriptine Study Group. Neurology 49:1060–1065

Pinter MM, Pogarell O, Oertel WH (1999) Efficacy, safety, and tolerance of the non-ergoline dopamine agonist pramipexole in the treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease: a double blind, placebo controlled, randomised, multicentre study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66:436–441

The Parkinson Study Group (2000) Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 284:1931–1938

Pogarell O, Gasser T, van Hilten JJ, Spieker S, Pollentier S, Meier D et al (2002) Pramipexole in patients with Parkinson’s disease and marked drug resistant tremor: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 72:713–720

Wong KS, Lu CS, Shan DE, Yang CC, Tsoi TH, Mok V (2003) Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of pramipexole in untreated and levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 216:81–87

Navan P, Findley LJ, Jeffs JA, Pearce RK, Bain PG (2003) Randomized, double-blind, 3-month parallel study of the effects of pramipexole, pergolide, and placebo on Parkinsonian tremor. Mov Disord 18:1324–1331

Mizuno Y, Yanagisawa N, Kuno S, Yamamoto M, Hasegawa K, Origasa H et al (2003) Randomized, double-blind study of pramipexole with placebo and bromocriptine in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 18:1149–1156

Moller JC, Oertel WH, Koster J, Pezzoli G, Provinciali L (2005) Long-term efficacy and safety of pramipexole in advanced Parkinson’s disease: results from a European multicenter trial. Mov Disord 20:602–610

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all community pharmacists who contributed to this study.

Competing interests

Jeroen van Vugt’s salary is fully covered by Medisch Spectrum Twente. He has received consultancy and speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharma, Teva Pharma and ApotheekZorg. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Arbouw, M.E.L., Movig, K.L.L., Guchelaar, HJ. et al. Discontinuation of ropinirole and pramipexole in patients with Parkinson’s disease: clinical practice versus clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 64, 1021–1026 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0518-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0518-2