Abstract

Objective

Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed drugs used by children. Excessive and irrational use of antibiotic drugs is a world-wide concern. We performed a drug utilization study describing the patterns of antibiotic use in children aged 0–19 years between 1999 and 2005 in the Netherlands.

Methods

We used IADB.nl, a database with pharmacy drug dispensing data covering a population of 500,000 people and investigated all prescriptions of oral antibiotic drugs (ATC J01) for children ≤19 years between 1999 and 2005.

Results

The total number of antibiotic prescriptions per 1000 children per year ranged from 282 in 2004 to 307 in 2001 and did not change between years during the study period in a clinically relevant way. The prevalence of receiving at least one prescription varied between 17.8% in 2004 and 19.3% in 2001. Amoxicillin was the most frequently prescribed drug (46.4% of all antibiotic prescriptions in 1999 and 43.2% in 2005). Between 1999 and 2005 there was a shift from the small-spectrum phenethicillin, a penicillin preparation [ratio 2005/1999 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72–0.81], to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (ratio 2005/1999 1.70; 95% CI 1.61–1.79) and from the old macrolide erythromycin (ratio 2005/1999 0.35; 95% CI 0.32–0.39) to the new macrolide antibiotic azithromycin (ratio 2005/1999 1.78; 95% CI 1.65–1.92).

Conclusion

The use of antibiotic drugs in treating children in the Netherlands is comparable to that in other northern European countries. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were prescribed more frequently than recommended by the guidelines and increased during our study period. Initiatives to improve guideline-directed antibiotic prescribing are strongly recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed drugs for children. A Dutch study reported that 21% of all children registered in a prescription database used at least one antibiotic drug in 1998 [1].

Excessive and irrational use of antibiotic drugs is a world-wide concern because of the development of bacterial resistance [2, 3]. Many antibiotic drugs are prescribed for respiratory tract infections even though these infections are known to be predominantly viral [4]. A Dutch epidemiological case-control study found that viruses were detected in 58% of patients with acute respiratory tract infections [5]. In a study investigating pharyngitis in children, researchers were unable to isolate bacteria from their throats of 74% of the children studied, making antibiotic treatment of this group unnecessary [6].

The Netherlands healthcare profession has a reputation for showing restraint in prescribing antibiotics. Two drug utilization studies based on national administrative data have confirmed this—relative to other European countries, the Netherlands prescribes the lowest amount of antibiotic drugs. [2, 7, 8].

This being said, little is known about antibiotic use in Dutch children. A national survey among Dutch general practitioners (GPs) in 1987 and 2001 concluded that the number of prescriptions written for broad-spectrum antibiotics prescriptions based on inappropriate diagnoses in children had increased [9]. Another study examining the treatment of respiratory tract infections reported that antibiotic drugs were prescribed in 35% of the episodes in children aged 0–5 years [10].

These studies demonstrate the need for further investigation into how antibiotic drug prescribing for Dutch children corresponds to evidence-based medicine in order to motivate improvements in prescribing. To this end, we performed a drug utilization study of antibiotic use in children aged 0–19 years from 1999 till 2005, investigating prevailing patterns in prescribing specific, frequently prescribed antibiotics as well as relating these patterns to the Dutch guidelines.

Methods

The data in this study are derived from IADB.nl (http://www.IADB.nl), a database containing pharmacy dispensing data from the Netherlands. IADB.nl covers a population of approximately 500,000 people and is representative of the Dutch population in terms of drug use. The percentage of children aged 0–19 in the database was stable in the study period (1999–2005) and varied from 22.8 to 23.2%.

The data assembled in IADB.nl are derived from 55 community pharmacies. Each prescription filled by these pharmacies, whether prescribed by GPs or specialist, is included in the database, regardless of reimbursement status. Dutch patients mainly obtain their drugs from their own local pharmacy, so the medication histories in IADB.nl are quite complete.

In this study we investigated all prescriptions of systemic antibiotic drugs [Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) classification-code J01 [11]) prescribed between 1999 and 2005 for children under the age of 20.

In the Netherlands, pharmacies deliver precisely the number of tablets prescribed for an antibiotic treatment course; if necessary, packages are opened and the exact number of tablets prescribed are delivered to the patient. An antibiotic is supplied for a maximum of 14 days. Taking these two facts into account, we assumed that one prescription represents one course of antibiotic drug.

We also determined the number of prescriptions per 1000 children per month and per year.

The yearly prevalence of antibiotic use was defined as the percentage of children who received at least one prescription per year. In order to compare the use of specific antibiotic drugs in1999 to that in 2005 we calculated the proportion of those antibiotics prescribed from among the total number of antibiotic prescriptions in both years. We also calculated the ratio of the number of prescriptions per 1000 children in 2005 compared to 1999 (ratio 2005/1999) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). These calculations were stratified for different age categories (0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19) and sex.

The numbers of the whole population used were based on general population statistics, using figures from Statistics Netherlands. We used the program Microsoft Excel ver. 2003 to analyze the results.

The guidelines used are the Standards of the Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG [12]) and the local ‘Groninger Formularium’ (GF [13]) developed by GPs and pharmacists. The latter guideline covers the main part of the population studied.

Results

We found that 234,891 prescriptions of systemic antibiotic drugs had been prescribed from 1999 to 2005 for children aged ≤19 years. The number of prescriptions per 1000 children per year ranged from 282 in 2004 to 307 in 2001 and did not change between years in a clinically relevant way. The yearly prevalence of antibiotic use in children varied between 17.8% in 2004 and 19.3% in 2001.

The monthly number of prescriptions per 1000 children fluctuated from 17 (August 2000) to 40 (December 2004), showing a peak in the winter months and a nadir in the summer months.

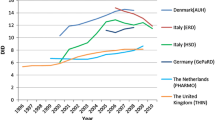

Amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, clarithromycin, phenethicillin, trimethoprim, cotrimoxazole (sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim), erythromycin, doxycyclin, nitrofurantoin, azithromycin and flucloxacillin were the most frequenly prescribed antibiotics (Fig. 1), with amoxicillin being prescribed more frequently than any of the other antibiotic drugs. The use of azithromycin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, flucloxacillin, clarithromycin and nitrofurantoin increased between 1999 and 2005 (Table 1), whereas the use of erythromycin, trimethoprim, phenethicillin, doxycycline, cotrimoxazol and amoxicillin decreased.

Figure 2 shows the increase and decrease in the monthly numbers of prescriptions per 1000 between 1999 and 2005. The use of azithromycin, amoxicillin, erythromycin, clarithromycin and doxycyclin shows peaks around the winter months. Flucloxacillin has a different pattern with peaks around August/September in 2002 and subsequent years.

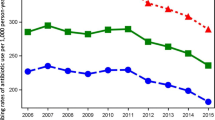

There appears to be a difference between age categories and sex in the year-prevalence of children receiving systemic antibiotics. The mean prevalence during the 7-year study period was 29.0% in the age group 0–4 years, 19.6% in the age group 5–9 years, 10.4% in the 10- to 14-year-old group and 15.1% in the 15- to 19-year-old group. In terms of gender, 17.3% of the boys and 19.9% of the girls received at least one prescription per year. Although there were some differences in the specific types of antibiotic drugs (i.e. no doxycyclin in the youngest two age groups and more drugs for urine tract infections in the oldest age group), the trends in increased and decreased prescribing in the period 1999 to 2005 remained the same in all age categories, with one exception—trimethoprim. There was a rapid decrease in the prescribing of this antibiotic in the two younger age groups compared to the two elder groups, as shown in Fig. 3. The use of trimethoprim in the age groups 0–4 years and 5–9 years decreased in the second half of 2004, and the use in the age groups 10–14 years and 15–19 years remained approximately at the same level.

Discussion

Main results

Between 1999 and 2005 the yearly prevalence of antibiotic use in children varied from 17.8 to 19.3%. The amount of antibiotic prescriptions for children calculated on a monthly basis fluctuated each year, with a peak around the winter months. Although the total number of antibiotic prescriptions per year did not change between 1999 and 2005, we did observe a shift in prescribing patterns. The prescribing of amoxicillin, the small-spectrum phenethicillin, which is a penicillin preparation, and the older macrolide erythromycin decreased, while the prescribing of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and the new macrolides azithromycin and clarithromycin increased.

The use of flucloxacillin also showed an increasing trend, especially during the months of August and September. Trimethoprim was used less by the two younger age groups. There was a general trend for antibiotic drug use to be the highest in the youngest age group (0–4 years).

Literature comparison

An Italian study of 1998, which concentrated on children aged 0–15 years, showed that 46.4% of the children studied received at least one antibiotic prescription in that year [14]. In Scotland in 1999/2000, the prevalence of antibiotic use among 0- to 16-year olds was estimated at 14.2% [15]. In a Danish study that was based on a prescription database, the prevalence of antibiotic use was 29.0% in a group of 0- to 15-year olds. When we compare our data to those reported in these studies, the prevalence of prescribing antibiotics to children ≤19 years in the Netherlands is lower than that in Italy, slightly lower than that in Denmark, but higher than that in Scotland.

The study by Otters et al. is a cross-sectional study based on the National GP Survey and restricted to 1987 and 2001 [9]. Data were presented for children aged 0–17 years, and the yearly number of antibiotic prescriptions per 1000 children was determined. In 2001, this number was smaller than what we found in 2001 (232 vs. 307). Possible explanations for this difference could be the dissimilar age groups or the fact that the origin of the data is not the same—that is to say, GPs in the National Survey were aware of participation, which may have influenced their prescribing behaviour. However, our study shows that the trend described by the Otters study (an increase in the number of broad-spectrum antibiotic prescriptions) continued between 2001 and 2005.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic drugs in our study were amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and clarithromycin. This is comparable to the data obtained in the National Survey from 2001 [9]. In Germany and Denmark, the small-spectrum penicillin known as penicillin V was prescribed more often for children than the broad-spectrum penicillins [16, 17]. In Italy, cephalosporins and macrolides were prescribed the most [14] and in Scotland, amoxicillin, erythromycin and phenoxymethylpenicillin were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics [15]. It would appear that each country has its own preferences in terms of antibiotic drugs.

In our study, the prevalence of antibiotic use was highest in the youngest age group, and the lowest prevalence of users was found in the group of 10- to 14-year olds. In the National Survey, a similar distribution of antibiotic use was found [9]. Studies from Italy and Denmark used different age groups. Consequently, a direct comparison was not possible [14, 17].

Seasonal variation

The fluctuations during the year in the number of prescriptions per month peaking in the winter period and showing a nadir in the summer is similar to the results of a European study on adults [8] and possibly indicates that most antibiotic drugs are prescribed for respiratory infections. Figure 2 shows precisely this pattern for drugs used in treating respiratory infections (azithromycin, amoxicillin, erythromycin, clarithromycin and doxycyclin). In contrast, trimethoprim (Fig. 3), which is used for urinary tract infections, does not show this kind of fluctuation.

The August and September peaks of flucloxacillin use (Fig. 2) can be explained by an increase in the number of impetigo cases in children in the Netherlands, which usually occurs after the summer holiday when school starts again. This phenomenon is described in a study by GPs [18].

Changes over time

The changes in the prescribing patterns between 1999 and 2005, which show an evolution in prescribing behaviour from a preference for small-spectrum penicillin to one for amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and from older to newer macrolides, have also been described in other Dutch studies [9, 19]. This shift could be linked to a number of circumstances. It is possible that the reports on increasing antibiotic resistance encouraged physicians to choose a broader and more safe approach to prescribing. The decrease in the use of erythromycin may be attributed to the fact that its use is associated with more side effects, worse pharmacokinetic properties and increased interactions with other drugs, in comparison to other macrolides. Azithromycin has the additional advantage of requiring a shorter course and having a more convenient dosage system as a liquid formulation. Clarithromycin is currently available in straws, which allows the child to take the drug by sucking it through the straw; this is a clever solution which may also be preferred by the prescribing physician.

The decreased use of trimethoprim in the second half of 2004, especially in younger age groups, can be explained by discontinuation of the product Monotrim, the only liquid formulation of trimethoprim available in the Netherlands [20]. There is an alternative in a pharmacy-based formulation, however, this takes some time to prepare. According to our results, most physicians choose to prescribe a different antibiotic. Nitrofurantoin may be an alternative to trimethoprim, but as this is not available as a liquid formulation either, the physicians may prefer amoxicillin with clavulanic acid or cotrimoxazole as an alternative for these age groups.

Comparison to Dutch guidelines

Acute respiratory infections and otitis media are the most frequently occurring infections in children. Data from the National Survey showed that in 2001 the yearly incidence of these two types of infections was 94.8 and 61.2 per 1000 children, respectively [21]. For a respiratory infection, both Dutch guidelines, the NHG and GF, recommend prescribing small-spectrum phenethicillin only in the case of a secondary bacterial infection. For otitis media, the preferred drug is amoxicillin.

Before starting treatment, it is advised to wait for 3 days to see if there’s no improvement—except when the patient is younger than 6 months. In case of a penicillin allergy, the second choice for both indications is clarithromycin [12, 13]. The large number of prescriptions for amoxicillin in this study (137.9/1000 in 2001) compared to those for phenethicillin (17.9/1000 in 2001), which are relatively few, is not in accordance with the indications for prevalence, suggesting that respiratory tract infections are possibly not treated with the preferred drug. It also appears that the guidelines' recommendation to pursue a restrained policy towards antibiotic prescribing is not being followed.

Accordingly, we conclude that the prescribing patterns in terms of prescribing antibiotic drugs for Dutch children ≤ 19 years old is not in agreement with the guidelines.

Limitations to the study

In this study the medical indications that motivated the physician to prescribe the drugs were not known as this information is generally not given to the pharmacy by the physician. The prescriptions used here were only dispensing data, so we did not know whether the patient actually did use the medication at home. Our data are merely an indication of how antibiotics are prescribed and used.

The prophylactic use of antibiotics, the prolongation of a course or the switch to another drug within a course because of allergy or side effects were all counted as separate prescriptions, even though they are actually part of one episode of use. Of all prescriptions, 85% were not followed by another antibiotic prescription within 1 month. Of the other 15%, some prescriptions may have belonged to the same clinical episode, which would suggest that we may have overestimated the number of antibiotic courses.

Over-the-counter medication is not included in our database. However, as antibiotic drugs are not allowed to be sold over-the-counter in the Netherlands, this does not represent a significant problem in our study.

Recommendations

The results of this study reveal that antibiotic prescribing for children in the Netherlands is far from optimal, which is similar to the situation in other countries.

Different ways have been investigated to improve guideline-directed prescribing of antibiotic drugs in children. One approach is to better educate the parents in antibiotic use, including explanations during visits to the doctor with the explicit aim of decreasing unnecessary prescribing [22–24]. Physicians could also be trained more thoroughly in this area. A strategy implemented in the UK—called ‘delayed prescribing’ (i.e. a required delay of a few days before starting an antibiotic course)—has reduced the prescribing rates for antibiotic drugs without causing the number of hospital admissions due to complications to increase [25–27]. The Dutch guidelines already have recommended following this strategy for otitis media [12]. The development of a clinical decision rule for respiratory infections can reduce inappropriate prescribing of antibiotic drugs [6]. A similar decision rule has been developed in public hospitals in Brazil, where they look at the symptoms to separate viral and bacterial respiratory infections, thereby preventing 41–55% of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Conclusion

On the basis of the results reported here, it would appear that the image of the Netherlands being a country with a restrained policy towards prescribing antibiotic drugs is not entirely applicable when it concerns children. Not only were broad-spectrum antibiotic drugs prescribed more frequently than recommended by the guidelines, but it also appears that a shift took place to broader prescribing between the years 1999 and 2005. This is an undesirable development as it could contribute to antibiotic resistance.

We found that the choice of drugs can be influenced by events such as the unavailability of the drug as a liquid formulation (thrimethoprim) or the increased occurrence of a specific indication (impetigo and flucloxacillin).

Our results demonstrate that an improvement of guideline-directed antibiotic prescribing is needed in the Netherlands.

References

Schirm E, van den Berg P, Gebben H, Sauer P, De Jong-van den Berg LTW (2000) Drug use of children in the community assessed through pharmacy dispensing data. Br J Clin Pharmacol 50(5):473–478

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M (2005) Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365(9459):579–587

Jacobs MR, Dagan R (2004) Antimicrobial resistance among pediatric respiratory tract infections: clinical challenges. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 15(1):5–20

Nasrin D, Collignon PJ, Roberts L, Wilson EJ, Pilotto LS, Douglas RM (2002) Effect of beta lactam antibiotic use in children on pneumococcal resistance to penicillin: prospective cohort study. Br Med J 324(7328):28–30

van Gageldonk Lafeber AB, Heijnen ML, Bartelds AI, Peters MF, van der Plas SM, Wilbrink B (2005) A case-control study of acute respiratory tract infection in general practice patients in The Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis 41(4):490–497

Smeesters PR, Campos DJ, Van Melderen L, de Aguiar E, Vanderpas J, Vergison A (2006) Pharyngitis in low-resources settings: a pragmatic clinical approach to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. Pediatrics 118(6):e1607–e1611

Cars O, Molstad S, Melander A (2001) Variation in antibiotic use in the European Union. Lancet 357(9271):1851–1853

Elseviers MM, Ferech M, Vander Stichele RH, Goossens H (2007) Antibiotic use in ambulatory care in Europe (ESAC data 1997–2002): trends, regional differences and seasonal fluctuations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(1):115–123

Otters HB, van der Wouden JC, Schellevis FG, van Suijlekom Smit LW, Koes BW (2004) Trends in prescribing antibiotics for children in Dutch general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother 53(2):361–366

Jansen AG, Sanders EA, Schilder AG, Hoes AW, de Jong VF, Hak E (2006) Primary care management of respiratory tract infections in Dutch preschool children. Scand J Prim Health Care 24(4):231–236

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistic Methodology (2002) Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistic Methodology, Oslo

Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (2007) NHG-standaarden acute keelpijn, acuut hoesten, otitis media bij kinderen. NHG, the Netherlands

Groninger Formularium (2006). Groninger Formularium, 5th edn. Groningen, the Netherlands

Borgnolo G, Simon G, Francescutti C, Lattuada L, Zanier L (2001) Antibiotic prescription in Italian children: a population-based study in Friuli Venezia Giulia, north-east Italy. Acta Paediatr 90(11):1316–1320

Ekins Daukes S, McLay JS, Taylor MW, Simpson CR, Helms PJ (2003) Antibiotic prescribing for children. Too much and too little? Retrospective observational study in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56(1):92–95

Schindler C, Krappweis J, Morgenstern I, Kirch W (2003) Prescriptions of systemic antibiotics for children in Germany aged between 0 and 6 years. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 12(2):113–120

Thrane N, Steffensen FH, Mortensen JT, Schonheyder HC, Sorensen HT (1999) A population-based study of antibiotic prescriptions for Danish children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 18(4):333–337

van den Bosch W, Bakx C, van Boven K (2007) Impetigo: dramatische toename van voorkomen en ernst. Huisarts Wetenschap 50(4):147–149

Kuyvenhoven MM, van Balen FA, Verheij TJ (2003) Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions from 1992 to 2001 in the Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother 52(4):675–678

http://www.farmanco.knmp.nl. Accessed 26 September 2007

van der Linden MW, van Suijlekom, Smit LW, Schellevis FG, van der Wouden JC (2005) Tweede nationale studie naar ziekten en verrichting in de huisartsenpraktijk; het kind in de huisartsenpraktijk. Erasmus MC Afdeling huisartsgeneeskunde, Rotterdam

Bauchner H, Pelton SI, Klein JO (1999) Parents, physicians, and antibiotic use. Pediatrics 103(2):395–401

Larrabee T (2002) Prescribing practices that promote antibiotic resistance: strategies for change. J Pediatr Nurs 17(2):126–132

Mangione Smith R, Elliott MN, Stivers T, McDonald LL, Heritage J (2006) Ruling out the need for antibiotics: are we sending the right message? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160(9):945–952

Little P (2005) Delayed prescribing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infection. Br Med J 331(7512):301–302

Marchetti F, Ronfani L, Conti Nibali S, Bonati M, Tamburlini G (2004) Restricted indications for the use of antibiotics in acute otitis media. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60(4):293–294

Sharland M, Kendall H, Yeates D, Randall A, Hughes G, Glasziou P et al. (2005) Antibiotic prescribing in general practice and hospital admissions for peritonsillar abscess, mastoiditis, and rheumatic fever in children: time trend analysis. Br Med J 331(7512):328–329

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Jong, J., van den Berg, P.B., de Vries, T.W. et al. Antibiotic drug use of children in the Netherlands from 1999 till 2005. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 64, 913–919 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0479-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0479-5