Abstract

Understanding spatial heterogeneity in reproductive success among at-risk populations facing localised threats is key for conservation. Sea turtle populations often concentrate at one nesting site, diverting conservation efforts from adjacent smaller rookeries. Poilão Island, Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau, is a notable rookery for green turtles Chelonia mydas within the João Vieira-Poilão Marine National Park, surrounded by three islands (Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira), with lower nesting activity. Poilão’s nesting suitability may decrease due to turtle population growth and sea level rise, exacerbating already high nest density. As the potential usage of secondary sites may arise, we assessed green turtle clutch survival and related threats in Poilão and its neighbouring islands. High nest density on Poilão leads to high clutch destruction by later turtles, resulting in surplus eggs on the beach surface and consequently low clutch predation (4.0%, n = 69, 2000). Here, the overall mean hatching success estimated was 67.9 ± 36.7% (n = 631, 2015–2022), contrasting with a significantly lower value on Meio in 2019 (11.9 ± 23.6%, n = 21), where clutch predation was high (83.7%, n = 98). Moderate to high clutch predation was also observed on Cavalos (36.0%, n = 64) and João Vieira (76.0%, n = 175). Cavalos and Meio likely face higher clutch flooding compared to Poilão. These findings, alongside observations of turtle exchanges between islands, may suggest a source-sink dynamic, where low reproductive output sink habitats (neighbouring islands) are utilized by migrants from Poilão (source), which currently offers the best conditions for clutch survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Understanding the spatial heterogeneity of reproductive success among populations of conservation concern is critical to develop and implement effective measures for their safeguarding and guide the allocation of conservation efforts (Hays et al. 2019; Welbergen et al. 2020; Assersohn et al. 2021). This is particularly important for populations facing localised threats (Allen and Singh 2016), as dispersing breeding efforts may counteract the effect of restricted reproductive failures (e.g., Bowen et al. 1989; Refsnider and Janzen 2010). Occasionally, locally threatened populations may exhibit source-sink dynamics, where sink habitats (those where reproductive success is low) are persistently used, sustained by nearby abundant sources of reproductive individuals (Pulliam 1988; Pulliam and Danielson 1991). The potential for these sink habitats to confer protection can change in the medium and long term, particularly under global environmental changes.

Sea turtles, a group of conservation concern (Godley et al. 2020) that depends on sandy beaches for egg incubation, often aggregate at one geographically restricted nesting site, with this site being the target of long-term conservation efforts. This can result from the geographic isolation of nesting sites, as in the case of the green turtle Chelonia mydas rookeries at Ascension (Mortimer and Carr 1987) and Raine Islands (Hamann et al. 2022). But even when other seemingly suitable nearby nesting habitats exist, populations may largely concentrate at specific sites (for instance, approximately 75% of the loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta nesting in the entire Cabo Verde archipelago concentrate in Boa Vista Island (Marco et al. 2012, 2015)). The underlying causes for this can be varied and multifactorial, and may be linked to historical preservation of turtle nesting sites associated with cultural traditions (Liu 2017), limited human access or low human population density (Catry et al. 2002), distinct local environmental conditions and philopatric behaviour (Stiebens et al. 2013).

Since sea turtles offer no parental care, nest-site selection is fundamental for offspring survival (Patrício et al. 2018). During incubation, the developing embryos can be exposed to harmful environmental conditions, such as extreme high sand temperatures or flooding (Fuentes and Cinner 2010; Pike 2014; Booth 2017; Montero et al. 2018; Limpus et al. 2020; Maurer et al. 2021). On several beaches, predation is also a major source of embryo and hatchling mortality (Butler et al. 2020). Predator species vary geographically, and may include mammals, birds, reptiles and crabs (Stokes et al. 2024). Several studies suggest that nesting turtles may rely on environmental cues to choose nesting sites (Wilson 1998; Wood and Bjorndal 2000), and may even select beaches with reduced predatory activity (Martins et al. 2022a), enhancing clutch survival.

Sea turtles are however generally limited in their nest-site choice, as they display natal homing, returning to the geographic area where they hatched to reproduce (Brothers and Lohmann 2015; Lohmann and Lohmann 2019; Levasseur et al. 2019). Additionally, some species exhibit high nest-site fidelity, laying consecutive clutches on the same beach (Kamel and Mrosovsky 2004; Heredero Saura et al. 2022), within the same location of the beach (Kamel and Mrosovsky 2005, 2006; Patrício et al. 2018; Shimada et al. 2021), even across nesting seasons (Heredero Saura et al. 2022). However, limited nest-site plasticity has also been reported for different sea turtle populations (e.g., Hart et al. 2013; Esteban et al. 2015, 2017; Iverson et al. 2016; Hamilton et al. 2021). This plasticity can strengthen overall reproductive success (Schofield et al. 2010; Hart et al. 2019; Hamilton et al. 2021) and increase the ability to cope with the loss or degradation of nesting areas (Esteban et al. 2017), for example through the colonisation of new areas (Luna-Ortiz et al. 2024).

The Bijagós Archipelago, in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, gathers one of the largest breeding aggregations of green turtles globally (Patrício et al. 2019) and thus is a key area for the conservation of this species. Nesting occurs on several islands of the Bijagós, but the vast majority of clutches are laid on Poilão, a small island located in the southeast of the archipelago, within a marine protected area (MPA), the João Vieira-Poilão Marine National Park (hereafter ‘JVPMNP’; (Catry et al. 2009)). The mean number of clutches per year at Poilão was estimated at circa 25,000 from 2017 to 2021 (Catry et al. 2023), and the number of nests per year has been increasing in the last twenty years (Broderick and Patrício 2019; Patrício et al. 2019; IBAP, unpublished data). Besides Poilão, this MPA encompasses three other islands where sea turtles also nest (Catry et al. 2002, 2009). However, the nesting population is highly concentrated on Poilão. This island is expected to face increased vulnerability to climate change related threats in the near future, including rising incubation temperatures and expanding flooded areas due to sea level rise (SLR; (Patrício et al. 2019)). Furthermore, the high nest density at Poilão can potentially result in density-dependent nest destruction by later nesting turtles (Booth et al. 2020) and enhance the spread of pathogens, reducing clutch survival (Bézy et al. 2015).

As Poilão may become less suitable for nesting due to population growth and climate change, it is important to explore the potential of neighbouring islands as alternative rookeries. Here, we aim to assess clutch survival and associated threats at Poilão and at the three nearby islands within the JVPMNP. To do this, we (1) estimate the total number of nests and (2) quantify clutch predation and nest flooding events within the JVPMNP. Additionally, we estimate the hatching success at Poilão and one of its neighbouring islands for which data is available.

Materials and methods

Study site

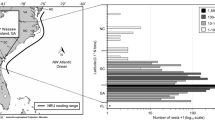

The João Vieira-Poilão Marine National Park (JVPMNP) is located on the southeast of the Bijagós Archipelago, in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa (N11°17’, W15°58’, Fig. 1A). The park encompasses a total area of 49,500 ha, of which approximately 1,485 ha corresponds to the four main islands (Poilão, Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira), all fringed by low-lying sandy beaches. The 43 ha island of Poilão (10°52’N, 15°43’W, Fig. 1B) is the smallest and hosts the largest green turtle rookery in the archipelago (Catry et al. 2002, 2009) and the second largest in the Atlantic (Broderick and Patrício 2019). João Vieira (11°02’N, 15°38’W, Fig. 1B), Meio (10°58’N, 15°40’W, Fig. 1B) and Cavalos (11°00’N, 15°42’W, Fig. 1B) have areas of 900, 402 and 210 ha, respectively. The main green turtle breeding season at the JVPMNP extends from mid-June to mid-December, with a peak nesting activity in August and September (Catry et al. 2002).

Poilão is considered a sacred site to local communities and human presence is forbidden except for rare traditional events and sea turtle monitoring activities, which enhances effective turtle protection (Catry et al. 2009; Barbosa et al. 2018a). Of the three remaining islands, João Vieira is the only one with permanent human occupation, consisting of very few people running a seasonal touristic facility. However, João Vieira and Meio annually host seasonal fishing camps and, from time to time, farmers and their families settle on these islands to engage in slash-and-burn rice agriculture, locally known as “m’pam-pam” (Barbosa et al. 2018a; Catry et al. 2018). These families, primarily from Canhabaque Island but also from other islands within the archipelago, reside there for several months until the harvesting period. Historical records indicate that the slash-and-burn rice agriculture was performed in João Vieira in 2002, 2006 and 2017, and in Meio in 1986, 2009, 2012 and 2014 (Catry et al. 2018). The practice of slash-and-burn rice agriculture near the beach can reduce the availability of shaded, cooler nesting sites for sea turtles (Patrício et al. 2017), thus decreasing male hatchling production and potentially decreasing the availability of sites with optimal thermal conditions for egg incubation under future global warming (Patrício et al. 2017). Additionally, this agricultural practice is associated with the consumption of turtle meat (Barbosa et al. 2018b). In the last harvesting period at Meio in 2014, a minimum of 87 adult female turtles were reported to be poached, although the actual number of turtles killed and consumed may have been significantly higher (Barbosa et al. 2018b). Similarly, the camping of seasonal fishers may contribute to the use of females as a food source, thereby increasing mortality rates. Cavalos is not sought for these practices and human influence resumes to the presence of feral pigs, a known sea turtle nest predator (Cruz et al. 2005; Hitipeuw et al. 2007; Whytlaw et al. 2013; Zárate et al. 2013).

Relative nesting abundance per island

Green turtle nesting activity has been continuously monitored at Poilão throughout most of the breeding season (from August to November) since the year 2000, by the Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas (in english Institute of Biodiversity and Protected Areas, IBAP) of Guinea-Bissau (Barbosa et al. 2018b), and since 2007 monitoring protocols were standardized. Each night, the IBAP patrols the beach around the peak of the high tide (see Patrício et al. 2018) to count all females encountered on the beach, and each morning (between 06:00 and 08:00) the number of turtle tracks from the previous night are recorded. Monitoring of nesting activities (daily and nightly surveys) at Meio started in 2019, but only from August to October. This shorter monitoring period precludes systematic nest exhumation since a large proportion of clutches have yet to hatch by the end of the monitoring campaign. At João Vieira, the monitoring began in 2020, with daytime beach surveys conducted twice a week, usually between August and October. No regular monitoring is conducted at Cavalos. The differences in monitoring levels across the four islands of the park result from the difficulty and high costs to access these remote sites. For this study, we used the green turtle nesting database from Poilão, along with all available nesting data from Meio (2019, 2020 and 2021), João Vieira (2011, 2020 and 2021) and Cavalos (2016).

To estimate the total number of nests laid by breeding turtles at Poilão, we relied on the counts of turtle tracks. This approach is necessary due to the high nest density at Poilão, which makes it impractical to accurately count all nests, as the activity of new turtles obscures the tracks left by earlier ones. Consequently, we first used linear interpolation, based on the number of tracks noted in the previous and following days, to estimate the number of tracks on rare occasions when weather conditions precluded beach surveys (Godley et al. 2001). Then, we divided the resulting total number of tracks by two (ascending and descending tracks) to obtain the number of nesting female emergences, and multiplied this figure by 0.813, to adjust for nesting success in Poilão estimated by Catry et al. (2009) (81.3%, n = 75 monitored adult female emergences). The temporal distribution of nesting is well known at Poilão from earlier census, and thus, to account for a short period at the onset and at the end of the breeding season when no track counts were performed, we multiplied the previous estimate (i.e., tracks/2 × 0.813) by a factor of 1.05, following Catry et al. (2009).

For the other islands, the actual number of nests were counted during surveys. We assumed that the green turtle temporal nesting distribution was consistent across islands. This decision was based on local observations confirming synchronous nesting patterns across the JVPMNP. Hence, we used the known temporal distribution of green turtle nesting at Poilão as a model to extrapolate the number of nests observed during surveys at Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira to the entire breeding season.

Turtle nest densities per island

We estimated the available nesting areas at Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira by using Google Satellite Imagery in QGIS version 3.26 software. On the high-resolution images of the islands, we delimited the available nesting area per island using the QGIS Create Layer tool, and then calculated the area of the polygons using the $area function. We considered ‘available nesting area’ as the sandy areas above the high tide line. This is a very broad approximation since some areas may be perceived as suitable in the satellite images but be regularly flooded, while some areas under the forest border canopy were not detectable using satellite imaging. For Poilão, we used the estimation of the available nesting area previously published (Patrício et al. 2018), which was based on on-site measurements. The spatial density of green turtle nests was calculated by dividing the number of estimated nests by the estimated available nesting area, for each survey year.

Hatching success at Poilão and Meio

To assess green turtle hatching success at Poilão, up to four nests per night were uniquely numbered and marked with wooden sticks, between August and October, from 2013 to 2022, and surveyed daily until nest excavation (1–5 days after hatchling emergence). Because in 2013 and 2014 the clutches were given extra protection using larger, reinforced wooden sticks, which may have prevented disturbances such as destruction by other turtles, we discarded these two years from the hatching success estimations. Upon nest exhumations, after hatchling emergence, we recorded the number of hatched and unhatched eggs, and of live and dead hatchlings found inside the nest chamber. Then, we estimated clutch size (the sum of hatched and unhatched eggs) and hatching success (number of hatched eggshells / clutch size). On occasions, the whole clutch was washed by spring tides, and we considered hatching success to be zero. Additionally, some nests were ‘lost’ due to the displacement or covering with sand of wooden sticks by turtles. It is important to note that the term ‘lost’ does not necessarily imply complete loss or a hatching success rate of zero. Some of the ‘lost clutches’ were likely partially or totally destroyed by the action of nesting turtles while digging the body pit, the egg chamber or while covering their nest. However, many others probably remained intact, raising the possibility that ‘lost clutches’ may have had higher hatching success rates (> 0%). The fate of these ‘lost clutches’ remains uncertain, and as we cannot determine the extent of potential success (ranging from 0 to 100%), we initially discarded them from the estimation of hatching success. Acknowledging the potential for overestimation of hatching success resulting from this approach, we also calculated the mean annual hatching success rates attributing a hatching success value of zero to all ‘lost clutches’.

We used a Kruskal-Wallis test to compare hatching success across years. We then calculated the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to test the association between the mean hatching success and the number of estimated nests per breeding season. In 2019, hatching success was estimated at Meio for a subset of 21 clutches laid between August 3 and August 28, which were monitored until hatching. The hatching success formula used for Meio was the same as that used in Poilão. Hatching success was not estimated at Cavalos or João Vieira for any of the study years due to the absence of teams in the field during the hatching season.

Clutch predation and flooding

Clutch predation at Poilão was previously published in Catry et al. (2002). An accurate monitoring of the number of nests that were at least once covered by the tide or flooded by rainfall exists only for the years 2013 and 2014.

In the remaining islands, dedicated surveys were conducted to estimate the levels of clutch predation and flooding, specifically in 2011 at João Vieira (only clutch predation was recorded), in 2016 at Cavalos, and in 2019 at Meio. During these surveys, nests were marked with wooden sticks and monitored during the first 10 days after oviposition, since this is the period of peak predatory activity (Leighton et al. 2011; Barbosa et al. 2018b). Clutch predation by Nile monitors Varanus niloticus and ghost crabs Ocypode cursor (the most common egg predators in the park; (Barbosa et al. 2018b)) was identified by the presence of fresh eggshells scattered around the nests, along with these species’ distinctive tracks. Confirmation was obtained in a number of nests located in João Vieira Island by the use of time-lapse cameras. We defined the occurrence of a flooding event as the submersion of a nest in water, resulting from high tide or rainfall.

Results

Relative nesting abundance and density per island

There was a high inter-annual variation in the abundance of green turtle nests in Poilão from 2007 to 2022. The number of estimated nests per breeding season fluctuated between a minimum of 4,176 in 2012 and a maximum of 71,032 in the peak year of 2020, with an average (± SD) of 32,608 ± 33,327 nests per year in the interval 2020–2022 (n = 97,824 estimated nests between 2020 and 2022). Poilão hosts approximately 90% of the nests within the JVPMNP (Table 1).

The number of estimated nests per year on the islands of Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira ranged from 38 to 2,461 (Table 1). These correspond to 0.2% (on João Vieira in 2021) to 7.7% (on Cavalos in 2016) of the nests at Poilão in the same years (Table 1). Cavalos is the island hosting more nests after Poilão, followed by Meio and then João Vieira. On the two islands for which there are estimates of the number of nests for the two most recent years (Meio and João Vieira), these follow the inter-annual variation of the nesting abundance in Poilão (Table 1). However, the percentage of nests in João Vieira in relation to Poilão decreased from the earlier survey in 2011 in comparison to the two most recent surveys (Table 1). Across all survey years, nest densities at Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira were much lower than those estimated for Poilão, ranging from 0.002 to 0.206 nests m− 2 (Table 1). In comparison, for the same survey years, nest densities at Poilão were consistently one order of magnitude higher, varying between 0.44 and 2.04 nests m− 2 (Table 1).

Hatching success at Poilão and Meio

The estimated mean (± SD) hatching success for green turtles at Poilão between 2015 and 2022 was 67.9 ± 36.7% (n = 631 monitored nests until hatching, ranging between 42.5 ± 39.1% in 2020, n = 72 monitored nests, and 84.4 ± 22.9% in 2016, n = 55 monitored nests). Hatching success at Meio in 2019 was low: 11.9 ± 23.6% (mean ± SD, n = 21 monitored nests until hatching). Unsuccessful nests had signs of predation by Nile monitors and ghost crabs.

At Poilão, hatching success varied significantly across years (Kruskal-Wallis test, H7 = 93.367, P < 0.001, Fig. 2). There was no relation between the mean hatching success and the number of estimated nests per breeding season (Spearman rank correlation, rs = -0.40, n = 8, P = 0.32, Fig. S1). Between 2015 and 2022, the location of 222 out of the 853 (26.0%) monitored nests was lost. Given the possibility of an overestimation of the hatching success (by excluding lost clutches from the analysis), we recalculated this parameter attributing a hatching success value of zero to all monitored nests for which we lost their location. We emphasize that this approach underestimates the actual hatching success by assuming that all ‘lost clutches’ had 100% mortality. Under this assumption, overall mean (± SD) hatching success was 49.7 ± 43.5% (n = 853 monitored nests, Fig. S2), and varied across years (Fig. S2), with significant lower mean (± SD) hatching success in 2020 (26.4 ± 37.1%, n = 116 monitored nests, Fig. S2), but still much higher than the single estimate for Meio.

Clutch predation and flooding

Predation was highly variable across the JVPMNP, being very low at Poilão and moderate to very high at the remaining islands (Table 2). The Nile monitor was the main nest predator on all islands (Table 2). Out of the 175 monitored nests for predation at João Vieira, 22 (12.6%) were simultaneously observed using time-lapse cameras. The video footage confirmed that Nile monitors were the exclusive species preying on green turtle nests here, accounting for 100% of the observed instances (n = 74).

Flooding incidence differed among islands, affecting less than 25% of the nests at Poilão, to over 40% at Cavalos (Table 2). At Poilão, where nest exhumations were conducted, we were able to determine the hatching success of flooded clutches. Here we used the data from 2013 to 2014, when large, reinforced wooden sticks were used to prevent clutch destruction by other turtles (as mentioned above), to specifically evaluate the impact of flooding.

In 2013, the mean (± SD) hatching success for flooded nests at Poilão was 48.4 ± 41.2% (n = 58 monitored nests), with 38.5% of these clutches having 0.0 to 4.2% hatching, and the remaining with values between 50.0 and 97.9%. In 2014, mean (± SD) hatching success of flooded nests at Poilão was 35.7 ± 26.4% (n = 66 monitored nests). Among these, one clutch was entirely unsuccessful, whereas the remaining 98.5% had hatching rates varying from 25.0 to 91.5%. We have no data on nest flooding for the island of João Vieira.

Discussion

Our study compiles information from four islands within the João Vieira-Poilão Marine National Park (JVPMNP) in Guinea-Bissau, including the important green turtle rookery at Poilão, to assess reproductive output parameters and evaluate habitat suitability across these diverse sites. We show that the prevalence of clutch predation and/or flooding was higher on the satellite rookeries. Lower survival at satellite colonies and the maintenance of linkages between islands may suggest the existence of a source-sink dynamic.

Hatching success

The mean hatching success found in this study (67.9 ± 36.7%, excluding all lost clutches from the calculation), is close to what was previously reported (2013–2014: 65.4 ± 33.9%; (Patrício et al. 2017)), and within the range of values described for other green turtle rookeries, e.g., on Ascension Island (57.0–85.0%; (Broderick et al. 2001)) and on Akyatan Beach, Turkey (58.0–67.0%; (Turkozan et al. 2011)). Nevertheless, both higher (91.6%, Akumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico; (Santos et al. 2017)) and lower (42.0–57.0%, Tortuguero, Costa Rica; (Fowler 1979), 46.0%, Galápagos Islands; (Zárate et al. 2013)) values of mean hatching success have also been reported. Assuming 100% mortality for all nests with lost locations probably resulted in an underestimate of the hatching success, given that lost nests likely include a mix of disturbed and undisturbed clutches. Nonetheless, this exercise shows that even under the most conservative estimate, Poilão nesting grounds still guarantee mean to high hatching success on several years (3 out of 8 years with hatching success above 50%, Fig. S2). It is important to emphasize that our estimation of clutch size involved counting both hatched and unhatched eggs during nest exhumations. Previous research has shown that at sites where nest predation by crabs is prevalent, there may be a tendency for clutch size to be underestimated (Stokes et al. 2024). However, in the case of Poilão, while we acknowledge the occurrence of nest predation, it typically occurs at low intensity (Catry et al. 2002). Therefore, given the limited impact of nest predation in Poilão, the likelihood of bias in our clutch size estimates is low.

Generally, a higher number of nests on Poilão did not correspond to a decrease of average hatching success rates. This suggests that, on most years, turtles are not yet overcrowding the available nesting space. In 2020, however, the low hatching success observed may have been a density-dependent phenomenon, wherein an exceptionally large number of nesting turtles resulted in increased clutch disturbance. In this peak nesting year, under the assumption of uniform nest distribution throughout the beach, our estimations suggest a density of over 2 nests per square meter at Poilão. We know however that some sections of the beach are more heavily used (Patrício et al. 2018), and in these preferred areas the nest density can be considerably higher, potentially reaching a level that affects clutch survival, for example, through increased clutch disturbance or reduced available oxygen.

Clutch survival and mortality factors

Whilst Poilão exhibits a high concentration of green turtle nests, nest predation is very low. This may result from a density-dependent predator satiation effect (Eckrich and Owens 1995). At Poilão, nesting turtles destroy a high number of clutches (Catry et al. 2009), therefore, there is a considerable amount of aboveground scattered eggs available to consumers, and predators do not need to excavate nests actively searching for this food source. Despite nest destruction also contributing to mortality, hatching success at Poilão consistently maintained mean to high levels over several years, even with the assumption that all lost clutches were entirely destroyed. In contrast, predation significantly reduces hatching success on Meio, the other island for which we were able to estimate hatching success. However, it should be noted that the low sample size used for hatching success estimation and the lack of inter-annual data available for Meio are two limitations of this study. Overall, predation on other islands of the JVPMNP impacted a moderate to very high proportion of green turtle clutches. Several studies have reported similar values of nest predation to those found in our study (e.g. 27.7%; (Engeman et al. 2003), 44.9%; (Butler et al. 2020), 53.3%; (Engeman et al. 2005), 89.6%; (Whytlaw et al. 2013)). Within the Bijagós Archipelago, sea turtle nest predation was also reported to be high at smaller rookeries in the Orango National Park, with estimates around 50% (Barbosa et al. 1998), and on the island of Canhabaque, where it reached 97% (Camará 2023). Nile monitors were the main predator of green turtle eggs, similarly to what was previously described for the JVPMNP (Catry et al. 2002; Barbosa et al. 2018b). These are generalist predators, with the ability to detect prey odours, that can adapt their foraging behaviour according to available food sources (Losos and Greene 1988). Ghost crabs are important turtle egg predators globally (Witherington 1999; Barton and Roth 2008; Marco et al. 2015; Martins et al. 2022a), yet at the JVPMNP they probably act as local opportunistic predators, considering the seldom observed predatory activity. One limitation of this study is that clutches on Poilão’s neighbouring islands were primarily monitored during the initial 10 days after oviposition, covering only a portion of the incubation phase. Despite this limited observation period, predation levels on these islands were significantly higher than those on Poilão. If the uneven sampling had introduced any bias, it would likely have skewed the results in the opposite direction of the observed differences. On top of clutch predation, the predation of hatchlings can contribute to very low reproductive success on the islands of Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira.

Nest flooding varied across the JVPMNP, with Poilão experiencing 24.0% in 2013 and 12.0% in 2014. On the islands of Cavalos and Meio the rates were higher, 42.0% and 36.7%, respectively. Flooding at JVPMNP main islands occurs because of the low-lying setting of these nesting sites. This geographical characteristic can potentially enhance vulnerability to increases in sea level (Baker et al. 2006; Lyons et al. 2020) and coastal erosion (Siqueira et al. 2021) across all islands. Interestingly, not every nest affected by tidal washing experienced reduced hatching success. This appears to be linked to both the duration of the flooding event and the stage of development of the embryos. Limpus et al. (2020) observed that clutches either freshly laid or close to hatching suffered complete mortality in brief flooding events, a fate shared by all eggs subjected to extended periods of flooding (lasting 24 and 48 h). However, eggs in the mid-development phase (20–80%) exposed to short-term flooding (1–6 h) showed a notably high hatching success rate (Limpus et al. 2020). Recent studies have proposed that temporary flooding might help lower incubation temperatures, potentially increasing the production of male hatchlings (Laloë et al. 2016; Martins et al. 2022b). Future nest excavation studies will be vital to further understanding the effects of flooding on green turtle nests at the JVPMNP. Nevertheless, we showed a very significant prevalence of flooding on the adjacent islands of Poilão, which is expected to increase under climate change scenarios (Horton et al. 2014; Dutton et al. 2015), emphasizing the constrained potential of these sites to support sea turtle reproduction in the future.

Although systematic surveys are not regularly conducted on Poilão’s neighbouring islands due to logistical constraints, non-systematic field observations indicate that the results reported by our work are representative of other years. Our study revealed that clutch predation in Meio and João Viera was approximately twenty times higher than that at Poilão during the study years. Similarly, clutch flooding at Cavalos and Meio was about two to three times higher than that at Poilão during those years. The JVPMNP covers a relatively small area, making it highly probable that a specific annual event occurs on all the islands within its boundaries. Given that clutch predation and flooding on the other JVPMNP islands consistently exceeded those at Poilão, it is unlikely that we randomly selected poor years to survey the other islands.

Suitable nesting sites

Poilão is the island that currently gathers the best conditions for green turtle clutch survival within the JVPMNP. Nevertheless, this may change in the future due to population growth, to climate change related threats, namely global mean SLR, or to a combination of both. If the nesting female population continues to increase, Poilão may start to experience moderate to high levels of nest destruction. Indeed, substantial nest destruction by subsequent nesting turtles has been found among green turtle (11%; (Tiwari et al. 2006)) and olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea (18%; (Ocana et al. 2012)) populations. In addition, SLR will further decrease the available nesting area at Poilão (predictions of 33.4 to 43.0% of beach loss by the year 2100 using a bath-tub model; (Patrício et al. 2019)), which will result in increased nest density and therefore an intensification of density-dependent nest destruction (Bustard and Tognetti 1969; Girondot et al. 2002; Tiwari et al. 2006, 2010). Additionally, the packing of nests may enhance microbial infection in incubating eggs (Bézy et al. 2015; Assersohn et al. 2021), lowering clutch survival through embryo mortality. Collectively, these factors may lead to reduced hatching success at Poilão over the coming years.

If the nesting conditions at Poilão deteriorate, leading to increased clutch destruction, it is important for turtles to begin laying at the best alternative nesting sites available.

Cavalos seems to be that best alternative nesting site within the JVPMNP, primarily owing to its relatively low predation levels. However, it is important to note that Cavalos experiences considerable flooding. This is further compounded by its low-lying geography and the presence of an interior lagoon that connects to the sea during high tides, resulting in increased water content. The islands of Meio and João Vieira are currently heavily impacted by predation, but they have a higher profile and thus may be less vulnerable to SLR impacts. Nevertheless, coastal squeeze (i.e., beach narrowing (Silva et al. 2020)) derived from erosion and rising sea levels, is expected to reduce the current available nesting area on all islands (Fish et al. 2005; Fuentes et al. 2010) and cause higher clutch mortality due to seawater inundation (Varela et al. 2019).

Management priorities and recommendations

Given the proportion of predated clutches reported in this study, the adoption of predation mitigation measures on the satellite colonies focused on the Nile monitor population should be considered, for example the use of protective mesh nets against terrestrial predators (O’Connor et al. 2017; Lovemore et al. 2020). Additionally, a study in Cavalos tested the use of a strong scent to disguise the natural odour of clutches, with some degree of success (Sampaio et al. 2022). The relocation of turtle eggs that are vulnerable to flooding to safer areas in the same beach has also been largely used to enhance clutch survival (e.g., Margaritoulis 1988; Ilgaz and Baran 2001; Chacón-Chaverri and Eckert 2007; Martins et al. 2022b). However, if clutch relocation was implemented, it would be important to leave some clutches in-situ to record hatching success and assess the impact of flooding.

As for other threats, although Cavalos does not have the same extent of traditional taboos as Poilão, it is also a sacred island where several activities are forbidden (agriculture, tree cutting, establishing fishing camps) and it is well protected (Catry et al. 2009). At present, it seems that the feral pigs do not pose a threat to green turtle clutches at Cavalos (Catry et al. 2018). Yet, if the green turtle population of the JVPMNP continues to grow, clutch predation by feral pigs would have to be re-evaluated (Whytlaw et al. 2013; Engeman et al. 2016; Nordberg et al. 2019). Enhanced protection of nesting turtles associated with heightened awareness specifically focused on turtle conservation could prove beneficial for Meio and João Vieira (e.g., Airaud et al. 2020). This becomes particularly crucial as turtle population growth continues and given the high risk of poaching during the slash-and-burn rice agriculture by the Bijagós people.

The limited occurrence of linkages between different islands of the JVPMNP from 2018 to 2020 was previously reported (Raposo et al. 2023). Furthermore, recent information from female green turtles flipper-tagged at Poilão and Meio in 2021 and 2022 has shown that exchanges between rookeries are maintained. In 2021, 1 out of 62 flipper-tagged turtles at Meio was re-sighted at Poilão (IBAP, unpublished data). It is noteworthy that these numbers reflect a limited survey effort per island for tagging and recapturing turtles, and thus the level of exchange between islands could be much higher than that detected. This inter-island exchange, coupled with the high clutch predation and/or flooding observed at Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira point to the existence of a source-sink dynamic (Pulliam 1988; Dias 1996), with Poilão acting as the source habitat and the remaining islands as sink habitats. It is well established that local threatened subpopulations can exhibit source-sink dynamics, where low-quality habitats (sinks) persist because they are sustained by the surplus individuals originated in high-quality habitats (sources; (Pulliam 1988)). This has been documented among loggerhead turtles in Cabo Verde (Baltazar-Soares et al. 2020) and leatherback turtles Dermochelys coriacea on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica (Santidrián-Tomillo et al. 2017). If confirmed, this dynamic would have significant demographic implications for the population nesting at the JVPMNP. Given the observed low reproductive success on alternative islands, there is a concern that Cavalos, Meio and João Vieira may not be able to serve as a potential replacement for Poilão if this site becomes unsuitable for nesting. We suggest that future studies assess the existence of a source-sink dynamic, to better inform conservation strategies and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the green turtle population in the JVPMNP.

Currently, monitoring efforts across JVPMNP islands are dictated by the significance of Poilão as a globally and locally important green turtle rookery. Cavalos is not monitored and there is a considerable gap in understanding sea turtle population ecology on this island. Hence, we propose that studies addressing green turtle reproductive success and associated threats are needed. In addition, research endeavours should focus on the role of density-dependent processes on the green turtle population at Poilão (e.g., Caut et al. 2005; Tiwari et al. 2006). Nevertheless, the costs and benefits linked to targeted conservation efforts in the JVPMNP must be considered. Decision-makers should consider the findings of this study, which identify Poilão as a probable source habitat that likely supports the other satellite colonies of the park, which are probable sink habitats.

The Bijagós Archipelago comprises 88 islands and islets (Catry et al. 2009) and prior research revealed that green turtles nest or nested in virtually all of its islands (Barbosa et al. 1998; Catry et al. 2009; Camará 2023). For instance, nesting beyond the JVPMNP boundaries has been documented in the Orango National Park, with an estimate of 200–300 nests per year (Barbosa et al. 1998), and on Canhabaque Island, where 33 nests were recorded between August 20 to September 16, 2023 (Camará 2023). Potentially, other islands of the Bijagós Archipelago can provide more favourable nesting conditions in the future, thus, conducting a comprehensive analysis of the green turtle reproductive success within the Bijagós Archipelago would be most beneficial.

Data availability

All data analysed during this study will be provided upon reasonable request submitted to the corresponding author.

References

Airaud BF, Vieira S, Barbosa C, Posto-Merba I, Nuno A (2020) Comportamentos E percepções das comunidades locais da Guiné-Bissau sobre as tartarugas marinhas e o seu contexto social. económico e cultural

Allen AM, Singh NJ (2016) Linking movement ecology with wildlife management and conservation. Front Ecol Evol 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00155

Assersohn K, Marshall AF, Morland F, Brekke P, Hemmings N (2021) Why do eggs fail? Causes of hatching failure in threatened populations and consequences for conservation. Anim Conserv 24:540–551. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12674

Baker J, Littnan C, Johnston D (2006) Potential effects of sea level rise on the terrestrial habitats of endangered and endemic megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Endanger Species Res 2:21–30. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr002021

Baltazar-Soares M, Klein JD, Correia SM, Reischig T, Taxonera A, Roque SM, Dos Passos L, Durão J, Lomba JP, Dinis H, Cameron SJK, Stiebens VA, Eizaguirre C (2020) Distribution of genetic diversity reveals colonization patterns and philopatry of the loggerhead sea turtles across geographic scales. Sci Rep 10:18001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74141-6

Barbosa C, Broderick A, Catry P (1998) Marine turtles in the Orango National Park (Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau). Mar Turt Newsl 6–7

Barbosa C, Pires A, Regalla A, Catry P (2018a) Comunidades Humanas E utilização Dos Recursos Naturais. In: Catry P, Regalla A (eds) Parque Nacional Marinho João Vieira E Poilão: Biodiversidade E Conservação. IBAP - Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas, Bissau, pp 329–357

Barbosa C, Patrício R, Ferreira B, Sampaio M, Catry P (2018b) Tartarugas Marinhas. In: Catry P, Regalla A (eds) Parque Nacional Marinho João Vieira E Poilão: Biodiversidade E Conservação. IBAP - Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas, Bissau, pp 117–140

Barton BT, Roth JD (2008) Implications of intraguild predation for sea turtle nest protection. Biol Conserv 141:2139–2145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.06.013

Bézy VS, Valverde RA, Plante CJ (2015) Olive Ridley sea turtle hatching success as a function of the microbial abundance and the microenviroment of in situ nest sand at Ostional, Costa Rica. PLoS ONE 10:e0118579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118579

Booth D (2017) Influence of incubation temperature on sea turtle hatchling quality. Integr Zool 12:352–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12255

Booth DT, Archibald-Binge A, Limpus CJ (2020) The effect of respiratory gases and incubation temperature on early stage embryonic development in sea turtles. PLoS ONE 15:e0233580. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233580

Bowen BW, Meylan AB, Avise JC (1989) An odyssey of the green sea turtle: Ascension Island revisited. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. pp 573–576

Broderick A, Patrício A (2019) Chelonia mydas (South Atlantic subpopulation), Green Turtle. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T142121866A142086337.en. IUCN Red List Threat Species 2019

Broderick AC, Godley BJ, Hays GC (2001) Metabolic heating and the prediction of sex ratios for green turtles (Chelonia mydas). Physiol Biochem Zool 74:161–170. https://doi.org/10.1086/319661

Brothers JR, Lohmann KJ (2015) Evidence for geomagnetic imprinting and magnetic navigation in the natal homing of sea turtles. Curr Biol 25:392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.035

Bustard HR, Tognetti KP (1969) Green sea turtles: a discrete simulation of density-dependent population regulation. Science 163:939–941. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.163.3870.939

Butler ZP, Wenger SJ, Pfaller JB, Dodd MG, Ondich BL, Coleman S, Gaskin JL, Hickey N, Kitchens-Hayes K, Vance RK, Williams KL (2020) Predation of loggerhead sea turtle eggs across Georgia’s barrier islands. Glob Ecol Conserv 23:e01139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01139

Camará A (2023) Tamanho médio e atividade de desova das tartarugas-verdes (Chelonia mydas) no Arquipélago dos Bijagós, Guiné-Bissau. Dissertation, ISPA - Instituto Universitário

Catry P, Barbosa C, Indjai B, Almeida A, Godley BJ, Vié J-C (2002) First census of the green turtle at Poilão, Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau: the most important nesting colony on the Atlantic coast of Africa. Oryx 36:400–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605302000765

Catry P, Barbosa C, Paris B, Indjai B, Almeida A, Limoges B, Silva C, Pereira H (2009) Status, ecology, and conservation of sea turtles in Guinea-Bissau. Chelonian Conserv Biol 8:150–160. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-0772.1

Catry P, Pires AJ, Barbosa C, Cordeiro JS, Tchantchanlam Q, Regalla A (2018) Ameaças E conservação. In: Catry P, Regalla A (eds) Parque Nacional Marinho João Vieira E Poilão: Biodiversidade E Conservação. IBAP - Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas, Bissau, pp 359–393

Catry P, Senhoury C, Sidina E, El Bar N, Bilal AS, Ventura F, Godley BJ, Pires AJ, Regalla A, Patrício AR (2023) Satellite tracking and field assessment highlight major foraging site for green turtles in the Banc d’Arguin, Mauritania. Biol Conserv 277:109823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109823

Caut S, Hulin V, Girondot M (2005) Impact of density-dependent nest destruction on emergence success of Guianan leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Anim Conserv 9:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.163.3870.939

Chacón-Chaverri D, Eckert KL (2007) Leatherback sea turtle nesting at Gandoca Beach in Caribbean Costa Rica: management recommendations from fifteen years of conservation. Chelonian Conserv Biol 6:101–110. https://doi.org/10.2744/1071-8443(2007)6[101:LSTNAG]2.0.CO;2

Cruz F, Josh Donlan C, Campbell K, Carrion V (2005) Conservation action in the Galàpagos: feral pig (Sus scrofa) eradication from Santiago Island. Biol Conserv 121:473–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2004.05.018

Dias PC (1996) Sources and sinks in population biology. Trends Ecol Evol 11:326–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(96)10037-9

Dutton A, Carlson AE, Long AJ, Milne GA, Clark PU, DeConto R, Horton BP, Rahmstorf S, Raymo ME (2015) Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods. Science 349:6244. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4019

Eckrich CE, Owens DW (1995) Solitary versus arribada nesting in the olive Ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea): a test of the predator-satiation hypothesis. Herpetologica 51:349–354

Engeman RM, Erik Martin R, Constantin B, Noel R, Woolard J (2003) Monitoring predators to optimize their management for marine turtle nest protection. Biol Conserv 113:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00295-1

Engeman RM, Martin RE, Smith HT, Woolard J, Crady CK, Shwiff SA, Constantin B, Stahl M, Griner J (2005) Dramatic reduction in predation on marine turtle nests through improved predator monitoring and management. Oryx 39:318–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605305000876

Engeman RM, Addison D, Griffin JC (2016) Defending against disparate marine turtle nest predators: nesting success benefits from eradicating invasive feral swine and caging nests from raccoons. Oryx 50:289–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000805

Esteban N, van Dam RP, Harrison E, Herrera A, Berkel J (2015) Green and hawksbill turtles in the Lesser antilles demonstrate behavioural plasticity in inter-nesting behaviour and post-nesting migration. Mar Biol 162:1153–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-015-2656-2

Esteban N, Mortimer JA, Hays GC (2017) How numbers of nesting sea turtles can be overestimated by nearly a factor of two. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 284:20162581. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2581

Fish MR, Côte IM, Gill JA, Jones AP, Renshoff S, Watkinson AR (2005) Predicting the impact of sea-level rise on Caribbean sea turtle nesting habitat. Conserv Biol 19:482–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00146.x

Fowler LE (1979) Hatching success and nest predation in the green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, at Tortuguero, Costa Rica. Ecology 60:946–955. https://doi.org/10.2307/1936863

Fuentes MMPB, Cinner JE (2010) Using expert opinion to prioritize impacts of climate change on sea turtles’ nesting grounds. J Environ Manage 91:2511–2518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.07.013

Fuentes M, Limpus C, Hamann M, Dawson J (2010) Potential impacts of projected sea-level rise on sea turtle rookeries. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 20:132–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.1088

Girondot M, Tucker AD, Rivalan P, Godfrey MH, Chevalier J (2002) Density-dependent nest destruction and population fluctuations of Guianan leatherback turtles. Anim Conserv 5:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1367943002001099

Godley BJ, Broderick AC, Hays GC (2001) Nesting of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) at Ascension Island, South Atlantic. Biol Conserv 97:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00107-5

Godley BJ, Broderick AC, Colman LP, Formia A, Godfrey MH, Hamann M, Nuno A, Omeyer LCM, Patrício AR, Phillott AD, Rees AF, Shanker K (2020) Reflections on sea turtle conservation. Oryx 54:287–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605320000162

Hamann M, Shimada T, Duce S, Foster A, To ATY, Limpus C (2022) Patterns of nesting behaviour and nesting success for green turtles at Raine Island, Australia. Endanger Species Res 47:217–229. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01175

Hamilton RJ, Desbiens A, Pita J, Brown CJ, Vuto S, Atu W, James R, Waldie P, Limpus C (2021) Satellite tracking improves conservation outcomes for nesting hawksbill turtles in Solomon Islands. Biol Conserv 261:109240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109240

Hart KM, Zawada DG, Fujisaki I, Lidz BH (2013) Habitat use of breeding green turtles Chelonia mydas tagged in Dry Tortugas National Park: making use of local and regional MPAs. Biol Conserv 161:142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.03.019

Hart KM, Iverson AR, Benscoter AM, Fujisaki I, Cherkiss MS, Pollock C, Lundgren I, Hillis-Starr Z (2019) Satellite tracking of hawksbill turtles nesting at Buck Island Reef National Monument, US Virgin Islands: inter-nesting and foraging period movements and migrations. Biol Conserv 229:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.011

Hays GC, Bailey H, Bograd SJ, Bowen WD, Campagna C, Carmichael RH, Casale P, Chiaradia A, Costa DP, Cuevas E, Nico de Bruyn PJ, Dias MP, Duarte CM, Dunn DC, Dutton PH, Esteban N, Friedlaender A, Goetz KT, Godley BJ, Halpin PN, Hamann M, Hammerschlag N, Harcourt R, Harrison A-L, Hazen EL, Heupel MR, Hoyt E, Humphries NE, Kot CY, Lea JSE, Marsh H, Maxwell SM, McMahon CR, di Notarbartolo G, Palacios DM, Phillips RA, Righton D, Schofield G, Seminoff JA, Simpfendorfer CA, Sims DW, Takahashi A, Tetley MJ, Thums M, Trathan PN, Villegas-Amtmann S, Wells RS, Whiting SD, Wildermann NE, Sequeira AMM (2019) Translating marine animal tracking data into conservation policy and management. Trends Ecol Evol 34:459–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.01.009

Heredero Saura L, Jáñez-Escalada L, López Navas J, Cordero K, Santidrián Tomillo P (2022) Nest-site selection influences offspring sex ratio in green turtles, a species with temperature-dependent sex determination. Clim Change 170:39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03325-y

Hitipeuw C, Dutton P, Benson S, Thebu J, Bakarbessy J (2007) Population status and internesting movement of leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, nesting on the northwest coast of Papua, Indonesia. Chelonian Conserv Biol 6:28–36. https://doi.org/10.2744/1071-8443(2007)6[28:PSAIMO]2.0.CO;2

Horton BP, Rahmstorf S, Engelhart SE, Kemp AC (2014) Expert assessment of sea-level rise by AD 2100 and AD 2300. Quat Sci Rev 84:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.002

Ilgaz Ç, Baran İ (2001) Reproduction biology of the marine turtle populations in Northern Karpaz (Cyprus) and Dalyan (Turkey). Zool Middle East 24:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09397140.2001.10637884

Iverson ARS, Hart KM, Fujisaki I, Cherkiss MS, Pollock C, Lundgren I, Hillis-Starr ZM (2016) Hawksbill satellite-tracking case study: implications for remigration interval and population estimates. Mar Turt Newsl 148:2–7

Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N (2004) Nest site selection in leatherbacks, Dermochelys coriacea: individual patterns and their consequences. Anim Behav 68:357–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.021

Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N (2005) Repeatability of nesting preferences in the hawksbill sea turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, and their fitness consequences. Anim Behav 70:819–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.01.006

Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N (2006) Inter-seasonal maintenance of individual nest site preferences in hawksbill sea turtles. Ecology 87:2947–2952. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2947:IMOINS]2.0.CO;2

Laloë JO, Esteban N, Berkel J, Hays GC (2016) Sand temperatures for nesting sea turtles in the Caribbean: implications for hatchling sex ratios in the face of climate change. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 474:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2015.09.015

Leighton PA, Horrocks JA, Kramer DL (2011) Predicting nest survival in sea turtles: when and where are eggs most vulnerable to predation? Anim Conserv 14:186–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00422.x

Levasseur K, Stapleton S, Fuller M, Quattro J (2019) Exceptionally high natal homing precision in hawksbill sea turtles to insular rookeries of the Caribbean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 620:155–171. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12957

Limpus CJ, Miller JD, Pfaller JB (2020) Flooding-induced mortality of loggerhead sea turtle eggs. Wildl Res 48:142–151. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR20080

Liu TM (2017) Unexpected threat from conservation to endangered species: reflections from the front-line staff on sea turtle conservation. J Environ Plan Manag 60:2255–2271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1273824

Lohmann KJ, Lohmann CMF (2019) There and back again: natal homing by magnetic navigation in sea turtles and salmon. J Exp Biol 222:jeb184077. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.184077

Losos JB, Greene HW (1988) Ecological and evolutionary implications of diet in monitor lizards. Biol J Linn Soc 35:379–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1988.tb00477.x

Lovemore TEJ, Montero N, Ceriani SA, Fuentes MMPB (2020) Assessing the effectiveness of different sea turtle nest protection strategies against coyotes. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 533:151470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2020.151470

Luna-Ortiz A, Marín-Capuz G, Abella E, Crespo-Picazo JL, Escribano F, Félix G, Giralt S, Tomás J, Pegueroles C, Pascual M, Carreras C (2024) New colonisers drive the increase of the emerging loggerhead turtle nesting in Western Mediterranean. Sci Rep 14:1506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51664-w

Lyons MP, von Holle B, Caffrey MA, Weishampel JF (2020) Quantifying the impacts of future sea level rise on nesting sea turtles in the southeastern United States. Ecol Appl 30:e02100. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2100

Marco A, Abella E, Liria-Loza A, Martins S, López O, Jiménez-Bordón S, Medina M, Oujo C, Gaona P, Godley BJ, López-Jurado LF (2012) Abundance and exploitation of loggerhead turtles nesting in Boa Vista island, Cape Verde: the only substantial rookery in the eastern Atlantic. Anim Conserv 15:351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00547.x

Marco A, da Graça J, García-Cerdá R, Abella E, Freitas R (2015) Patterns and intensity of ghost crab predation on the nests of an important endangered loggerhead turtle population. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 468:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2015.03.010

Margaritoulis D (1988) Nesting of the loggerhead sea turtle, Caretta caretta, on the shores of Kiparissia Bay, Greece, in 1987. Mésogée 48:59–65

Martins R, Marco A, Patino-Martinez J, Yeoman K, Vinagre C, Patrício AR (2022a) Ghost crab predation of loggerhead turtle eggs across thermal habitats. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 551:151735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2022.151735

Martins S, Patino – Martinez J, Abella E, Santos Loureiro N, Clarke LJ, Marco A (2022b) Potential impacts of sea level rise and beach flooding on reproduction of sea turtles. Clim Chang Ecol 3:100053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecochg.2022.100053

Maurer AS, Seminoff JA, Layman CA, Stapleton SP, Godfrey MH, Reiskind MOB (2021) Population viability of sea turtles in the context of global warming. Bioscience 71:790–804. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biab028

Montero N, Ceriani SA, Graham K, Fuentes MMPB (2018) Influences of the local climate on loggerhead hatchling production in North Florida: implications from climate change. Front Mar Sci 5:262. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00262

Mortimer JA, Carr A (1987) Reproduction and migrations of the Ascension Island green turtle (Chelonia mydas). Copeia 103–113. https://doi.org/10.2307/1446043

National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center (2008) Sea Turtle Research Techniques Manual. NOAA Tech Memo NMFS-SEFSC-579, p 92

Nordberg EJ, Macdonald S, Zimny G, Hoskins A, Zimny A, Somaweera R, Ferguson J, Perry J (2019) An evaluation of nest predator impacts and the efficacy of plastic meshing on marine turtle nests on the western Cape York Peninsula, Australia. Biol Conserv 238:108201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108201

O’Connor JM, Limpus CJ, Hofmeister KM, Allen BL, Burnett SE (2017) Anti-predator meshing may provide greater protection for sea turtle nests than predator removal. PLoS ONE 12:e0171831. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171831

Ocana M, Harfush-Melendez M, Heppell S (2012) Mass nesting of olive Ridley sea turtles Lepidochelys olivacea at La Escobilla, Mexico: linking nest density and rates of destruction. Endanger Species Res 16:45–54. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00388

Patrício A, Marques A, Barbosa C, Broderick A, Godley B, Hawkes L, Rebelo R, Regalla A, Catry P (2017) Balanced primary sex ratios and resilience to climate change in a major sea turtle population. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 577:189–203. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12242

Patrício AR, Varela MR, Barbosa C, Broderick AC, Ferreira Airaud MB, Godley BJ, Regalla A, Tilley D, Catry P (2018) Nest site selection repeatability of green turtles, Chelonia mydas, and consequences for offspring. Anim Behav 139:91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2018.03.006

Patrício AR, Varela MR, Barbosa C, Broderick AC, Catry P, Hawkes LA, Regalla A, Godley BJ (2019) Climate change resilience of a globally important sea turtle nesting population. Glob Chang Biol 25:522–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14520

Pike DA (2014) Forecasting the viability of sea turtle eggs in a warming world. Glob Chang Biol 20:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12397

Pulliam HR (1988) Sources, sinks, and population regulation. Am Nat 132:652–661

Pulliam HR, Danielson BJ (1991) Sources, sinks, and habitat selection: a landscape perspective on population dynamics. Am Nat 137:S50–S66. https://doi.org/10.1086/285139

Raposo C, Mestre J, Rebelo R, Regalla A, Davies A, Barbosa C, Patrício A (2023) Spatial distribution of inter-nesting green turtles from the largest Eastern Atlantic rookery and overlap with a marine protected area. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 703:161–175. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14225

Refsnider JM, Janzen FJ (2010) Putting eggs in one basket: ecological and evolutionary hypotheses for variation in oviposition-site choice. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 41:39–57. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144712

Sampaio MS, Rebelo R, Regalla A, Barbosa C, Catry P (2022) How to reduce the risk of predation of green turtle nests by nile monitors. Chelonian Conserv Biol 21:266–271. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1553.1

Santidrián-Tomillo P, Robinson NJ, Fonseca LG, Quirós-Pereira W, Arauz R, Beange M, Piedra R, Vélez E, Paladino FV, Spotila JR, Wallace BP (2017) Secondary nesting beaches for leatherback turtles on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Lat Am J Aquat Res 45:563–571. https://doi.org/10.3856/vol45-issue3-fulltext-6

Santos KC, Livesey M, Fish M, Lorences AC (2017) Climate change implications for the nest site selection process and subsequent hatching success of a green turtle population. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 22:121–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-015-9668-6

Schofield G, Hobson VJ, Lilley MKS, Katselidis KA, Bishop CM, Brown P, Hays GC (2010) Inter-annual variability in the home range of breeding turtles: implications for current and future conservation management. Biol Conserv 143:722–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.12.011

Shimada T, Duarte CM, Al-Suwailem AM, Tanabe LK, Meekan MG (2021) Satellite tracking reveals nesting patterns, site fidelity, and potential impacts of warming on major green turtle rookeries in the Red Sea. Front Mar Sci 8:633814. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.633814

Silva R, Martínez ML, van Tussenbroek BI, Guzmán-Rodríguez LO, Mendoza E, López-Portillo J (2020) A framework to manage coastal squeeze. Sustainability 12:10610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410610

Siqueira SCW, Gonçalves RM, Queiroz HAA, Pereira PS, Silva AC, Costa MB (2021) Understanding the coastal erosion vulnerability influence over sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting in NE of Brazil. Reg Stud Mar Sci 47:101965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2021.101965

Statements & Declarations

Stiebens VA, Merino SE, Roder C, Chain FJJ, Lee PLM, Eizaguirre C (2013) Living on the edge: how philopatry maintains adaptive potential. Proc R Soc B 280:20130305. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.0305

Stokes HJ, Esteban N, Hays GC (2024) Predation of sea turtle eggs by rats and crabs. Mar Biol 171:17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-023-04327-9

Tiwari M, Bjorndal KA, Bolten AB, Bolker BM (2006) Evaluation of density-dependent processes and green turtle Chelonia mydas hatchling production at Tortuguero, Costa Rica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 326:283–293. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps326283

Tiwari M, Balazs GH, Hargrove S (2010) Estimating carrying capacity at the green turtle nesting beach of East Island, French Frigate shoals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 419:289–294. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08833

Turkozan O, Yamamoto K, Yılmaz C (2011) Nest site preference and hatching success of green (Chelonia mydas) and loggerhead (Caretta caretta) sea turtles at Akyatan Beach, Turkey. Chelonian Conserv Biol 10:270–275. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-0861.1

Varela MR, Patrício AR, Anderson K, Broderick AC, DeBell L, Hawkes LA, Tilley D, Snape RTE, Westoby MJ, Godley BJ (2019) Assessing climate change associated sea-level rise impacts on sea turtle nesting beaches using drones, photogrammetry and a novel GPS system. Glob Chang Biol 25:753–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14526

Welbergen JA, Meade J, Field HE, Edson D, McMichael L, Shoo LP, Praszczalek J, Smith C, Martin JM (2020) Extreme mobility of the world’s largest flying mammals creates key challenges for management and conservation. BMC Biol 18:101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00829-w

Whytlaw PA, Edwards W, Congdon BC (2013) Marine turtle nest depredation by feral pigs (Sus scrofa) on the Western Cape York Peninsula Australia: implications for management. Wildl Res 40:377–384. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR12198

Wilson DS (1998) Nest-site selection: microhabitat variation and its effects on the survival of turtle embryos. Ecology 79:1884–1892. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1884:NSSMVA]2.0.CO;2

Witherington BE (1999) Reducing threats to nesting habitat. In: Eckert KL, Bjorndal KA, Abreu-Grobois FA, Donelly M (eds) Research and Management techniques for the conservation of Sea turtles, vol 4. IUCN/SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group Publication, pp 179–183

Wood DW, Bjorndal KA (2000) Relation of temperature, moisture, salinity, and slope to nest site selection in loggerhead sea turtles. Copeia 1:119–128. https://doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2000)2000[0119:ROTMSA]2.0.CO;2

Zárate P, Bjorndal K, Parra M, Dutton P, Seminoff J, Bolten A (2013) Hatching and emergence success in green turtle Chelonia mydas nests in the Galápagos Islands. Aquat Biol 19:217–229. https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00534

Acknowledgements

We thank the Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas (IBAP), Dr. Alfredo Simão da Silva of Guinea-Bissau for providing access to data from the long-term monitoring program in the Bijagós Archipelago. Research permits were issued by IBAP. Field protocols were carefully performed to lessen disturbance to sea turtles (NMFS-SFC 2008) and followed all institutional guidelines. Nesting turtles were handled to the strictly necessary and hatchlings were released immediately after nest excavations or kept inside buckets with moist sand from the nests and released close to the shoreline after sunset. We acknowledge IBAP technicians and rangers, and the Bijagós community members, among other people, who were involved in the nesting turtle surveys. This study was funded by: the MAVA Foundation through the project “Consolidation of sea turtle conservation at the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau”; the Regional Partnership for Coastal and Marine Conservation (PRCM), through the project “Survie des Tortues Marines”; the “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) through a fellowship awarded to ARP (LCF/BQ/PR20/11770003); and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal, through a grant (UIDB/04292/2020 and UIDP/04292/2020) awarded to MARE, the project LA/P/0069/2020 granted to the Associate Laboratory ARNET, the grant UIDB/00329/2020 with DOI https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00329/2020 awarded to Centro de Ecologia, Evolução e Alterações Ambientais; and a PhD grant (2020.08549.BD) awarded to CR.

Funding

This study was funded by: the MAVA Foundation through the project “Consolidation of sea turtle conservation at the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau”; the Regional Partnership for Coastal and Marine Conservation (PRCM), through the project “Survie des Tortues Marines”; the “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) through a fellowship awarded to ARP (LCF/BQ/PR20/11770003); and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal, through a grant (UIDB/04292/2020 and UIDP/04292/2020) awarded to MARE, the project LA/P/0069/2020 granted to the Associate Laboratory ARNET, the grant UIDB/00329/2020 with DOI https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00329/2020 awarded to Centro de Ecologia, Evolução e Alterações Ambientais; and a PhD grant (2020.08549.BD) awarded to CR.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CR, RR, PC and ARP conceived the study. MBFA, CB, TBG and MSS conducted the fieldwork. CR, MBFA, TBG and MSS led the data analysis. AR facilitated fieldwork logistics and research permits. CR wrote the initial draft of the article. RR, PC and ARP reviewed different versions of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author CR declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author RR declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author PC declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author MBFA declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author CB declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author TGB declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author AR declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author MSS declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author ARP declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Research permits were issued by the Instituto da Biodiversidade e das Áreas Protegidas (IBAP), Dr. Alfredo Simão da Silva of Guinea-Bissau. Field protocols were carefully performed to lessen disturbance to sea turtles (National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 2008) and followed all institutional guidelines. Nesting turtles were handled to the strictly necessary and hatchlings were released immediately after nest excavations or kept inside buckets with moist sand from the nests and released close to the shoreline after sunset.

Additional information

Communicated by L. Avens.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raposo, C., Rebelo, R., Catry, P. et al. Inter-island nesting dynamics and clutch survival of green turtles Chelonia mydas within a marine protected area in the Bijagós Archipelago, West Africa. Mar Biol 171, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-024-04463-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-024-04463-w