Abstract

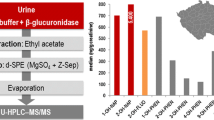

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are ubiquitous pollutants formed during the incomplete combustion of organic matter such as tobacco. Among these, benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) has been classified as a known carcinogen to humans. It unfolds its effect through metabolic activation to BaP-(7R,8S)-diol-(9S,10R)-epoxide (BPDE), the ultimate carcinogen of BaP. In this article, we describe a simple and highly sensitive GC–NICI–MS/MS method for the quantification of urinary BaP-(7R,8S,9R,10S)-tetrol (( +)-BPT I-1), the hydrolysis product of BPDE. The method was validated and showed excellent results in terms of accuracy, precision, and sensitivity (lower limit of quantification (LLOQ): 50 pg/L). In urine samples derived from users of tobacco/nicotine products and non-users, only consumption of combustible cigarettes was associated with a significant increase in BPT I-1 concentrations (0.023 ± 0.016 nmol/mol creatinine, p < 0.001). Levels of users of potentially reduced-risk products as well as non-users were all below the LLOQ. In addition, the urine levels of six occupationally exposed workers were analyzed and showed the highest overall concentrations of BPT I-1 (844.2 ± 336.7 pg/L). Moreover, comparison with concentrations of 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene (3-OH-BaP), the major detoxification product of BaP oxidation, revealed higher levels of 3-OH-BaP than BPT I-1 in almost all study subjects. Despite the lower levels, BPT I-1 can provide more relevant information on an individual’s cancers susceptibility since BPDE is generated by the metabolic activation of BaP. In conclusion, BPT I-1 is a suitable biomarker to distinguish not only cigarette smokers from non-smokers but also from users of potentially reduced-risk products.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AMS:

-

Accelerator mass spectrometry

- APLI:

-

Atmospheric pressure laser ionization

- Bap:

-

Benzo[a]pyrene

- BPT I-1:

-

trans, anti-Benzo[a]pyrene tetrol

- BPT I-2:

-

cis, anti-Benzo[a]pyrene tetrol

- BPT II-1:

-

trans, syn-Benzo[a]pyrene tetrol

- BPT II-2:

-

cis, syn-Benzo[a]pyrene tetrol

- BPDE :

-

Benzo[a]pyrene-(7R,8S)-diol-(9S,10R)-epoxide

- reverse-BPDE :

-

Benzo[a]pyrene -(9S,10R)-diol-(7R,8S)-epoxide

- CV :

-

Coefficient of variation

- CC :

-

Combustible cigarette

- CE:

-

Collision energy

- CYP :

-

Cytochrome P450

- EC:

-

Electronic cigarette

- EH :

-

Epoxide hydrolase

- FMV:

-

First morning void

- GC:

-

Gas chromatography

- HTP :

-

Heated tobacco product

- HBM :

-

Human biomonitoring

- 3-OH-BaP :

-

3-Hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene

- IS :

-

Internal standard

- IQR :

-

Interquartile range

- LLOQ :

-

Lower limit of quantification

- LOD :

-

Limit of detection

- MS :

-

Mass spectrometry

- NICI :

-

Negative ion chemical ionization

- NRT :

-

Nicotine replacement therapy

- NU :

-

Non-users

- OT :

-

Oral tobacco

- PAH :

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

- PTV :

-

Programmed temperature vaporization

- QC :

-

Quality control

- MS/MS :

-

Tandem mass spectrometry

- TMS :

-

Trimethylsilyl

- UHPLC :

-

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography

- ULOQ :

-

Upper limit of quantification

References

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;92:1–853.

Simoneit BRT. Biomass burning — a review of organic tracers for smoke from incomplete combustion. Appl Geochem. 2002;17(3):129–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-2927(01)00061-0.

Kamal A, Cincinelli A, Martellini T, Malik RN. A review of PAH exposure from the combustion of biomass fuel and their less surveyed effect on the blood parameters. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22(6):4076–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3748-0.

Srogi K. Monitoring of environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2007;5(4):169–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-007-0095-0.

Rodgman A, Perfetti TA. The composition of cigarette smoke: a catalogue of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Beitr Tab Int. 2006;22(1):13–69. https://doi.org/10.2478/cttr-2013-0817.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Polynuclear aromatic compounds, part 1. Chemical, environmental and experimental data. IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of chemicals to humans. 32. Lyon, France: IARC. 1983. pp. 419–30.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. IARC Sci Publ. 2012;100:385.

Brandt HC, Watson WP. Monitoring human occupational and environmental exposures to polycyclic aromatic compounds. Ann Occup Hyg. 2003;47(5):349–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/meg052.

Schick SF, Blount BC, Jacob PR, Saliba NA, Bernert JT, El Hellani A, et al. Biomarkers of exposure to new and emerging tobacco delivery products. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;313(3):L425–52. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00343.2016.

Zurita J, Motwani HV, Ilag LL, Souliotis VL, Kyrtopoulos SA, Nilsson U, et al. Detection of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide adducts to histidine and lysine in serum albumin in vivo by high-resolution-tandem mass spectrometry. Toxics. 2022;10(1) https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10010027.

Bukowska B, Mokra K, Michalowicz J. Benzo[a]pyrene-environmental occurrence, human exposure, and mechanisms of toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11) https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23116348.

Nisbet IC, LaGoy PK. Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1992;16(3):290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2300(92)90009-X.

Xue W, Warshawsky D. Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206(1):73–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006.

Angerer J, Mannschreck C, Gundel J. Biological monitoring and biochemical effect monitoring of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1997;70(6):365–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004200050231.

Hecht SS, Hochalter JB. Quantitation of enantiomers of r-7, t-8,9, c-10-tetrahydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]-pyrene in human urine: evidence supporting metabolic activation of benzo[a]pyrene via the bay region diol epoxide. Mutagenesis. 2014;29(5):351–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/geu024.

Zhong Y, Carmella SG, Hochalter JB, Balbo S, Hecht SS. Analysis of r-7, t-8,9, c-10-tetrahydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene in human urine: a biomarker for directly assessing carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure plus metabolic activation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(1):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx100287n.

Rögner N, Hagedorn H-W, Scherer G, Scherer M, Pluym N. A sensitive LC–MS/MS method for the quantification of 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene in urine-exposure assessment in smokers and users of potentially reduced-risk products. Separations. 2021;8(10):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations8100171.

Barbeau D, Lutier S, Bonneterre V, Persoons R, Marques M, Herve C, et al. Occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: relations between atmospheric mixtures, urinary metabolites and sampling times. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(8):1119–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1042-1.

Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Henderson CJ, Thiemann M, Frei E, Aimova D, et al. Metabolic activation of benzo[a]pyrene in vitro by hepatic cytochrome P450 contrasts with detoxification in vivo: experiments with hepatic cytochrome P450 reductase null mice. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(3):656–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgn002.

Thakker DR, Yagi H, Lu AY, Levin W, Conney AH. Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene: conversion of (+/-)-trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene to highly mutagenic 7,8-diol-9,10-epoxides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73(10):3381–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.73.10.3381.

Villalta PW. Balbo SJIjoms. The future of DNA adductomic analysis. 2017;18(9):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18091870.

Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(6):622–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.20495.

Kafferlein HU, Marczynski B, Mensing T, Bruning T. Albumin and hemoglobin adducts of benzo[a]pyrene in humans—analytical methods, exposure assessment, and recommendations for future directions. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2010;40(2):126–50. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408440903283633.

Day BW, Skipper PL, Rich RH, Naylor S, Tannenbaum SR. Conversion of a hemoglobin α chain aspartate (47) ester to N-(2, 3-dihydroxypropyl) asparagine as a method for identification of the principal binding site for benzo[a]pyrene anti-diol epoxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4(3):359–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx00021a016.

Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Villalta PW, Hochalter JB. Analysis of phenanthrene and benzo[a]pyrene tetraol enantiomers in human urine: relevance to the bay region diol epoxide hypothesis of benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenesis and to biomarker studies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(5):900–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx9004538.

Hochalter JB, Zhong Y, Han S, Carmella SG, Hecht SS. Quantitation of a minor enantiomer of phenanthrene tetraol in human urine: correlations with levels of overall phenanthrene tetraol, benzo[a]pyrene tetraol, and 1-hydroxypyrene. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(2):262–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx100391z.

Simpson CD, Wu MT, Christiani DC, Santella RM, Carmella SG, Hecht SS. Determination of r-7, t-8,9, c-10-tetrahydroxy-7,8,9, 10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene in human urine by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization/mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13(4):271–80. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx990202c.

Grova N, Hardy EM, Meyer P, Appenzeller BM. Analysis of tetrahydroxylated benzo[a]pyrene isomers in hair as biomarkers of exposure to benzo[a]pyrene. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(8):1997–2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-9338-x.

Luo K, Gao Q, Hu J. Determination of 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene glucuronide/sulfate conjugates in human urine and their association with 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2019;32(7):1367–73. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00025.

Steward AR, Zaleski J, Sikka HC. Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene and (-)-trans-benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol by freshly isolated hepatocytes of brown bullheads. Chem Biol Interact. 1990;74(1–2):119–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2797(90)90063-s.

Barbeau D, Lutier S, Choisnard L, Marques M, Persoons R, Maitre A. Urinary trans-anti-7,8,9,10-tetrahydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo(a)pyrene as the most relevant biomarker for assessing carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure. Environ Int. 2018;112:147–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.12.012.

Jongeneelen FJ. Methods for routine biological monitoring of carcinogenic PAH-mixtures. Sci Total Environ. 1997;199(1–2):141–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-9697(97)00064-8.

Hilton DC, Trinidad DA, Hubbard K, Li Z, Sjodin A. Measurement of urinary Benzo[a]pyrene tetrols and their relationship to other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites and cotinine in humans. Chemosphere. 2017;189:365–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.077.

Dennis MJ, Massey RC, Cripps G, Venn I, Howarth N, Lee G. Factors affecting the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content of cereals, fats and other food products. Food Addit Contam. 1991;8(4):517–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652039109374004.

Lee HL, Hsieh DP, Li LA. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette sidestream smoke particulates from a Taiwanese brand and their carcinogenic relevance. Chemosphere. 2011;82(3):477–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.09.045.

Khalili NR, Scheff PA, Holsen TM. PAH source fingerprints for coke ovens, diesel and gasoline engines, highway tunnels, and wood combustion emissions. Atmos Environ. 1995;29(4):533–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/1352-2310(94)00275-p.

St Charles FK, McAughey J, Shepperd CJ. Methodologies for the quantitative estimation of toxicant dose to cigarette smokers using physical, chemical and bioanalytical data. Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25(7):383–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2013.794177.

Richter-Brockmann S, Dettbarn G, Jessel S, John A, Seidel A, Achten C. GC-APLI-MS as a powerful tool for the analysis of BaP-tetraol in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2018;1100–1101:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.08.006.

Sibul F, Burkhardt T, Kachhadia A, Pilz F, Scherer G, Scherer M, et al. Identification of biomarkers specific to five different nicotine product user groups: study protocol of a controlled clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2021;22: 100794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100794.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Bioanalytical method validation—guidance for industry: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/bioanalytical-method-validation-guidance-industry. Accessed 31.08.2023.

World Medical A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

Blaszkewicz M, Liesenhoff‐Henze K. Creatinine in urine. In: Hartwig A, Angerer J, editors. Biomonitoring methods (part IV). The MAK-collection for occupational health and safety: annual thresholds and classifications for the workplace. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. 2010. pp. 169–84.

Committee AM. What should be done with results below the detection limit? Mentioning the unmentionable. Royal Society of Chemistry. 2001;126(5):256–9.

Bergstrand M, Karlsson MO. Handling data below the limit of quantification in mixed effect models. AAPS J. 2009;11(2):371–80. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-009-9112-5.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Management of left‐censored data in dietary exposure assessment of chemical substances. EFSA J. 2010;8(3):1557.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria:R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vol.13 No.2, April 12, 2023. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA:RStudio, PBC. 2023. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4(43):1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686.

Kassambara A. rstatix: pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. R package version 0.7. 0. 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstatix/index.html. Accessed 09.09.2023.

Müller K. here: a simpler way to find your files. 2019. https://here.r-lib.org/. Accessed 13.12.2023.

Wilke CO. Streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for “ggplot2” [R Package Cowplot Version 1.1.1]. 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cowplot/index.html. Accessed 03.12.2023.

Upadhyaya P, Hochalter JB, Balbo S, McIntee EJ, Hecht SS. Preferential glutathione conjugation of a reverse diol epoxide compared with a bay region diol epoxide of benzo[a]pyrene in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(9):1397–402. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.110.034181.

Grova N, Salquebre G, Hardy EM, Schroeder H, Appenzeller BM. Tetrahydroxylated-benzo[a]pyrene isomer analysis after hydrolysis of DNA-adducts isolated from rat and human white blood cells. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1364:183–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2014.08.082.

Barbeau D, Maitre A, Marques M. Highly sensitive routine method for urinary 3-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene quantitation using liquid chromatography-fluorescence detection and automated off-line solid phase extraction. Analyst. 2011;136(6):1183–91. https://doi.org/10.1039/c0an00428f.

Barbeau D, Lutier S, Marques M, Persoons R, Maitre A. Comparison of gaseous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites according to their specificity as biomarkers of occupational exposure: selection of 2-hydroxyfluorene and 2-hydroxyphenanthrene. J Hazard Mater. 2017;332:185–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.03.011.

Bourgart E, Barbeau D, Marques M, von Koschembahr A, Beal D, Persoons R, et al. A realistic human skin model to study benzo[a]pyrene cutaneous absorption in order to determine the most relevant biomarker for carcinogenic exposure. Arch Toxicol. 2019;93(1):81–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-018-2329-2.

Klaene JJ, Sharma VK, Glick J, Vouros P. The analysis of DNA adducts: the transition from (32)P-postlabeling to mass spectrometry. Cancer Lett. 2013;334(1):10–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.007.

Poirier MC, Santella RM, Weston A. Carcinogen macromolecular adducts and their measurement. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):353–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/21.3.353.

Villalta PW, Hochalter JB, Hecht SS. Ultrasensitive high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis of a DNA adduct of the carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene in human lung. Anal Chem. 2017;89(23):12735–42. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02856.

Vermillion Maier ML, Siddens LK, Pennington JM, Uesugi SL, Anderson KA, Tidwell LG, et al. Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) metabolites predominant in human plasma following escalating oral micro-dosing with [14C]-BaP. Environ Int. 2022;159: 107045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.107045.

Olsen R, Sagredo C, Ovrebo S, Lundanes E, Greibrokk T, Molander P. Determination of benzo[a]pyrene tetrols by column-switching capillary liquid chromatography with fluorescence and micro-electrospray ionization mass spectrometric detection. Analyst. 2005;130(6):941–7. https://doi.org/10.1039/b419145e.

Koeber R, Niessner R, Bayona JM. Comparison of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry interfaces for the analysis of polar metabolites of benz[a]pyrene. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 1997;359(3):267–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002160050571.

Xia Q, Chiang HM, Yin JJ, Chen S, Cai L, Yu H, et al. UVA photoirradiation of benzo[a]pyrene metabolites: induction of cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation. Toxicol Ind Health. 2015;31(10):898–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233713484648.

Weston A, Bowman ED, Carr P, Rothman N, Strickland PT. Detection of metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human urine. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(5):1053–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/14.5.1053.

Maier MLV, Siddens LK, Pennington JM, Uesugi SL, Labut EM, Vertel EA, et al. Impact of phenanthrene co-administration on the toxicokinetics of benzo[a]pyrene in humans. UPLC-accelerator mass spectrometry following oral microdosing. Chem Biol Interact. 2023;382:110608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110608.

Scherer G, Scherer M, Rogner N, Pluym N. Assessment of the exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in users of various tobacco/nicotine products by suitable urinary biomarkers. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96(11):3113–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-022-03349-4.

Scherer G, Pluym N, Scherer M. Intake and uptake of chemicals upon use of various tobacco/nicotine products: can users be differentiated by single or combinations of biomarkers? Contr Tob Nicotine Res. 2021;30(4):167–98. https://doi.org/10.2478/cttr-2021-0014.

Ding YS, Trommel JS, Yan XJ, Ashley D, Watson CH. Determination of 14 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream smoke from domestic cigarettes. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39(2):471–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/es048690k.

Heidelberger C, Weiss SM. The distribution of radioactivity in mice following administration of 3, 4-benzpyrene-5-C14 and 1, 2, 5, 6-dibenzanthracene-9, 10–C14. Cancer Res. 1951;11(11):885–91.

Jacob J, Seidel A. Biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;778(1–2):31–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00467-4.

Hecht SS, Grabowski W, Groth K. Analysis of faeces for benzo[a]pyrene after consumption of charcoal-broiled beef by rats and humans. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1979;17(3):223–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0015-6264(79)90284-0.

Chu I, Ng K, Benoit F, Moir D. Comparative metabolism of phenanthrene in the rat and guinea pig. J Environ Sci Health B. 1992;27(6):729–49.

Wu MT, Simpson CD, Christiani DC, Hecht SS. Relationship of exposure to coke-oven emissions and urinary metabolites of benzo(a)pyrene and pyrene in coke-oven workers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(3):311–4.

Aylward LL, Hays SM, Smolders R, Koch HM, Cocker J, Jones K, et al. Sources of variability in biomarker concentrations. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2014;17(1):45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2013.864250.

Aylward LL, Kirman CR, Adgate JL, McKenzie LM, Hays SM. Interpreting variability in population biomonitoring data: role of elimination kinetics. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22(4):398–408. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2012.35.

Moreau M, Bouchard M. Comparison of the kinetics of various biomarkers of benzo[a]pyrene exposure following different routes of entry in rats. J Appl Toxicol. 2015;35(7):781–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.3070.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alpeshkumar Kachhadia and Therese Burkhardt for their support and for contributing to helpful scientific discussions. We thank Nadine Rögner and Marta Latawiec for the measurement of 3-OH-BaP, Michael Sprenzel for measuring creatinine values, and Kira Pormann for support with the study sample analysis.

Funding

This study was funded with a grant from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. The Foundation for a Smoke-Free World is an independent, US nonprofit 501(c)(3) grantmaking organization with the purpose of improving global health by ending smoking in this generation. Through September 2023, the Foundation received charitable gifts from PMI Global Services Inc. (“PMI”). Independent from PMI since its founding in 2017, the Foundation operates in a manner that ensures its independence from PMI and any commercial entity. The Foundation seeks to collaborate with associations and institutions to accelerate its investments in life-saving research projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.P., N.P., G.S., and M.S. Methodology: F.P., N.P., and M.S. Formal analysis and investigation: F.P. and A.G. Validation: F.P. and A.G.; Visualization: F.P. Writing—original draft preparation: F.P. Writing—review and editing: M.S. and F.P. Funding acquisition: M.S. Supervision: M.S. and N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

A clinical study was conducted at the Clinical Trial Center (CTC) North (Hamburg, Germany) [39]. For all collected study samples, ethical approval was received according to the Helsinki declaration by the Ethical Commission of the Medical Chamber of Hamburg (Germany).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial as well as nonfinancial interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pilz, F., Gärtner, A., Pluym, N. et al. A sensitive GC–MS/MS method for the quantification of benzo[a]pyrene tetrol in urine. Anal Bioanal Chem 416, 2913–2928 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-024-05233-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-024-05233-9