Abstract

In this work, we study codes generated by elements that come from group matrix rings. We present a matrix construction which we use to generate codes in two different ambient spaces: the matrix ring \(M_k(R)\) and the ring R, where R is the commutative Frobenius ring. We show that codes over the ring \(M_k(R)\) are one sided ideals in the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G\) and the corresponding codes over the ring R are \(G^k\)-codes of length kn. Additionally, we give a generator matrix for self-dual codes, which consist of the mentioned above matrix construction. We employ this generator matrix to search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12] and find new singly-even and doubly-even codes of this type. In particular, we construct 16 new Type I and 4 new Type II binary [72, 36, 12] self-dual codes.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Self-dual codes are one of the most widely studied and interesting class of codes. They have been shown to have strong connections to unimodular lattices, invariant theory, and designs. In particular, binary self-dual codes have been extensively studied and numerous construction techniques of self-dual codes have been used in an attempt to find optimal self-dual codes.

In this work, we give a new construction of self-dual codes motivated by the constructions given in [6] and [11]. In our construction, we use group rings where the ring is a ring of matrices to construct generator matrices of self-dual codes. The main point of this construction is to find codes that other techniques have missed. We construct numerous new self-dual codes using this technique.

We begin with some definitions. A code C over an alphabet A of length n is a subset of \(A^n\). We say that the code is linear over A if A is a ring and C is a submodule. This implies that when A is a finite field, then C is a vector space. We attach to the ambient space the standard Euclidean inner-product, that is \([{\mathbf {v}},{\mathbf {w}}] = \sum v_i w_i\). When A is commutative, we define the orthogonal to this inner-product as \(C^\perp = \{ {\mathbf {w}}\ | [{\mathbf {w}},{\mathbf {v}}]=0, \forall {\mathbf {v}}\in C \}.\) If the ring A is not commutative, then we say that the code is either left linear or right linear depending if it is a left or right module. In this scenario, we have two orthogonals, namely \({\mathcal{L}}(C) = \{ {\mathbf {w}}\ | \ [{\mathbf {w}},{\mathbf {v}}]=0, \forall {\mathbf {v}}\in C \}\) and \({\mathcal{R}}(C) = \{ {\mathbf {w}}\ | \ [{\mathbf {v}},{\mathbf {w}}]=0, \forall {\mathbf {v}}\in C \}.\) If the ring is not commutative then these two codes are not necessarily equal, and in general will not be. Moreover, \({\mathcal{L}}(C)\) is a left linear code and \({\mathcal{R}}(C)\) is a right linear code. If the ring is commutative, then \(\mathcal{L}(C) = \mathcal{R}(C) = C^\perp .\) It is known that if C is a left linear code over a Frobenius ring A then \(|C| |{\mathcal{R}}(C) | = |A^n|\) and if C is a right linear code over a Frobenius ring A then \(|C| |{\mathcal{L}}(C) | = |A^n|.\) For commutative rings, this gives that \(|C||C^\perp |=|A^n|.\) For a complete description of codes over commutative rings see [4]. For a description of codes over non-commutative rings see [5]. Throughout this work we assume that every ring has a multiplicative identity and is finite.

Later in this work, we construct binary self-dual codes. For this reason, we now recall the following. An upper bound on the minimum Hamming distance of a binary self-dual code was given in [15]. Specifically, let \(d_{I}(n)\) and \(d_{II}(n)\) be the minimum distance of a Type I (singly-even) and Type II (doubly-even) binary code of length n, respectively. Then

and

Self-dual codes meeting these bounds are called extremal.

In this work, we shall use the theory of group rings to build codes. We shall give the necessary definitions for this study. Let R be a ring, then if R has an identity \(1_R,\) we say that \(u \in R\) is a unit in R if and only if there exists an element \(w \in R\) with \(uw=1_R.\) Let G be a finite group of order n, then the group ring RG consists of \(\sum _{i=1}^n \alpha _i g_i\), \(\alpha _i \in R\), \(g_i \in G.\)

Addition in the group ring is done by coordinate addition, namely

The product of two elements in a group ring is given by

This gives that the coefficient of \(g_k\) in the product is \(\sum _{g_i g_j = g_k } \alpha _i \beta _j .\) Notice, that while group rings can use rings and groups of arbitrary cardinality, we restrict ourselves to finite groups and finite rings. Note that we have not assumed that group nor the ring is commutative.

The space of k by k matrices with coefficients in the ring R is denoted by \(M_k(R).\) It is immediate that \(M_k(R)\) is a ring, however, it is, in general, a non-commutative ring. Moreover, it is fundamental in the study of non-commutative rings since any finite ring moded out by its Jacobson radical is isomorphic to a direct product of matrix rings. Moreover, we know that \(M_k(R)\) is a Frobenius ring, when R is Frobenius.

A circulant matrix is one where each row is shifted one element to the right relative to the preceding row. We label the circulant matrix as \(circ(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\dots , \alpha _n),\) where \(\alpha _i\) are ring elements appearing in the first row. A reverse-circulant matrix is one where each row is shifted one element to the left relative to the preceding row. We label the reverse-circulant matrix as \(revcirc(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\dots ,\alpha _n),\) where \(\alpha _i\) are ring elements appearing in the first row. A block-circulant matrix is one where each row contains blocks which are square matrices. The rows of the block matrix are defined by shifting one block to the right relative to the preceding row. We label the block-circulant matrix as \(\text{CIRC}(A_1,A_2,\dots , A_n),\) where \(A_i\) are \(k \times k\) matrices over the ring R appearing in the first row. The transpose of a matrix A, denoted by \(A^T,\) is a matrix whose rows are the columns of A, i.e., \((A^T)_{ij}=A_{ji}.\) A symmetric matrix is a square matrix that is equal to its transpose. A persymmetric matrix is a square matrix which is symmetric with respect to the north-east-to-south-west diagonal.

2 Matrix construction from group matrix rings

The following construction of a matrix which was used to construct codes that were ideals in a group ring was first given for codes over fields by Hurley in [11]. It was then extended to finite commutative Frobenius rings in [6]. Let R be a finite commutative Frobenius ring and let \(G=\{g_1,g_2,\dots ,g_n\}\) be a group of order n. Let \(v=\alpha _{g_1}g_1+\alpha _{g_2}g_2+\dots +\alpha _{g_n}g_n \in RG.\) Define the matrix \(\sigma (v) \in M_n(R)\) to be

We note that the elements \(g_1^{-1}, g_2^{-1}, \dots , g_n^{-1}\) are the elements of the group G in a some given order.

This matrix was used as a generator matrix for codes. The form of the matrix guaranteed that the resulting code would correspond to an ideal in the group ring and thus have the group G as a subgroup of its automorphism group, that is the group G, acting on the coordinates, would leave the code fixed. The fundamental purpose of this was to construct codes that were not found using more traditional construction techniques. It was shown in [6] that certain classical constructions would only produce a subset of all possible codes (in this case self-dual codes) and would often miss codes that were of particular interest. With this in mind we are interested in expanding these kinds of constructions to enable us to find codes that would be missed with other construction techniques.

We now generalize the matrix construction just defined. Let R be a finite commutative ring and let \(G=\{g_1,g_2,\dots ,g_n\}\) be a group of order n. We note that no assumption about the groups commutativity is made. Let \(v=A_{g_1}g_1+A_{g_2}g_2+\dots +A_{g_n}g_n \in M_k(R)G,\) that is, each \(A_{g_i}\) is a \(k \times k\) matrix with entries from the ring R. Define the block matrix \(\sigma _k(v) \in M_n(M_k(R))\) to be

We note that the element v is an element of the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G.\) Of course, this is the same construction as was previously given for group rings but we specify it here since we will use it in very different ways. Namely, we can consider the matrix as generating two distinct codes in different ambient spaces.

This group matrix ring can be non-commutative in two ways. First, since the group may not be commutative, multiplication on the left by an element \(g \in G\) can give a different element than multiplication on the right by g. We note that in generating the matrix \(\sigma _k(v)\) the rows are formed from elements that were constructed by a group element multiplying on the left. Moreover, multiplication by an element \(B \in M_k(R)\) on the left can give a different element than multiplication on the right by B.

As in the matrix \(\sigma (v)\) from Eq. 2.1, the elements \(g_1^{-1}, g_2^{-1}, \dots , g_n^{-1}\) are the elements of the group G given in a some order. This order is used in order aid in the computational aspects of some proofs. We note that when \(k=1\) then \(\sigma _1(v)=\sigma (v),\) that is, \(\sigma _1(v)\) is equivalent to the matrix \(\sigma (v)\) in the original definition. In general, we shall often assume that \(k>1.\)

The next theorem sets up some useful algebraic tools.

Theorem 2.1

Let R be a finite commutative ring. Let G be a group of order n with a fixed listing of its elements. Then the map \(\sigma _k: M_k(R)G \rightarrow M_n(M_k(R))\) is a matrix ring homomorphism.

Proof

Let \(G=\{g_1,g_2,\dots ,g_n\}\) be the listing of the elements of G. Now define the map \(\sigma _k : M_k(R)G \rightarrow M_n(M_k(R))\) as follows. Suppose \(v=\sum _{i=1}^n A_{g_i}g_i.\) Then

where each \(A_{g_i}\) is a square matrix of order k. It can be easily verified that this mapping is additive. We now show that \(\sigma _k\) is multiplicative. Consider \(w=\sum _{i=1}^n B_{g_i}g_i\) then

Now suppose \(w * v=t,\) where \(t=\sum _{i=1}^n C_{g_i}g_i.\) Then

and this is \(\sigma _k(t)=\sigma _k(w * v)\) as required. \(\square\)

Let the first column of the matrix in Eq. (2.2) be labelled by \(g_1,\) the second column by \(g_2,\) etc. Then if \(b=\sum _{i=1}^n B_{g_i}g_i\) is in \(M_k(R)G\) then the coefficient of \(g_i\) in the product \(b * v\) is \((B_{g_1},B_{g_2},\dots ,B_{g_n})\) times the i-th column of \(\sigma _k(v).\) We note here that we are multiplying by b on the left. This could easily be done on the right to get a similar result.

We define the k by k matrix \(I_k\) in the usual way. That is \((I_k)_{ij} =1\) if \(i=j\) and \((I_k)_{ij} =0\) if \(i \ne j.\) Since each ring we consider in this paper has a multiplicative identity this matrix is always an element in \(M_k(R).\)

Theorem 2.2

Let R be a finite commutative ring. Then \(v \in M_k(R)G\) is a unit in \(M_k(R)G\) if and only if \(\sigma _k(v)\) is a unit in \(M_n(M_k(R)).\)

Proof

Suppose v is a unit in \(M_k(R)G\) and that w is its inverse. Then \(v * w=(I_k)_{M_k(R)G}\) and hence \(\sigma _k(v * w)=\sigma _k((I_k)_{M_k(R)G})=I_{kn},\) the identity matrix in \(M_n(M_k(R)) .\) Thus \(\sigma _k(v) * \sigma _k(w)=I_{kn}.\) Similarly, \(\sigma _k(w) * \sigma _k(v)=I_{kn}\) and so \(\sigma _k(v)\) is invertible in \(M_n(M_k(R)) .\)

Suppose now that \(\sigma _k(v)\) is a unit in \(M_n(M_k(R))\) and let N denote its inverse. Let \(v=\sum _{i=1}^n A_{g_i}g_i.\) Then

where each \(A_{g_i}\) is a square matrix of order k. Let \((B_1,B_2,\dots ,B_n)\) be the first row of N, where \(B_i\) are the square matrices each of order k. Then:

Now \(v=A_{g_1}g_1+A_{g_2}g_2+\dots +A_{g_n}g_n=A_{g_{i}^{-1}g_1}g_{i}^{-1}g_1+A_{g_{i}^{-1}g_2}g_{i}^{-1}g_2+\dots +A_{g_{i}^{-1}g_n}g_{i}^{-1}g_n,\) for each i, \(1 \le i \le n.\)

Define \(w=B_1g_{1}+B_2g_{2}+\dots +B_ng_{n}.\) Then:

Hence: \(v * w=(B_1g_{1}+B_2g_{2}+\dots +B_ng_{n})(A_{g_1}g_1+A_{g_2}g_2+\dots +A_{g_n}g_n)\) equals to:

and this is \(g_1\) from the above. Thus \(g_1^{-1} * w\) is the inverse of v and v is a unit in \(M_k(R)\). \(\square\)

3 Group matrix ring codes

In this section, we employ the matrix construction from the previous section to generate codes in two different ambient spaces. We make two distinct constructions.

Construction 1 For a given element \(v \in M_k(R)G,\) we define the following code over the matrix ring \(M_k(R)\):

Here the code is generated by taking the all left linear combinations of the rows of the matrix with coefficients in \(M_k(R).\)

Construction 2 For a given element \(v \in M_k(R)G,\) we define the following code over the ring R. Construct the matrix \(\tau _k(v)\) by viewing each element in a k by k matrix as an element in the larger matrix.

Here the code \(B_k(v)\) is formed by taking all linear combinations of the rows of the matrix with coefficients in R. In this case the ring over which the code is defined is commutative so it is both a left linear and right linear code.

The following lemma is immediate.

Lemma 3.1

Let R be a finite Frobenius ring and let G be a group of order n. Let \(v \in M_k(R)G\).

-

1.

The matrix \(\sigma _k(v)\) is an n by n matrix with elements from \(M_k(R)\) and the code \(C_k(v)\) is a length n code over \(M_k(R)\).

-

2.

The matrix \(\tau _k(v)\) is an nk by nk matrix with elements from R and the code \(B_k(v)\) is a length nk code over R.

We illustrate these construction techniques in the following example.

Example 3.2

Let

where the group \(\langle a,b \rangle \cong D_8,\) the dihedral group with 8 elements. Then \(\sigma _2(v)\) generates a code \(C_2(v)\) which is the ambient space \(M_2({{\mathbb {F}}}_2)^8.\)

The matrix

and \(\tau _2(v)\) can be row reduced to

It can be easily checked that \(B_2(v)\) is a binary self-dual code with parameters [16, 8, 4]. We also note that the code \(B_2(v)\) can be constructed from \(\sigma _2(v)\) where \(v \in {\mathbb {F}}_2(C_2 \times D_8)\) but this requires employing a group of order 16.

It is clear that the aim of this construction is to construct interesting binary self-dual codes. That is, over the matrix ring, the code constructed was trivial, however, over the binary field the code constructed was an interesting self-dual code.

It is apparent that this generalization opens up a new direction for new constructions of codes. This is because the matrix \(\tau _k(v)\) does not only depend on the ring elements and the finite group G as does the matrix \(\sigma _k(v)\), but rather \(\tau _k(v)\) also depends on the form of the matrices \(A_{g_i}.\) We note that the \(k \times k\) matrices \(A_{g_i}\) over R can each take a different form - this is the first advantage of our generalization over the matrix \(\sigma (v)\). We also note that the matrix \(\sigma _k(v)\) gives us more freedom for controlling the search field when finding a special family of codes since the matrices \(A_{g_i}\) do not have to be fully defined by the ring elements appearing in their first rows - and this is the second advantage of our generalization over the matrix \(\sigma (v).\)

Theorem 3.3

Let R be a finite commutative Frobenius ring, k a positive integer and G a finite group of order n. Let \(v \in M_k(R)G\). Let \(I_k(v)\) be the set of elements of \(M_k(R)G\) such that \(\sum A_ig_i \in I_k(v)\) if and only if \((A_1,A_2,\dots ,A_n) \in C_k(v).\) Then \(I_k(v)\) is a left ideal in \(M_k(R)G\).

Proof

Each row of \(\sigma _k(v)\) corresponds to an element of the form hv in \(M_k(R)G,\) where h is any element of G. That is, the multiplication by h is done from left. The sum of any two elements in I(v) corresponds exactly to the sum of the corresponding elements in \(C_k(v)\) and so \(I_k(v)\) is closed under addition.

Now we shall show when the product of an element in \(M_k(R)G\) and an element in \(I_k(v)\) is in \(I_k(v).\) Let \(w_1=\sum B_ig_i \in M_k(R)G,\) where \(B_i\) are the \(k \times k\) matrices. Then if \(w_2\) is a row in \(C_k(v),\) it is of the form \(\sum C_jh_jv.\) Then \(w_1w_2=\sum B_ig_i \sum C_jh_jv= \sum B_iC_jg_ih_jv\) which corresponds to an element in \(C_k(v)\) gives that the element is in \(I_k(v).\) Next, consider \(w_2w_1=\sum C_jh_jv \sum B_ig_i=\sum C_jh_jvB_ig_i\) which may not be an element in \(C_k(v).\) Thus, \(I_k(v)\) is a left ideal of \(M_k(R)G\). \(\square\)

Given this theorem, we know that any code \(C_k(v)\) has G as a subgroup of its automorphism group.

The above two results highlight the difference between group codes studied in [6] and the codes we explore in this work. Namely, in group codes it is the coordinates that are held invariant by the action of the group G and in the codes we study in this work, it is the blocks that are held invariant by the action of the group G. For this reason, from now on, we refer to codes \(C_k(v)\) as group matrix ring codes.

Now we show that the orthogonal of a group matrix ring code for some group G is also a group matrix ring code. Let \(J_k\) be a one-sided, left ideal in a group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G.\) Define \({\mathfrak {R}}(C)=\{ w \ | \ vw=0, \forall v \in J_k\}.\) It is immediate that \({\mathfrak {R}}(J_k)\) is a one-sided, right ideal of \(M_k(R)G.\)

Let \(v=A_{g_1}g_1+A_{g_2}g_2+\dots +A_{g_n}g_n \in M_k(R)G\) and \(C_k(v)\) be the corresponding group matrix ring code. Let \(\Psi : M_k(R)G \rightarrow (M_k(R))^n\) be the canonical map that sends \(A_{g_1}g_1+A_{g_2}g_2+\dots +A_{g_n}g_n\) to \((A_{g_1},A_{g_2},\dots ,A_{g_n}).\) Let \(J_k\) be the one-sided, left ideal \(\Psi ^{-1}(C).\) Let \({\mathbf {w}}=(B_1,B_2,\dots ,B_n) \in {{\mathfrak {R}}}(C).\) Then

This gives that

Let \(w=\Psi ^{-1}({\mathbf {w}})=\sum B_{g_i}g_i\) and define \(\overline{{\mathbf {w}}} \in M_k(R)G\) to be \(\overline{{\mathbf {w}}}=C_{g_1}g_1+C_{g_2}g_2+\dots +C_{g_n}g_n\) where

Then

Then \(g_j^{-1}g_ig_i^{-1}=g_j^{-1},\) hence this is the coefficient of \(g_j^{-1}\) in the product of \(\overline{{\mathbf {w}}}\) and \(g_j^{-1}v.\) This gives that \(\overline{{\mathbf {w}}} \in {\mathfrak {R}}(J_k)\) if and only if \({\mathbf {w}} \in {\mathfrak {R}}(C).\)

Let \(\phi : (M_k(R))^n \rightarrow M_k(R)G\) by \(\phi ({\mathbf {w}})=\overline{{\mathbf {w}}}.\) It is clear that \(\phi\) is a bijection between \({\mathfrak {R}}(C)\) and \({\mathfrak {R}}(\Psi ^{-1}(C)).\)

Theorem 3.4

Let \(C=C_k(v)\) be a group matrix ring code in \(M_k(R)\) formed from the element \(v \in M_k(R)G.\) Then \(\Psi ^{-1}({\mathfrak {R}}(C))\) is a one-sided, left ideal of \(M_k(R)G.\) Moreover, if \(C_k(v)\) is a left-linear matrix ring G-code with the elements of the group acting on the left then \({\mathfrak {R}}(C_k(v))\) is a right-linear matrix group G-code with the elements of the group acting on the right.

Proof

Follows from the above discussion. \(\square\)

We can now investigate the situation for the code \(B_k(v).\) We begin with a definition. Let G be a finite group of order n and R a finite Frobenius commutative ring. Let D be a code in \(R^{sn}\) where the coordinates can be partitioned into n sets of size s where each set is assigned an element of G. If the code D is held invariant by the action of multiplying the coordinate set marker by every element of G then the code D is called a quasi-group code of length ns and of index s.

Lemma 3.5

Let R be a finite Frobenius ring and let G be a finite group with \(v \in M_k(R)\). Then \(B_k(v)\) is a quasi-G-code of length nk and index k.

Proof

Let \(v \in M_k(R)G\) and let \({\mathbf {w}}\) be a row of the matrix \(\tau _k(v)\). Letting any element in G act on the k coordinates corresponding to the matrices, gives a new row of \(\tau _k(v).\) Therefore, the code \(B_k(v)\) is a quasi-G-code of length nk and index k. \(\square\)

Consider a quasi-G-code of index k. Then rearranging the coordinates so that the i-th coordinates of each group of k coordinates are placed sequentially, then it is easy to see that any \((g_1,g_2,\dots ,g_n) \in G^n\) holds the code invariant. Namely, any quasi-G-code of length kn and index k is a \(G^k\)-code. This gives the following.

Theorem 3.6

Let R be a finite Frobenius ring and let G be a finite group with \(v \in M_k(R)\). Then \(B_k(v)\) is a \(G^k\) code of length kn.

Proof

Follows from Lemma 3.5 and the previous discussion. \(\square\)

4 Generator matrices of the form \([I_{kn} | \tau _k(v)]\) and self-dual codes

In this section, we investigate constructions of self-dual codes from \(\tau _k(v)\) over the finite commutative Frobenius ring R.

Lemma 4.1

Let R be a finite commutative Frobenius ring. Also, let G be a group of order n and \(v=A_1g_1+A_2g_2+\dots +A_ng_n\) be an element of the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G.\) The matrix \([I_{kn}|\tau _k(v)]\) generates a self-dual code over R if and only if \(\tau _k(v)\tau _k(v)^T=-I_{kn}\).

Proof

Follows from the standard proof that \((I_m \ | \ A)\) generates a self-dual code of length 2m if and only if \(AA^T= - I_m\). \(\square\)

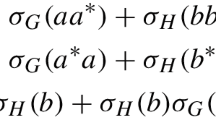

Recall that the canonical involution \(* : RG \rightarrow RG\) on a group ring RG is given by \(v^*=\sum _g a_g g^{-1},\) for \(v=\sum _g a_g g \in RG.\) Also, recall that there is a connection between \(v^*\) and v when we take their images under the map \(\sigma ,\) given by

The above connection can be extended to the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G.\) Namely, let \(* : M_k(R)G\rightarrow M_k(R)G\) be the canonical involution on the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G\) given by \(v^*=\sum _g A_gg^{-1},\) for \(v=\sum _g A_gg \in M_k(R)G\) where \(A_g\) are the \(k \times k\) blocks. Then we have the following connection between \(v^*\) and v under the map \(\tau _k\):

Lemma 4.2

Let R be a finite commutative ring. Let G be a group of order n with a fixed listing of its elements. Then the map \(\tau _k : v \rightarrow M(R)_{kn}\) is a ring homomorphism.

Proof

The proof is similar to the proof in Theorem 2.1 and simply consists of showing that addition and multiplication are preserved. \(\square\)

Now, combining together Lemmas 4.1, 4.2 and the fact that \(\tau _k(v)=-I_{kn}\) if and only if \(v=-I_k,\) we get the following corollary.

Corollary 4.3

Let \(M_k(R)G\) be a group matrix ring, where \(M_k(R)\) is a non-commutative Frobenius matrix ring. For \(v \in M_k(R)G,\) the matrix \([I_{kn}|\tau _k(v)]\) generates a self-dual code over R if and only if \(vv^*=-I_k.\) In particular v has to be a unit.

When we restrict our attention to a matrix ring of characteristic 2, we have that \(-I_k=I_k,\) which leads to the following further corollary:

Corollary 4.4

Let \(M_k(R)G\) be a group matrix ring, where \(M_k(R)\) is a non-commutative Frobenius matrix ring of characteristic 2. Then the matrix \([I_{kn}|\tau _k(v)]\) generates a self-dual code over R if and only if v satisfies \(vv^*=I_k,\) namely v is a unitary unit in \(M_k(R)G.\)

4.1 New binary self-dual codes of length 72

In this section, we search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12] by considering generator matrices of the form \([I_{kn} | \tau _{kn}(v)],\) where \(v \in M_k({\mathbb {F}}_2)G\) for different values of k and different groups G to show the strength of our construction and particularly, the strength of the matrix \(\tau _{kn}(v).\)

The possible weight enumerators for a Type I [72, 36, 12] codes are as follows ( [7]):

where \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) are parameters. The possible weight enumerators for Type II [72, 36, 12] codes are ( [7]):

where \(\alpha\) is a parameter.

Many codes for different values of \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) have been constructed in [2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16,17,18,19]. For an up-to-date list of all known Type I and Type II binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12] please see [13].

We now split the remaining of this section into subsections, where in each we consider a generator matrix of the form \([I_{kn} | \tau _k(v)]\) for a specific group G and some specific \(k \times k\) block matrices to search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12]. All the upcoming computational results were obtained by performing searches using a particular algorithm technique (see [14] for details) in the software package MAGMA ([1]).

4.1.1 The group \(C_2\) and \(18 \times 18\) block matrices

In this section, we consider the cyclic group \(C_2\) with some \(18 \times 18\) block matrices. Let \(G=\langle x \ | \ x^2=1 \rangle \cong C_{2}.\) Let \(v=\sum _{i=0}^1 Y_ix^i \in (M({\mathbb {F}}_2))_{18}C_{2},\) then

where

with

where \(A_i\) are some matrices. We now employ a generator matrix of the form \([I \ | \ \tau _{18}(v)],\) where I is the \(36 \times 36\) identity matrix, for different forms of the matrices \(A_i\) to search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12]. We only list codes with parameters in their weight distributions that were not known in the literature before. Also, since the matrix \(\sigma _{18}(v)\) is fully defined by the first row, we only list the first row of the matrices \(Y_0,\) and \(Y_1\) which we label as \(r_{Y_0}\) and \(r_{Y_1}\) respectively.

-

Case 1.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_1=revcirc(a_1,a_2,a_3),\\ A_2=revcirc(a_4,a_5,a_6),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{12}=revcirc(a_{34},a_{35},a_{36}). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

-

Case 2.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_1=revcirc(a_1,a_2,a_3),\\ A_2=revcirc(a_4,a_5,a_6),\\ \dots ,\\ A_6=revcirc(a_{16},a_{17},a_{18}),\\ A_7=circ(a_{19},a_{20},a_{21}),\\ A_8=circ(a_{22},a_{23},a_{24}),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{12}=circ(a_{34},a_{35},a_{36}). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

We summarise the results in Tables 3 and 4.

-

Case 3.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_1=circ(a_1,a_2,a_3),\\ A_2=circ(a_4,a_5,a_6),\\ \dots ,\\ A_6=circ(a_{16},a_{17},a_{18}),\\ A_7=revcirc(a_{19},a_{20},a_{21}),\\ A_8=revcirc(a_{22},a_{23},a_{24}),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{12}=revcirc(a_{34},a_{35},a_{36}).\\ \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

4.1.2 The group \(D_{18}\) and \(2 \times 2\) block matrices

In this section, we consider the dihedral group \(D_{18}\) with some \(2 \times 2\) block matrices.

Let \(G=\langle x,y \ | \ x^9=y^2=1, x^y=x^{-1} \rangle \cong D_{18}.\) Let \(v=\sum _{i=0}^8 \sum _{j=0}^1 A_{1+i+9j}x^iy^j \in M({\mathbb {F}}_2)D_{18},\) then

with

where \(A_i\) are some matrices.

We now employ a generator matrix of the form \([I | \tau _2(v)],\) where I is the \(36 \times 36\) identity matrix, for different forms of the matrices \(A_i\) to search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12]. We only list codes with parameters in their weight distributions that were not known in the literature before.

-

Case 1.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_1=circ(a_1,a_2),\\ A_2=circ(a_3,a_4),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{12}=circ(a_{35},a_{36}).\\ \end{array} \end{aligned}$$Since \(\tau _2(v)\) is fully defined by the first row, we only list the first rows of the matrices A and B which we label as \(r_A\) and \(r_B\) respectively. We summarise the results in Table 7.

-

Case 2.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} A_1= & {} \begin{pmatrix} a_1&{}a_2\\ a_3&{}a_1 \end{pmatrix}, A_2=\begin{pmatrix} a_4&{}a_5\\ a_6&{}a_4 \end{pmatrix}, A_3=\begin{pmatrix} a_7&{}a_8\\ a_9&{}a_7 \end{pmatrix}, \dots , A_9=\begin{pmatrix} a_{25},a_{26}\\ a_{27},a_{25} \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned}$$and

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_{10}=circ(a_{28},a_{29}),\\ A_{11}=circ(a_{30},a_{31}),\\ A_{12}=circ(a_{32},a_{33}),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{18}=circ(a_{44},a_{45}). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$We note here, that the first nine blocks are the \(2 \times 2\) per-symmetric matrices - defined by three independent variables and that the next nine blocks are the \(2 \times 2\) circulant matrices - defined by two independent variables both appearing in the first rows. This gives a search field of \(2^{45}\). To save space, we only list the three variables of each persymmetric matrix which we label as \(r_{A_1}, r_{A_2}, r_{A_3}, \dots , r_{A_9}\) and the first row of the matrix B which we label as \(r_B\) since this matrix is fully defined by the first row. We summarise the results in Table 8.

We note that the code \(C_{17}\) in the above table is the first example of a self-dual [72, 36, 12] code with \(\gamma =27\) in its weight distribution.

4.1.3 The group \(C_{6,3}\) and \(2 \times 2\) block matrices

In this section, we consider the cyclic group \(C_{6,3}\) and some \(2 \times 2\) matrices.

Let \(G=\langle x \ | \ x^{6 \cdot 3}=1 \rangle \cong C_{6,3}.\) Let \(v=\sum _{i=0}^5 \sum _{j=0}^2 A_{1+i+6j}x^{3i+j} \in M({\mathbb {F}}_2)C_{6,3},\) then

where

and where \(A_i\) are some \(2 \times 2\) matrices.

We now employ a generator matrix of the form \([I | \tau _2(v)],\) where I is the \(36 \times 36\) identity matrix, for different forms of the matrices \(A_i\) to search for binary self-dual codes with parameters [72, 36, 12]. We only list codes with parameters in their weight distributions that were not known in the literature before.

-

Case 1.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_1=circ(a_1,a_2),\\ A_2=circ(a_3,a_4),\\ A_3=circ(a_5,a_6),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{18}=circ(a_{35},a_{36}). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$We note that the search field here is \(2^{36}.\) Since the matrix \(\tau _2(v)\) is fully defined by the first row, we only list the first rows of the matrices A, B and C which we label as \(r_A, r_B\) and \(r_C\) respectively. We summarise the results in Table 9.

-

Case 2.

Here we let

$$\begin{aligned} A_1=\begin{pmatrix} a_1&{}a_2\\ a_3&{}a_1 \end{pmatrix}, A_2=\begin{pmatrix} a_4&{}a_5\\ a_6&{}a_4 \end{pmatrix}, A_3=\begin{pmatrix} a_7&{}a_8\\ a_9&{}a_7 \end{pmatrix}, \dots , A_9=\begin{pmatrix} a_{25},a_{26}\\ a_{27},a_{25} \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned}$$and

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{c} A_{10}=circ(a_{28},a_{29}),\\ A_{11}=circ(a_{30},a_{31}),\\ A_{12}=circ(a_{32},a_{33}),\\ \dots ,\\ A_{18}=circ(a_{44},a_{45}).\\ \end{array} \end{aligned}$$We note here, that the first nine blocks are the \(2 \times 2\) per-symmetric matrices - defined by three independent variables and that the next nine blocks are the \(2 \times 2\) circulant matrices - defined by two independent variables both appearing in the first rows. This gives a search field of \(2^{45}\). To save space, we only list the three variables of each persymmetric matrix which we label as \(r_{A_1}, r_{A_2}, r_{A_3}, \dots , r_{A_9}\) and the first rows of the matrices \(A_{10}, A_{11}, A_{12}, \dots , A_{18}\) which we label as \(r_{A_{10}}, r_{A_{11}}, r_{A_{12}}, \dots , r_{A_{18}}\) since these matrices are each defined by the first row. We summarise the results in Table 10.

We would like to stress that the above constructions represent a very small fraction of the possible matrix constructions that can be derived for the generator matrix \([I_{kn}|\tau _k(v)].\) That is, there are many more different choices for the groups and their sizes, the forms of the \(k \times k\) matrices and their sizes which can all lead to constructing optimal binary self-dual codes of various lengths - this shows the strength of our generator matrix.

5 Conclusion

In this work, we defined group matrix ring codes that are left ideals in the group matrix ring \(M_k(R)G.\) We generalized a well known matrix construction so that this generalization can be used to generate codes in two different ambient spaces. We presented a generator matrix for self-dual codes which we believe can be used to construct many new codes that could not be obtained from other, known in the literature, generator matrices. Additionally, we employed our generator matrix to search for binary self-dual codes. In particular, we constructed Type I binary [72, 36, 12] self-dual codes with new weight enumerators in \(W_{72,1}\):

and Type II binary [72, 36, 12] self-dual codes with new weight enumerators:

A suggestion for future work is to consider the generator matrix we presented in this work, for different groups, different types of the \(k \times k\) matrices and different alphabets to search for new optimal binary self-dual codes of different lengths.

References

Bosma, W., Cannon, J., Playoust, C.: The Magma algebra system. I. The user language. J. Symb. Comput. 24, 235–265 (1997)

Bouyukliev, I., Fack, V., Winna, J.: Hadamard matrices of order 36. In: European Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Applications, pp. 93–98 (2005)

Dontcheva, R.: New binary self-dual \([70,35,12]\) and binary \([72,36,12]\) self-dual doubly-even codes. Serdica Math. J. 27, 287–302 (2002)

Dougherty, S.T.: Algebraic Coding Theory Over Finite Commutative Rings. Springer Briefs in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, Berlin (2017). (ISBN 978-3-319-59805-5)

Dougherty, S.T., Leroy, A.: Self-dual codes over non-commutative Frobenius rings. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 27(3), 185–203 (2016)

Dougherty, S.T., Gildea, J., Taylor, R., Tylshchak, A.: Group rings, G-codes and constructions of self-dual and formally self-dual codes. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 86(9), 2115–2138 (2018)

Dougherty, S.T., Gulliver, T.A., Harada, M.: Extremal binary self dual codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 43(6), 2036–2047 (1997)

Dougherty, S.T., Kim, J.-L., Sole, P.: Double circulant codes from two class association schemes. Adv. Math. Commun. 1(1), 45–64 (2007)

Gulliver, T.A., Harada, M.: On double circulant doubly-even self-dual \([72,36,12]\) codes and their neighbors. Austalas. J. Comb. 40, 137–144 (2008)

Gurel, M., Yankov, N.: Self-dual codes with an automorphism of order 17. Math. Commun. 21(1), 97–101 (2016)

Hurley, T.: Group rings and rings of matrices. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 31(3), 319–335 (2006)

Kaya, A., Yildiz, B., Siap, I.: New extremal binary self-dual codes of length 68 from quadratic residue codes over \({\mathbb{F}}_2+u{\mathbb{F}}_2+u^2{\mathbb{F}}_2\). Finite Fields Their Appl. 29, 160–177 (2014)

Korban, A.: All known Type I and Type II \([72,36,12]\) binary self-dual codes, available online at https://sites.google.com/view/adriankorban/binary-self-dual-codes

Korban, A., Sahinkaya, S., Ustun, D.: A novel genetic search scheme based on nature—inspired evolutionary algorithms for self-dual codes. arXiv:2012.12248

Rains, E.M.: Shadow bounds for self-dual codes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 44, 134–139 (1998)

Tufekci, N., Yildiz, B.: On codes over \(R_{k, m}\) and constructions for new binary self-dual codes. Math. Slovaca 66(6), 1511–1526 (2016)

Yankov, N., Lee, M.H., Gurel, M., Ivanova, M.: Self-dual codes with an automorphism of order 11. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 61, 1188–1193 (2015)

Zhdanov, A.: New self-dual codes of length 72. arXiv:1705.05779

Zhdanov, A.: Convolutional encoding of 60, 64, 68, 72-bit self-dual codes. arXiv:1702.05153

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dougherty, S.T., Korban, A., Şahinkaya, S. et al. Group matrix ring codes and constructions of self-dual codes. AAECC 34, 279–299 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00200-021-00504-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00200-021-00504-9