Abstract

There is no formally defined terminology for the related entities transient osteoporosis of the hip (TOH), localized or regional migratory osteoporosis (RMO) and bone marrow edema syndrome (BMES). This study aimed to map the diversity and frequency of diagnostic terms and vocabulary utilized in the literature. A comprehensive search of electronic databases and reference lists was conducted. Publications that reported on patients with TOH, RMO, BMES, or related variants were eligible for inclusion. The terminologies were categorized based on the wording of the titles, abstracts, or texts. We included 561 publications, of which 423 were case reports, involving 2921 patients. Overall, TOH was the most commonly used term, occurring in 257 (45.8%). RMO was used in 34 (6.1%) and BMES in 57 (10.2%). The remaining used various combinations of transient, migratory, and regional in conjunction with either osteoporosis or bone marrow edema. Localized osteoporosis was not used. We identified three different terms related to pregnancy. In 76.3% of the publications, the terminology was related to osteoporosis and in 18.2% to bone marrow edema, although terminology did not correspond to actual findings. Bone marrow edema occurred as often as osteoporosis, and osteoporosis was generally ascertained by visual inspection of radiographs, seldom by bone densitometry. Many publications used osteoporosis-related terms without evidence that osteoporosis had been detected. The terminology of these closely related entities is confusing and unstandardized. The lack of formal definitions impedes accurate diagnosis, research on disease mechanisms, and effective treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rational discussions on epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes require the use of standardized and well-defined terminology. Without a common set of definitions, clear and effective communication between healthcare professionals, researchers, and patients is not possible. The disadvantages of not having a standardized vocabulary can be seen in the closely related conditions transient, migratory, or localized osteoporosis, as well as bone marrow edema syndrome (BMES). These terms are all used for patients with spontaneous pain in a lower extremity joint, accompanied by local bone marrow edema and/or osteoporosis. It is unclear whether they refer to discrete, clinically meaningful concepts, or different manifestations of the same underlying pathology.

The origins of these designations date back several decades, with each term being introduced to describe specific clinical presentations. Transient osteoporosis of the hip (TOH) was first used in 1959 about 3 pregnant women with spontaneous, debilitating hip pain, and radiographic demineralization of the femoral heads and acetabulum [1]. Although the pain eventually subsided, and the X-rays returned to normal over several months; one woman was found to have an impacted subcapital fracture. A similar clinical picture, but without fractures, was later described in 10 adult males [2]. Further observations revealed that spontaneous pain and demineralization could also occur in the knees and ankles, with subsequent episodes in other joints, leading to the introduction of a new term, regional migratory osteoporosis (RMO) [3,4,5]. The advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allowed for the detection of bone marrow edema in the affected joints, giving rise to yet another term; bone marrow edema syndrome (BMES) [6, 7]. Bone marrow edema is a non-specific lesion commonly seen in inflammatory, traumatic, neoplastic, and degenerative conditions, characterized by low to intermediate fluid signal on T1-weighted, and high signal on T2-weighted imaging [8]. Similar to transient osteoporosis and RMO, BMES has been observed in various joints in the lower extremities such as hips, knees, ankles, and feet. In 1990, the International Classification of Diseases incorporated the code M81.6–Localized Osteoporosis [Lequesne] (LO) into the ICD-10 [9], named after the author who first proposed the term TOH [2]. It is uncertain whether this terminology has been widely adopted by the medical community.

Despite their usage, none of these terms have been formally defined, and there are no diagnostic or classification criteria. The lack of standardized terminology and clear definitions has led to confusion when referring to patients with symptoms and findings associated with these conditions. As a result, additional terms and variants have emerged, further complicating the literature, impeding access to relevant information and hindering research efforts. Moreover, the rarity of these conditions makes it challenging to access sufficient patient data for comprehensive research.

This study is part of a larger project aiming to enhance the understanding of these conditions through a critical review of the existing literature [10]. The specific objective of this scoping review is to explore the diversity and frequency of diagnostic terms and vocabulary utilized in publications related to patients diagnosed with TOH, RMO, BMES, LO, and similar conditions. By addressing the need for standardized terminology and examining the existing terminology landscape, this study aims to contribute to improved communication, research comparability, and better patient care.

Methods

The reporting of this review was guided by the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews checklist [11].

Protocol and registration

The study protocol was registered in Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VR56C).

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were formulated after the SPIDER search tool [12]. We included publications (journal articles and conference abstracts) of patients with TOH, RMO, BMES, LO, or variants of these entities. If a relevant article was unavailable in full text, we used the journal abstract. No restrictions were applied regarding study design, sample size, language, country of origin, or date of publication. Publications not involving patients such as opinion papers, reviews, and policy documents were not eligible. Nor were publications that included patients with relevant diagnoses but where data from these patients could not be independently extracted.

Information sources

We searched the Embase and MEDLINE databases on the Ovid platform (Wolters Kluwer, New York City, NY) from inception to 16 February 2023. In order to complement this search and to identify other potentially relevant terms, we manually checked the reference lists of review articles found at title and abstract screening, and we used EndNote in combination with the Web of Science and Scopus databases to semi-automatically search the reference lists of the included publications [13].

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [14]. A rudimentary round of searches for TOH, RMO and BMES was done to identify relevant MeSH terms as well as different variations of the terms relating to the terminology. Different Boolean operators were tested to minimize the number of false hits. The final search strategy developed was as follows:

-

1.

osteoporosis/ or bone demineralization, pathologic/

-

2.

(osteoporos* or demineral*).tw.

-

3.

1 or 2

-

4.

(transient or transitory or localized or reversible).tw.

-

5.

(osteoporosis/ or bone demineralization, pathologic/ or (osteoporos* or demineral*).tw.) adj10 (transient or transitory or localized or reversible).tw.

-

6.

remove duplicates from 5

-

7.

(“regional” or “migrat*”).tw.

-

8.

(osteoporosis/ or bone demineralization, pathologic/ or (osteoporos* or demineral*).tw.) adj10 (“regional” or “migrat*”).tw.

-

9.

remove duplicates from 8

-

10.

(Edema/ or Oedema/) and Bone Marrow/

-

11.

(“bone marrow edema” or “bone marrow oedema”).tw.

-

12.

10 or 11

-

13.

(syndrom* or shifting or transient or transitory or localized).tw.

-

14.

(((Edema/ or Oedema/) and Bone Marrow/) or (“bone marrow edema” or “bone marrow oedema”).tw.) adj6 (syndrom* or shifting or transient or transitory or localized).tw.

-

15.

remove duplicates from 14

-

16.

6 or 9 or 15

-

17.

remove duplicates from 16

Selection of sources of evidence

Identified records were imported into EndNote (Clarivate, USA) and transferred to Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia). After removal of duplicates, references were checked for retractions using the Retraction Watch Database (The Center for Scientific Integrity, NY) integrated in Zotero (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, USA).

Selection process

Prior to the start of the selection process, three investigators screened the same 15 publications, discussed the results, and amended the screening and data extraction manual. The retrieved publications were then manually screened by two independent investigators. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or decided by the third investigator.

Data extraction

Each publication was independently reviewed by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or decided by a third reviewer. When necessary, text was translated using Google translate [15], and optical character recognition was performed.

We extracted publication type (journal article, journal abstract or conference abstract), year, country of origin, and study design (case report [≤ 3 patients]; case series [≥ 4 patients]; cohort study; controlled trial; non-controlled trial), the number of patients included in each publication, imaging modalities used, assessments of bone marrow edema and assessments of osteoporosis, including bone densitometry, and fractures. For cohort studies and trials, we extracted the eligibility criteria used for the inclusion of patients.

We categorized the terminologies according to the wording of the publication titles. Publications were categorized as TOH if the title included transient osteoporosis of the hip, as RMO if it included regional migratory osteoporosis, and as BMES if it included bone marrow edema syndrome. If none of these were applicable, or the wording was ambiguous, the publication was categorized as other. In case of a non-English title, the Embase and MEDLINE indexed English version was used if provided, the full text was examined for an author-translated version, or the original title was translated. If no term was found in the titles, we examined the abstracts or texts.

We did not address study quality [11].

Synthesis of results

Geographic origins

The geographical origins of the publications were tabulated according to subregions in the United Nations M49 standard [16] and presented by country on a choropleth map.

Refinement and categorization of terminologies

The publications initially categorized with other terminologies were reexamined and coded according to their terminology characteristics. This process involved a collaborative process between two reviewers who examined the titles, and if necessary, the abstracts or full texts.

Analysis of terminology in regard to osteoporosis and bone marrow edema

To gain a better understanding of the authors’ choices of terminology regarding osteoporosis and bone marrow edema, we initially sorted the publications into three primary groups based on whether they utilized (i) osteoporosis-related terms, (ii) bone marrow edema-related terms, or (iii) miscellaneous terms. Publications that contained terminology that was linked to both osteoporosis and bone marrow edema, or was not related to either, were classified in the miscellaneous terms category. Subsequently, we scrutinized the reported clinical discoveries of osteoporosis and bone marrow edema in each of these three main groups. We regarded findings reported as osteoporosis, osteopenia, demineralization, or decalcification, or a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of ≤ -2.5 as evidence for osteoporosis [17]. If T-scores were assessed at multiple skeletal sites, we recorded the outcome with the lowest T-score. We only accepted findings from MRI scans as evidence for bone marrow edema. Assuming that publications with individual data reflected more precise information regarding osteoporosis and bone marrow edema findings, we conducted two separate analyses, one on case reports and a second on case series, cohort studies, and trials collectively. We also analyzed terminology in regard to study design and to eligibility criteria (in cohort studies and trials only).

Software

The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY), the R programming language v. 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and RStudio software environment v. 2023.3.1.446 (Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA), the packages tidyverse v. 2.0.0 [18], countrycode v. 1.4.0 [19], sf v. 1.0–13 [20], and tmap v. 3.3.3 [21].

Results

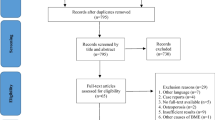

Selection of sources of evidence

We identified a total of 3626 records through database searches. After removing duplicates, we screened 3511 records, of which 701 full-text documents were reviewed. Subsequently, we included a total of 475 publications. An additional 86 studies were identified through reference list checks, resulting in a total of 561 included studies. Refer to Fig. 1 for the flow chart.

Publication characteristics

Table 1 displays the study design and publication type of the included publications. The majority of the publications were comprised of case reports (n = 423) or case series (n = 122).

The geographical origins of the included publications are presented in Table 2. A majority originated in Southern Europe, particularly in the Mediterranean countries Spain (n = 49), Italy (n = 44), Turkey (n = 44), and Greece (n = 23), but most regions of the world were represented, see Fig. 2. The total number of patients reported by the publications was 2921.

Terminologies

TOH was the most commonly used unique term, occurring in 257 (45.8%) of the 561 included publications (Table 3). RMO was used in 34 (6.1%) and BMES in 57 (10.2%) publications. Localized osteoporosis was included in a more extensive phrase in one publication [22], but was otherwise not used. Examples of miscellaneous terms were migratory osteolysis [23] and hip algodystrophy [24]. Various combinations of transient (or transitory), migratory and regional were common, both in conjunction with osteoporosis and with bone marrow edema, such as recurrent migratory transient bone marrow edema [25] or transient osteoporosis of the hip/bone marrow edema syndrome [26]. Other recurring adjectives were reversible, shifting, idiopathic, and painful. We found three pregnancy related terms; transient osteoporosis of pregnancy (n = 36), pregnancy-associated osteoporosis (n = 8), and pregnancy-associated transient osteoporosis of the hip (n = 3).

Terminology in regard to osteoporosis and bone marrow edema

Overall, 428 (76.3%) publications used terms that were related to osteoporosis, 102 (18.2%) used terms that were related to bone marrow edema, and 31 (5.5%) used miscellaneous terms. Figure 3 shows the development in the use of the three main categories from 1959 to 2022.

Terminology used according to reported findings of osteoporosis and bone marrow edema is shown in Table 4.

Terminology utilized in case reports

Out of the 423 case reports analyzed, 260 (61.5%) reported osteoporosis findings. Among these reports, the majority (144/260) relied solely on conventional radiography for assessment, while 111 utilized densitometry (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, DXA (n = 95), single or dual photon absorptiometry (n = 4), quantitative computed tomography (n = 3), quantitative ultrasound (n = 1), multiple modalities (n = 3), unspecified (n = 5)). Fifty publications reported T-scores using DXA.

Of the 79 case reports describing clinical fractures, the majority (n = 68, 86.1%) occurred during pregnancy or the puerperium. Terminology related to osteoporosis was prevalent in these reports, with 69 using osteoporosis-related terms, while 3 used bone marrow edema-related terms and 7 employed other terms.

Of all case reports, 302 (71.4%) reported bone marrow edema findings. Notably, among the case reports utilizing osteoporosis-related terms, the incidence of bone marrow edema findings was as frequent as osteoporosis findings (69.2% and 63.8%, respectively) (refer to Table 4). Conversely, in the case reports utilizing bone marrow edema-related terms, the presence of bone marrow edema was reported in 100%, while osteoporosis was observed in 43.1%.

One hundred sixty-six case reports reported findings of both osteoporosis and bone marrow edema. Among these reports, 143 (86.1%) utilized osteoporosis-related terminology, while 22 (13.3%) employed bone marrow edema-related terms. A single report (0.6%) utilized alternative terminology. Furthermore, of 136 case reports with findings of bone marrow edema, but no mentioning of findings of osteoporosis, 102 (75%) utilized osteoporosis-related terms, while 29 (21.3%) employed bone marrow-related terms.

Terminology used in case series, cohort studies and trials

In case series, cohort studies, and trials, the distribution of findings based on terminology used was comparable to that in the case reports (Table 4). Publications using terms related to osteoporosis had a somewhat higher rate of osteoporosis findings, while miscellaneous terms were slightly more common than in the case reports.

Terminology in relation to study design

The majority of case reports (354/423, 83.7%) used terms related to osteoporosis, while the majority of cohort studies and trials (12/16, 75%) used terms related to bone marrow edema (see Table 5).

Terminology in relation to eligibility criteria

Among the 16 cohort studies or trials, seven reported pre-specified eligibility criteria, all of which required the detection of bone marrow edema on MRI. One study additionally required “increased radiolucency on X-ray.” Six of the seven studies used terms related to bone marrow edema, and one used a term related to both osteoporosis and bone marrow edema. Of the nine cohort studies or trials without pre-specified eligibility criteria, all but one reported the presence of bone marrow edema, and four also reported the presence of osteoporosis. Six used bone marrow edema-related terms, and three used osteoporosis-related terms.

Discussion

This comprehensive literature review demonstrates that TOH was utilized in 46% of the 561 publications reviewed, while BMES and RMO were utilized in 10% and 6% of cases, respectively. The remaining publications used miscellaneous expressions containing various derivatives of these three original terms. A few older publications, predominantly in French, utilized the term algodystrophy. Algodystrophy has also been used as a term for Sudeck atrophy or reflex sympathetic dystrophy, which is now known as chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) [27]. Interestingly, none of the publications used the only relevant term included in the ICD-10, namely localized osteoporosis [Lequesne]. In the recently introduced ICD-11 [28], the coding for osteoporosis was modified, and this specific diagnosis was removed. It is also worth noting that in the ICD-10, Sudeck atrophy (M89.0) is listed as an exclusion criterion for Localized Osteoporosis [Lequesne].

The history and evolution of the original terms as well as those uncovered in this review indicate a very close relationship between them. There may be some exceptions, such as those linked to pregnancy and the puerperium. However, the nomenclature of pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis (PLO) is also unclear. In the literature, the term PLO is commonly reserved for cases presenting with vertebral fractures [29,30,31]. Almost all of the fractures reported in this review occurred in the proximal femur. Kovacs and Ralston [31] argued that TOH and PLO are two separate conditions, considering TOH to be a focal disorder, not a manifestation of altered calciotropic hormone levels or systemic bone resorption during pregnancy. Our findings do not support this view. The fractures identified in this review overwhelmingly occurred in pregnant or lactating women. A hip fracture in a young mother is a serious complication. This highlights the importance of using precise and consistent terminology, facilitating the development of personalized risk prediction and prevention strategies. Furthermore, the occurrence of fractures in patients labeled with transient osteoporosis contradicts the common perception of transient osteoporosis as a painful but self-limiting condition. It is worth noting that in the ICD-10, localized osteoporosis [Lequesne] is classified as a subclassification under the heading M81 Osteoporosis without pathological fracture.

Nearly all terms identified in this review were related to either osteoporosis or bone marrow edema. The prevalent use of TOH likely reflects that the hip is the most frequently affected joint, but also that TOH was the first term that was introduced and is the best-known. Perhaps the most striking finding from our review is that osteoporosis-related terms were commonly used even when there was no evidence that osteoporosis had actually been detected. This suggests that the choice of terminology largely relies on historical conventions. Despite numerous publications reporting findings of bone marrow edema, few utilized bone marrow edema-related terminology. Also, in publications that reported the detection of both osteoporosis and bone marrow edema, the authors generally chose osteoporosis-related terms. This is surprising since most studies ascertained osteoporosis via subjective interpretation of demineralization on radiographs, a method known to be insensitive and unreliable [32]. Few performed bone densitometry, and even fewer reported results using T-scores, which the operational definition of osteoporosis is based on [17]. A challenge with measuring BMD in this patient group is that routine use of the recognised reference method, namely DXA, is limited to the lumbar spine and proximal femur, and hence inapplicable to patients with symptoms in the knees, ankles, or feet. In contrast, bone marrow edema was usually visible on MRI at presentation [7, 33, 34]. We found no evidence of a shift towards BMES-related terminology following the introduction of MRI and the identification of bone marrow oedema.

With the exception of one publication, all included patients experienced spontaneous joint pain in their lower extremities. Many authors argue that the various terms used to describe this condition denote a shared pathological process [22, 26, 35,36,37,38,39]. We believe it is prudent to establish a common diagnostic category that encompasses all patients exhibiting this clinical presentation due to the strong association observed between these conditions. Because of the difficulty in detecting reduced bone mineral density outside of the hip and the common perception of osteoporosis as a painless condition, we believe that such a category should not be associated with osteoporosis. Joint pain is the characteristic feature of these conditions. A linkage to bone marrow edema, such as BMES, would be more appropriate based on the majority of cohort studies and trials that employed bone marrow edema-related terminology and used it as an inclusion criterion in prospective studies. Eligibility criteria for prospective studies would arguably be the result of careful consideration by experts in the field. Patel [38] suggested primary BMES to avoid confusion with the numerous other diseases associated with juxta-articular bone marrow edema. Speculations that BMES may be a precursor to osteonecrosis have not been confirmed; now, those conditions are considered to be separate [40,41,42]. We do not agree with Hayes [43] who suggested that BMES should be reserved only for patients who do not develop radiographically evident osteopenia. However, neither ICD-10 nor ICD-11 include codes applicable to bone marrow edema-related terms. A logical subsequent step would be to define criteria for this common category, which could be employed to diagnose individual patients or to create homogenous cohorts for clinical research. Thorough phenotypical characterization is a prerequisite for the development of such criteria [44].

This review shows that these conditions occur worldwide with a notable portion originating in the Mediterranean countries. We cannot say whether this reflects increased incidence in these countries or is a result of reporting bias. To our knowledge, no epidemiological studies have been performed.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this review is the large number of publications included, the use of a preregistered protocol, and a transparent and reproducible methodology according to guidelines for conducting scoping reviews [11, 45, 46]. Additionally, we used a peer review literature search strategy. To complement the electronic search, we performed a thorough search of reference lists. This did not identify entirely new terms or designations different from those included in the initial search.

There are several limitations to this study. The sensitivity of the search strategy, and therefore the comprehensiveness of the sample, is uncertain. Searching reference lists after completing the electronic search increased the number of included publications by approximately one-fifth. Compared with the publications identified electronically, those found via reference lists were typically older and in national languages, and lacked key words or abstracts. The same was the case with a few records that, during screening, were considered potentially relevant but which we were unable to retrieve. As suggested for scoping reviews, we did not address study quality, but acknowledge that the included publications likely had uneven quality. Many were published in journals with no information regarding a peer review process, and some were conference proceedings. We excluded review articles, editorials, commentaries, etc., and may have missed experts’ opinions and views regarding terminology. Relevant publications that utilized solely non-English terms may have been omitted. To overcome language barriers, we translated titles, abstracts, or text using Google Translate, and cannot rule out that some terms were misinterpreted due to linguistic issues. Furthermore, our categorization of terminologies involved a certain degree of subjective judgment.

The vast majority of the publications included in this study were case reports, which typically provide information about rare diseases or unfamiliar presentations. The limited number of cohort studies or trials underscores the lack of systematic research in this area. In the absence of high-quality research, case reports can expand our knowledge base [47, 48]. In some of the publications that reported aggregate data, information regarding imaging findings of osteoporosis was either incomplete or nonexistent. We scored each publication, not individual patients, and thus the results obtained from the case reports will be more precise than those obtained from the case series, cohort studies, and trials.

Clear and operational entities are prerequisites for medical research. Descriptions must precede understanding [47]. Therefore, this review provides a basis for further work towards a more uniform terminology of these entities.

Conclusion

The review underscores an urgent necessity to clarify the validity of the diagnostic terms related to transient or migratory osteoporosis and bone marrow edema syndrome. Ambiguous terminology and the absence of distinct definitions hinder accurate diagnosis, as well as research on the disease mechanisms, prognosis, and effective treatment. We suggest the establishment of a common overarching term that incorporates the various terminologies that have been employed until now. This overarching term should be linked to bone marrow edema, rather than osteoporosis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Curtiss PH Jr, Kincaid WE (1959) Transitory demineralization of the hip in pregnancy. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 41-A:1327–33

Lequesne M (1968) Transient osteoporosis of the hip. A nontraumatic variety of Sudeck’s atrophy. Ann Rheum Dis 27(5):463–71

Duncan H (1969) Regional migratory osteoporosis. South Med J 62:41–44

Hunder GG, Kelly PJ (1968) Roentgenologic transient osteoporosis of the hip: a clinical syndrome? Ann Intern Med 68(3):539–552

Gupta RC et al (1973) Regional migratory osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum: Off J Am Coll Rheumatol 16(3):363–368

Wilson AJ et al (1988) Transient osteoporosis: transient bone marrow edema? Radiology 167(3):757–760. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.167.3.3363136

Hofmann S et al (1993) Correlation of MRI and histomorphological findings in bone marrow oedema syndrome of the hip. Eur Radiol 3(5):408–412

Starr A et al (2008) Bone marrow edema: pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and imaging. Acta Radiol 49(7):771–786

World Health Organization (2008) International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2008/en#/M80-M85. Accessed 30 May 2023

Grøvle L, Hasvik E, Johansen M, Haugen AJ (2022) Protocol for a scoping review on transient osteoporosis, bone marrow edema syndrome and related conditions. https://osf.io/vr56c/. Accessed 25 May 2023

Tricco AC et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A (2012) Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 22(10):1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

Bramer WM (2018) Reference checking for systematic reviews using Endnote. J Med Lib Assoc: JMLA 106(4):542

McGowan J et al (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75:40–46

Jackson JL et al (2019) The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non–English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 171(9):677–679

United Nations Statistics Division. Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49). https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/. Accessed 09 Jun 2023

Kanis JA et al (2019) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 30(1):3–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5

Wickham H et al (2019) Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4(43):1686

Arel-Bundock V, Enevoldsen N, Yetman C (2018) countrycode: an R package to convert country names and country codes. J Open Source Softw 3(28):848

Pebesma EJ (2018) Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. R J 10(1):439

Tennekes M (2018) tmap: Thematic Maps in R. J Stat Softw 84:1–39

Ringe JD, Dorst A, Faber H (2005) Effective and rapid treatment of painful localized transient osteoporosis (bone marrow edema) with intravenous ibandronate. Osteoporos Int 16(12):2063–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-2001-6

Strashun A, Chayes Z (1979) Migratory osteolysis. J Nucl Med 20(2):129–132

Hamidou M et al (1990) Hip algodystrophy and pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 19(3):324–326

Alsaed O, Hammoudeh M (2018) Recurrent migratory transient bone marrow edema of the knees associated with low vitamin D and systemic low bone mineral density: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Rheumatol Print 2018:7657982. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7657982

Bin Abdulhak AA et al (2011) Transient osteoporosis of the hip/bone marrow edema syndrome with soft tissue involvement: a case report. Oman Med J 26(5):353–355. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2011.86

Doury P, Hoffmann S, Plenk H (1994) Bone-marrow oedema, transient osteoporosis, and algodystrophy [5]. J Bone Joint Surg - Ser B 76(6):993–994. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.76b6.7983140

World Health Organization (2022) International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-11). 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f2113001430. Accessed 29 May 2023

Hardcastle SA (2022) Pregnancy and lactation associated osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 110(5):531–545

Kyvernitakis I et al (2018) Subsequent fracture risk of women with pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis after a median of 6 years of follow-up. Osteoporos Int 29:135–142

Kovacs C, Ralston S (2015) Presentation and management of osteoporosis presenting in association with pregnancy or lactation. Osteoporos Int 26:2223–2241

Garton MJ et al (1994) Can radiologists detect osteopenia on plain radiographs? Clin Radiol 49(2):118–122

Grimm J et al (1991) MRI of transient osteoporosis of the hip. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 110(2):98–102

Bloem JL (1988) Transient osteoporosis of the hip: MR imaging. Radiology 167(3):753–755. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.167.3.3363135

Ververidis AN et al (2020) The efficacy and safety of bisphosphonates in patients with bone marrow edema syndrome/transient osteoporosis: a systematic literature review. J Orthop 22:592–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2020.11.011

Paraskevopoulos K et al (2023) Comparison of various treatment modalities for the management of bone marrow edema syndrome/transient osteoporosis in men and non-pregnant women: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 34(2):269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-022-06584-8

Asadipooya K, Graves L, Greene L (2017) Transient osteoporosis of the hip: review of the literature. Osteoporos Int 28:1805–1816

Patel S (2014) Primary bone marrow oedema syndromes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53(5):785–792. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket324

Uzun M et al (2013) Regional migratory osteoporosis and transient osteoporosis of the hip: are they all the same? Clin Rheumatol 32(6):919–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2243-1

Guerra JJ, Steinberg ME (1995) Distinguishing transient osteoporosis from avascular necrosis of the hip. JBJS 77(4):616–624

Koo KH, Kim TY (2007) Distinguishing transient bone marrow edema syndrome of the hip from femoral head osteonecrosis. Seminars Arthroplasty JSES 18(3):198–202. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sart.2007.06.006

Kim Y-M, Oh H, Kim H (2000) The pattern of bone marrow oedema on MRI in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg. 82(6):837–841 (British volume)

Hayes CW, Conway WF (1993) Daniel WW (1993) MR imaging of bone marrow edema pattern: transient osteoporosis, transient bone marrow edema syndrome, or osteonecrosis. Radiographics: Rev Publ Radiol Soc North Am Inc. 13(5):1001–1011 (discussion 1012)

Aggarwal R et al (2015) Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res 67(7):891

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Pollock D et al (2023) Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 21(3):520–532

Nissen T, Wynn R (2014) The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res Notes 7(1):1–7

Gagnier JJ et al (2013) The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Health Med 2(5):38–43

Funding

Open access funding provided by Østfold Hospital Trust No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grøvle, L., Haugen, A.J., Johansen, M. et al. The terminologies of transient, migratory, or localized osteoporosis, and bone marrow edema syndrome: a scoping review. Osteoporos Int 35, 217–226 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06929-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06929-x