Abstract

Summary

Patients hospitalised with vertebral fragility fractures were elderly, multimorbid and frail and lead to poor outcomes. Their hospital treatment needs to consider this alongside their acute fracture. A systematic organised model of care, such as an adaptation of orthogeriatric hip fracture care, will offer a more holistic approach potentially improving their outcomes.

Purpose

Patients admitted to hospital with vertebral fragility fractures are elderly and have complex care needs who may benefit from specialist multidisciplinary input. To date, their characteristics and outcomes have not been reported sufficiently. This study aims to justify such a service.

Methods

Patients admitted with an acute vertebral fragility fracture over 12 months were prospectively recruited from a university hospital in England. Data were collected soon after their admission, at discharge from hospital and 6 months after their hospital discharge on their characteristics, pain, physical functioning, and clinical outcomes.

Results

Data from 90 participants were analysed. They were mainly elderly (mean age 79.7 years), multimorbid (69% had ≥ 3 comorbid condition), frail (56% had a Clinical Frailty Scale score ≥ 5), cognitively impaired (54% had a MoCA score of < 23) and at high risk of falls (65% had fallen ≥ 2 in the previous year). Eighteen percent died at 6 months. At 6 months post-hospital discharge, 12% required a new care home admission, 37% still reported their pain to be severe and physical functioning was worse compared with their preadmission state.

Conclusion

Patients hospitalised with vertebral fragility fractures were elderly, multimorbid, frail and are susceptible to persistent pain and disability. Their treatment in hospital needs to consider this alongside their acute fracture. A systematic organised model of care, such as an adaptation of orthogeriatric hip fracture care, will offer a more holistic approach potentially improving their outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vertebral fracture is the most common osteoporotic fragility fracture—fractures that occur after minimal or no trauma [1, 2]. In the UK, an estimated 66,000 vertebral fractures occur annually, and an extra 18,000 cases are projected annually by 2025 [3]. Only 10–35% of people with vertebral fractures that require medical attention are admitted to hospital [4, 5]. Patients with vertebral fractures who are hospitalised have an average age of 81 years, and are likely to have complex diagnostic, therapeutic and care needs [6]. Hence, they may benefit from specialist input such as comprehensive geriatric assessment [7]. To date, the characteristics and outcomes post-hospitalisation of these patients have not yet been reported sufficiently to define the need for such specialist input [6]. The aim of this study was to describe characteristics and outcomes of patients with vertebral fractures admitted to hospital to justify and prepare for the development of specialist input for this group.

Methods

A single centre prospective cohort study was conducted in the Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham, UK, which serves a local population of 800,000 people [8] and hosts a major trauma centre serving a catchment area of over 4 million people. Participants were recruited prospectively for a period of 12 months from 3 October 2016 to 16 October 2017.

Patients were eligible for recruitment if they had presented with an acute vertebral fragility fracture of the thoracic or lumbar spine. An acute vertebral fragility fracture was defined as a fracture caused by a fall from a standing height or less, or due to sudden compressive loading on the spine (e.g. during lifting, bending forward, coughing or sneezing). Radiological confirmation using semi-quantitative methods on visual inspection of lateral spinal radiographs was required, and the clinical findings had to correlate with symptoms of acute or acute on chronic back pain. Images were single read. Exclusion criteria were the following: age < 50; high impact injury; presence of a concomitant fracture; known or suspected malignancy; patients transferred from another hospital; known primary bone disorder other than osteoporosis; and a terminal illness.

Patients hospitalised with either a confirmed or suspected vertebral fracture were invited to participate. The research team were notified of eligible potential participants by the patient’s treating clinical team. Participants were recruited by a single researcher (TO), a doctor trained in orthogeriatric medicine. The process for obtaining participant’s informed consent was in accordance within the provisions of the England and Wales Mental Capacity Act 2005 [9].

Participants had data collected on recruitment, at discharge from hospital and at 6 months after their hospital discharge. Baseline data comprised demographics, copathology, frailty status, cognition, mood, falls history, pain and physical functioning. Data were collected at discharge and at 6 months after discharge from hospital for pain, physical functioning and residential status. Six months after their discharge from hospital, data were also collected on mortality and quality of life. Data were gathered using a combination of either hospital health records, direct observation or what was reported by participant’s carers. Pain assessment at each of this time point was recorded using the numeric rating scale (NRS), an 11-point numeric rating scale at rest, mobilising and the reported average pain in the preceding 24 h [10]. Physical functioning was measured using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [11], Barthel Index (BI) [12], Elderly Mobility Scale (EMS) [13] and the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) [14]. Frailty was assessed with the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [15], cognition with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [16], mood with the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [17] and quality of life with the EQ-5D [18].

The sample size was determined by the time available to complete this research project, the estimated number of patients hospitalised and the precision of the results of the quantitative analysis conducted in this observational study. Using the local spinal surgical unit referral registry, it was estimated that there would be 100 patients potentially recruited into the study over 12 months. Assuming an attrition rate of 20%, which has been suggested as a threshold that becomes significant in clinical trials [19], at the end of the 6-month follow-up period for this observational study, sample size precision was inferred with a sample of 80 participants at follow-up for the estimation of pain was explored. The prevalence of moderate-severe pain at 6 months has been reported at 53% on the pain NRS [20]. If this prevalence of pain was seen in a sample of 80 participants, the 95% confidence intervals would be 42–63%, a precision of ± 10.5%. Increasing sample size to 120 by recruiting for 18 months would have a minimal effect, changing the precision to ± 9%. Hence, recruitment of 100 participants over 12 months was determined by the study team to be adequate to explore the study’s aim.

Participants were not included in the analysis if subsequent investigation identified an exclusion criterion. Patient characteristics and outcomes were reported using descriptive statistics. Analysis was performed on available data only. Pain was categorised according to its severity based on the NRS score (no pain-0, mild pain-1–3. moderate pain-4–6, severe pain-7–10) [10]. Changes in clinical outcomes were compared between those at 6 months, at discharge, with those on admission and prefracture level using parametric and nonparametric tests depending on distribution of the data. Univariate analysis was performed to examine the association between change in NRS, RMDQ, BI, EMS and NEADL and potential predictors of recovery as follows: age, number of comorbidities, frailty, cognitive impairment (MoCA cut-off of 23 points), depression (GDS ≥ 5) and having more than one vertebral fracture. Baseline characteristics of participants completing follow up at 6 months and those that did not were compared. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.

The study received ethical approval from the East of England—Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (REC 16/EE/0249). Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust was sponsor to this study. The study was registered with ISRCTN (reference 14436287).

Results

Over 12 months, 100 participants were recruited into the study within a median of 2 days (IQR 4 days) from their admission into hospital. Ten participants were withdrawn after further clinical information during their hospital admission excluded their eligibility (Fig. 1). Data were analysed on the remaining 90 participants presenting with 136 vertebral fractures affecting the thoracic and lumbar spine (Table 1). At the 6-month follow-up, participants that dropped out (declined or unable to contact, n = 10) were compared with those that did not for differences in age, frailty, pain severity, cognitive impairment, RMDQ and number of comorbidities.

Participants were elderly (mean age 79.7), largely (96%) community dwelling, but with substantial comorbidity (69% had at least 3 comorbidities). Over half were rated as frail (56%, CFS score of at least 5) and cognitively impaired (54% MoCA score less than 23) and at high risk of falls (65% having fallen twice or more in the previous year) (Table 1).

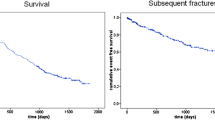

The median (IQR) acute hospital stay was 10 (16) days. Six of ninety participants (7%) died in hospital. All deaths were due to the following infections: four chest infections, one urine infection and one infection of uncertain source. Forty-five of ninety participants (50%) returned to their usual place of residence without any increase in their care support, Twenty-two of ninety (24%) returned to their usual residence with an increase in their care, 13/90 (14%) were transferred to a rehabilitation facility and 4/90 (4%) were transferred to a care home. By 6 months, further 7 participants had changed residence to a care home (11/90 participants, 12%), and further 10 participants had died (16/90 participants, 18%).

Pain on admission was worse during mobilisation. Pain on mobilisation on admission was rated as severe in the overwhelming majority (94%). Over time, pain levels decreased, but pain on mobilisation was still rated as severe in 37% of the participants at 6 months and only 19% reported no pain at all (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Participants on admission were largely disabled and immobile (Table 2). Improvements were seen over time, but even at 6 months, they were slightly more disabled, and mobility was worse compared with their pre-admission state (at 6-months vs pre-admission, BI, 15.8 vs 17.2, p < 0.01; NEADL scale, 11.6 vs 13.4, p < 0.01; EMS, 13.5 vs 15.6, p < 0.01). At 6 months, there was improvement with an average reduction in RMDQ of 9.0 points (95% CI − 10.8 to − 7.1). Mood and condition did not differ significantly between baseline and at 6-month follow-up. These findings were further supported by participant reported EQ-5D-3 L responses at 6 months, where 81% reported problems with their mobility, 48% problems with self-care, 65% problems performing their usual activities and 63% still had moderate to extreme pain (Table 3).

Change in NRS, RMDQ, EMS, BI and NEADL were not associated with age, number of comorbidities, frailty, cognitive impairment, depression and having more than one fracture, with one exception. There was a difference in change in NEADL between those with and without cognitive impairment. Participants with cognitive impairment had a mean (SD) decline of 4.6 (6.5) in their NEADL score compared with those without cognitive impairment of a decline by 1.8 (3.1), p = 0.04. Previous fractures had no change in NEADL.

Discussion

This study comprehensively described patients hospitalised with acute vertebral fragility fractures. Most patients were elderly, comorbid and many were frail and cognitively impaired. Over two-thirds presented to hospital 3 days after the onset of their symptoms. This suggests that patients may have been trying to manage their symptoms in the community for a number of days prior to their hospitalisation. In addition, there was significant reduction in these participants’ mobility and daily living. Over the follow-up period, many did not return to their prefracture state and were left more disabled and substantially less mobile. Even at 6 months following their hospital discharge, a substantial proportion was still in severe pain on mobilising. Simple clinical variables on admission did not predict those who did or did not recover.

This observational study has described the natural history of patients admitted to hospital with vertebral fragility fractures. This study was prospective and unselected. Hence, patient outcomes are likely to be representative of UK practice and hospital practice in similar countries, although hospital stay may differ from area to area depending upon local service organisation. This study recruited participants as soon as they presented to hospital and was therefore able to accurately report the impact of their fracture on admission and follow their recovery. This study also recruited participants from one hospital, a tertiary major trauma centre, and the cohort may not necessarily represent patients or the care delivered at other hospitals. Patients admitted here would have access to specialist services such as spinal surgical expertise and possibly earlier musculoskeletal imaging which may have an influence on these patient’s outcomes.

This study confirmed the findings of existing literature that has demonstrated that these patients are frail, elderly and multimorbid [6, 21, 22]. Until now, there was limited information of how pain and disability changed over time after hospitalisation with an acute vertebral fracture. This study has demonstrated that the severe pain, disability and poor mobility persisted over 6 months after a vertebral fracture and that hospital treatment needs to take this into account. These patient’s characteristics and clinical course had a similar progression to patients with vertebral fractures that do not require hospitalisation. These patients were in the eighth decade of life and that up to 4 out of every 5 patients were still in pain and reported deterioration in their quality of life at 12 months after their fracture [23,24,25]. However, it is uncertain how this cohort compared with those admitted to hospital. Another group of patients with poor outcomes that could be compared with hospitalised vertebral fractures are patients admitted to hospital with hip fractures. Similar to the characteristics identified in this study, patients with hip fracture were elderly and frail [26, 27]. With both vertebral and hip fracture, patients reported similar decrease in ability to perform activities of daily living and quality of life in the year following their fracture [28]. Another study reported an eight-fold increase in mortality after a vertebral fracture which was similar to mortality after a hip fracture [29].

Knowledge of how vertebral fragility fractures can affect these patients that require treatment in hospital is needed to design care that is able to meet their needs. From this observational study, besides the acute fracture, these patients have complex physical, mental and health care needs, in particular, pain control and a need for other post-hospital care such as rehabilitation. They are susceptible to poor outcomes, and many even at 6 months after leaving hospital remain symptomatic from their fracture. We concluded from these findings that developing and evaluating a specialist service for this group of patients is justified. A systematic organised model of care, such as an adaptation of orthogeriatric care delivered in hip fracture management which models itself on the principles of comprehensive geriatric assessment, could potentially offer a way of managing these patients [30, 31]. Given the known improved outcome such a model has achieved in hip fracture management, it is plausible that such a service could improve the outcomes of patients hospitalised with vertebral fractures. The next step should be to assess the feasibility of delivering such a specialist service.

References

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J, Cooper C, Kanis JA, Silman AJ (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11(7):1010–1018

Delmas PD, van de Langerijt L, Watts NB, Eastell R, Genant H, Grauer A, Cahall DL, IMPACT Study Group (2005) Underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures is a worldwide problem: The IMPACT Study. J Bone Miner Res 20(4):557–563

Ivergard M, Svedbom A, Hernlund E et al (2013) Epidemiology and economic burden of osteoporosis in UK. Arch Osteoporos 8(137):211–218

Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res 7(2):221–227

Stevenson MD, Davis SE, Kanis JA (2006) The hospitalisation costs and out-patient costs of fragility fractures. Women’s Health Med 3:4

Ong T, Kantachuvesiri P, Sahota O, Gladman JRF (2018) Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with vertebral fragility fractures: a systematic review. Age Ageing 47(1):17–25

Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P et al (2017) Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9, Art. No.:CD006211). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3

Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. [accessed 8 March 2019]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland

Health Research Authority. Mental Capacity Act. NHS Health Research Authority, https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/mental-capacity-act/ [accessed 5 June 2019].

Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM et al (2008) Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 101(1):17–24

Roland M, Fairbank J (2000) The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(24):3115–3124

Collin C, Wade D, Davies S, Horne V (1988) The Barthel ADL Index: A reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 10(2):61–63

Smith R (1994) Validation and reliability of the Elderly Mobility Scale. Physiotherapy 80(11):744–747

Nouri FM, Lincoln NB (1987) An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 1(4):301–305

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173(5):489–495

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V et al (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4):695–699

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA (1986) Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 5(1-2):165–173

Van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, Kohlmann T et al (2012) Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health 15(5):708–715

Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE (2006) Reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ 332(7547):969–971

Clark W, Bird P, Gonski P, Diamond TH, Smerdely P, McNeil H, Schlaphoff G, Bryant C, Barnes E, Gebski V (2016) Safety and efficacy of vertebroplasty for acute painful osteoporosis osteoporotic vertebral (VAPOUR): a multicentre randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 388(10052):1408–1416

Walters S, Chan S, Goh L, Ong T, Sahota O (2016) The prevalence of frailty in patients admitted to hospital with vertebral fragility fractures. Curr Rheumatol Rev 12(3):244–247

Hall S, Myers MA, Sadek A, Baxter M, Griffith C, Dare C, Shenouda E, Nader-Sepahi A (2019) Spinal fractures incurred by a fall from standing height. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 177:106–113

Suzuki N, Ogikubo O, Hansson T (2009) The prognosis for pain, disability, activities of daily living and quality of life after an acute osteoporotic vertebral body fracture: its relation to fracture level, type of fracture and grade of fracture dislocation. Eur Spine J 18(1):77–88

Klazen C, Verhaar H, Lohle P, Lampmann LE, Juttmann JR, Schoemaker MC, van Everdingen K, Muller AF, Mali WP, de Vries J (2010) Clinical course of pain in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21(9):1405–1409

Venmans A, Klazen C, Lohle P, Mali W, van Rooij W (2011) Natural history of pain in patients with conservatively treated osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: results from VERTOS II. Am J Neuroradiol 33(3):519–521

Winters AM, Hartog LC, Roijen HIF, Brohet RM, Kamper AM (2018) Relationship between clinical outcomes and Dutch frailty score among elerly patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Clin Interv Aging 5(13):2481–2486

Krishnan M, Beck S, Havelock W, Eeles E, Hubbard RE, Johansen A (2014) Predicting outcome after hip fracture: using a frailty index to integrate comprehensive geriatric assessment results. Age Ageing 43(1):122–126

Theander E, Jarnlo G, Ornstein E, Karlsson M (2004) Activities of daily living decrease similarly in hospital-treated patients with a hip fracture or a vertebral fracture: a one-year prospective study in 151 patients. Scand J Public Health 32(5):356–360

Cauley JA, Tompson DE, Ensrud KC, Scott JC, Black D (2000) Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int 11(7):556–561

Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL (2014) Ortho-geriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 28(3):e49–e55

Eamer G, Taheri A, Chen SS, Daviduck Q et al (2018) Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1. Art. No.: CD012485). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012485.pub2

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre.

Funding

TO was a recipient of a research fellowship from the Dunhill Medical Trust (RTF49/0114).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TO, JRFG and OSS were involved in the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of these data, drafting the article, revising it and approved the version for submission. TO accepts responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, T., Sahota, O. & Gladman, J.R.F. The Nottingham Spinal Health (NoSH) Study: a cohort study of patients hospitalised with vertebral fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 31, 363–370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05198-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05198-x