Abstract

Summary

This study sought to understand patient experiences, benefits, and challenges to osteoporosis care delivered virtually by telemedicine. Telemedicine bridges the access gap to specialized osteoporosis care in remote areas. Improving coordination of investigations, access to allied health members, and future initiatives may improve osteoporosis-related morbidity and mortality in this population.

Introduction

There is limited research on the role of telemedicine (TM) in the management of osteoporosis (OP). We previously reported that OP patients assessed by TM had a higher prevalence of fragility fractures, co-morbidities, and need for allied health resources than those serviced by the outpatient clinic. The purpose of this study is to understand the experiences, benefits, and challenges associated with receiving OP care by TM from the patient perspective.

Methods

We adopted a convergent, mixed methods study design whereby both a quantitative component (mailed survey) and qualitative component (30-min telephone interviews) were conducted simultaneously. In addition to reporting survey data, thematic analysis was applied to interview data.

Results

Participants were comfortable with virtual technology and perceived that their quality of care by TM was comparable to in-person visits. Expressed benefits included the convenience of timely care close to home, reduced burden of travel and costs, and enhanced sense of confidence with being assessed by an osteoporosis specialist. Perceived barriers included poor follow-up with allied health professionals in the TM program (e.g., physiotherapist) and coordination of tests and investigations. Many participants indicated interest in an OP self-management program, with content focusing on diet and lifestyle factors.

Conclusion

The TM program bridges the access gap for those living with OP in underserviced and remote areas. However, we identified the need to improve the existing processes to better coordinate access to allied health team members and arrangements for investigations. Participants also expressed interest for a virtual osteoporosis self-management program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Osteoporotic fractures, particularly hip fractures are associated with increased mortality and morbidity [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. As such, the primary goal of osteoporosis (OP) management is to reduce the risk of fracture, which involves the consideration of both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic measures [10]. Currently, there is an existing treatment gap in Canada, especially in post-fracture patients.

In Canada, family physicians are primarily responsible for the long-term management of OP, which can be particularly challenging in remote regions where there is a shortage of healthcare providers [11]. These challenges are often compounded by the lack of resources and knowledge on effective OP care, time pressure, and the complexity of the patient population [11].

Telemedicine (TM) is one solution for addressing the burden of OP and treatment gap in remote communities. TM has been shown to be an effective model of healthcare delivery in providing efficient and positive outcomes of chronic diseases including rheumatologic conditions, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [12,13,14]. However, there is a paucity of research on the effectiveness of TM in OP management.

In 2005, a multidisciplinary OP TM program was developed at Women’s College Hospital (WCH) in Toronto, Ontario, to improve access to specialized OP care for underserviced populations in Ontario [15]. The program was developed in conjunction with the Northern Ontario Remote Telehealth Network [16] and was based on the existing outpatient OP clinic at WCH. The clinic model consisted of an assessment by the OP physician and the multidisciplinary allied health team of all new patients at the initial consult encounter [15]. In 2013, both the outpatient and TM program changed its model of care such that the initial encounter of new patients only consists of an assessment by the physician. Assessment by specific allied healthcare providers are scheduled as separate visits based on selective referral by the physician. This change improved the effective use of resources and flexibility in scheduling appointments. We previously reported the high-risk patient characteristics of those serviced by the OP TM program [17], with a higher prevalence of fragility fractures, co-morbidities, and need for allied health resources than those serviced by the outpatient clinic. The primary objective of the current study is to understand the patient experience and the benefits and challenges associated with receiving OP care via TM from the patient perspective.

Methods

We adopted a convergent, mixed methods study design whereby both the quantitative and qualitative components were conducted simultaneously [18]. The quantitative component included a mailed satisfaction survey while the qualitative component involved telephone interviews.

Mixed methods design, participant recruitment, and data collection

Quantitative component

Research ethics approval for both quantitative and qualitative components was obtained from WCH (REB#, 2014-0057-E). A cross-sectional survey design was used for the quantitative component. Completion of a mailed satisfaction survey was voluntary and anonymous. Anonymity and data protection was maintained as study participants were de-identified and assigned numbers.

Eligible participants included all individuals who had at least an initial physician consult encounter with the OP TM program at WCH from 2013 to 2018. Eligible participants were identified from appointment scheduling records from February 19, 2013, to January 31, 2018; a total of 236 surveys were mailed out. The content of the survey was related to patient satisfaction in regards to perceived quality and coordination of care, and comfort with the virtual technology.

Qualitative component

The quantitative survey was followed up with an in-depth interview for the qualitative component [19, 20]. A 30-min semi-structured one-on-one phone interview was held with consenting participants. Eligible participants included individuals who: (1) had at least an initial physician consult encounter with the OP TM program from 2013 to 2018, (2) were English speaking, and (3) did not have cognitive impairment. Participants did not require to have completed the survey to be eligible for the phone interview. Study information and consent form for the telephone interview were included in the mail-out package with the survey. The study coordinator followed up with those who had contacted her with interest in participating in the telephone interview. The study coordinator also called those who had returned completed surveys to elicit interest in participating in the telephone interview. Eligible participants were given the opportunity to ask questions. Verbal consent was sought at the time of the telephone interview, including the willingness to allow linked survey and interview data. If a participant chose not to link their survey and interview data, then their survey data remained anonymous and completely unlinked to their telephone interview. Recruitment ceased as the study approached the point of data saturation [21].

All telephone interviews were completed by the first author (PP), the average length being 35 minutes. The interview guide consisted of semi-structured open-ended questions (Online Resource 1) and was pilot tested with a scientist experienced in qualitative methods (SM) and with an individual with OP. Probes or recursive questions were used to explore issues in greater depth and to verify the interviewer’s understanding of the information being collected [22]. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim for data analysis.

Data analysis and mixed methods integration

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the responses from the Likert scale survey questions, as well as demographic and clinical characteristics of participants who completed the satisfaction survey and/or participated in the interview.

For the qualitative component, inductive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clark was used [21]. We followed all six phases of the approach: after verification of the accuracy of the transcripts by the interviewer (PP), the first two authors (PP, SM) read all transcripts to become familiar with the data. The interview transcripts were initially coded manually by both authors. The codes were then clustered into groups that shared similar meanings. At this point, the two authors met to discuss the coding of the transcripts. New themes were discussed with the rest of the research team. Together, the researchers explored various thematic maps until consensus was reached and theme labels were agreed upon.

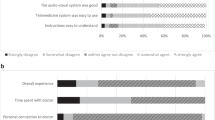

The quantitative and qualitative results were integrated at the interpretation and reporting phases. The findings were then interpreted in sum and were compared to identify complementarity, convergence, and divergence among the data sets [23]. A joint display [23] was used to combine the results, which provided a visual means designed for additional insight in interpreting the data (Fig. 1).

Results

Quantitative component

Survey response and sample characteristics

A total of 236 survey invitations were mailed out. From this, 69 participants responded with completion of the survey; there were 167 surveys with no response. However, 22 of the 167 surveys with no response were found to be not legitimate: 4 were duplicate mailings, 16 were patients who were never assessed in the OP TM program (5 who canceled appointments, 11 who were seen in the outpatient OP clinic instead, 1 who was an endocrine program patient), and 1 was a deceased patient. Therefore, there were a total of 214 eligible participants invited to complete the survey, with 69 responders (response rate of 32.2%) and 145 non-responders.

Table 1 compares the survey responders to the non-responders in terms of the date of the last physician TM encounter and whether they had experienced at least one encounter with an allied health team member. Among the responders, 40/69 (58%) were seen within 1 year of the survey mail-out, compared to 60/145 (41%) of the non-responders. Overall, responders had more interactions with an allied health team member compared to the non-responders (46% vs 38%). Of the 11 responders who had their last TM encounter distantly in 2013–2014, 73% had encounters with an allied health team member.

Selected demographic and clinical characteristics of the survey responders are presented in Table 2. Survey responders had a high prevalence of fragility fracture (38%), moderate/high fracture risk (65.2%), and co-morbidities. The majority of survey participants were female (94%) and the mean age was 66 years.

Patient satisfaction of quality and coordination of care

The responses to the survey are presented in Table 3. Majority of participants were satisfied with the wait time to the initial TM appointment. Eighty-seven percent indicated that they strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “I feel that the quality of care I received at my TM visit was the same as if it had been an in-person visit”; 81% felt comfortable using telemedicine technology. Seventy-five percent strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “My tests were well coordinated with my TM appointment”. Meanwhile, a large proportion (66–78%) either did not respond or indicated “not applicable” when asked about allied health care providers they saw through TM.

Qualitative component

Description of participants

A total of 15 interviews were completed. Demographic, clinical characteristics, and encounter information of the interviewed participants are presented in Table 4. Participants included 14 females and 1 male; mean age was 68 years, slightly older than the survey responders. Interviewed participants had a higher prevalence of fragility fracture, and higher fracture risk profile (80% categorized as moderate or high risk). Similar to survey responders, interviewed participants were complex with multiple co-morbidities. Majority of participants (11 of 15) were recently assessed in the TM OP program. However, only 2 of 15 had an allied health assessment encounter.

Overview of identified themes

We identified four main facilitators and three main barriers to participating in the OP TM program. The four main facilitators were: (1) perceived high quality of care; (2) credibility, expertise, and reassurance of the treating physician; (3) convenience of the program; and (4) comfort with technology. The three main barriers were: (1) poor follow-up with allied health professionals and lack of understanding of their roles, (2) poor coordination of lab tests and bone density tests, and (3) lack of awareness of the TM program. Furthermore, we also identified some preferred components of a self-management program for OP, as a future initiative of the OP TM Program.

Facilitators to participating in the osteoporosis telemedicine program

-

1.

Perceived Quality of Care

Overall, there was a perceived high quality of care among the TM participants in terms of being satisfied with their care and the thorough evaluation they had by the treating physician. When specifically asked about the quality of their care via TM compared to an in-person visit, the majority of participants perceived that there was no difference in the quality of care.

“To me, standing there and talking to somebody on the screen, you get the same quality of service, and maybe better, because they’re focused on me.”—078

“Oh, just the doctor that I was talking with, I thought she was really, really, really good. She hit on different things, I asked different questions, and it was good. I guess it would have been exactly the same if I drove down there and sat with her, but this, to me, it was the convenience.“—193

“I think if I had been sitting in a physical room with the panel I might not have had the attention just because it is human nature to look at a screen these days. They were focused on my response. It wasn’t a long session, but I think it was very thorough.”—189

-

2.

Comfort with Technology

Participants described being comfortable with virtual technology and the set-up process of TM. Many participants also indicated that it was helpful to have the TM appointments conducted in their local TM studio where there would be a nurse or other staff member available to assist with any technological difficulties.

“…because I’m very comfortable with technology. So, it doesn’t scare me or deter me or make me feel uncomfortable.”—078

“We have the technology in our hospital. So, anyway, yes, it got set up and I went, and yeah, no issue with it whatsoever. I was quite satisfied and quite happy that it happened. I did not want to travel on the bus, which is horrific.”—078

-

3.

Credibility, Expertise, and Reassurance of the Treating Physician

Participants in the TM program perceived that the treating physician who delivered their OP care was an expert in the field, and was not only knowledgeable, but also had the capacity and compassion to address their questions and offer them reassurance.

“Number one, the assurance that there’s somebody out there in Never Never Land who knows something more than my GP about osteoporosis.”—235

“To me, I felt like because the person I talked to was in the field in the osteoporosis and that kind of thing so I knew that she was knowing what she was talking about, and then if there would be any concern, that she’ll explain, or act right away, so that my condition won't get worse. And she was very knowledgeable and make sure that I was understanding the terms, too, which I really appreciated…”—214

“And that’s better than being here and being unable to even get a primary care appointment when you need it, much less getting any specialist care locally.”—014

-

4.

Convenience of the Program

The ease of timely care close to home with the TM program was one of the main facilitators of participating in the program. For example, across participants, the average length of time to travel to Toronto would be about 2 h (the range was from 30 min to 5 h), and many in very remote areas would require a full day and night for travel.

“To go downtown Toronto would be like five hours for us. It would mean a night in a motel. I mean, we can fly. You can fly Porter right out of Sudbury, so that’s easy, but costly. And, I have a busy life. I’m not working anymore, I’m retired, but still, there are time constraints and everything.”—077

“There’s no travel time, to speak of, and that’s it. That is the big benefit. No layover, like no overnight stay from home. Being close to home, I guess if I could put it in a few words, being close to home.”—078

“It was easy-peasy. I mean I just go to the hospital here in Manitouwadge, wait, then they show me to a room, this specific room where it’s set up. I’ve had them before with other doctors. It’s quite accessible for us up here.”—235

Thus, a key benefit that was expressed was the reduced burden of travel and costs. For those individuals with OP living in remote area, the cost of travel was described as just as much of a barrier to accessing specialty care in Toronto as is the time and distance of traveling.

“That is the critical thing. I don’t think I could afford to stay overnight. Certainly, not. I wouldn’t want to. And so that’s why I would go so early, you see, so that I could get buses back. Although that doesn’t sound reasonable.”—014

Participants also indicated that weather and traffic would be/have been barriers to receiving care (i.e., if they had to travel to Toronto). Many participants revealed that they would be even less inclined to commute to Toronto in the winter and during traffic. In addition to saving travel time and cost, it is important to note that the patients seen remotely by TM are very complex patients with mobility issues which can create another added barrier to their commute to Toronto.

“I use a walker, a rollator, a fou- foot, four inch leg cane, and a regular cane. Yeah, I have real problems with balance and falling. Leaning over too far into the freezer, I cracked my ribs so it’s pretty bad. They said that after my year thing that my bones had deteriorated very bad in my neck, and when I fell and broke my shoulder, they couldn’t operate because of my health so it’s not a very happy life.”—193

Barriers to participating in the osteoporosis telemedicine program

-

1.

Poor Follow-Up with Allied Health Care Professionals and Poor Understanding of their Roles

The most significant barrier identified was the lack of follow-up with allied health care professionals, with some patients reporting that they never heard back on referred appointments to the allied health team. In addition to lack of follow-up, there was also a lack of understanding from the patient’s perspective about the roles and involvement of the allied health care professionals.

“Because see, they were just going to assess what my needs were, and have the multidisciplinary team contact me, but they never did. The assessment was great, glad to have it, but I had no follow-up.”—158

“Yeah, but I never seen the dietician. The professional … no. When I went to … There was a program that I could go to do exercises and all that, but they start with a stress test and I didn’t pass it. The lady said that she would have called me and I never heard anything.”—214

-

2.

Poor Coordination of Lab Tests and BMD Testing

Most study participants described that there needed to be an improvement in the coordination of tests and bone density testing between the OP TM program, the patient/family doctor and the patient who needs to complete testing in his/her community. The timing of the testing is important because it is imperative to have test results for the follow-up specialist appointment via TM.

“The big problem I had was the coordination of the telemedicine and the blood report, and the timing of the second appointment.”—010

“Yeah, if I have to make the appointment myself, say I've got the letter, say, okay, now you need to go for your bone density at this time of the year, and see the dietician, that you make the appointment yourself, or something, but to be clear on the communication.”—214

-

3.

Perceived Lack of Awareness of the TM Program

Another barrier to accessing the TM program was the perceived lack of awareness that rural family physicians or those patients living in remote areas may have about such a program. Patients indicated that the TM program was a great and convenient option for accessing timely OP care and expressed a desire for more doctors to tell their patients about it.

“I think that doctors maybe need to be more aware of its availability, so that they can inform their patients that it is available. I mean, I have lots of friends that I have talked to that have osteoporosis and they’ve never heard of it.”—077

Recommendation for a self-management program

Towards the end of the interview, participants were educated on what a self-management program is and then asked if they would be interested in such a program for osteoporosis. They were also asked about their preferences in terms of content and delivery of a future self-management program for osteoporosis. The majority of participants indicated an interest in a self-management program designed specifically for OP. Many expressed a desire for content related to diet and exercise and coping with the emotional impact of OP (i.e., having to change your wardrobe, not being to attend social events). Participants also indicated that such a program would provide a successful means of follow-up care. In terms of mode of delivery, participants expressed a desire for online videos. The preference for length of the videos varied from 5 min to 1 h, with the average being 20–30 min in length, and occurring every 3 months. Most of the TM patients indicated a preference for this content to be delivered by an expert professional in that field such as a dietician, physical therapist, or physician. Participants also wanted opportunities to ask questions about specific issues like having a fear of falling. In addition, a few participants indicated that a forum or an opportunity to interact with other community members online may be of benefit. Some participants also expressed a desire for a monthly newsletter.

“Yes, yeah, knowing what is it that’s not too good, or what I should concentrate more on, it would be nice to know. As a balanced diet, too, like, you don’t want to give up something that is important for you. All that information will help a great deal.”—214

“You’ve got to change your entire wardrobe. You’ve got to look for different shoes. My life has changed. And I try and be very positive about it, but there are days when I hit the bottom. That’s difficult. It’s not only difficult for me. It’s difficult for my husband.”—180

“Well, I think the assurance that there’s somebody there that you can talk to or maybe even just write to. Questions. If you seem to be not holding a steady ground and yet you’re doing everything that you could possibly do, yeah, I think it’s time”—235

Discussion

There is a paucity of research focusing on the experiences and satisfaction of individuals participating in a TM program for OP. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the patient perspective of receiving OP care virtually by TM. The integrated results of the quantitative and qualitative phases revealed complementarity and convergence in the areas of quality of care, access to care, and coordination of care. There were no identified areas of divergence between the results of the quantitative and qualitative phases, except for the coordination of tests.

We identified four main facilitators to participating in the OP TM program at WCH including perceived high quality of care, credibility and expertise of the treating physician, and convenience of the program and comfort with technology. The following barriers were identified specific to the OP TM program: poor follow-up with the allied health care team and understanding of their roles, poor coordination of investigations, and the lack of awareness of the OP TM program.

The impact of not receiving timely OP specialist care in high-risk individuals can increase the risk of fragility fractures, thus increasing one’s morbidity and mortality [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Similar to our previously reported cohort of OP TM patients [17], participants of this study were complex with high prevalence of fragility fracture, moderate-to-high fracture risk, and multiple co-morbidities. Therefore, this represents a high-risk cohort who would benefit from timely access to specialist care by TM. In other chronic conditions, TM has shown to have other advantages including enhancing care coordination across various providers, continuity of care, and enabling on-site triage and prompt referral when needed [12].

The most significant barrier identified was the lack of follow-up with allied health professionals. Only 2 of the 15 participants received allied health follow-up, whereas others reported never hearing back on the recommended referral to allied health. This was also consistent with the large proportion of survey responders who either did not respond or indicated “not applicable” when asked about allied health care. This reflects the complexity and resource intensive nature of scheduling TM appointments, which involves matching availability of the patient, clinician, and both hosting and receiving TM studio sites. In response to this feedback, we are piloting the process of ordering allied health referrals through our EMR system, similar to the process in the outpatient clinic, as a trigger to ensure allied health appointments do not fall through the cracks.

Although 75% of the survey responders agreed that tests were well coordinated, interviewed participants expressed poor coordination of investigations. We believe that this discrepancy may be related to the interpretation of the survey question as being coordination of tests prior to the initial TM appointment. Tests prior to the initial TM appointment are standardized in the referral process of our program such that these are included with the referral (e.g., bone density). The poor coordination of investigations expressed by interviewed participants likely reflects the complexity of coordinating additional tests with their follow-up TM encounters. This highlights the need for better processes and protocols to be put in place for the coordination of follow-up TM encounters. We recently implemented the ordering of investigations at the point-of-care during the TM encounter such that test requisitions are faxed to the receiving TM site so that patients have the requisitions at hand, rather than waiting and depending on the family doctor to arrange requested investigations. In addition, we are following up with patients to ensure completion and receipt of ordered tests prior to the follow-up TM encounter. A future evaluation using a randomized control or quasi-experimental design could look not only at patient satisfaction but also improved coordination of care as an outcome in the TM program.

Patients perceived that primary care providers in underserviced areas should be more aware of the availability of the OP TM program. We are presently working on ways to increase the awareness of the OP TM program to better target high-risk patients, such as collaborating with coordinators of Fracture Liaison Services in rural communities.

We identified preferred components of a self-management program for OP that could be considered for integration in the OP TM program. Patients described wanting information about diet, exercise, lifestyle factors, and how to cope emotionally with living with OP, delivered in the format of online videos. Participants also wanted opportunity to ask questions and receive follow-up care. We previously reported on the experiences of participants in a telehealth chronic disease self-management program [24], which showed that a telehealth self-management program could help bridge the access gap and allow for a sense of continuity of care and follow-up for patients in rural settings.

A systematic review [25] identified that people with osteoporosis want information about the nature of osteoporosis/fracture risk, medication, self-management, and understanding the role of bone density test. In contrast to these results, our patients were less interested in learning about the nature of osteoporosis and medication, and more interested lifestyle factors and wellness strategies to cope with the emotional impact of the condition. The OP TM program could fill the gaps identified in terms of providing self-management education and resources, especially if they are delivered online by health care professionals, as desired. Additionally, patients considered regular follow-up with the physician and/or allied health care professionals as one of the most important aspects of their OP management.

Previous evaluations of TM programs have focused on mortality and quality of life in other chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure, diabetes and COPD [12,13,14]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that TM was effective in reducing HbA1C and the risk of moderate hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus [13]. One study [14] systematically reviewed TM for rheumatic diseases and found high feasibility and patient satisfaction, with effectiveness being equal or higher than standard face-to-face approaches. Thus, these findings indicate that TM programs are associated with quality of care outcomes, which matches the perception of high quality care found in our current study. There are limited studies on the cost-effectiveness of TM programs, although there is some evidence to support the economic benefit of TM in terms of reduced hospital admissions, lengths of stay, and emergency visits [12]. Future research should similarly examine the effectiveness of the OP TM program in outcomes such fracture rates and health care utilization. As a future project, we plan to evaluate whether the OP TM program is associated with improved health indicators such as appropriate treatment initiation, adherence, side effect management, and self-management behaviors.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the low response rate (32%) of the mailed survey for the quantitative component, raising the risk of selection bias and uncertainty of generalizability of the findings. In an analysis of 210 studies [26], the mean response rate was 66% with mailed satisfaction surveys, which was higher than previously reported “acceptable” response rates. Response rates were higher when recruitment was done face-to-face. We postulate that one reason for our lower response rate is that our cross-sectional time frame included all patients who had an initial TM encounter over a 5-year period (2013 to 2018). As a result, patients who were last seen many years ago may have not been able to recall their experiences and less likely to participate in the survey, and there is a higher chance that there may have been a change in mailing address. In comparing the responders to non-responders, we found that the successful survey return rate was mostly from recent participants of the TM program, and those who had more TM encounters with assessment by an allied health team member. Although demographic and clinical characteristics of survey responders were similar to our previously reported cohort of OP TM patients [17], we did not examine the demographic and clinical characteristics of the non-responders, and therefore cannot exclude unknown selection bias. We may have been able to improve the response rate if we had sent a reminder to the non-responders. For the qualitative component, although recruitment ceased with data saturation, the sample size was small and therefore raises the possibility of sampling bias.

Conclusions

Our study contributes to an area of limited research on patient perspectives on OP care delivered by TM. Patients participating in TM for their OP management perceived that they were receiving high quality of care that is just as good or even better than in-person care. One of the challenges in healthcare delivery generally, but perhaps even more pronounced in TM, is coordination of care including access to allied health team members and arrangements of investigations. TM programs should consider the importance of coordination of care when designing a successful program. Understanding the patient’s experience with the TM program in terms of barriers, facilitators, and needs in healthcare delivery will assist with future quality improvement initiatives, including the development of a self-management program that is tailored to the unique needs of individuals with osteoporosis. Past research has indicated that programs that are derived from the patient perspective are associated with better outcomes [25]; future research could involve implementing and evaluating the program. Future research should evaluate health outcomes and performance indicators of participants in the OP TM program, comparing to those attending the clinic in person. Such future initiatives hold the potential to improve OP-related morbidity and mortality, especially to individuals in rural and remote regions who would otherwise not receive specialist and tailored services.

References

Brown JP, Josse RG (2002) Scientific Advisory Council of the Osteoporosis Society of Canada. 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. CMAJ 167(10 suppl):S1–34

Poole KE, Compston JE (2006) Osteoporosis and its management. BMJ 333:1251–1256

Greendale GA, Barrett-Connor E, Ingles S, Haile R (1995) Late physical and functional effects of osteoporosis fracture in women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:955–961

Mossey JM, Mutran E, Knott K, Craik R (1989) Determinants of recovery 12 months after hip fracture: the importance of psychosocial factors. Am J Public Health 79:279–286

Marottoli RA, Berkman LF, Cooney LM Jr (1992) Decline in physical function following hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 40:861–866

Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD (1994) Functional recovery after fracture of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76:751–758

Cooper C (1997) The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med 103:12S–17S discussion 17S–19S

Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, Fox KM, Dolan M, Fesenthal G, Kenzora J (2000) Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55A:M498–M507

Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, Eastwood EA, Silberzweig SB, Gilbert M, Morrison RS, McLaughlin M, Orosz G, Siu AL (2001) Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA 285:2736–2742

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal SA, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 182:1864–1873

Jaglal SB, McIsaac WJ, Hawker G, Carroll J, Jaakkimainen L, Cadarette SM, Cameron C, Davis D (2003) Information needs in the management of osteoporosis in family practice: an illustration of the failure of the current guideline implementation process. Osteoporos Int 14:672–676

Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Smith BR et al (2014) The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions for chronic disease management. Telemed J E Health 20(9):769–800

Hu Y, Wen X, Wang F, Yang D, Liu S, Li P, Xu J (2018) Effect of telemedicine intervention on hypoglycemia in diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Telemed Telecare 0(0):1–12

Piga M, Cangemi I, Mathieu A, Cauli A (2017) Telemedicine for patients with rheumatic diseases: systematic review and proposal for research agenda. Semin Arthritis Rheum 47(1):121–128

Dickson L, Cameron C, Hawker G, Ratansi A, Radziunas I, Bansod V, Jaglal S (2008) Development of a multidisciplinary osteoporosis telehealth program. Telemed J E-health 14(5):473–478

Waite K, Silver F, Jaigobin C, Black S, Lee L, Murray B, Danyliuk P, Brown EM (2006) Telestroke: a multi-site, emergency-based telemedicine service in Ontario. J Telemed Telecare 12:141–145

Johnston R, Munce S, Allin S, Pearce A, Silverstein A, Bouchard S, Bereket T, Hawker G, Jaglal S, Kim S (2015) Osteoporosis patients assessed by telemedicine: a unique high risk cohort. J Bone Miner Res 30 (Suppl 1) Available at http://www.asbmr.org/education/AbstractDetail?aid=7416975e-9699-41b6-868a-6ba91ad57578. Accessed [Jan 4, 2018]

Creswell JW, Clark VLP (2017) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications

Sandelowski M (2000) Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 23:334–340

Sandelowski M (2010) What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 33:77–84

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Creswell JW et al (2003) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Curry L, Nunez-Smith M (2015) Mixed methods in health sciences research: a practical primer. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Guilcher SJ, Bereket T, Voth J, Haroun VA, Jaglal SB (2013 Dec) Spanning boundaries into remote communities: an exploration of experiences with telehealth chronic disease self-management programs in rural northern Ontario, Canada. Telemed J E Health 19(12):904–909

Raybould G, Babatunde O, Evans AL, Jordan JL, Paskins Z (2018) Expressed information needs of patients with osteoporosis and/or fragility fractures: a systematic review. Arch Osteoporos 13(1):55

Sitzia J, Wood N (1998) Response rate in patient satisfaction research: an analysis of 210 published studies. Int J Qual Health Care 10(4):311–317

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care for funding the Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy, which provides support for the Osteoporosis Telemedicine Program. The authors thank all the patients of the Osteoporosis Telemedicine Program at Women’s College Hospital, who participated in the study. The authors thank Courtney McLean and Lynn Carter for their administrative assistance with the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 402 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Palcu, P., Munce, S., Jaglal, S.B. et al. Understanding patient experiences and challenges to osteoporosis care delivered virtually by telemedicine: a mixed methods study. Osteoporos Int 31, 351–361 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05182-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05182-5