Abstract

Summary

Patients often do not know or understand their bone density test results, and pharmacological treatment rates are low. In a clinical trial of 7749 patients, we used a tailored patient-activation result letter accompanied by a bone health brochure to improve appropriate pharmacological treatment. Treatment rates, however, did not improve.

Introduction

Patients often do not know or understand their dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) test results, which may lead to suboptimal care. We tested whether usual care augmented by a tailored patient-activation DXA result letter accompanied by an educational brochure would improve guideline-concordant pharmacological treatment compared to usual care only.

Methods

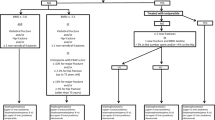

We conducted a randomized, controlled, double-blinded, pragmatic clinical trial at three health care centers in the USA. We randomized 7749 patients ≥50 years old and presenting for DXA between February 2012 and August 2014. The primary clinical endpoint at 12 and 52 weeks post-DXA was receiving guideline-concordant pharmacological treatment. We also examined four of the steps along the pathway from DXA testing to that clinical endpoint, including (1) receiving and (2) understanding their DXA results and (3) having subsequent contact with their provider and (4) discussing their results and options.

Results

Mean age was 66.6 years, 83.8 % were women, and 75.3 % were non-Hispanic whites. Intention-to-treat analyses revealed that guideline-concordant pharmacological treatment was not improved at either 12 weeks (65.1 vs. 64.3 %, p = 0.506) or 52 weeks (65.2 vs. 63.8 %, p = 0.250) post-DXA, even though patients in the intervention group were more likely (all p < 0.001) to recall receiving their DXA results letter at 12 weeks, correctly identify their results at 12 and 52 weeks, have contact with their provider at 52 weeks, and have discussed their results with their provider at 12 and 52 weeks.

Conclusion

A tailored DXA result letter and educational brochure failed to improve guideline-concordant care in patients who received DXA.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Tech Rep Ser 843:1–129

Anonymous (1993) Consensus development conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med 94:646–650

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57

US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

Kanis JA (2002) Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 359:1929–1936

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Strom O, Borgstrom F, Oden A (2008) Case finding for the management of osteoporosis with FRAX—assessment and intervention thresholds for the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:1395–1408

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2010) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29:2520–2526

Nelson HD, Haney EM, Chou R, Dana T, Fu R, Bougatsos C (2010) Screening for osteoporosis: systematic review to update the 2002 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2015) Arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic neck conditions. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Arthritis-Osteoporosis-and-Chronic-Back-Conditions/objectives Accessed 8 Apr 2015

Amarnath AL, Franks P, Robbins JA, Xing G, Fenton JJ (2015) Underuse and overuse of osteoporosis screening in a regional health system: a retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 30:1733–1740

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2015) Your guide to Medicare’s preventive services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Baltimore

National Committee for Quality Assurance (2016) HEDIS 2016. http://www.ncqa.org/hedis-quality-measurement/hedis-measures/hedis-2016 Accessed 13 Apr 2016

Liu Z, Weaver J, de Papp A, Li Z, Martin J, Allen K, Hui S, Imel EA (2016) Disparities in osteoporosis treatments. Osteoporos Int 27:509–519

Cram P, Rosenthal GE, Ohsfeldt R, Wallace RB, Schlechte J, Schiff GD (2005) Failure to recognize and act on abnormal test results: the case of screening bone densitometry. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 31:90–97

Pickney CS, Arnason JA (2005) Correlation between patient recall of bone densitometry results and subsequent treatment adherence. Osteoporos Int 16:1156–1160

Cadarette SM, Beaton DE, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Dickson L, Hawker GA (2007) Minimal error in self-report of having had DXA, but self-report of its results was poor. J Clin Epidemiol 60:1306–1311

Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Johnson JA et al (2012) Interventions to increase osteoporosis treatment in patients with ‘incidentally’ detected vertebral fractures. Am J Med 125:929–936

Ciaschini PM, Straus SE, Dolovich LR et al (2010) Community based intervention to optimize osteoporosis management: randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 10:60

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Bellerose D, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Morrish DW, Maksymowych WP, Rowe BH (2008) Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 178:569–575

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Lier DA et al (2007) Persistence, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to improve the quality of osteoporosis care after a fracture of the wrist: results of a controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 18:261–270

Majumdar SR, Rowe BH, Folk D et al (2004) A controlled trial to increase detection and treatment of osteoporosis in older patients with a wrist fracture. Ann Intern Med 141:366–373

Leslie WD, LaBine L, Klassen P, Dreilich D, Caetano PA (2012) Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 184:290–296

Outman RC, Curtis JR, Locher JL, Allison JJ, Saag KG, Kilgore ML (2012) Improving osteoporosis care in high-risk home health patients through a high-intensity intervention. Contemp Clin Trials 33:206–212

Cranney A, Lam M, Ruhland L, Brison R, Godwin M, Harrison MM, Harrison MB, Anastassiades T, Grimshaw JM, Graham ID (2008) A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with wrist fractures: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int 19:1733–1740

Warriner AH, Outman RC, Feldstein AC et al (2014) Effect of self-referral on bone mineral density testing and osteoporosis treatment. Med Care 52:743–750

Morisky DE, Bowler MH, Finlay JS (1982) An educational and behavioral approach toward increasing patient activation in hypertension management. J Commun Health 7:171–182

Hibbard JH, Greene J (2013) What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff 32:207–214

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M (2004) Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 39:1005–1026

Hibbard J, Gilburt H (2014) Supporting people to manage their health: an introduction to patient activation. The King’s Fund, London

Greene J, Hibbard JH (2012) Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 27:520–526

Marshall R, Beach MC, Saha S, Mori T, Loveless MO, Hibbard JH, Cohn JA, Sharp VL, Korthuis PT (2013) Patient activation and improved outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med 28:668–674

Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, Martin JM, Jack BW, Hibbard JH, Paasche-Orlow MK (2014) Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med 29:349–355

Pilling SA, Williams MB, Brackett RH, Gourley R, Weg MW, Christensen AJ, Kaboli PJ, Reisinger HS (2010) Part I, patient perspective: activating patients to engage their providers in the use of evidence-based medicine: a qualitative evaluation of the VA Project to Implement Diuretics (VAPID). Implement Sci 5:23

Insignia Health (2016) Research studies that use the Patient Activation Measure® (PAM®). http://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/insignia/Research-Studies-Using-PAM.Bibliography.pdf?mtime=20150629140537 Accessed 13 Apr 2016

McLeod KM, McCann SE, Horvath PJ, Wactawski-Wende J (2007) Predictors of change in calcium intake in postmenopausal women after osteoporosis screening. J Nutr 137:1968–1973

Winzenberg T, Oldenburg B, Frendin S, De Wit L, Riley M, Jones G (2006) The effect on behavior and bone mineral density of individualized bone mineral density feedback and educational interventions in premenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 6:12

Edmonds SW, Wolinsky FD, Christensen AJ, Lu X, Jones MP, Roblin DW, Saag KG, Cram P (2013) The PAADRN Study: a design for a randomized controlled practical clinical trial to improve bone health. Contemp Clin Trials 34:90–100

R Development Core Team (2015) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Edmonds SW, Solimeo SL, Lu X, Roblin DW, Saag KG, Cram P (2014) Developing a bone mineral density test result letter to send to patients: a mixed-methods study. Patient Prefer Adherence 8:827–841

Edmonds SW, Cram P, Lu X, Roblin DW, Wright NC, Saag KG, Solimeo SL (2014) Improving bone mineral density reporting to patients with an illustration of personal fracture risk. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 14:101

Edmonds SW, Solimeo SL, Nguyen VT, Wright NC, Roblin DW, Saag KG, Cram P. (2016). Understanding preferences for osteoporosis information to develop an osteoporosis-patient education brochure. Perm J

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Info 42:377–381

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding/support

This work was supported by R01 AG033035 (Cram/Wolinsky) from the NIA at NIH. Dr. Cram is supported by a K24 AR062133 award from NIAMS at the NIH. Dr. Saag is supported by a K24 AR052361 award from the NIAMS at the NIH.

Role of the sponsor

The NIA had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

P. Cram, M. P. Jones, F. D. Wolinsky, S. W. Edmonds, S. F. Hall, Y. Lou, and D. W. Roblin have no conflicts of interest. N. C. Wright has received unrestricted grant support from Amgen for work unrelated to this project. K. G. Saag has received grants from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Merck and has served as a paid consultant to Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Merck unrelated to this project.

Additional information

Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MPH; Sarah L. Morgan, RD, MD, CCD, FACP; Janet A. Schlechte, MD; Jessica H. Williams, MPH, PhD; David J. Zelman, MD

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01507662

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cram, P., Wolinsky, F.D., Lou, Y. et al. Patient-activation and guideline-concordant pharmacological treatment after bone density testing: the PAADRN randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 27, 3513–3524 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3681-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3681-9