Abstract

Summary

Doxorubicin (DOX) is used in pediatric cancer treatment. This study assessed the effects of 7 weeks of DOX and 10-week recovery on bone quality and biomechanical properties in sedentary and exercised Wistar rats. DOX decreases femur diaphysis radial growth and biomechanical properties. Some of these DOX effects were aggravated by exercise.

Introduction

Bone growth in pre-pubertal years critically influences adult fracture risk. DOX is widely used in the treatment of pediatric cancers, but there is limited evidence on its potential negative effects on bone growth. Exercise improves bone growth in children, but there is no evidence if it protects against DOX-induced bone toxicity. This study investigates the early and intermediate effects of a 7-week course of DOX on bone histomorphometry and strength in sedentary and exercised growing animal models.

Methods

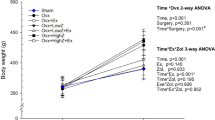

Sixty-eight male Wistar rats (8 weeks) were treated with DOX (2 mg kg−1) or vehicle for 7 weeks and afterward housed in standard cages or in cages with a running wheel and killed 2 or 10 weeks after last DOX administration. Femurs and blood were collected for assaying geometry, trabecular microarchitecture (histology), biomechanical properties (three-point bending and shearing of the femoral neck), bone calcium content and density (atomic absorption spectroscopy), and bone turnover markers (ELISA).

Results

DOX treatment reduced the femur diaphysis radial growth, with DOX-treated animals having a lower tissue area, cortical area, cortical thickness, and moment of inertia. DOX also decreased distal femur trabecular bone volume and trabecular number and increased trabecular separation. Femur diaphysis stiffness and maximum load were also reduced in past DOX-treated animals. Exercise was shown to worsen the effects of past DOX treatment on the femur diaphysis mechanical properties.

Conclusion

DOX negatively affects bone geometry, trabecular microarchitecture, and femur mechanical properties in growing Wistar rats. Exercise further aggravates the detrimental effects of past DOX treatment on bone mechanical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shusterman S, Meadows AT (2000) Long term survivors of childhood leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol 7:217–222

Noguchi C, Miyata H, Sato Y, Iwaki Y, Okuyama S (2011) Evaluation of bone toxicity in various bones of aged rats. J Toxicol Pathol 24:41–48

van Leeuwen BL, Hartel RM, Jansen HW, Kamps WA, Hoekstra HJ (2003) The effect of chemotherapy on the morphology of the growth plate and metaphysis of the growing skeleton. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol 29:49–58

Mwale F, Antoniou J, Heon S, Servant N, Wang C, Kirby GM, Demers CN, Chalifour LE (2005) Gender-dependent reductions in vertebrae length, bone mineral density and content by doxorubicin are not reduced by dexrazoxane in young rats: effect on growth plate and intervertebral discs. Calcif Tissue Int 76:214–221

Rana T, Chakrabarti A, Freeman M, Biswas S (2013) Doxorubicin-mediated bone loss in breast cancer bone metastases is driven by an interplay between oxidative stress and induction of TGFbeta. PLoS One 8:e78043

Buttiglieri S, Ruella M, Risso A, Spatola T, Silengo L, Avvedimento EV, Tarella C (2011) The aging effect of chemotherapy on cultured human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Hematol 39:1171–1181

Friedlaender GE, Tross RB, Doganis AC, Kirkwood JM, Baron R (1984) Effects of chemotherapeutic agents on bone. I. Short-term methotrexate and doxorubicin (adriamycin) treatment in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg 66:602–607

Young DM, Fioravanti JL, Olson HM, Prieur DJ (1975) Chemical and morphologic alterations of rabbit bone induced by adriamycin. Calcif Tissue Res 18:47–63

Glackin CA, Murray EJ, Murray SS (1992) Doxorubicin inhibits differentiation and enhances expression of the helix-loop-helix genes Id and mTwi in mouse osteoblastic cells. Biochem Int 28:67–75

Gewirtz DA (1999) A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol 57:727–741

Chicco AJ, Hydock DS, Schneider CM, Hayward R (2006) Low-intensity exercise training during doxorubicin treatment protects against cardiotoxicity. J Appl Physiol 100:519–527

Behringer M, Gruetzner S, McCourt M, Mester J (2014) Effects of weight-bearing activities on bone mineral content and density in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res 29:467–478

Saarto T, Sievanen H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P et al (2012) Effect of supervised and home exercise training on bone mineral density among breast cancer patients. A 12-month randomised controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 23:1601–1612

Schwartz AL, Winters-Stone K, Gallucci B (2007) Exercise effects on bone mineral density in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 34:627–633

Hydock DS, Parry TL, Wymore JD, Iwaniec UT, Turner RT, Schneider CM, Hayward R (2014) Effects of treadmill training on combined goserelin acetate and doxorubicin-induced osteopenia in female rats. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 14:10–18

Hayward R, Iwaniec UT, Turner RT, Lien CY, Jensen BT, Hydock DS, Schneider CM (2013) Voluntary wheel running in growing rats does not protect against doxorubicin-induced osteopenia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 35:e144–148

National Research Council (U.S.). Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals., Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.), National Academies Press (U.S.) (2011) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Jepsen KJ, Silva MJ, Vashishth D, Guo XE, van der Meulen MC (2015) Establishing biomechanical mechanisms in mouse models: practical guidelines for systematically evaluating phenotypic changes in the diaphyses of long bones. J Bone Miner Res 30:951–966

Turner CH, Burr DB (1993) Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: a tutorial. Bone 14:595–608

Fonseca H, Moreira-Goncalves D, Esteves JL, Viriato N, Vaz M, Mota MP, Duarte JA (2011) Voluntary exercise has long-term in vivo protective effects on osteocyte viability and bone strength following ovariectomy. Calcif Tissue Int 88:443–454

Erben RG, Glosmann M (2012) Histomorphometry in rodents. Methods Mol Biol 816:279–303

D’Haese PC, Van Landeghem GF, Lamberts LV, Bekaert VA, Schrooten I, De Broe ME (1997) Measurement of strontium in serum, urine, bone, and soft tissues by Zeeman atomic absorption spectrometry. Clin Chem 43:121–128

Fonseca H, Moreira-Goncalves D, Vaz M, Fernandes MH, Ferreira R, Amado F, Mota MP, Duarte JA (2012) Changes in proximal femur bone properties following ovariectomy and their association with resistance to fracture. J Bone Miner Metab 30:281–292

Lebrecht D, Setzer B, Ketelsen UP, Haberstroh J, Walker UA (2003) Time-dependent and tissue-specific accumulation of mtDNA and respiratory chain defects in chronic doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Circulation 108:2423–2429

Momparler RL, Karon M, Siegel SE, Avila F (1976) Effect of adriamycin on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in cell-free systems and intact cells. Cancer Res 36:2891–2895

Eliot H, Gianni L, Myers C (1984) Oxidative destruction of DNA by the adriamycin-iron complex. Biochemistry 23:928–936

Ichikawa Y, Ghanefar M, Bayeva M, Wu R, Khechaduri A, Naga Prasad SV, Mutharasan RK, Naik TJ, Ardehali H (2014) Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J Clin Invest 124:617–630

Eom YW, Kim MA, Park SS, Goo MJ, Kwon HJ, Sohn S, Kim WH, Yoon G, Choi KS (2005) Two distinct modes of cell death induced by doxorubicin: apoptosis and cell death through mitotic catastrophe accompanied by senescence-like phenotype. Oncogene 24:4765–4777

Berthiaume JM, Wallace KB (2007) Adriamycin-induced oxidative mitochondrial cardiotoxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol 23:15–25

Bouxsein ML, Karasik D (2006) Bone geometry and skeletal fragility. Curr Osteoporos Rep 4:49–56

Seeman E (2003) Periosteal bone formation—a neglected determinant of bone strength. N Engl J Med 349:320–323

Baxter-Jones AD, Faulkner RA, Forwood MR, Mirwald RL, Bailey DA (2011) Bone mineral accrual from 8 to 30 years of age: an estimation of peak bone mass. J Bone Miner Res 26:1729–1739

Tandon N, Fall CH, Osmond C et al (2012) Growth from birth to adulthood and peak bone mass and density data from the New Delhi Birth Cohort. Osteoporos Int 23:2447–2459

Zebaze RM, Jones A, Knackstedt M, Maalouf G, Seeman E (2007) Construction of the femoral neck during growth determines its strength in old age. J Bone Miner Res 22:1055–1061

Busse B, Djonic D, Milovanovic P, Hahn M, Puschel K, Ritchie RO, Djuric M, Amling M (2010) Decrease in the osteocyte lacunar density accompanied by hypermineralized lacunar occlusion reveals failure and delay of remodeling in aged human bone. Aging Cell 9:1065–1075

Delgado-Calle J, Arozamena J, Garcia-Renedo R, Garcia-Ibarbia C, Pascual-Carra MA, Gonzalez-Macias J, Riancho JA (2011) Osteocyte deficiency in hip fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 89:327–334

Noble BS (2008) The osteocyte lineage. Arch Biochem Biophys 473:106–111

Nilsson M, Ohlsson C, Oden A, Mellstrom D, Lorentzon M (2012) Increased physical activity is associated with enhanced development of peak bone mass in men: a five-year longitudinal study. J Bone Miner Res 27:1206–1214

Burr DB, Martin RB, Schaffler MB, Radin EL (1985) Bone remodeling in response to in vivo fatigue microdamage. J Biomech 18:189–200

Schaffler MB, Radin EL, Burr DB (1989) Mechanical and morphological effects of strain rate on fatigue of compact bone. Bone 10:207–214

Mori S, Burr DB (1993) Increased intracortical remodeling following fatigue damage. Bone 14:103–109

Yadav VK, Oury F, Suda N et al (2009) A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell 138:976–989

Soyka LA, Grinspoon S, Levitsky LL, Herzog DB, Klibanski A (1999) The effects of anorexia nervosa on bone metabolism in female adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:4489–4496

Zanker CL, Swaine IL (2000) Responses of bone turnover markers to repeated endurance running in humans under conditions of energy balance or energy restriction. Eur J Appl Physiol 83:434–440

Morelli D, Menard S, Colnaghi MI, Balsari A (1996) Oral administration of anti-doxorubicin monoclonal antibody prevents chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity in mice. Cancer Res 56:2082–2085

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Celeste Resende for her technical support regarding animal care and to Teresa Caldeira for her technical support with the atomic absorption spectroscopy. The Research Centre on Physical Activity Health and Leisure (CIAFEL) is supported by UID/DTP/00617/2013. HF and DMG were supported by individual grants from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) SFRH/BPD/78259/2011 and SFRH/BPD/90010/2012, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fonseca, H., Carvalho, A., Esteves, J. et al. Effects of doxorubicin administration on bone strength and quality in sedentary and physically active Wistar rats. Osteoporos Int 27, 3465–3475 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3672-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3672-x