Abstract

Summary

In our qualitative study, men with fragility fractures described their spouses as playing an integral role in their health behaviours. Men also described taking risks, preferring not to dwell on the meaning of the fracture and/or their bone health. Communication strategies specific to men about bone health should be developed.

Introduction

We examined men’s experiences and behaviours regarding bone health after a fragility fracture.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of five qualitative studies. In each primary study, male and female participants were interviewed for 1–2 h and asked to describe recommendations they had received for bone health and what they were doing about those recommendations. Maintaining the phenomenological approach of the primary studies, the transcripts of all male participants were re-analyzed to highlight experiences and behaviours particular to men.

Results

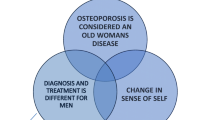

Twenty-two men (50–88 years old) were identified. Sixteen lived with a wife, male partner, or family member and the remaining participants lived alone. Participants had sustained hip fractures (n = 7), wrist fractures (n = 5), vertebral fractures (n = 2) and fractures at other locations (n = 8). Fourteen were taking antiresorptive medication at the time of the interview. In general, men with a wife/female partner described these women as playing an integral role in their health behaviours, such as removing tripping hazards and organizing their medication regimen. While participants described giving up activities due to their bone health, they also described taking risks such as drinking too much alcohol and climbing ladders or deliberately refusing to adhere to bone health recommendations. Finally, men did not dwell on the meaning of the fracture and/or their bone health.

Conclusions

Behaviours consistent with those shown in other studies on men were described by our sample. We recommend that future research address these findings in more detail so that communication strategies specific to men about bone health be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HGM, Cooper C (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 29(6):517–522

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (1999) Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353(9156):878–882

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2010) Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing 39:203–209

Trombetti A, Herrmann F, Hoffmeyer P, Schurch MA, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R (2002) Survival and potential years of life lost after hip fracture in men and age-matched women. Osteoporos Int 13:731–737

Mikyas Y, Agodoa I, Yurgin N (2014) A systematic review of osteoporosis medication adherence and osteoporosis-related fracture costs in men. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 12:267–277

Christensen L, Iqbal S, Macarios D, Badamgarav E, Harley C (2010) Cost of fractures commonly associated with osteoporosis in a managed-care population. J Med Econ 13(2):302–313

Sedlak CA, Doheny MO, Estok PJ (2000) Osteoporosis in older men: knowledge and health beliefs. Orthop Nurs 19(3):38–42

Gaines JM, Marx KA (2011) Older men’s knowledge about osteoporosis and educational interventions to increase osteoporosis knowledge in older men: a systematic review. Maturitas 68:5–12

Cindas A, Savas S (2004) What do men who are at risk of osteoporosis know about osteoporosis in developing countries? Scand J Caring Sci 18:188–192

Raphael HM, Gibson BJ, Lathlean JA, Walker JM (2009) A grounded theory study of men’s perceptions and experience of osteoporosis. Bone 44(2):s200–s201

Ali NS, Shonk C, El-Sayed MS (2009) Bone health in men: influencing factors. Am J Health Behav 33(2):213–222

Tung WC, Lee IFK (2006) Effects of an osteoporosis educational programme for men. J Adv Nurs 56(1):26–34

Doheny MO, Sedlak CA, Hall RJ, Estok PJ (2010) Structural model for osteoporosis preventing behavior in men. Am J Mens Health 4(4):334–343

Cheng N, Green ME (2008) Osteoporosis screening for men. Are family physicians following the guidelines? Can Fam Physician 54(8):1140–1141

Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, Weir DL, Bellerose D, Hanley DA et al (2014) Critical impact of patient knowledge and bone density testing on starting osteoporosis treatment after fragility fracture: secondary analysis from two controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 25:2173–2179

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, Gao Y, Sawka AM, Goltzman D et al (2008) The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 19:581–587

Fraser LA, Ioannidis G, Adachi JD, Pickard L, Kaiser SM, Prior J et al (2011) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap in women: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 22(3):789–796

Liu Z, Weaver J, de Papp A, Li Z, Martin J, Allen K et al (2016) Disparities in osteoporosis treatments. Osteoporos Int 27:509–519

McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM (2003) Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res 18(2):156–170

Schwandt TA (2001) Dictionary of qualitative inquiry, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA

Sokolowski R (2000) Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kvale S, Brinkmann S (2009) Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing, 2nd edn. Sage Publications Ltd., Thousand Oaks

Moustakas C (1994) Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Polkinghorne DE (1989) Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology. In: Valle RS, Halling S (eds) Phenomenological research methods. Plenum Press, New York, pp 41–60

Kralik D, Koch T, Price K, Howard N (2004) Chronic illness self-management: taking action to create order. J Clin Nurs 13(2):259–267

Thorne S, Paterson B, Russell C (2003) The structure of everyday self-care decision making in chronic illness. Qual Health Res 13(10):1337–1352

Giorgi A (2008) Concerning a serious misunderstanding of the essence of the phenomenological method in psychology. J Phenomenol Psychol 39:33–58

Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM (2006) Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 88(1):25–34

Jaglal SB, Hawker G, Cameron C, Canavan J, Beaton D, Bogoch E et al (2010) The Ontario osteoporosis strategy: implementation of a population-based osteoporosis action plan in Canada. Osteoporos Int 21:903–908

Sale JEM, Gignac MA, Hawker G, Beaton D, Frankel L, Bogoch E et al (2016) Patients do not have a consistent understanding of high risk for future fracture: a qualitative study of patients from a post-fracture secondary prevention program. Osteoporos Int 27:65–73

Sale JEM, Bogoch E, Hawker G, Gignac M, Beaton D, Jaglal S et al (2014) Patient perceptions of provider barriers to post-fracture secondary prevention. Osteoporos Int 25:2581–2589

Sale J, Gignac M, Hawker G, Frankel L, Beaton D, Bogoch E et al (2011) Decision to take osteoporosis medication in patients who have had a fracture and are ‘high’ risk for future fracture. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:92

Sale JEM, Beaton D, Fraenkel L, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch E (2010) The BMD muddle: the disconnect between bone densitometry results and perception of bone health. J Clin Densitom 13(4):370–378

Sale JEM, Hawker G, Cameron C, Bogoch E, Jain R, Beaton D et al (2015) Perceived messages about bone health after a fracture are not consistent across health care providers. Rheumatol Int 35(1):97–103

Heaton J (2008) Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Hist Social Res 33(3):33–45

Hinds PS, Vogel RJ, Clarke-Steffen L (1997) The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qual Health Res 7(3):408–424

Nvivo [computer program]. Victoria, Australia: Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty Ltd.; 2010.

Giorgi A (1997) The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. J Phenomenol Psychol 28:235–260

Wertz FJ (2005) Phenomenological research methods for counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol 52(2):167–177

Giorgi A (1989) Some theoretical and practical issues regarding the psychological phenomenological method. Saybrook Rev 7:71–85

Patton MQ (1999) Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 34(5 Part II):1189–1208

Creswell JW (1998) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Norcross WA, Palinkas LA, Ramirez C (1996) The influence of women on the health care-seeking behavior of men. J Fam Pract 43(5):475–480

Griffith DM, Wooley AM, Allen JO (2013) I’m ready to eat and grab whatever I can get: determinants and patterns of African American men’s eating practices. Health Promot Pract 14(2):181–188

O’Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G (2005) It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med 61:503–516

Gray RE, Fitch M, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Fergus K (2000) Managing the impact of illness: the experiences of men with prostate cancer and their spouses. J Health Psychol 5(4):531–548

Giorgianni SJ, Porche DJ, Williams ST, Matope JH, Leonard BL (2013) Developing the discipline and practice of comprehensive men’s health. Am J Mens Health 7(4):342–349

Gilson K-M, Bryant C, Judd F (2014) Exploring risky drinking and knowledge of safe drinking guidelines in older adults. Subst Use Misuse 49:1473–1479

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Cawthon PM, Bauer DC, Fink HA, Schousboe JT, et al. (2015) Degree of trauma differs for major osteoporotic fracture events in older men versus older women. J Bone Mineral Res; in press.

Patel A, Coates PS, Nelson JB, Trump DL, Resnick NM, Greenspan SL (2003) Does bone mineral density and knowledge influence health-related behaviors of elderly men at risk for osteoporosis? J Clin Densitom 6(4):323–329

Sale JEM, Cameron C, Hawker G, Jaglal S, Funnell L, Jain R et al (2014) Strategies use by an osteoporosis patient group to navigate for bone health care after a fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 134:229–235

Gignac MA, Cott C, Badley EM (2002) Adaptation to disability: applying selective optimization with compensation to the behaviors of older adults with osteoarthritis. Psychol Aging 17(3):520–524

Gignac MAM, Cott C, Badley EM (2000) Adaptation to chronic illness and disability and its relationship to perceptions of independence and dependence. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci 55B(6):362–372

Rice RE (2006) Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int J Med Inform 75:8–28

Addis ME, Mahalik JR (2003) Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol 58(1):5–14

Benetou V, Orfanos P, Feskanich D, Michaelsson K, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Ahmed LA et al (2015) Education, marital status, and risk of hip fractures in older men and women: the CHANCES project. Osteoporos Int 26:1733–1746

Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP (2011) A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health 26(11):1479–1498

Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA (2004) The problem of appraising qualitative research. Quality Saf Health Care 13:223–225

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (MOP—119522; CBO-109629; IMH—102813; CGA—86802) and by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) as part of the evaluation of the Fracture Clinic Screening Program of the Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy. Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not reflect the opinions of the MOHLTC. Joanna Sale was, in part, funded by a CIHR New Investigator Salary Award (COB—136622). Maureen Ashe acknowledges funding from CIHR and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research career awards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sale, J.E.M., Ashe, M.C., Beaton, D. et al. Men’s health-seeking behaviours regarding bone health after a fragility fracture: a secondary analysis of qualitative data. Osteoporos Int 27, 3113–3119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3641-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3641-4