Abstract

Summary

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of once-weekly teriparatide as a function of baseline fracture risk. Treatment with once-weekly teriparatide was associated with a statistically significant 79 % decrease in vertebral fractures, and in the cohort as a whole, efficacy was not related to baseline fracture risk.

Introduction

Previous studies have suggested that the efficacy of some interventions may be greater in the segment of the population at highest fracture risk as assessed by the FRAX® algorithms. The aim of the present study was to determine whether the antifracture efficacy of weekly teriparatide was dependent on the magnitude of fracture risk.

Methods

Baseline fracture probabilities (using FRAX) were computed from the primary data of a phase 3 study (TOWER) of the effects of weekly teriparatide in 542 men and postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. The outcome variable comprised morphometric vertebral fractures. Interactions between fracture probability and efficacy were explored by Poisson regression.

Results

The 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fractures (without BMD) ranged from 7.2 to 42.2 %. FRAX-based hip fracture probabilities ranged from 0.9 to 29.3 %. Treatment with teriparatide was associated with a 79 % (95 % CI 52–91 %) decrease in vertebral fractures assessed by semiquantitative morphometry. Relative risk reductions for the effect of teriparatide on the fracture outcome did not change significantly across the range of fracture probabilities (p = 0.28). In a subgroup analysis of 346 (64 %) participants who had FRAX probabilities calculated with the inclusion of BMD, there was a small but significant interaction (p = 0.028) between efficacy and baseline fracture probability such that high fracture probabilities were associated with lower efficacy.

Conclusion

Weekly teriparatide significantly decreased the risk of morphometric vertebral fractures in men and postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Overall, the efficacy of teriparatide was not dependent on the level of fracture risk assessed by FRAX in the cohort as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The continuous endogenous production of excess parathyroid hormone (PTH), as seen in primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, or its exogenous administration, may give rise to deleterious consequences for the skeleton, particularly in cortical bone. However, intermittent administration of PTH (e.g., with daily or weekly subcutaneous injections) results in an increase of the number and activity of osteoblasts, leading to an increase in bone mass and in an improvement in skeletal architecture at both cancellous and cortical skeletal sites [1–3]. The intact molecule (amino acids 1–84) and the 1–34 N-terminal fragment (teriparatide) are used in the management of osteoporosis [4]. Treatment with either agent has been shown to reduce significantly the risk of vertebral fractures, whereas teriparatide has also been shown to have an effect on nonvertebral fractures [5–9]. Beneficial effects on nonvertebral fracture with teriparatide have been shown to persist for up to 30 months after stopping treatment [10].

Several studies have examined the interaction between FRAX-based probabilities at baseline and subsequent effectiveness. Three of these reanalyses of clinical trial data have shown greater efficacy against fracture in individuals at higher risk treated with clodronate or bazedoxifene [11–13] whereas others have shown stable benefits of strontium ranelate or raloxifene across a range of fracture probabilities (but with greater absolute risk reductions in those at higher risk) [13–15]. In a further preplanned analysis of the FREEDOM trial, greater efficacy against fracture was shown in individuals at higher risk treated with denosumab [16]. No data are available for teriparatide or PTH.

Against this background, the aim of the present study was to seek interactions between teriparatide-induced effects on fracture and baseline fracture probability determined by FRAX® as now requested for new phase 3 studies by the European regulatory body [17]. The hypothesis tested was that weekly teriparatide reduced the risk of fracture irrespective of pretreatment fracture probability.

Methods

TOWER study

The Teriparatide Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial, conducted in Japan, was a randomized phase 3 double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effects of once-weekly teriparatide on the risk of vertebral fracture. The details have been previously published [9]. In brief, men and postmenopausal women aged between 65 and 95 years were eligible for the study if they had one to five vertebral fractures and low bone mineral density (BMD). Morphometric vertebral fractures at baseline were identified using semiquantitative (SQ) and quantitative assessments [18]. Prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline was defined as a 20 % or greater reduction in the vertebral height in any of the anterior, posterior, or central vertebral heights, or from corresponding values in the adjacent upper or lower vertebra. Low BMD was defined as <80 % of the young adult mean value at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, or distal radius measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. At the femoral neck, this corresponds to a T-score of < −1.67 SD, using the NHANES young female reference range [19]. In participants who did not undergo DXA measurement, bone mass was assessed by second metacarpal radiogrammetry, with low BMD again defined as <80 % young adult mean.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive weekly subcutaneous injections of teriparatide 56.5 μg or placebo for 72 weeks in a 1:1 ratio. All subjects received daily oral supplements of calcium 610 mg, vitamin D 400 IU, and magnesium 30 mg. The primary outcome variable was vertebral fracture assessed from radiographs taken at 24, 48, and 72 weeks. An incident fracture was identified by an increase of at least one SQ grade and a 20 % or greater decrease from baseline of vertebral height in any of the anterior, posterior, or central vertebral heights.

The study enrolled 578 men and women, and data were available in 542 for analysis. Treatment with once-weekly teriparatide reduced the incidence of vertebral fractures compared to placebo (relative risk: 0.20; 95 % CI: 0.09–0.45; p < 0.01) [9].

Assessment of fracture probability

The 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical spine, forearm, humerus, or hip fracture) and of a hip fracture was computed using the Japanese FRAX® model (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) (version 3.8) [20, 21]. The primary analysis used baseline 10-year probability of major fracture. For each probability, calculations were made using information on the clinical risk factors alone since femoral neck BMD was available in only a subset of patients (64 %). In an additional analysis, we also examined the 10-year probability of hip fracture as a risk variable. In a subgroup analysis, we calculated fracture probabilities that included femoral neck BMD.

Probability of fracture was calculated in men or women from age, body mass index (BMI) computed from height and weight, and dichotomized risk variables that comprised a prior fragility fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current tobacco smoking, ever long-term use of oral glucocorticoids, rheumatoid arthritis, other causes of secondary osteoporosis, and daily alcohol consumption of 3 or more units daily. Information on sex, age, BMI, and previous fracture was available in all patients. Past use of glucocorticoids, rheumatoid arthritis, and other secondary causes of osteoporosis were exclusion criteria, and a “no” response was entered. There was no information available for parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, and alcohol intake, and these variables was set to no for all subjects.

In the subgroup in which femoral neck BMD was available, BMD was additionally entered to yield the 10-year probabilities as defined above with the inclusion of BMD. BMD was measured using equipment from two different manufacturers (Hologic and GE-Lunar). BMD were standardized [22], and T-scores were computed from the NHANES young female reference range [19].

Statistical methods

This was an intention to treat (ITT) analysis. For the effects of teriparatide on fracture outcomes, an extension of Poisson regression model was used [23]. In contrast to logistic regression, the Poisson regression utilizes the length of each individual’s follow-up period, and the hazard function is assumed to be exp (β0 + β1 · time from baseline + β2 · current age + β3 · current variable of interest). The observation period of each participant was divided in intervals of 1 month. One fracture per person was counted.

For the assessment of overall efficacy, the following regression model was used: (1) constant, (2) current time, (3) current age, (4) treatment (teriparatide versus placebo, where 1 = teriparatide and 0 = placebo).

The interaction between treatment and 10-year probability was examined with the model: (1) constant, (2) current time, (3) current age, (4) treatment (teriparatide versus placebo), (5) 10-year probability, (6) treatment × 10-year probability.

Hazard ratios (HR) for treatment effect and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) were computed as a continuous variable. For ease of presentation in tables, % relative risk reduction (RRR = 100 − hazard ratio*100) is shown at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile of fracture probability. Two-sided p values were used for all analyses and p < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Results

A total number of 542 men and women were studied aged 65–90 years (mean age 75.4 years, SD 5.8 years; median age 75 years, IQR 71 to 79 years) of whom 96 % were female. BMI ranged from 15 to 37 kg/m2 (mean 23.0 kg/m2, SD 3.3 kg/m2). Forty-four patients sustained a new vertebral fracture identified by vertebral morphometry.

Summary effects of treatment

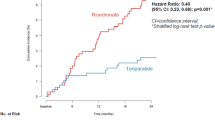

Overall, once-weekly teriparatide was associated with a statistically significant 79 % decrease in morphometric vertebral fractures (HR 0.21; 95 % CI 0.09–0.48).

10-year fracture probability

For each patient, the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical spine, hip, forearm, and humerus fracture) was calculated using FRAX without BMD. Mean probabilities are shown in Table 1, together with probabilities for hip fracture. The 10-year probability of a major fracture ranged from 7.2 to 42.2 %, with 3.7 % participants having a probability ≤10 %. A similar range was observed in the subset with BMD available to be included in the FRAX calculations, where 2.6 % had a probability of major fracture ≤10 %.

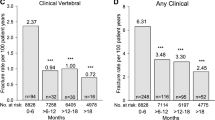

Interaction between treatment and fracture probability

Table 2 shows the effect of teriparatide at different percentiles of FRAX probabilities for a major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture calculated without BMD (n = 542). The relative risk reduction (RRR) tended to decrease with increasing fracture probability, but the interaction between treatment effect and fracture probability was not significant (p = 0.28). The relationship is shown as a continuous function in Fig. 1 and at given percentiles of baseline probability in Table 2. Although there was a suggestion that lower age was associated with increased efficacy, the test for interaction did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.24).

Hip fracture probability

Mean probabilities of hip fracture at baseline are shown in Table 1. The 10-year probability of a hip fracture ranged from 0.9 to 29.3 %. As was the case for the probability of a major fracture, efficacy tended to decrease with increasing fracture probability (Table 3), but the interaction between treatment effect and fracture probability was not statistically significant (p > 0.30).

Subgroup analysis

A total of 542 men and women were studied, of whom all had information on the clinical risk factors. Of these, 346 (64 %) had additional information on BMD, and 196 (36 %) were included on the basis of metacarpal radiogrammetric measures. The mean T-score for BMD at the femoral neck was −2.8 ± 0.7 SD and ranged from −4.7 to −0.9 SD. Mean age was slightly lower in patients with a DXA BMD test than in those without [74.9 ± 5.8 years versus 76.1 ± 5.7 (p = 0.031)]. BMI was similar in the two groups (23.0 ± 3.2 versus 22.8 ± 3.5 kg/m2, respectively; p > 0.30). In the subgroup in which BMD was measured, new vertebral fractures were noted in 27 patients. The effect of weekly teriparatide on vertebral fracture risk was similar to that observed in the entire population (HR: 0.20; 95 % CI: 0.07–0.57).

In this subgroup with DXA BMD measured, the mean probability of a major fracture was 26.0 %, marginally higher than for the entire population (see Table 2). Table 4 demonstrates the effects of teriparatide at different percentiles of FRAX probabilities for a major osteoporotic fracture calculated with BMD. There was a statistically significant interaction between FRAX probability and efficacy (p = 0.028), such that high major osteoporotic fracture probabilities were associated with lower efficacy. This appeared to be driven by much lower apparent efficacy in the population above the 90th centile for baseline fracture probability. However, the 95 % CI around the efficacy point estimate in this group spanned from a risk increase to an RRR of 85 %. Apart from the 90 % centile, the effect was quantitatively similar to that observed in the absence of BMD in the FRAX model. For example, the RRR for fracture probabilities with BMD at the 25th and 75th centiles were 95 and 79 %, respectively (Table 4). The corresponding RRRs at probabilities without BMD were 87 and 71 % (Table 2). When associations were examined in the group who had undergone DXA BMD measurement, but without inclusion of BMD in the model, the interaction term did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.13), raising the possibility of a BMD-efficacy interaction. This interaction was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.055) and documented in Table 5. When the analysis was restricted to those individuals who were included on the basis of metacarpal radiogrammetry, there was again no evidence of an interaction between treatment and baseline risk for fracture occurrence (p = 0.30).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated a marked effect of teriparatide given weekly on the occurrence of new vertebral fractures, with a relative risk reduction of 79 %, consistent with previous findings in this cohort [9], and others relating to both weekly [6] and daily teriparatide [7]. However, in this current analysis, there was no evidence of a significant interaction between fracture probability and efficacy in the cohort as a whole. There was a small but statistically significant interaction between efficacy and baseline fracture probability calculated with inclusion of BMD, in the sense that marginally lower efficacy was evident at higher fracture probabilities. This appeared to be a consequence of an interaction between efficacy and BMD, driven by the subgroup of participants in the lowest 10 % of BMD and highest 10 % baseline fracture risk.

Earlier studies of raloxifene [13, 14] and strontium ranelate [15] yielded similar findings with respect to a lack of variation in efficacy according to baseline fracture probability. However, they contrast with results from reanalysis of two other phase III studies [11, 12]. In the first of these, a marked trend toward greater fracture reduction at higher baseline fracture probability was observed in a 3-year prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oral clodronate in elderly women, identified from general practice registers. When BMD was excluded from the calculation of probability, the interaction was statistically significant [11], and there was some evidence of a threshold with efficacy apparent at fracture probabilities exceeding 20 %. These data are complemented by findings of a significant effect of bazedoxifene on clinical fractures with fracture probabilities that exceeded 17 % [12]. More recently, evidence of a similar interaction between efficacy and baseline fracture probability has been reported for denosumab [16].

In the current analysis, there was evidence, albeit not achieving statistical significance, of greater efficacy among younger participants, consistent with other recent findings [24]. Indeed, we also found, in the subgroup in whom DXA BMD measures were included in the FRAX calculation, that efficacy appeared lower in those with lowest BMD (and who tended to be older). Interestingly, the treatment-induced increase in lumbar spine BMD in this trial somewhat lower than that in the pivotal study of the daily medication (6.4 versus 9.7 %) [7]. However, given that our analysis was within one trial and the constraints of a non-head-to-head comparison and different study populations, this is unlikely to explain our results. As the efficacy-BMD interaction was driven primarily by those individuals in the top 10 % of fracture probability and lowest 10 % of BMD, with efficacy in the remainder of the population similar across the distribution and in those with or without BMD measures, we view this observation as of interest but requiring confirmation. Additionally, the definition of incident vertebral fracture differed between the TOWER trial and the pivotal trial of daily teriparatide. Although a similar SQ approach was employed in both trials, in the latter study, new fractures were only considered in previously normal vertebrae, and analyses conducted separately for all and moderate/severe fractures; in the TOWER trial, worsening of pre-existing fractures was considered if the change was by at least one SQ grade and by >20 %. These different approaches may lead to variation in the magnitude of treatment effect demonstrated, but as they are consistent between treatment and placebo groups within each study, there is no reason to suppose that they would influence interactions between baseline risk and treatment [25].

Patients included in the TOWER trial of weekly teriparatide had relatively high pre-treatment fracture risks. Indeed, only 3.6 % had a baseline probability of major fracture ≤10 %. It is possible, therefore, that any attenuation of efficacy with low fracture probabilities might be seen in patients at much lower risk than those recruited to TOWER. In the present analysis, the mean 10-year probability of a major fracture calculated using FRAX including BMD was 26 %. This compares with 21 % in the raloxifene study [14], in which no fracture probability-efficacy interaction was documented, but contrasts with the lower value of 10.9 % in the analysis of bazedoxifene [12], in which an interaction between antifracture efficacy and baseline fracture probability was observed. However, in the clodronate study [11], where an interaction was found, the mean probability was 18 %, although the overall range of probabilities was greater. Further analyses of phase 3 studies with a mean baseline fracture probability toward the lower part of the overall distribution may help to clarify such findings.

There are a number of limitations to this study that should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, the TOWER Trial included relatively few incident fractures (n = 44), with the number of vertebral fractures in study participants with a DXA BMD test even fewer (n = 27). Indeed, the criterion for low bone mass was the equivalent of a T-score of −1.67, rather than −2.0 or −2.5, the threshold commonly used in phase 3 studies. However, this approach represents the country norm in Japan, and since we examined relationships across BMD in a continuous fashion, this should not have affected our results; the higher BMD criterion may have reduced our capacity to elucidate relationships between BMD and efficacy at the very lowest T-scores. Furthermore, although the relationship between metacarpal radiogrammetry and vertebral fracture risk is uncertain in this population, the results in the subset who underwent radiogrammetry instead of DXA appeared similar to those in the whole trial cohort. Second, the sole outcome of the TOWER study was vertebral fracture. Thus, it is uncertain whether the same relationship between efficacy and fracture probability would be observed with the inclusion of other fracture outcomes, although congruence between vertebral and nonvertebral fracture outcomes has been documented in other studies [12, 15]. Third, several FRAX risk variables (parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, and alcohol intake) were not recorded in the original TOWER trial. These were set to missing in the current analysis, but, owing to the randomized allocation of patients to treatment or placebo, this is unlikely to have biased baseline risk calculations differentially across the two groups. However, this may have resulted in an underestimation of fracture probability overall, and the possibility of a differential effect across groups remains. Finally, the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture rather than hip fracture was used as the index of fracture risk, since it was found to be more closely related to the fracture occurrence. However, in a sensitivity analysis using baseline probability for hip fracture, results were extremely similar.

In conclusion, this analysis has demonstrated, consistent with previous findings, that treatment with teriparatide once weekly is associated with a marked decrease in morphometric vertebral fractures compared to treatment with placebo. However, in the cohort as a whole, there was no evidence of an interaction between efficacy and baseline fracture probability. Although the potential interaction between efficacy and DXA BMD might support an initiation strategy predicated on stratification by baseline BMD, these findings require replication in further studies, ideally both of daily and weekly teriparatide, before they can be confidently incorporated into any formal policy. Overall, these findings do not provide support for the stratification of weekly teriparatide prescription according to baseline fracture risk.

References

Reeve J, Meunier PJ, Parsons JA et al (1980) Anabolic effect of human parathyroid hormone fragment on trabecular bone in involutional osteoporosis: a multicentre trial. Br Med J 280:1340–1344

Devogelaer JP, Boutsen Y, Manicourt DH (2010) Biologicals in osteoporosis: teriparatide and parathyroid hormone in women and men. Curr Osteoporos Rep 8:154–161

Resmini G, Iolascon G (2011) New insights into the role of teriparatide. Aging Clin Exp Res 23(2 Suppl):30–32

Kanis JA McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster J-Y, on behalf of the Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) and the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57

Vescini F, Grimaldi F (2012) PTH 1-84: bone rebuilding as a target for the therapy of severe osteoporosis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 9:31–36

Fujita T, Fukunaga M, Itabashi A, Tsutani K, Nakamura T (2014) Once-weekly injection of low-dose teriparatide (28.2 μg) reduced the risk of vertebral fracture in patients with primary osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 94(2):170–175

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR et al (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441

Shrader SP, Ragucci KR (2005) Parathyroid hormone (1-84) and treatment of osteoporosis. Ann Pharmacother 39:1511–1516

Nakamura T, Sugimoto T, Nakano T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Yoshikawa H, Nishizawa Y, Fujita T, Shiraki M (2012) Randomized Teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (TERIPARATIDE) 1-34] Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial for examining the reduction in new vertebral fractures in subjects with primary osteoporosis and high fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:3097–3106

Prince R, Sipos A, Hossain A, Syversen U, Ish-Shalom S, Marcinowska E, Halse J, Lindsay R, Dalsky GP, Mitlak BH (2005) Sustained nonvertebral fragility fracture risk reduction after discontinuation of teriparatide treatment. J Bone Miner Res 20:1507–1513

McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Vasireddy S, Kayan K, Pande K, Jalava T, Kanis JA (2009) Ten-year fracture probability identifies women who will benefit from clodronate therapy–additional results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised study. Osteoporos Int 20:811–817

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A et al (2009) Bazedoxifene reduces vertebral and clinical fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk assessed with FRAX. Bone 44:1049–1054

Kim K, Svedbom A, Luo X, Sutradhar S, Kanis JA (2014) Comparative cost-effectiveness of bazedoxifene and raloxifene in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Europe using the FRAX algorithm. Osteoporos Int 25:325–337

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Odén A et al (2010) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of raloxifene on all clinical and vertebral fractures and its dependency on FRAX. Bone 47:729–735

Kanis JA, Jönsson B, Odén A, McCloskey EV (2011) A meta-analysis of the effect of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fracture in postmenopausal osteoporosis and the interaction with FRAX®. Osteoporos Int 22:2347–2355, with erratum Osteoporos Int. 22: 2357-2358

McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Austin M, Siris E, Wang A, Lewiecki EM, Lorenc R, Libanati C, Kanis JA (2012) Denosumab reduces the risk of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women, particularly in those with moderate to high fracture risk as assessed with FRAX. J Bone Miner Res 27:1480–1486

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) (2006) Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products in the treatment of primary osteoporosis. Ref CPMP/EWP/552/95Rev.2. London, CHMP. Nov 2006

Genant HK, Jergas M, Palermo L, Nevitt M, Valentin RS, Black D, Cummings SR (1996) Comparison f semiquantitative visual and quantitative morphometric assessment of prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 11:984–996

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC Jr, Lindsay R (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489

Kanis JA on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group (2008a) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield, UK. Accessible at http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Odén A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX™ and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:385–397

Lu Y, Fuerst T, Hui S, Genant HK (2001) Standardization of bone mineral density at femoral neck, trochanter and Ward's triangle. Osteoporos Int 12:438–444

Breslow NE, Day NE (1987) Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. IARC Scientific Publications No 32 Volume II:p 131-135

Nakano T, Shiraki M, Sugimoto T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Kuroda T, Nakamura T (2013) Once-weekly teriparatide reduces the risk of vertebral fracture in patients with various fracture risks: subgroup analysis of the Teriparatide Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial. J Bone Miner MetabNov 9. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed

McCloskey EV, Spector TD, Eyres KS, Fern ED, O'Rourke N, Vasikaran S, Kanis JA (1993) The assessment of vertebral deformity: a method for use in population studies and clinical trials. Osteoporos Int 3(3):138–147

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is based on an independent investigator-led proposal to Asahi. Asahi did not contribute to analysis nor was funding provided. The authors were granted full access to all data necessary for this work.

Conflicts of interest

NH has received consultancy, lecture fees, and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, AMGEN, MSD, Eli Lilly, Servier, Shire, Consilient Healthcare, and Internis Pharma. JA Kanis has received consulting fees, advisory board fees, lecture fees, and/or grant support from the majority of companies concerned with skeletal metabolism. EVM has received consultancy, lecture fees, research grant support, and/or honoraria from ActiveSignal, Alliance for Better Bone Health, AMGEN, Bayer, Consilient Healthcare, GE Lunar, Hologic, Internis Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Tethys, UCB, and Univadis. TN received research grants and/or consulting fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma, Asahi Kasei Pharma, and Daiichi Sankyo. MS received consulting fees from Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Teijin Pharma, and MSD. TS received consulting fee and/or research grant from Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo-Co., Eli Lilly Japan, and Pfizer. TK is an employee of Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation. Anders Oden and Helena Johansson declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Harvey, N.C., Kanis, J.A., Odén, A. et al. Efficacy of weekly teriparatide does not vary by baseline fracture probability calculated using FRAX. Osteoporos Int 26, 2347–2353 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3129-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3129-7