Abstract

Summary

Addition of 10 mg prednisone daily to a methotrexate-based tight control strategy does not lead to bone loss in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients receiving preventive treatment for osteoporosis. A small increase in lumbar bone mineral density (BMD) during the first year of treatment was recorded, regardless of use of glucocorticoids.

Introduction

This study aims to describe effects on BMD of treatment according to EULAR guidelines with a methotrexate-based tight control strategy including 10 mg prednisone daily versus the same strategy without prednisone in early RA patients who received preventive therapy for osteoporosis.

Methods

Early RA patients were included in the CAMERA-II trial: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind 2-year trial, in which effects of addition of 10 mg prednisone daily to a methotrexate-based tight control strategy were studied. All patients received calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates. Disease activity was assessed every 4 weeks. Radiographs of hands and feet and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry of lumbar spine and left hip were performed at baseline and after 1 and 2 years of treatment.

Results

BMD increased significantly over time in both treatment groups at the lumbar spine with a mean of 2.6 % during the first year (p < 0.001), but not at the hip; at none of the time points did BMD differ significantly between the prednisone and placebo group. Higher age and lower weight at baseline and higher disease activity scores during the trial, but not glucocorticoid therapy, were associated with lower BMD at both the lumbar spine and the hip in mixed-model analyses.

Conclusion

Addition of 10 mg prednisone daily to a methotrexate-based tight control strategy does not lead to bone loss in early RA patients on bisphosphonates. A small increase in lumbar BMD during the first year of treatment was found, regardless of use of glucocorticoids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are frequently used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1]. They are effective in retarding the progression of erosive joint damage in early RA and lead to a faster and better control of disease activity [2–9]. However, the use of these drugs is restrained by the occurrence (and fear) of side effects [10, 11].

According to recent EULAR recommendations on the management of RA, the first step after diagnosis is starting a tight control treatment with methotrexate with or without GCs [12]. Addition of GC therapy to a tight control strategy has many positive effects, which have been shown recently in the CAMERA-II (second Computer-Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis) trial. In this study, the effects of the addition of 10 mg prednisone daily to a tight control methotrexate-based treatment were studied in patients with early RA [13]. Co-treatment with prednisone instead of placebo led to better control of disease activity and to reduced erosive joint damage. The mean dose of methotrexate and the need for biological treatment were decreased. Analyzing the number of patients experiencing at least once a specific adverse event during the study, there were no significant differences, except for less patients in the prednisone group experiencing nausea (p = 0.006), ALAT > upper limit of normal (p = 0.006), and ASAT > upper limit of normal (p = 0.016) compared to patients in the placebo group. Although prophylactic medication for osteoporosis was given, a drawback of the treatment with GCs could be the risk of bone density loss and fractures.

In the first randomized, placebo-controlled study on GC-induced osteoporosis, treatment with slow-acting intramuscular gold salts and 10 mg prednisone daily in the absence of prophylactic medication for osteoporosis led to rapid bone loss in patients with RA, which was partly reversible after discontinuation of prednisone treatment [14]. Caution should be taken in interpreting these data because measurements were performed by dual-energy quantitative computed tomography, which has a relatively low precision. Although the results from other individual studies thereafter with low- to medium-dose GC therapy in RA are inconsistent [3, 6, 15–17], a meta-analysis showed strong correlations between the cumulative GC dose and a decline in bone mineral density (BMD) and between the daily dose and risk of fracture [18].

In RA, bone loss in GC-naive patients may develop; this mainly occurs during the first months of disease [19, 20] and especially in patients with active disease [21–23]. Systemic inflammation, not only via interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) leads to bone loss, but also via decreased weight-bearing physical activity [24], because of pain and stiffness [25]. The impaired mobility also reduces exposure to sunlight which is needed for sufficient amounts of vitamin D, increasing the risk of developing osteoporosis [26, 27] and the risk of falls, leading to fractures. Furthermore, RA patients are mostly women of whom the majority are postmenopausal [25], thus comprising individuals already at high risk of developing osteoporosis. In these circumstances, the negative effects of GCs might be the trigger for definite worsening of the BMD. Although it has been established that preventive medication for osteoporosis (i.e., calcium, vitamin D, bisphosphonates) is effective in inhibiting bone loss and their use is recommended [28], it is also known that adherence to bisphosphonate therapy is low, and this is associated with an increased fracture risk [29]. This makes the fear for development of osteoporosis with chronic prednisone therapy of 10 mg daily in RA patients a realistic concern despite the prescription of preventive therapy.

On the other hand, one could argue that effective therapy could decrease the risk of osteoporosis induced by disease activity. Both treatment strategies in the CAMERA-II trial are treat-to-target strategies aiming at remission, and it might be that the inclusion of prednisone is not as harmful as expected based on earlier reports. The net effects of GCs on bone in RA thus remain controversial: do favorable effects on the inflammatory disease and thus on physical activity outweigh the negative effects on bone (see Fig. 1)?

BMD is influenced by GCs and active RA. Both GC therapy and active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are thought to influence bone mineral density (BMD) in a negative way. However, GCs decrease the disease activity of RA. Therefore, they may exert a positive effect on BMD by lowering inflammation. Actually, the net effect is unknown. BMD bone mineral density, GC glucocorticoid, RA rheumatoid arthritis

In this paper, we describe the effects on bone of adding GC therapy to a tight control strategy in early RA. Primary analyses are focused on BMD changes over time and differences between the prednisone and placebo group. Secondary analyses have been performed to identify the influence of disease characteristics and additional (according to protocol) anti-TNF alpha treatment on BMD.

Methods

CAMERA-II trial

From 2003 until 2008, 236 early RA patients were included in the CAMERA-II trial [13]. This was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multi-center, tight control strategy and treat to target (remission) trial, in which the effects of the addition of 10 mg prednisone daily to a methotrexate-based treatment strategy were studied. All patients were adults who met the 1987 revised American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA with disease duration of less than 1 year. They had not been treated with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs including GCs before. Treatment was started with 10 mg methotrexate weekly. All patients received bisphosphonates (81 % started alendronate; others received risedronate). According to study protocol, calcium supplementation was 500 mg and vitamin D was 400 IE—both usual doses at the time the study was designed. Use of this supplementation was recorded in more than 90 % of patients. Folic acid 0.5 mg daily except for the day of methotrexate intake was also prescribed. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was allowed.

At baseline and every 4 weeks thereafter, the swollen joint count (0–38 joints), tender joint count (0–38 joints), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and visual analog scale (0–100 mm; 100 mm worst) for general well-being were assessed. Treatment was intensified in case patients did not improve sufficiently according to predefined criteria by increasing the methotrexate dosage stepwise, switching to subcutaneous therapy with methotrexate at maximal (tolerated) oral methotrexate dose and as next step adding adalimumab treatment, if needed [13]. If sustained remission (defined as a swollen joint count of 0 and at least two out of the following three: tender joint count ≤3, visual analog scale of well-being ≤20 mm, erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≤20 mm/h (1st), all during at least 3 months) was achieved, methotrexate was reduced gradually by 2.5 mg/week each month as long as remission was present. At baseline and at year 1 and 2, radiographs of hands and feet were taken and scored by two readers according to the Sharp–vanderHeijde score (SHS) [30].

The study was approved by the medical research ethics committees of all centers involved (clinical trial registration number ISRCTN70365169) and had therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent.

BMD measurements

At baseline and after 1 and 2 years of treatment, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was performed. BMD was measured in five centers both at the lumbar spine and left hip, in three centers assessing the total hip, and in two centers assessing the femoral neck. Three centers used Hologic machines (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA), one center used a Lunar machine (General Electric, Madison, WI, USA), and one center used a Norland machine (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, USA). BMD was expressed as grams per square centimeter and T scores were given. A patient is defined as having a normal BMD with T scores of −1 or above at both lumbar spine and hip [31]. Patients with T scores between −1 and −2.5 at lumbar spine and/or hip are qualified as osteopenic [31]. A T score of −2.5 or below at lumbar spine and/or hip indicated osteoporosis [31].

Statistical analyses

The BMD values derived from the different machines and different regions of the hip were calculated to standardized BMD (sBMD) values with previously reported and validated formulas [32, 33]. Differences between the two groups in means of continuous data were tested with independent-samples t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests, where appropriate, and differences in categorical data with chi-square tests.

Differences in sBMD values between the two groups over time were tested using repeated-measures ANOVA. Additionally, longitudinal regression analyses (mixed models) were performed to assess the influence of patient characteristics and disease severity on the course of sBMD. A random intercept was used, and treatment group and time were independent variables, and sBMD in the lumbar spine or left hip (with separate analyses for these two variables) was the dependent variable. Gender, age, weight, rheumatoid factor status, baseline DAS28 (disease activity score based on 28 joints), and average DAS28 during the trial period were used as covariates in the models. Several interaction terms (i.e., treatment strategy × gender, treatment strategy × age, treatment strategy × time, age × time) were also tested in the models to investigate whether the effect of the treatment strategy on sBMD was constant between subgroups and whether the effects of the treatment strategy and age on BMD were constant over time. Using a backward selection strategy, variables which did not contribute to the model were removed from the model one by one. A liberal p-value (p > 0.20) was used for exclusion from the model. In all models, treatment strategy and study center were retained as covariates. Separate models were created including SHS instead of DAS28 measurements or including adalimumab treatment. Since mixed model analyses can account for missing data (assumed to be missing at random), patients who missed one or two BMD measurements were still included in the longitudinal regression analyses.

The statistical software SPSS 18.0 and NCSS 2007 were used for analyses of data. Unless stated otherwise, P values below 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1 for the complete trial population and the group with at least one BMD measurement during the trial. DXA scans at 0, 1, and 2 years were performed in respectively 73, 63, and 61 % of the patients. The prednisone and placebo strategy group in the current analyses did not differ significantly from the original study groups for any of the baseline variables. The two groups included in the current analyses only differed from each other at baseline in the number of patients with rheumatoid factor and the mean DAS28.

BMD measurements

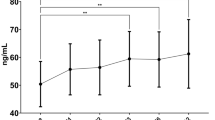

The mean sBMD levels for each treatment group at specific time points are shown in Fig. 2. The sBMD increased significantly over the first year of treatment in both treatment groups in the lumbar spine (paired samples t-test with sBMD at 0 and 1 year, p < 0.001 for the prednisone group and the placebo group), with a mean increase in sBMD of 2.7 % in the prednisone group and 2.4 % in the placebo group. During the second year of treatment, the BMD in the prednisone group showed a small decrease to 2.4 % above baseline values (not significant), while in the placebo group the BMD rose significantly to 3.4 % above baseline values (p = 0.01). The sBMD in the left hip did not change significantly during the 2 years of treatment.

sBMD in lumbar spine and left hip over time. This figure shows the sBMD during the trial for the prednisone (solid lines) and placebo (dashed lines) group. BMD values measured in lumbar spine and left hip (total hip or femoral neck) were recalculated to sBMD values with previously reported and validated formulas [32, 33]. The figures include all sBMD values of patients who had BMD measurements at all time points. Means and SD are depicted. BMD bone mineral density, sBMD standardized bone mineral density

Repeated-measures ANOVA also showed a significant increase over 2 years’ time in the lumbar spine (F = 27.488, p < 0.001). Significant differences between the treatment strategies in sBMD or the trend over time could not be demonstrated. In general, the trend over time in sBMD was similar for men and women, although the effect size was somewhat larger in women (not significantly).

Influence of patient characteristics and disease severity

Longitudinal regression analyses (mixed models) were performed to assess the influence of patient characteristics and disease severity on the course of sBMD levels (see Tables 2 and 3). Higher age and lower weight at baseline were associated with lower sBMD in the lumbar spine as well as in the hip. The sBMD values at the hip were significantly higher in male patients. The treatment strategy was not significantly related to sBMD levels. Treatment with prednisone at a higher age even resulted in a positive influence on the sBMD of the hip (see age × treatment with prednisone term in Table 3).

Furthermore, disease severity was of influence, reflected by the negative influence on sBMD of higher DAS28 (included in the model as area under the curve of all DAS28 measurements during the complete trial period) for the lumbar spine and hip. A rheumatoid factor positive status did negatively influence the sBMD at the lumbar spine, but not at the hip. If the model for lumbar sBMD was created without the variable “rheumatoid factor,” the model included 170 instead of 145 patients (72 % instead of 61 % of the original trial population). In that case, age and weight were still significantly associated with lumbar sBMD values, but the influence of DAS28 during the trial was just not significant anymore.

If the mixed models were created with baseline SHS and progression of SHS during the trial instead of DAS28 measurements, a significant influence of progression of SHS was found (beta −0.007, 95 % CI of beta −0.014 to −0.001, p = 0.03) at the lumbar spine, but not at the hip.

Anti-TNF alpha treatment

During the trial, in 58 patients, adalimumab was added to the strategy during the trial as protocolized strategy step because of insufficient response to treatment with methotrexate and prednisone or placebo. DXA scans at 0, 1, and 2 years were performed in respectively 76, 84 and 71 % of these patients. Of the patients who needed adalimumab, only 16 (28 %) had been treated with prednisone. Patients who needed adalimumab co-therapy had a significantly lower baseline sBMD at the hip (mean 0.89 ± 0.14 SD versus mean 0.94 ± 0.15 SD, p = 0.04) but not at the lumbar spine.

When we included the number of adalimumab injections into the models, we found a positive impact of the number of adalimumab injections on sBMD in the lumbar spine (beta 0.003, 95 % CI of beta 0.000 to 0.006, p = 0.03), while the influences of other variables stayed unchanged. At the hip, the number of adalimumab injections was associated with a decrease in sBMD (beta −0.003, 95 % CI of beta −0.004 to −0.001, p < 0.01), while the influence of gender was not significant anymore.

Discussion

In this paper, we describe that addition from start of therapy of 10 mg prednisone daily to a methotrexate-based tight control strategy does not lead to bone loss in early RA patients treated with osteoporosis-preventive drugs. In fact, there is an increase in BMD during the first year of treatment regardless of the use of GCs.

Our findings of a minimal impact of GCs on bone and the absence of significant differences between GC and placebo group are in line with results of several earlier studies on BMD in early RA [3, 6, 16, 17, 34]. There were small increases in lumbar sBMD in both the GC and placebo groups, possibly reflecting the effective dampening of the inflammatory process in early RA, especially of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF. These have direct effects on osteoclast formation and stimulate osteoblasts and T lymphocytes to produce receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B (RANK) ligand, leading to differentiation and activation of osteoclasts [35–37].

To this increase in lumbar sBMD, the bone protective medication prescribed in all our patients probably will also have contributed. The changes in BMD in our study are comparable to changes encountered in other studies on the effectiveness of alendronate in GC-induced osteoporosis in patients with RA and other inflammatory rheumatic diseases who also received calcium tablets [38, 39]. Again, effects were strongest on BMD of the lumbar spine [38]. In recent guidelines, the use of bisphosphonates is recommended with chronic prednisone use in dosages above 7.5 mg daily in postmenopausal women and in men with age above 70 years [40, 41]. In premenopausal women and men with age below 70 years, it is advised that additional BMD measurements be performed to assess the need for bisphosphonates [40, 41]. This implicates that in our study some patients might have not needed the osteoporosis preventive medication. Nevertheless, with ongoing inflammation and decrease in physical activity, patients with RA are at a higher risk for developing osteoporosis, and early intervention including bisphosphonates can be advocated.

This study revealed an influence of inflammation on BMD. In the mixed model analyses, the DAS28 measurements during the trial had a negative impact on BMD of both lumbar spine and hip. This indicates that in active early RA the benefits of GC therapy on the dampening of inflammation outweigh the risk of developing osteoporosis if preventive measures for osteoporosis have been taken. It is unclear whether the positive effects on BMD also lead to a reduction of the fracture risk since an increased risk of fracture has been observed with the same BMD level in GC users compared to non-GC users [42]. This suggests that bone structure negatively influenced by GCs might also play a role.

A subgroup of patients with active disease who responded insufficiently to treatment with methotrexate and prednisone or placebo started anti-TNF alpha treatment with adalimumab added to medication. The number of subcutaneous adalimumab injections was positively associated with lumbar sBMD and negatively with hip sBMD in our study. Because this study had not been designed to assess the effects of adalimumab and the number of patients starting adalimumab was relatively small, no conclusions can be drawn on the effects of anti-TNF medication on BMD.

The results of this study indicate that the use of 10 mg prednisone in early RA following recent recommendations should not be restricted by fears of GC-induced osteoporosis if effective preventive measures are taken. Interestingly, the increase in sBMD is mainly achieved during the first year of treatment, while in the second year of treatment this increase diminishes. This is in line with earlier studies on effects of bisphosphonates on GC-induced osteoporosis [38, 39]. Based on this study, it is impossible to predict the effects on sBMD if GCs are used for more than 2 years and to speculate about a safe duration of GC treatment. The stagnation of BMD increase during the second year of treatment might indicate that GCs are not harmful during the first period of active disease but that GC treatment can still have harmful effects during treatment of longer duration. In that case, it can be advocated to recommend tapering and stopping GC therapy as soon as possible after 2 years of treatment, also because joint sparing properties have not been proven for treatment duration of more than 2 years. Another reason for the stagnation of BMD increase could be decreasing rates of adherence to bisphosphonates. The adherence has not been assessed in this trial, but a recent meta-analysis showed a suboptimal adherence with a pooled mean medication possession ratio of 67 % [43]. It is possible that suboptimal bisphosphonate intake in this trial has limited positive effects of bisphosphonates.

Our study has limitations. First, we had to recalculate sBMD values because of the different DXA machines used at the different hospitals and the different sites of the left hip measured. Fortunately, frequently used and validated formulas for calculating “standardized” BMD values were available and could be applied in this study [32, 33]. Moreover, in the mixed models, study center was included as a covariate, providing an additional correction for the different DXA machines and the (clinical) measurements in different study centers. Second, not all patients underwent DXA measurements, but more than three quarters had at least one measurement and could be included in the mixed model analyses, assuming that missing data are missing at random. The placebo group also received preventive therapy for osteoporosis, and due to this design, direct comparison with GC-naive RA patients not using this prophylactic medication is not possible. Possibly, GC-naive patients without osteoporosis preventive treatment would lose instead of increase bone in BMD. In that case, the difference in BMD between patients on GC treatment combined with preventive therapy for osteoporosis on one hand, and GC-naive patients on the other hand, would be larger than that found in this study.

In conclusion, addition of 10 mg prednisone daily from start of therapy to a methotrexate-based tight control strategy does not lead to bone loss in early RA patients receiving preventive treatment for osteoporosis. In fact, a small increase in BMD of the lumbar spine during the first year of treatment was recorded, regardless of the use of GCs.

References

Sokka T, Toloza S, Cutolo M, Kautiainen H, Makinen H, Gogus F, Skakic V, Badsha H, Peets T, Baranauskaite A, Geher P, Ujfalussy I, Skopouli FN, Mavrommati M, Alten R, Pohl C, Sibilia J, Stancati A, Salaffi F, Romanowski W, Zarowny-Wierzbinska D, Henrohn D, Bresnihan B, Minnock P, Knudsen LS, Jacobs JW, Calvo-Alen J, Lazovskis J, Pinheiro Gda R, Karateev D, Andersone D, Rexhepi S, Yazici Y, Pincus T (2009) Women, men, and rheumatoid arthritis: analyses of disease activity, disease characteristics, and treatments in the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther 11(1):R7

Kirwan JR (1995) The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. The Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low-Dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. N Engl J Med 333(3):142–146

Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, van de Laar MA, Westhovens R, van Denderen JC, van Zeben D, Dijkmans BA, Peeters AJ, Jacobs P, van den Brink HR, Schouten HJ, van der Heijde DM, Boonen A, van der Linden S (1997) Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 350(9074):309–318

van Everdingen AA, Jacobs JW, Siewertsz Van Reesema DR, Bijlsma JW (2002) Low-dose prednisone therapy for patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis: clinical efficacy, disease-modifying properties, and side effects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 136(1):1–12

Wassenberg S, Rau R, Steinfeld P, Zeidler H (2005) Very low-dose prednisolone in early rheumatoid arthritis retards radiographic progression over two years: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 52(11):3371–3380

Svensson B, Boonen A, Albertsson K, van der Heijde D, Keller C, Hafstrom I (2005) Low-dose prednisolone in addition to the initial disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis reduces joint destruction and increases the remission rate: a two-year randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum 52(11):3360–3370

Kirwan JR, Bijlsma JW, Boers M, Shea BJ (2007) Effects of glucocorticoids on radiological progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD006356

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, Peeters AJ, de Jonge-Bok JM, Mallee C, de Beus WM, de Sonnaville PB, Ewals JA, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA (2007) Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 146(6):406–415

Choy EH, Smith CM, Farewell V, Walker D, Hassell A, Chau L, Scott DL (2008) Factorial randomised controlled trial of glucocorticoids and combination disease modifying drugs in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 67(5):656–663

van Tuyl LH, Plass AM, Lems WF, Voskuyl AE, Dijkmans BA, Boers M (2007) Why are Dutch rheumatologists reluctant to use the COBRA treatment strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 66(7):974–976

van der Goes MC, Jacobs JW, Boers M, Andrews T, Blom-Bakkers MA, Buttgereit F, Caeyers N, Choy EH, Cutolo M, Da Silva JA, Guillevin L, Holland M, Kirwan JR, Rovensky J, Saag KG, Severijns G, Webber S, Westhovens R, Bijlsma JW (2010) Patient and rheumatologist perspectives on glucocorticoids: an exercise to improve the implementation of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 69(6):1015–1021

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gorter S, Knevel R, Nam J, Schoels M, Aletaha D, Buch M, Gossec L, Huizinga T, Bijlsma JW, Burmester G, Combe B, Cutolo M, Gabay C, Gomez-Reino J, Kouloumas M, Kvien TK, Martin-Mola E, McInnes I, Pavelka K, van Riel P, Scholte M, Scott DL, Sokka T, Valesini G, van Vollenhoven R, Winthrop KL, Wong J, Zink A, van der Heijde D (2010) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 69(6):964–975

Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Welsing PM, Verstappen SM, Tekstra J, Ton E, Geurts MA, van der Werf JH, van Albada-Kuipers GA, Jahangier-de Veen ZN, van der Veen MJ, Verhoef CM, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW (2012) Low-dose prednisone inclusion in a methotrexate-based, tight control strategy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 156(5):329–339

Laan RF, van Riel PL, van de Putte LB, van Erning LJ, van't Hof MA, Lemmens JA (1993) Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med 119(10):963–968

Hansen M, Podenphant J, Florescu A, Stoltenberg M, Borch A, Kluger E, Sorensen SF, Hansen TM (1999) A randomised trial of differentiated prednisolone treatment in active rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical benefits and skeletal side effects. Ann Rheum Dis 58(11):713–718

van Everdingen AA, Siewertsz van Reesema DR, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW (2003) Low-dose glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis: discordant effects on bone mineral density and fractures? Clin Exp Rheumatol 21(2):155–160

Capell HA, Madhok R, Hunter JA, Porter D, Morrison E, Larkin J, Thomson EA, Hampson R, Poon FW (2004) Lack of radiological and clinical benefit over two years of low dose prednisolone for rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 63(7):797–803

van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C (2002) The epidemiology of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 13(10):777–787

Shenstone BD, Mahmoud A, Woodward R, Elvins D, Palmer R, Ring EF, Bhalla AK (1994) Longitudinal bone mineral density changes in early rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 33(6):541–545

Keller C, Hafstrom I, Svensson B (2001) Bone mineral density in women and men with early rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 30(4):213–220

Gough AK, Lilley J, Eyre S, Holder RL, Emery P (1994) Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 344(8914):23–27

Forslind K, Keller C, Svensson B, Hafstrom I (2003) Reduced bone mineral density in early rheumatoid arthritis is associated with radiological joint damage at baseline and after 2 years in women. J Rheumatol 30(12):2590–2596

Book C, Karlsson M, Akesson K, Jacobsson L (2008) Disease activity and disability but probably not glucocorticoid treatment predicts loss in bone mineral density in women with early rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 37(4):248–254

Sokka T, Hakkinen A, Kautiainen H, Maillefert JF, Toloza S, Mork Hansen T, Calvo-Alen J, Oding R, Liveborn M, Huisman M, Alten R, Pohl C, Cutolo M, Immonen K, Woolf A, Murphy E, Sheehy C, Quirke E, Celik S, Yazici Y, Tlustochowicz W, Kapolka D, Skakic V, Rojkovich B, Muller R, Stropuviene S, Andersone D, Drosos AA, Lazovskis J, Pincus T (2008) Physical inactivity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from twenty-one countries in a cross-sectional, international study. Arthritis Rheum 59(1):42–50

Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW (2010) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 376(9746):1094–1108

Ernst E (1998) Exercise for female osteoporosis. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Sports Med 25(6):359–368

Karkkainen M, Rikkonen T, Kroger H, Sirola J, Tuppurainen M, Salovaara K, Arokoski J, Jurvelin J, Honkanen R, Alhava E (2009) Physical tests for patient selection for bone mineral density measurements in postmenopausal women. Bone 44(4):660–665

Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK, Deal C, Caplan L, Chen W, Curtis JR, Furst DE, McMahon M, Patkar NM, Volkmann E, Saag KG (2010) American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62(11):1515–1526

Wade SW, Curtis JR, Yu J, White J, Stolshek BS, Merinar C, Balasubramanian A, Kallich JD, Adams JL, Viswanathan HN (2012) Medication adherence and fracture risk among patients on bisphosphonate therapy in a large United States health plan. Bone 50:870–875

van der Heijde DM, van Riel PL, Nuver-Zwart IH, Gribnau FW, vad de Putte LB (1989) Effects of hydroxychloroquine and sulphasalazine on progression of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1(8646):1036–1038

Kanis JA (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group Osteoporos Int 4(6):368–381

Hui SL, Gao S, Zhou XH, Johnston CC Jr, Lu Y, Gluer CC, Grampp S, Genant H (1997) Universal standardization of bone density measurements: a method with optimal properties for calibration among several instruments. J Bone Miner Res 12(9):1463–1470

Lu Y, Fuerst T, Hui S, Genant HK (2001) Standardization of bone mineral density at femoral neck, trochanter and Ward's triangle. Osteoporos Int 12(6):438–444

Ibanez M, Ortiz AM, Castrejon I, Garcia-Vadillo JA, Carvajal I, Castaneda S, Gonzalez-Alvaro I (2010) A rational use of glucocorticoids in patients with early arthritis has a minimal impact on bone mass. Arthritis Res Ther 12(2):R50

Bezerra MC, Carvalho JF, Prokopowitsch AS, Pereira RM (2005) RANK, RANKL and osteoprotegerin in arthritic bone loss. Braz J Med Biol Res 38(2):161–170

Mabilleau G, Pascaretti-Grizon F, Basle MF, Chappard D (2012) Depth and volume of resorption induced by osteoclasts generated in the presence of RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1 or LIGHT. Cytokine 57(2):294–299

The Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation on Clinical Trials of Cortisone, A.C.T.H., and Other Therapeutic Measures in Chronic Rheumatic Diseases (1954) A comparison of cortisone and aspirin in the treatment of early cases of rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J 1(4873):1223–1227

de Nijs RN, Jacobs JW, Lems WF, Laan RF, Algra A, Huisman AM, Buskens E, de Laet CE, Oostveen AC, Geusens PP, Bruyn GA, Dijkmans BA, Bijlsma JW (2006) Alendronate or alfacalcidol in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 355(7):675–684

Lems WF, Lodder MC, Lips P, Bijlsma JW, Geusens P, Schrameijer N, van de Ven CM, Dijkmans BA (2006) Positive effect of alendronate on bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on chronic treatment with low-dose prednisone: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 17(5):716–723

Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Boers M, Boumpas D, Buttgereit F, Caeyers N, Choy EH, Cutolo M, Da Silva JA, Esselens G, Guillevin L, Hafstrom I, Kirwan JR, Rovensky J, Russell A, Saag KG, Svensson B, Westhovens R, Zeidler H, Bijlsma JW (2007) EULAR evidence-based recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 66(12):1560–1567

CBO (2011) Guideline for osteoporosis and fracture prevention, third revision. [Richtlijn Osteoporose en fractuurpreventie, derde herziening]. http://www.cbo.nl/Downloads/1385/OsteoporoseRichtlijn%202011.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2012

Van Staa TP, Laan RF, Barton IP, Cohen S, Reid DM, Cooper C (2003) Bone density threshold and other predictors of vertebral fracture in patients receiving oral glucocorticoid therapy. Arthritis Rheum 48(11):3224–3229

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21(11):1943–1951

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating research nurses of the Utrecht Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort study group for data collection, A.W.J.M. Jacobs-van Bree for data entry, S.M. Sijbers-Klaver for data management, and A.A. van Everdingen, MD, PhD, for scoring radiographs.

Funding

The CAMERA-II study was financially supported by an unrestricted grant of the Dutch funding organization ‘Catharijne Stichting’.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommrcial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Goes, M.C., Jacobs, J.W.G., Jurgens, M.S. et al. Are changes in bone mineral density different between groups of early rheumatoid arthritis patients treated according to a tight control strategy with or without prednisone if osteoporosis prophylaxis is applied?. Osteoporos Int 24, 1429–1436 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2073-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2073-z