Abstract

Summary

This analysis compares femur neck bone mineral density (FNBMD) and bone determinants in adults between National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III (1988–1994) and NHANES 2005–2008. FNBMD was higher in NHANES 2005–2008 than in NHANES III, but between-survey differences varied by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. The likelihood that FNBMD has improved appears strongest for older white women.

Introduction

Recent data on hip fracture incidence and femur neck osteoporosis suggest that the skeletal status of older US adults has improved since the 1990s, but the explanation for these changes remains uncertain.

Methods

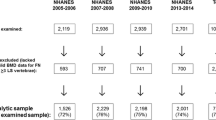

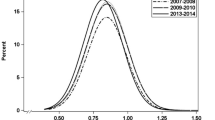

The present study compares mean FNBMD of adults ages 20 years and older between the third (NHANES III, 1988–1994) and NHANES 2005–2008. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry systems (pencil beam in NHANES III, fan beam in NHANES 2005–2008) were used to measure hip BMD, and several bone determinants are compared between surveys to assess their potential role in explaining observed FNBMD differences.

Results

FNBMD was higher overall in NHANES 2005–2008 than in NHANES III, but between-survey differences varied by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Although FNBMD differences in several groups were small enough (≤3%) to be attributable to use of different dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) systems in the two surveys, variability in size and direction of the differences does not support artifactual differences in DXA methodology as the sole explanation. Several FNBMD determinants (body size, smoking, selected bone-active medications, self-reported health status, calcium intake, and caffeine consumption) changed in a bone-improving direction in older adults, but FNBMD in older non-Hispanic white women remained significantly higher in 2005–2008 even after adjusting for DXA methodology or for the selected bone determinants.

Conclusion

The likelihood that FNBMD has improved appears strongest for older white women, but the reason for the improvement in this group remains unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Looker AC, Melton LJ 3rd, Borrud Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA (2010) Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005–2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 25:64–71

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 302:1573–1579

Gehlbach SH, Avrunin JS, Puleo E (2007) Trends in hospital care for hip fractures. Osteoporos Int 18:585–591

Melton LJ 3rd, Kearns AE, Atkinson EJ, Bolander ME, Achenbach SJ, Huddleston JM, Therneau TM, Leibson CL (2009) Secular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrence. Osteoporos Int 20:687–694

Nieves JW, Bilezikian JP, Lane JM, Einhorn TA, Wang Y, Steinbuch M, Cosman F (2010) Fragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristics. Osteoporos Int 21:399–408

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ 3rd, Khaltaev N (2008) A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone 42:467–475

Reid IR (2008) Relationships between fat and bone. Osteoporos Int 19:595–606

MacLean C, Alexander A, Carter J, Chen S, Desai SB, Grossman J, Maglione M, McNamara M, Mojica W, Newberry S, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Timmer M, Tringate C, Valentine D, Zhou A. Comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 12. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, December 2007

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL (2002) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 288:1723–1727

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM (2006) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 295:1549–1555

Stafford RS, Drieling RL, Hersh AL (2004) National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988–2003. Arch Intern Med 164:1525–1530

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (1999) Current National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/currentnhanes.htm. Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010

National Center for Health Statistics (1994) Plan and operation of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Vital Health Stat 1(32). DHHS Publ No. (PHS) 94–1308. NCHS, Hyattsville, MD. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3. Accessed on 23 Nov 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2007) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) procedure manual. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_dexa.pdf. Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010

Wahner HW, Looker AC, Dunn WL, Walters LC, Hauser MF, Novak C (1994) Quality control of bone densitometry in a national health survey (NHANES III) using three mobile examination centers. J Bone Miner Res 9:951–960

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2008) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, D. C., pp 1–36

Kanis J (2008) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. In Group WHOS (ed). WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Analytic and reporting guidelines. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). September, 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/nhanes_analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf. Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010

Bouyoucef SE, Cullum ID, Ell PJ (1996) Cross-calibration of a fan-beam X-ray densitometer with a pencil-beam system. Br J Radiol 69:522–531

Barthe N, Braillon P, Ducassou D, Basse-Cathalinat B (1997) Comparison of two Hologic DXA systems (QDR 1000 and QDR 4500/A). Br J Radiol 70:728–739

Kolta S, Ravaud P, Fechtenbaum J, Dougados M, Roux C (2000) Follow-up of individual patients on two DXA scanners of the same manufacturer. Osteoporos Int 11:709–713

Henzell S, Dhaliwal SS, Price RI, Gill F, Ventouras C, Green C, Da Fonseca F, Holzherr M, Prince R (2003) Comparison of pencil-beam and fan-beam DXA systems. J Clin Densitom 6:205–210

Cummings SR, Cawthon P, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Fink HA, Orwoll ES (2006) BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res 21:1550–1556

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2009: With special feature on medical technology. Hyattsville MD. 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus09.pdf. Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010)

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Mean body weight, height and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Advance Data from Vital and health Statistics No. 347. October 27, 2004. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad347.pdf Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010

Briefel RR, Johnson CL (2004) Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr 24:401–431

O’Neill TW, Grazio S, Spector TD, Silman AJ (1996) Geometric measurements of the proximal femur in UK women: secular increase between the late 1950s and early 1990s. Osteoporos Int 6:136–140

Reid IR, Chin K, Evans MC, Jones JG (1994) Relation between increase in length of hip axis in older women between 1950s and 1990s and increase in age specific rates of hip fracture. BMJ 309:508–509

Guglielmi G, van Kuijk C, Li J, Meta MD, Scillitani A, Lang TF (2006) Influence of anthropometric parameters and bone size on bone mineral density using volumetric quantitative computed tomography and dual X-ray absorptiometry at the hip. Acta Radiol 47:574–580

Lochmüller EM, Miller P, Bürklein D, Wehr U, Rambeck W, Eckstein F (2000) In situ femoral dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry related to ash weight, bone size and density, and its relationship with mechanical failure loads of the proximal femur. Osteoporos Int 11:361–367

US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Healthy People 2010 Progress Review. Physical Activity and Fitness. June 26, 2008. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Data/2010prog/focus22/2008Focus22.pdf. Accessed on: 23 Nov 2010

Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ, Buie VC, Chander J, Hawkes W, Martin A, Holder L, Hebel JR, Sloane PD, Magaziner J (1999) The prevalence of osteoporosis in nursing home residents. Osteoporos Int 9:151–157

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Specific drugs composing medication groups

-

I.

Medications that increase BMD

-

(A)

Sex hormones (NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2008)

-

1.

Estrogens: estradiol, estradiol valerate, estrogenic substances, conjugated estrogens, esterified estrogens (alone and with methyltestosterone), estropipate, ethinyl estradiol (alone or with ethynodiol diacetate, levonorgestrel, norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, or desogestrel), diethylstilbesterol (alone or with disphosphate), fluoxymesterone, or quinestrol.

-

2.

Testosterones: testosterone, testosterone cypionate, stanozolol and nandrolone decanoate.

-

1.

-

(B)

Non-estrogen drugs

-

1.

NHANES III: calcitonin, calcitriol, ergocalciferol, etidronate, sodium fluoride, tamoxifen, and calcium acetate.

-

2.

NHANES 2005–2008: bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, etidronate, pamidronate, tiludronate, ibandronate, zolendronate), calcitonin, calcitriol, fluoride, raloxifene, tamoxifen, tibolone, strontium ranelate, parathyroid hormone, and teriparatide.

-

1.

-

(A)

-

II.

Medications that decrease BMD (NHANES III and NHANES 2005–2008)

-

1.

Glucocorticoids: betamethasone, budesonide, cortisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methlprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone, and triamcinolone.

-

2.

Antineoplastic drugs: anastrozole, bicalutamide, capecitabine, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, erlotinib, estramustine, exemestane, fluorouracil, fluoxymesterone, flutamide, goserelin, hydroxyurea, interferon alfa 2A and 2B, irinotecan, isotretinoin, letrozole, leuprolide, levamisole, lomustine, medroxyprogesterone, megestrol, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, nilutamide, tegafur or uracil, tretinoin, and unspecified antineoplastics.

-

3.

Anticonvulsants: carbamazepine, clonazepam, diazepam, divalproex sodium, ethosuximide, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, lorazepam, mephobarbital, methsuximide, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, primidone, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide.

-

4.

Barbiturates: butabarbital, butalbital

-

5.

Anticoagulants: heparin and enoxaparin.

-

6.

IV nutrition products: LVP solution with potassium

-

1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Looker, A.C., Melton, L.J., Borrud, L.G. et al. Changes in femur neck bone density in US adults between 1988–1994 and 2005–2008: demographic patterns and possible determinants. Osteoporos Int 23, 771–780 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1623-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1623-0