Abstract

Summary

Persistence with osteoporosis therapy remains low and identification of factors associated with better persistence is essential in preventing osteoporosis and fractures. In this study, patient understanding of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) results and beliefs in effects of treatment were associated with treatment initiation and persistence.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to examine patient understanding of their DXA results and evaluate factors associated with initiation of and persistence with prescribed medication in first-time users of anti-osteoporotic agents. Self-reported DXA results reflect patient understanding of diagnosis and may influence acceptance of osteoporosis therapy. To improve patient understanding of DXA results, we provided written information to patients and their referring general practitioner (GP), and evaluated factors associated with osteoporosis treatment initiation and 1-year persistence.

Methods

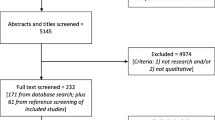

Information on diagnosis was mailed to 1,000 consecutive patients and their GPs after DXA testing. One year after, a questionnaire was mailed to all patients to evaluate self-report of DXA results, drug initiation and 1-year persistence. Quadratic weighted kappa was used to estimate agreement between self-report and actual DXA results. Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate predictors of understanding of diagnosis, and correlates of treatment initiation and persistence.

Results

A total of 717 patients responded (72%). Overall, only 4% were unaware of DXA results. Agreement between self-reported and actual DXA results was very good (κ = 0.83); younger age and glucocorticoid use were associated with better understanding. Correctly reported DXA results was associated with treatment initiation (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.2–15.1, p = 0.02), and greater beliefs in drug treatment benefits were associated with treatment initiation (OR 1.4, 95%CI 1.1–1.9, p = 0.006) and persistence with therapy (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.7, p = 0.006).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that written information provides over 80% of patients with a basic understanding of their DXA results. Communicating results in writing may improve patient understanding thereby also improve osteoporosis management and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cooper A (2006) Compliance with treatment for osteoporosis. Lancet 368:1648

Cramer JA, Silverman S (2006) Persistence with bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis: finding the root of the problem. Am J Med 119:S12–S17

Payer J, Killinger Z, Ivana S, Celec P (2007) Therapeutic adherence to bisphosphonates. Biomed Pharmacother 61:191–193

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V et al (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19(6):811–818

Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgstrom F, Herings RM, Silverman SL (2009) Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med 122:S3–S13

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Gold DT, Alexander IM, Ettinger MP (2006) How can osteoporosis patients benefit more from their therapy? Adherence issues with bisphosphonate therapy. Ann Pharmacother 40:1143–1150

Moller PK (2003) Pricing and reimbursement of drugs in Denmark. Eur J Health Econ 4:60–65

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int 16:134–141

Jaglal SB, Cameron C, Hawker GA et al (2006) Development of an integrated-care delivery model for post-fracture care in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int 17:1337–1345

Haussler B, Gothe H, Gol D, Glaeske G, Pientka L, Felsenberg D (2007) Epidemiology, treatment and costs of osteoporosis in Germany—the BoneEVA Study. Osteoporos Int 18:77–84

Lekkerkerker F, Kanis JA, Alsayed N et al (2007) Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis: a need for study. Osteoporos Int 18:1311–1317

Cadarette SM, Beaton DE, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Dickson L, Hawker GA (2007) Minimal error in self-report of having had DXA, but self-report of its results was poor. J Clin Epidemiol 60:1306–1311

Pickney CS, Arnason JA (2005) Correlation between patient recall of bone densitometry results and subsequent treatment adherence. Osteoporos Int 16:1156–1160

Fitt NS, Mitchell SL, Cranney A, Gulenchyn K, Huang M, Tugwell P (2001) Influence of bone densitometry results on the treatment of osteoporosis. CMAJ 164:777–781

Cadarette SM, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Beaton DE, Hawker GA (2007) Access to osteoporosis treatment is critically linked to access to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry testing. Med Care 45:896–901

Lægemiddelstyrelsen (2003) Kriterier for enkelttilskud til Ebixa, kolinesterasehæmmere, osteoporosemidler, Plavix og Persantin. Ugeskr Læger;2845

WHO Study Group (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 843:1–129

Cadarette SM, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Beaton DE, Hawker GA (2009) Measuring patient perceptions about osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. BMC Res Notes 2:133

Byrt T (1996) How good is that agreement? Epidemiology 7:561

Pressman A, Forsyth B, Ettinger B, Tosteson AN (2001) Initiation of osteoporosis treatment after bone mineral density testing. Osteoporos Int 12:337–342

Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Hammond CS et al (2003) Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med 115:209–216

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ et al (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Kilding R, Eastell R, Peel N (2002) Do patients receive appropriate information and treatment following bone mineral density measurements? Rheumatol (Oxf) 41:1073–1074

Weiss TW, Siris ES, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, McHorney CA (2007) Osteoporosis practice patterns in 2006 among primary care physicians participating in the NORA study. Osteoporos Int 18(11):1473–1480

Chenot R, Scheidt-Nave C, Gabler S, Kochen MM, Himmel W (2007) German primary care doctors' awareness of osteoporosis and knowledge of national guidelines. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 115:584–589

Jaglal SB, Carroll J, Hawker G et al (2003) How are family physicians managing osteoporosis? Qualitative study of their experiences and educational needs. Can Fam Physician 49:462–468

Campbell MK, Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, McClure JD, Reid DM (1998) Direct disclosure of bone density results to patients: effect on knowledge of osteoporosis risk and anxiety level. Osteoporos Int 8:584–590

Stock JL, Waud CE, Coderre JA et al (1998) Clinical reporting to primary care physicians leads to increased use and understanding of bone densitometry and affects the management of osteoporosis. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 128:996–999

Nielsen D, Ryg J, Nielsen W, Knold B, Nissen N, Brixen K (2010) Patient education in groups increases knowledge of osteoporosis and adherence to treatment: a two-year randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns (in press)

Horne R, Weinman J (1999) Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res 47:555–567

Lau E, Papaioannou A, Dolovich L et al (2008) Patients' adherence to osteoporosis therapy: exploring the perceptions of postmenopausal women. Can Fam Physician 54:394–402

Switzer JA, Jaglal S, Bogoch ER (2009) Overcoming barriers to osteoporosis care in vulnerable elderly patients with hip fractures. J Orthop Trauma 23:454–459

Tosteson AN, Do TP, Wade SW, Anthony MS, Downs RW (2010) Persistence and switching patterns among women with varied osteoporosis medication histories: 12-month results from POSSIBLE US. Osteoporos Int (in press)

Warriner AH, Curtis JR (2009) Adherence to osteoporosis treatments: room for improvement. Curr Opin Rheumatol 21:356–362

Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ (2006) Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928

Acknowledgments

Dr. Cadarette holds a New Investigator Award in the Area of Aging and Osteoporosis from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Example of personalized letter sent to patients and physicians regarding DXA test results. The original letters were written in Danish, and thus this is an example only based on a translation into English

Ms XX

Examination Date 12-05-2010

Your DXA bone density examination shows the following

The scan shows osteoporosis. (Other diseases such as lack of vitamin D can give rise to a similar result).

According to the information given to us, your risk factors for osteoporosis were the following

Smoking.

Comments to you from the doctor

The bone density is reduced to a degree corresponding to osteoporosis (bone fragility). Your risk of suffering a bone fracture within the next 10 years was estimated to about 10%, based on your DXA result, age, and sex. The risk of fractures can be reduced through medical treatment for osteoporosis. I recommend that you consult your GP for advice on this. In addition, smoking reduces bone mass and increases your risk of a fracture. In my opinion, the DXA scan should be repeated in 2 years.

Osteoporosis (bone fragility) is a loss of bone tissue and bone mineral, which leads to increased risk of broken bones after minor loads or falls. It is important to show due consideration and avoid lifting heavy burdens or bending the back while lifting. Preventing falls is important, particularly in the elderly. If you are working, you should seek advice from your doctor regarding how much lifting could be considered safe and whether some forms of work should not be undertaken. Medical treatment is possible in every case.

Detailed information about the DXA examination

You can find the detailed results below. The numbers are particularly important when you seek advice from health professionals, e.g., your GP.

T-score is a measure of whether one has osteoporosis. A more negative number indicates a lower bone density. Scores below −2.5 define osteoporosis.

Z-score is a measure of bone density compared with that of others of the same sex and age.

A positive number indicates that your bone density is above average—a negative number that it is below average. Most people have a Z-score between −2 and +2.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Nn.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brask-Lindemann, D., Cadarette, S.M., Eskildsen, P. et al. Osteoporosis pharmacotherapy following bone densitometry: importance of patient beliefs and understanding of DXA results. Osteoporos Int 22, 1493–1501 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1365-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1365-4